Sharjah, UAE

On land and in the sea, our forefathers lived and survived in this environment. They were able to do so because they recognized the need to conserve it, to take from it only what they needed to live, and to preserve it for succeeding generations.1

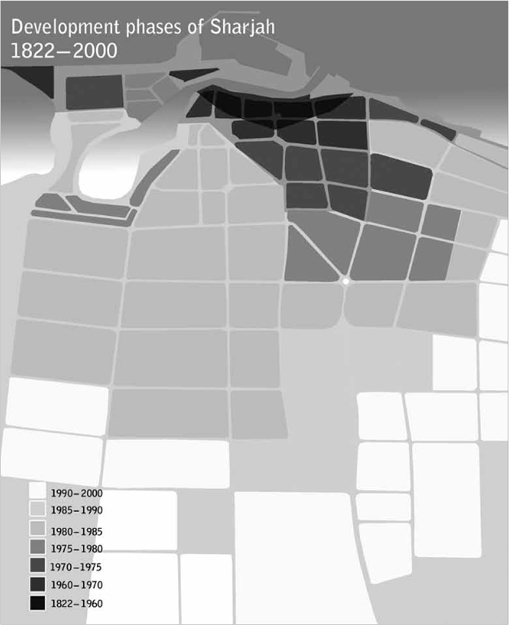

The city state of Sharjah is the result of a complex interaction of environmental, economic, political, and cultural factors across successive periods of time which shaped its particular physical form and social composition. Decisions made in response to multiple fast-changing economic and political pressures have greatly affected the urban planning of Sharjah – the most prominent of these factors being economic boom and the related population growth.2

Before the discovery of oil in the 1950s, Sharjah was under the protection of the British Empire. At that point there were only approximately 1,000 people living along the coastline in what is currently known as the ‘heritage area’. Economic resources were limited, and so local people were mainly dependent on fishing, pearl diving and sea trading. The British rulers produced a typical outline plan for Sharjah, around its creek, which still forms the basis for the city today. However, if one looks closely at the current formation of Sharjah, one can see that the city has been built without sufficient regulation or sense of urban planning. Due to the availability of land and the relatively low population in past eras, Sharjah was not yet being challenged – as it is today – by problems such as urban sprawl, traffic jams, lack of parking spaces, and an increasingly dysfunctional urban infrastructure.

In the 1960s, once oil extraction had got well underway, the new-found economic prosperity of Sharjah allowed rapid urban change. Oil became the single major source of income for the country. The introduction of modern technology that accompanied oil drilling, along with the advent of extensive trading exchange with the rest of the world, made the means of modern life available to the city’s citizens. Sharjah became one of the cities in the Middle East most eager to follow the western model of modernization and urban development. As a consequence, its environment was transformed to accord with the new local ambition to modernize the city as quickly as possible. A foreign workforce was invited to participate in the country’s urban development process. Indeed, continuous economic prosperity and the resulting demand for labour soon attracted a large number of non-Emiratis to come to work in Sharjah. This led to a dramatic growth in population: there are now an estimated 890,000 people in Sharjah’s metropolitan area, the result of which the ratio has in recent years reached around 20 per cent citizens to 80 per cent foreigners, like in neighbouring Dubai. The population increase has also caused daunting problems with spectacular consequences for the urban planning, not least in terms of the serious disruption of Sharjah’s surviving historical fabric.

THE CONSERVATION AND ADAPTATION OF OLD SHARJAH

From 1720 or so, the powerful Qawassim tribe first came to settle along the most strategic Gulf coastline from Ras Al-Khaimah further north down to Sharjah. Later on, in 1820, a general treaty signed with the British imperial forces caused the collapse of Qawassim maritime activity and divided the kingdom up into smaller sheikhdoms. Internal conflicts between members resulted in independence for Sharjah and Ras Al-Khayma as separate emirates by 1914. It is notable that the Qawassim tribe made Sharjah their urban hub, and it was there that the initial settlers survived through fishing, pearl diving and sea trading. Sharjah became in time a typical Arabic and Islamic walled town. Although its urban pattern shows some localized influences, it was the broader ideals and forms of an Islamic city which were predominant. An early map of Sharjah drawn by the British military in 1820 revealed that – while still obviously a small town – it already possessed several important features of a Islamic city that included:

• Al-Sour (defensive city fence/wall): Sharjah’s sour (1804–1819) was built by Sheikh Sultan I bin Saqr Al-Qasimi to protect it from invaders. The sour was constructed out of local materials such as stone reefs and sandstone brought in from the coastline and Abu Musa Island. This defensive wall was around 2.75 m high and 0.5 m thick. It had three main entrances through which Bedouins could enter the city with their camels and goats to sell them in the Al-Arsa market. By 1886, however, there were no parts of the sour remaining due to the expansion of the town.

