Shopping Malls in Dubai

While Dubai’s mercantile origins occupy a longer timeline and different physical landscape to today’s modern metropolis, this essay focuses on the compressed historical-spatial dialectic that has imprinted Dubai within the collective global consciousness. Chronologically, the infrastructural initiatives which first established modern Dubai’s trajectory1 were broadly coincident with the rumblings of dissatisfaction that beset the modernist movement in the early-1960s, most notably voiced in Jane Jacobs’ great polemic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Of most significance here was Jacobs fascination with the processes and structural configuration that are necessary to sustain a vital urbanity, as observed within her native New York, and especially in Greenwich Village, contrasted against deterministic principles of the regimented visual order in modernist town planning that – in her brutal analysis – assumed the ‘dishonest mask of pretended order, achieved by ignoring or suppressing the real order that is struggling to exist and to be served.’2

Dubai is of course a long way from New York, and the extent to which its large-scale urban grain differs from the focus on more intricate patterns of city life advocated by Jacobs is immediately noticeable. Dubai has flourished precisely by employing the characteristics that Jacobs believed a successful urban realm should avoid at all costs. On deeper reflection, this may not be such a surprise. Jacobs’ analysis observed a condition where there was an established cityscape and a relatively mild climate, suitable for an active life on the city street all the year round. Dubai, conversely, sits in the desert with temperatures almost twice those of New York (or its European counterparts) at any given time of the year, and yet has grown from a sleepy regional port to an internationally recognized metropolis in less than fifty years. The adoption of that most American, albeit principally suburban, building type – the shopping mall – as the means of delivering urban space in modern Dubai exemplifies the awkward gap between the theory and practical reality of what a city might be under such circumstances. It is a scenario that clearly perplexes urban theorists in Jacobs’ shadow, who recite declamations of a soulless and weak urbanity dominated only by vulgar consumption. Instead, I would argue, these types of statement indicate a reading of the city that – despite its relevance to a Euro/American context – may have reached its limits within an environment whose compressed history and climactic challenges ask a wholly different set of questions of what a city should be. Through an analysis of the shopping mall as a building typology that is hybridized in this extreme context, this chapter will explore its relevance to the making of modern Dubai and the nature of the urban space that results. But first, we must qualify the relevance of the building typology within this context a little further.

Dubai’s assumed ‘status as the lower Gulf’s economic capital’3 – born out of its free-trade orientated infrastructural gambles, namely through the expansion of Port Rashid4 and later the opening of Port Jebel Ali5 – is one that is now proving difficult to sustain. Itself relatively impoverished in terms of ownership of the Middle East’s most precious natural resource, oil, yet part of a country, the UAE, which holds the world’s sixth largest reserve,6 Dubai lives in the constant shadow of its neighbouring Emirate, Abu Dhabi, which controls 90 per cent of this resource.7 Without the self-sustaining financial security of its neighbour, Dubai’s ruling al-Maktoum family instead felt compelled to make a ‘commitment to invest in their own domestic infrastructure so that Dubai would be able to support and enhance its existing re-export and commercial sector while also facilitating broader diversification away from oil in the future.’8 It is striking to note that oil and natural gas account for less than 6 per cent of Dubai’s economic activity.9 Rather, it is speculative real estate/construction, trade/re-export, financial services and luxury tourism (attracting around 5 million visitors per year) that now dominate.10 Dubai’s financial security is thus dependant on an openness to foreign investment, necessitating that it adopts a commensurate ‘visibility’ to the outside world.

