3.2

Rievaulx and the Order of St Benedict

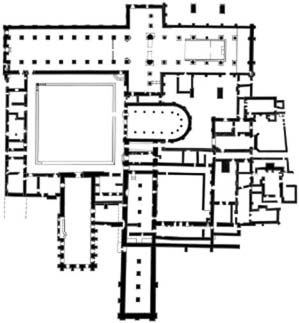

Figure 3.2.1 Basic layout of Rievaulx Abbey: A: church; B: cloister; C: refectory; D: chapter house

Source: After a published plan by English Heritage

Rievaulx abbey was a Cistercian foundation in Yorkshire dating from around 1150–1200 and reduced to a ruin at the dissolution.1 Enough remains though to exemplify a type that developed over a thousand years and later gave rise to the university and the hospital. The famous, accidentally preserved plan of the monastery of St Gall, dating from around 800, confirms in detail that the spatial arrangements had largely been determined by that period, but, of the earlier monasteries, including Benedict’s own of around 500, we know little.2 Rievaulx’s plan (Figure 3.2.1) develops around the cloister, a perfect square, architecturally celebrated, which is at once garden, space of contemplation and circulation (on cloister, see also Chapter 1.2). It is a clear evocation of the central principle, for around it all peripheral elements accrue. It is no accident that the cloister’s main hierarchically important axes, to east and south, are given to the chapter house as political centre and the refectory as social centre, chapter house taking precedence by sharing the church’s eastward orientation. The church, lying to the north of the cloister, is a clear exemplification of the linear principle, progressing from profane west door, via screens and steps, to the choir and holy altar, site of precious relics, with, beyond, the rising sun and risen Christ. The monks in the choir are separated from the nave and laity and split between the sides, so that they can sing antiphonally. St Benedict repeatedly refers to the antiphon in his correct order of observances, but, in his account, they happen in the oratory, the monks’ chapel, from which the monastic church developed. The sleeping quarters of the monks take the east wing of the cloister at first-floor level, stairs descending to its south-east corner, from which they could process to the church for the given hours of worship.

The Rule of St Benedict

The following extracts from Abbott Parry’s translation are presented in the given order of the chapters.3 They are chosen for revealing something of the assumed space of the monastery. We read, for example, of the oratory, where they pray, and which is the site of admission to the order, but is to be used for nothing else; of the dorter, where they sleep in single beds; of the library for books distributed in Lent; of the refectory, where they eat in strict silence; and of the kitchen, where the food is prepared. All these spaces appear in due order in relation to the regulated activities they serve. A need to assemble the whole community in making decisions is also stated, though not assigned a named room. The boundaries of the community are indicated by the range of places a monk might be found, by the treatment of guests, by the need for a wise doorman, and by punishment of wrongdoers, first by excommunication from prayer and meals, and ultimately by exclusion from the community.

Of political decisions

Whenever anything important has to be done in the monastery the Abbott must assemble the whole community and explain what is under consideration. When he had heard the counsel of the brethren, he should give it consideration and then take what seems to him the best course. The reason why we say that all should be called to council is this: it is often to a younger brother that the Lord reveals the best course.

(Parry 1990, Ch. III, p. 15)

Of the monk’s demeanour and territory

The twelfth step of humility is not only that a monk should be humble of heart, but also that in his appearance his humility should be apparent to those who see him. That is to say: whether he is at the work of God, in the oratory, in the monastery, in the garden, on the road, in the field or anywhere else, whether sitting, walking or standing, he should always have his head bowed, his eyes fixed on the ground, and should at every moment be considering his guilt for his sins and thinking that he is even now being presented for the dread judgement.

(Parry 1990, Ch. VII, p. 29)

Of the order of service to God

On Sundays . . . when the six psalms and the versicle have been chanted . . . and all are seated in due order in their stalls, four readings should be read from the book with their responsories, and the Glory is to be chanted only with the fourth responsory. When it begins all should arise with reverence. After these readings another six psalms should follow in order with antiphons and a versicle. After these again four more lessons should be read with responsories.

(Parry 1990, Ch. XI, p. 33)

Of the dormitory arrangements

The brethren are to sleep each in a single bed. These beds are assigned to them in order according to the length of their monastic life, subject to the Abbott’s discretion. If it is possible all should sleep in one place, but if their numbers do not permit this, they should take their rest by tens or twenties with the seniors who are entrusted with their care. A candle should burn continuously in the room until morning. They should sleep clothed . . . always ready, so when the signal is given, they should get up without delay and make haste to arrive first for the work of God, but in a gentle and orderly way.

(Parry 1990, Ch. XXII, p. 45)

Of the penalty of excommunication

Disciplinary measures should be proportionate to the nature of the fault, and the nature of faults is for the Abbott to judge. If then a brother is found to commit less serious faults he is to be deprived of sharing in the common meal . . . he may not intone antiphon or psalm in the oratory, nor may he read a lesson until he has made satisfaction. He must eat alone after the meal of the brethren.