• Palmary area: this was located outside the sour next to the water supplies.

• Al-Layyeh area: this was a small fishing village located to the south on the other side of the creek from Sharjah.

• Al-Jubail area: this was located outside the sour and had an elevated cemetery at 10–15 m above sea level.

• Coastal souk: this market was located along the coastline of the creek but within the sour, and it sold fish, gold and various different goods.

Surviving evidence from Sharjah’s early development shows that the city consisted of several types of architectural and urban elements. The most notable houses had clear Persian and Indian influences, and in general the built fabric was of a somewhat ‘primitive’ nature, called ‘arish. The Islamic community was established in several dense residential neighbourhoods. However, the slow growth of Sharjah during the 19th century – a period of decisive internal changes and important external influences – did not enable the city to reach the degree of urban maturity that was the case in other Islamic capitals. It was for this reason that the still-nascent Sharjah found itself unable to resist the pressures of modernizing change that impacted from the beginning of the 20th century (see Plate 16).

10.1 Development phases of Sharjah, UAE, from 1822–2000, showing the gradual move inland from the old port (top centre of map)

Hence, in 1930, Sharjah witnessed the birth of its first airport, immediately altering its urban morphology from the traditional to the modern. The airport was constructed by British military forces as a key transit point on the route between India and the United Kingdom. It brought in new financial income to the city at a time when its pearl trading was declining, and led to the need to form a new gate into the old town, connected by land and sea. This significant piece transport infrastructure underlined Sharjah’s strategic geographical position as well as introducing new patterns of technology and urbanism. The airport was created as a small military urban district containing more than 1,200 air-conditioned housing units, water reservoirs, power station and hospital, all protected by an encircling wall. The construction of the military airport and accompanying district influenced the whole traditional setting of Sharjah through the arrival of major new roads (albeit originally as dirt tracks). What is now Al-Uruba Road, currently used by trucks and lorries, was in fact the first landing strip. In 1938, the process of modernizing Sharjah’s infrastructure was given a further financial boost when the local government handed out contracts for British oil companies to explore the area for oil reserves.

THE RECTILINEAR AND THE GRID-IRON

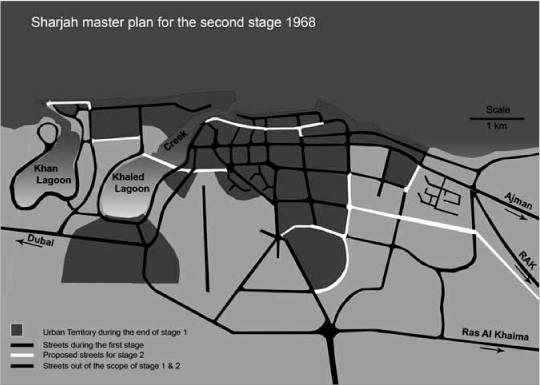

In 1968, just when the British military forces were preparing to leave the United Arab Emirates after 150 years of protectorate status, Sharjah had expanded in size to include new districts such as Maysaloon, Al-Falaj, Al-Sharq and Al-Mujarrah. It was therefore decided to draw up a plan that divided Sharjah into a more orderly, western-style grid. This master-plan was devised by the British civil engineering firm of Sir William Halcrow & Partners. From that point on, the city started to have even newer transport infrastructure such as metalled roads, roundabouts and a bridge connecting the old city to Al-Layyeh on the other side of the creek. In addition, with the creek now starting to dry up because of soil deposition, Sharjah’s urban form shifted significantly from a localized model to the modern urban archetype. The trend towards a rectilinear, grid-iron layout was stressed by the 1968 master-plan, and had impacted on the ground by 1980. The traditional old town was now stretched out to espouse the linearity of an ordered, westernised urban pattern. Consequently, the historic hub of Sharjah was confined to a series of heritage spots on the map.