While this openness can easily be represented statistically – a staggering 80 per cent of the city’s population of 1.7 million consists of expatriates – it is even more explicit in the provenance of architectural forms that represent the modern city. Displayed here is the strategic intersection of capital and skyline commensurate with ‘the infrastructure and the servicing that produce a capability for global control’.11 However, it is hardly sufficient, within this global representation of place image, to reproduce the generic cityscape of elsewhere. Mike Davis observes that:

… the same phantasmagoric but generic Lego blocks, of course, can be found in dozens of aspiring cities these days (including Dubai’s envious neighbours, the wealthy oil oases of Doha and Bahrain), but al-Maktoum has a distinctive and inviolable criterion: everything must be ‘world class’ by which he means number one in the Guinness Book of Records. Thus Dubai is building the world’s largest theme-park, the biggest mall (and within it, the largest aquarium), the tallest building, the largest international airport, the biggest artificial island, the first sunken hotel, and so on … Having ‘learned from Las Vegas’, al-Maktoum understands that if Dubai wants to become the luxury-consumer paradise of the Middle East and South Asia (its officially defined ‘home market’ of 1.6 billion people), it must ceaselessly strive for visual and environmental excess.12

Captured within Davis’s description of the Dubai skyline are those characteristics that have pervasively displayed themselves as the stuff of globalised architecture since Jacobs’ polemic half a century ago. It is a process recognized by David Harvey as the ‘relation between capitalist development and the state … as mutually determining’.13 Ostensibly this describes a top-down vision whose autocratic underpinnings are obfuscated by a language of visual spectacle borne of, though far removed from, the core intent of Jacobs’ theories. The hegemony of global capital is reinforced by stealth, at the expense of the genuine existence of micro-level processes of urban interaction from which its supporting visual rhetoric is drawn. By superficially harnessing the streams of critical thought that served to undermine the socially progressive aspirations of the modernist project, capital has also hollowed them out, limiting the potency of any new influence that contemporary theory may attempt to produce.

At a global level, the shopping mall is a building typology that is central to this penetration of capital into all facets of modern life under the democratizing auspices of populism. Founded on the generic building block of a spatial formula that was christened the ‘dumbbell plan’ (the brainchild of the godfather of the shopping mall, Victor Gruen), and which persists due to its devastating financial success, the internalised environment of the mall differentiates itself within a given consumer market via a language of decorative surface that can be tailored to suit any target demographic.14 Asserting itself as a more desirable alternative to a given lifestyle, the mall, in its ‘native’ western existence, typically adopts the form of a pastoral alternative to the perceived ills of urbanity – in other words, a self-contained entity accessed by car and predicated on familial values of safety and togetherness. It is a scenario that Kim Dovey describes as ‘a collective dream world of mass culture … at once captur[ing] and invert[ing] the urban. It is a realm of relative shelter, safety, order and predictability which is semantically and structurally severed from the city.’15 Whether the city actually represents the threat implied by the mall, and whether the mall can deliver a genuine alternative to the collective anxiety that it fosters, remain highly questionable.16

Transposed to Dubai, however, this strategy of ideological opposition finds a more tangible target: the climate itself. A climactically controlled internal environment provides Dubai’s expatriate population and tourists, many of whom are totally unused to the fierce heat of the desert, with a comfortable public space that possesses a deeper significance than the inferred civic benefits within the mall’s western context. Rem Koolhaas, in his study of the urban spaces of Singapore, a context whose tropical climate in many ways echoes the challenge of Dubai, describes it thus:

… [It is] the city as a system of interconnected urban chambers. The climate, which traditionally limits street life, makes the interior the privileged domain for the urban encounter. Shopping in this idealized context is not just the status-driven compulsion it has become “here” but an amalgam of sometimes microscopic, infinitely varied functional constellations, in which each stall is a “functoid” of the overall programmatic mosaic that constitutes urban life.17

Onto this scenario, Dubai has even grafted one of its most prominent civic events, the Dubai Shopping Festival, which takes place during February each year in its shopping malls, attracting 3 million visitors to the city.18 While undoubtedly a commercially driven stimulation of tourist cash, it is also representative of the kind of spatiality in which much of the city’s social life takes place, and of the principal activities it offers.