(Parry 1990, Ch. XXIV, p. 47)

Of work in the kitchen

The brethren should serve one another, and no one should be excused from kitchen duty except for sickness or because he is more usefully engaged elsewhere . . . The one who is finishing his week’s duty does the washing on the Saturday; he should also wash the towells with which the brethren dry their hands and feet. Moreover, he who is ending his week’s service together with him who is about to start should wash the feet of all. The outgoing server must restore the crockery he has made use of, washed and intact to the cellarer, and the cellarer must hand it over to the newcomer, so that he knows what he is giving out and what he is getting back . . . On Sundays, immediately after Lauds, the incoming and outgoing servers should prostrate themselves at the feet of all the brethren in the oratory and be prayed for.

(Parry 1990, Ch. XXXV, pp. 62–3)

Of the readings at meals

At the meals of the brethren there should always be reading, but not by anyone who happens to take up the book. There shall be a reader for the whole week, and he is to begin on Sunday. Let him begin after Mass and Communion by asking the prayers of all that God may keep from him the spirit of vanity. The reader himself is to intone the verse, ‘O Lord open my lips, and my mouth shall proclaim thy praise’, and it is to be said three times by all. And so, having received a blessing, let him begin to read. There is to be complete silence, so that no whisper nor any voice other than that of the reader be heard there. Whatever is wanted for eating and drinking the brethren should pass to one another, so that no one need ask for anything.

(Parry 1990, Ch. XXXVIII, p. 66)

Of lateness in arrival

If at the Night Office anyone arrives after the ‘Glory be’ of Psalm 94, which for this reason we wish to be said altogether slowly and deliberately, he must not stand in his place in the choir but last of all, or in a place set apart by the Abbott for such careless persons, so that they may be seen by the Abbott and by everyone else, until at the end of the Work of God he does penance by public satisfaction. We have thought it best that such persons should stand last or else apart, so that being shamed because they are noticed by everybody, they may for this motive mend their ways. For if they stay outside the oratory, there may be someone who will go back and go to sleep again.

(Parry 1990, Ch. XLIII, p. 71)

Of reading books in Lent

In Lent the hours for reading are from the morning until the end of the third hour . . . and during these days everyone should receive a book from the library, which he should read through from the beginning. These books are to be given out at the beginning of Lent. It is important that one or two seniors should be appointed to go round the monastery during the hours when the brethren are engaged in reading, to see whether perchance they come upon some lazy brother who is engaged in doing nothing or in chatter, and is not intent upon his book.

(Parry 1990, Ch. XLVIII, p. 78)

Of the oratory

The oratory should correspond to its name, and not be used for any other purpose, nor to store things. When the Work of God has been completed all are to go out noiselessly, and let reverence for God reign there, so that if a brother should have a mind to pray by himself, he will not be disturbed by the ill-conduct of anyone else.

(Parry 1990, Ch. LII, p. 82)

Of the treatment of guests

All who arrive as guests are to be welcomed like Christ . . . The respect due to their station is to be shown to all . . . As soon as a guest is announced he should be met by the superior or by brethren with every expression of charity, and first of all they should pray together, and then greet one another with the kiss of peace . . . When they have been welcomed they should be led to prayer, and then either the superior or someone delegated by him should sit with them. The Divine Law should be read to them for their edification, and after this every kindness should be shown to them . . . The Abbott should give all the guests water to wash their hands, and with the whole community he should wash their feet.

(Parry 1990, Ch. LIII, p. 83)

Of admission to the order

The one who is to be accepted into the community must promise in the oratory, in the presence of all, stability, conversion for life, and obedience . . . he must write a petition, calling on the names of the saints whose relics are there . . . and he should place it with his own hand on the altar . . . If he has any possessions, he must either previously give them to the poor, or by means of formal donation give them to the monastery, keeping for himself nothing at all . . . At once then in the oratory, let him be stripped of his own clothes which he is wearing, and reclothed in those of the monastery. The clothes, however, which have been taken from him must be placed in the wardrobe, and kept there, so that if at some later time he should agree to the suggestion of the devil that he should leave the monastery, he can be stripped of the clothing of the monastery before being sent away.

(Parry 1990, Ch. LVIII, pp. 94–5)

Of the doorkeeper

At the gate of the monastery, a wise old man is to be posted, one capable of receiving a message and giving a reply, and whose maturity gurarantees that he will not wander round. The doorkeeper should have a cell near the gate, so that persons who arrive may always find someone at hand to give them a reply. As soon as anyone knocks, or a poor man calls out, he should answer ‘Thanks be to God’ or ‘God bless you’. Then with all the gentleness that comes from the fear of God, he should speedily and with the warmth of charity attend to the enquirer.

(Parry 1990, Ch. LXVI, p. 107)

Notes

1 See Pevsner 1966, pp. 299–307, Waites 1997, Fergusson and Harrison, 1999, and, more generally on monasteries, Braunfels 1980.

2 Walter Horn and Ernest Born made an extensive study of the plan of St Gall and constructed a model (Horn and Born 1979). St Benedict is reported to have written his rule at a monastery he developed in Monte Cassino, southern Italy; see Parry 1990, p. viii. A monastery is still there, but it has been rebuilt several times.

3 The Rule of St Benedict, translated by Abbott Parry and with an introduction and commentary by Esther de Waal, Gracewing, Leominster, 1990 (hereafter Parry 1990).