10.2 First master-plan for Sharjah as devised by the British firm of Halcrow & Partners in 1968

The emerging grid-iron plan showed the emphasis now being placed on connecting roads at the expense of well-defined neighbourhood zones. The master-plan gave priority to the main avenues shown in red for its first stage, then to other projected urban roads marked in yellow for its second stage; there were also various roads around or outside the periphery (as indicated in white), which were projected to be built during both the first and second stages. The extension of roads served to enlarge the body of the city, creating a more stretched urban territory. Sharjah’s old city began to shrink even more under the vehicular pressure of the new road-based infrastructure.

Following Sharjah’s independence in 1972, the municipality did not tamper with the emerging westernised urban layout. Instead, it continued to lay out streets and divide the city into districts following the demands of road traffic. New green areas like Al-Zahraa Square were formed. Sharjah’s local government also decided to alter the entrance to and general shape of the creek, affecting the maritime commercial activities along the shoreline. By 1977, more houses were beginning to spread across the southern neighbourhoods and the first skyscrapers appeared in Sharjah. The city started to change to an even more modern form of rectangular urban blocks, metalled roads, roundabouts, green squares and landmark buildings (such as schools, hospitals, fire stations, etc). Sharjah now consisted of a series of eclectic urban parts set within a rigid traffic infrastructure.

THE SUBURBAN AND PERIPHERAL

The next key trend – towards suburban and peripheral development – was triggered by a new master-plan in 1980 that imposed an even more absolutist traffic map onto the city. Although the city was clearly not fully developed, the new plan allowed the spread of construction in peripheral areas where future roads were projected. And since the early-1980s, this trend has generated a sort of ‘urban suburbia’ which has heavily impacted on the relevance of having a city centre – or indeed the old core of Sharjah at all – as a point of reference.

10.3 Second master-plan for Sharjah drawn up in 1980 for implementation up to 2000

In the 1980 master-plan, Sharjah’s historic centre became totally subdivided within the overall traffic grid system, and the function of this zone was envisaged as being completely commercial. No regard was paid to the city’s heritage or to its role as a cultural focus; hence there are now only a very few civic and public buildings in the old quarter, not at all sufficient for such a large city. Similarly, the industrial district of Sharjah, which was supposed to be kept on the urban periphery, was now allocated a strategic area adjacent to the lagoons, and as a result the industrial zone ‘invaded’ the body of the city in a longitudinal manner, running in a northwesterly/south-easterly direction.

10.4 Drawing showing the dramatic changes to just part of the old historic area of Sharjah by 2008

This second master-plan continued to be implemented up to the year 2000 without any rectification or without anyone really questioning its relevance. Although concerns about urban heritage had become a serious issue in the Arab region since 1975, through the actions of UNESCO and other heritage organizations, it appears that the authorities within Sharjah’s government were not yet equipped to review the city’s past in a constructive way. Only minor restoration works on some selected buildings were undertaken. On the other hand, the implementation of the master-plan was at full gear, which had a great impact on the current shape of the city. Historic Sharjah became a piecemeal collection of heritage spots with the main banking street crossing its main zone. Since 2000, newer traffic plans have been generated but again without any consideration of the continuous disorder being created in the heritage area. Moreover, despite the fact that the old city has always been very active, and still preserves some of its traditional social and commercial activities, urban policy still seems to focus on the historic theme-park aspect.

THE BIRTH OF A NEW CITY CENTRE IN SHARJAH

The call for a new, alternative city centre was prompted by this loss of purpose for the old town and the consequent absence of a civic dimension within the city. The establishment of the three lagoons as an attractive natural feature along Sharjah’s southerly coastline – with Al-Khan Lagoon and Al-Mamzar Lagoon now joining the adjacent Khalid Lagoon, the latter being an extension of the old creek – as well as competition from Dubai’s well-known tourist and entertainment resources, has created the need for a new urban magnet. Currently, the area around the lagoons is becoming noticeable for high-rise buildings and continuous efforts to design the landscape to create a simile of Dubai. However, this new city centre cannot fully replace the cultural meaning of the historic hub of Sharjah.

Indeed, the disconnected old and new centres in Sharjah generate an urban antagonism. On one hand, the active traditional harbour is still a vibrant seafront with partial heritage remnants occupied by dynamic, multi-ethnic commercial activities. On the other hand, the more artificial aquatic vision of the lagoons represents the contemporary image of Sharjah with its mixed functions. This antagonism ought to be resolved either by merging the two centres into one large whole, or else carefully creating a bi-polar central area for Sharjah that balances its historical and contemporary urban images.

The area around the lagoons is currently driven by a competitive and somewhat random market-led development process, and no master-plan has been set up to face the dilemma of ensuring infrastructural, cultural, and environmental sustainability. The Al Qasba district between Khalid Lagoon and Al-Khan Lagoon is the only macro-project that reflects a clear vision, in terms of a cultural and environmental package, which is worthy of consideration amidst chaotically dispersed government and private buildings. Therefore, the new transportation plan is again an a posteriori resolution of urban issues and problems, and is not based on a holistic vision for the future planning of Sharjah. What is needed instead is for us to trace the urban changes in Sharjah to understand its inner strengths and weaknesses within a wider professional lens.

ENVIRONMENT AND WATER IN SHARJAH

Sharjah’s history is woven around its main waterfront, and this now includes two of the large artificial lagoons, Khalid and Al-Khan, with the Al-Qasbaa Canal linking them. Hence in order to gain a deeper understanding of the urban fabric and environmental pressures in Sharjah, it is crucial to look at the present status quo of its water infrastructure and the waste-water crisis which is now constraining its proper development.

Khalid Lagoon has become one of the most important features of the city and key to its socio-economic status. It is a fair size, with its surface area is about 3,000,000 m2, but with a depth of only 3–7 m. Khalid Lagoon is located right in the heart of the city and is surrounded by high-rise buildings, markets, recreational parks, entertainment and cultural centres, and busy commercial districts. The area around the lagoon is widely used by Sharjah residents for recreation and socializing, while the lagoon itself is used for boating, water sports and commercial activity. The lagoon is connected to the Gulf by the narrow channel of the creek, known as Al-Khour, and this is how water is exchanged. The creek is heavily used by ships and boats, and the surrounding land use is predominantly commercial.

Similarly to Khalid Lagoon, the nearby Al-Khan Lagoon is also connected to the Gulf through a narrow channel. Al-Khan Lagoon is used mainly for recreational fishing and boating, and the district is less developed than the area around Khalid Lagoon, although development is increasing rapidly. The Al-Khan Lagoon is easily the smaller of the two main lagoons, with a total surface area of approximately 1,500,000 m2 and a depth of between 5–7 m. In addition to realising the social and economic benefits of creating the lagoons, the Sharjah government has also invested in constructing the Al-Qasbaa Canal between them in part to help improve the water flow and consequently improve the water quality. First commissioned on 8th November 2000, the canal is now about 1 km long, 5 m deep and just 30 metres wide. A gate is provided at the Khalid Lagoon end of the canal to allow water to flow in one direction from Al-Khan Lagoon into the Khalid Lagoon, but not in the opposite direction.

Despite such improvements, the shortage of water supply and poor waste-water management, which is still overly reliant on septic tank systems, are major issues in Sharjah. Without immediate municipal legislation, and a clear strategy for water provision and management, the city faces tremendous environmental challenges to its rapid urbanization. The steady growth in population, high-rise buildings, industrial zones, tourist activities and public facilities has increased exponentially the usage of both drinking and sewer water. This heavy usage is not being managed properly, challenging the urban authorities to be able to cope with rapidly rising demand for all kinds of water supplies.

URBAN PLANNING AND GOVERNANCE IN CONTEMPORARY SHARJAH

The history of planning in Sharjah has been related mainly to the grid pattern – the main focus for which was the automobile per se. The first master-plan for Sharjah in 1968 set out a traffic engineering schemata that impacted on the city’s and has only created chaos and disorder up till now. Although Halcrow & Partners claimed at the time to be pioneering the future growth of Sharjah, facts on the ground proved that their plan was mediocre vis-à-vis what was being achieved internationally in terms of urban planning. Since the emergence in 1968 of the main road, which stretches from the southern border with Dubai to Ras Al-Khaimah to the north, Sharjah has gone through a number of major urban and geographical transformations based on infrastructural demands: these include Corniche Road along the creek, Port Khalid, and now the three artificial lagoons.

In addition to the unsuccessful master-plan by Halcrow & Partners, the city suffered acutely from not having a sufficiently qualified institutional structure to execute planning policy and follow up with requisite guidelines. As in most Arabic and Islamic countries, the first local municipalities imported by colonialists were rather useless and clashed with traditional systems of social management (Hisba, Qadha’, guilds, etc.). These municipalities needed time to develop and mature in tandem with the complex nature of contemporary Islamic cities. However, in most cases it is sad to say they are still not fully competent to run the planning and management of their urban spaces.

10.5 Traditional and modern architecture together in Sharjah

This clash between the older and newer styles of city management has resulted in the destruction of old Sharjah, the potential of which does not seem to have been perceived – or, rather, was ignored. Local heritage tended to be regarded as ‘primitive’ and thus unsuitable for a modern ‘developed’ city. Therefore, major destruction was undertaken to insert new boulevards into the body of the old town. No real effort was made towards conservation and no concern was shown as to the value of cultural resources. While progressive urbanism worldwide was questioning the validity of centralized planning and the imposition of city forms and concepts onto inhabitants, the international consulting offices were simply having their day in a region where criticism is scarce and a fascination with modern westernised forms blinded all stakeholders involved in the process.

To counter the destructive process of the historical memory and heritage of Sharjah, His Highness Sheikh Sultan – with the foresight of a cultural renaissance – initiated a long-term restoration programme that has thankfully saved the most strategic part of the city from eradication. However, this restoration work is clearly not enough today to meet the planning pressures on the whole city. The sheikh’s office is keen to undertake this task, believing that sound planning is required to underscore the value of built heritage in the future Sharjah as a cultural anchor within the UAE. For this reason, Peter Jackson, a architect interested in cultural heritage, was hired since 2007 as the Sheikh’s office advisor in order to oversee the planning process.

10.6 New office towers in downtown Sharjah

As such, this revived planning process needs to take into consideration the following aspects:

• Integration: heritage sites and monuments should be an integral part of planning policy.

• Continuity: the need is to establish a new master-plan that can guarantee the historical and cultural continuity of Sharjah.

• Diversity: heritage preservation means not a partial approach, but a holistic one that considers all past or present cultural differences.

• Identity: the planning process should protect the sense of identity and sense of belonging to Sharjah, while also being cosmopolitan and modern.

• Profit: cultural investment must not be about making the city into an absolute museum, but instead needs to rejuvenate Sharjah’s history so it remains a sustainable centre of commerce and trade.

• Development: the planning process has to preserve the existing heritage and increase resources to produce new cultural experiences and thus valuable heritage for the future.

• Community: heritage sustains communities and forges their memories of place, meaning that heritage planning empowers a community to define itself, creating greater social and cultural attachment to its living space.

• Environment: heritage has also to include natural and ecological resources that augment the experience of architectural and urban heritage, and sustaining environment would enable Sharjah to balance its modern development while preserving its ecological dimension.

• Density: the fast-growing population in Sharjah has to be managed to avoid the social chaos found in other Arab cities. For any city to prosper, its planning strategies ought to remain within the capacity to retain a reasonable density and maintain the quality of civic life.

• Traffic: this should be merely a means, and not an end in itself as it is today in planning. Sharjah should not be a transit route through its central zone, but instead should remove all disturbing vehicular influxes to outside its urban territory so that inhabitants and visitors alike can better appreciate its history and cultural resources.

In order to reach these planning goals, Sharjah cannot rely on its current human and technical resources since there are not at the level expected for such an optimistic endeavour. The city’s planning authorities are sub-standard, and rampant real-estate development is likewise hindering the planning process. In absence of a clear planning governance and sufficient local technical expertise, the planning authorities are not being challenged enough. Therefore, constructive criticism is usually seen more as a threat rather than something that can help to shape a better future for Sharjah.

CONCLUSION

Rapid economic and population growth in Sharjah has led to a number of unintended consequences. The last master-plan from 1980, which set out a pattern of infrastructure to create urban zones and other features, is not really applicable any more, nor is it guided by clear urban legislation. This lack of sound urban zoning is clearly constraining the city from becoming a functional urban agglomeration, leading to poor accessibility, weak public facilities, unclear urban boundaries, excessive mixed-use areas, and housing sprawl. Traffic flow and parking problems are major urban issues because of the improper planning of transportation circulation networks which are undergoing continuous reformulation and change.

In terms of built-up areas in Sharjah, there is generally a lack of strict rules and regulations in how the land market is operating. It means that the city has reactively grown to follow the demographic increase but has been designed as a series of disconnected parts (at the architectural level) and not as a whole (the urban level). The unidirectional urban extension of Sharjah because of confining boundaries with Dubai, Ajman and the Gulf coastline is placing real pressure on the city centre to grow up vertically through an increase in high-rise buildings. However, these new towers are the result of land speculation without the adequate urban infrastructure appropriate to such building types. Meanwhile, the cultural heritage area in old Sharjah is coming under threat of disappearing altogether from the map of the city, despite the continuous efforts to preserve some the scattered remaining historic buildings.

In addition, due to the critical urban status quo, the city is spending a colossal municipal budget just to survive, and there is no adequate planning system to envision tasks and tailor expenditure accordingly. Foreign private consulting companies are still in control, just as they were in the days of the British protectorate, and are not willing to empower the municipal planning authorities or to enhance the skills of civic employees. If one wants, for instance, to conduct a study into the current urban crisis of Sharjah, one finds that most government documents are in fact in the custody of foreign companies, which is also very risky as these companies may leave at any time without prior notice. Hence, for a proper planning process to be established, the following measures are vital:

• Development of municipal leadership and administrative capacities.

• Building up a sound database about Sharjah (such as data on socioeconomics, geography, heritage resources, traffic patterns, etc.).

• Establishment of better institutional communication and negotiation.

• Closer management of stakeholders and decision makers.

• Development of sufficiently qualified local professionals.

• Stronger management of private buildings projects in the city.

• Establishment of a sound urban legislation.

• Encouragement of public participation in the planning process.

NOTES

1 As quoted in UAE Ministry of Information and Culture, United Arab Emirates Yearbook 2002 (London: Trident Press, 2002), p. 19.

2 The account in this chapter is based on the following sources: Nasser H. Abbudi, Safahat min Athar wa-Turath Dawlat al-Imarat al-Arabia al-Muttahida (Ain: Zaid Center for Heritage and History, 2002); Hind Al Yousef, ‘A Green Legacy’, 20 September 2008, Gulf News website, http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/uae/environment/a-green-legacy-1.132208 (accessed 5 October 2009); Graham Anderson, ‘The Issue of Conservation of Historic Buildings in the Urban Areas in the Emirate of Sharjah’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Durham, UK, 1991); Jan Assmann & John Czaplicka, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural Identity’, New German Critique, no. 65 (Spring 1995): 125–133; Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage Books, 1961/92); Mohamed Mursi Abdullah, Dawlat al-Imarat al-Arabia al-Muttahida Wajiranuha (Kuwait: Dar al-Qalam, 1981); Christian Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci (New York: Rizzoli, 1980); John J. Nowell, ‘Now and Then: The Emirates’, Arabian Historical Series (Vol. 1, Dubai: Gulf Printing & Publishing, 1998); Abdullah A. Rahmah, Al-Imarat fi Dhakirati Abna-iha: al-Hayat al-Iqtisadia (Sharjah: Manshurat Ittihad Kuttab wa-Udabae al-Imarat, 2005); Ali M. Rashid, Al-Hussun wal-Qila’ fi Dawlat al-Imarat al-Arabia al-Mutthida (Abu Dhabi: Isdarat al-Mujamma a-Thaqafi, 2004); Mohamed Shakir, Mawsu’at Tarikh al-Khalij al-Arabi (Amman: Dar Usama li-Nashr wa-Tawzi, 2003); ‘Sharjah, promoting the culture of understanding’, New York Times Magazine (special advertising supplement produced and sponsored by Summit Communications), 13 May 2007; Salim Zabbal, Kuntu Shahidaa: al-Imarat min 1960 ila 1970 (Abu Dhabi: Isdarat al-Mujamma’ Thaqafi, 2001).