Climatic necessity aside, the need to understand the civic space of the Dubai shopping mall is made even more vital by the less visible role that this typology plays in the general apparatus of globalization within a skyline contrived to attract foreign capital. The shopping mall can thus be understood as assuming, for the foreigners drawn to Dubai, a means by which the inhabitation of a largely alien context is naturalized through more familiar symbols and spatial practices. In mitigating the effects of cultural dislocation that are inherent in the expatriate lifestyle, the mall compresses geographical space as a ‘response to desire for fixity and for security of identity in the middle of all the movement and change. A ‘sense of place’, of rootedness, can provide … stability and a sense of unproblematical identity.’19

The implication is that in Dubai there is indeed a transcendence of the consumption-based values that undermine our perception of the western shopping mall, though key questions still remain – such as, what are the civic qualities of the urban space the Dubai mall actually produces, and to what extent are cultural processes also hybridized by the transplantation of the mall into this context?

Our search for answers to these questions begins as the grain of old historic Dubai bleeds into its modern skyline, stewarded from the early-1990s by its ruler, Sheikh Mohammad bin Rashid Al Maktoum. Located at the commencement of Sheikh Zayed Road (the long axis linking Dubai to Abu Dhabi), the Bur Juman Centre – unlike many structures that define the Emirate’s brand image – displays its own internal history. As one of Dubai’s very first shopping malls, opened in 1991 by the Al Ghurair Group, the centre was soon forced to compete with newer and far more sophisticated malls as expatriates, tourists, and their concomitant money flowed in.20 Accordingly, the Bur Juman Centre was given a face-lift and relaunched in 2005 as a high-end mall aimed at the luxury market. This six-yearlong, AE Dirham 1.4 billion expansion at the hands of an American architect, Eric Kuhne (who also designed the Bluewater mall in the UK) duly doubled the size of the centre to 80,000 m2 with 300 shops.

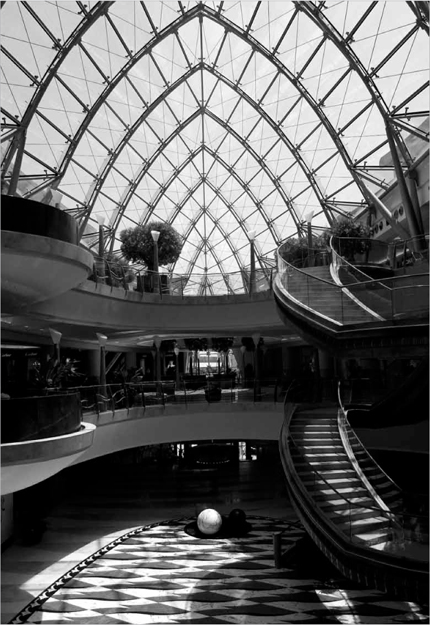

Kuhne believes his work has deeper significance than a straightforward rebranding exercise. Naming his design sphere as that of the ‘Civic Arts’, and referring to the project as Bur Juman Gardens, Kuhne clearly wishes to be perceived as a socially and contextually conscious architect, above the morass of commercial architecture in which the mall usually sits. In his own words, ‘Bur Juman Gardens celebrates the diversity of science, arts, and letters that the Arabic World has contributed to civilization’.21 Grand words indeed, but what does this vision really deliver? Kuhne’s extension avoids the outright pastiche of image and form that undermine so many shopping malls, instead favouring abstracted contextual motifs. These include a pseudo British High-Tech series of laminated timber beams and roof glazing whose references to the designs of Michael Hopkins et al. are robbed of any feeling of integrity by the overbearing sheen of marble and fussy decorative details adorning many of the mall’s internal surfaces. While a certain Arabian flavour in some of these details lends a localized reference over and above one’s conventional expectations of shopping mall interiors, the overall result is far from the didactic historical message that Kuhne’s rhetoric implies.

9.1 Atrium roof in Bur Juman Gardens

9.2 Modern extension to the Bur Juman Centre

9.3 Original mall at the Bur Juman Centre

The visual tension between the mall’s history and its need to suit Dubai’s contemporary brand image is particularly problematic. Spatially joined as a seamless figure-of-eight configuration, the visual contrast between the shiny new extension to the Bur Juman Centre and its first phase could not be greater. The resulting disjuncture only serves to reveal that it is the building’s underlying plan form which is the key determinant of its spatiality, a point which is worth exploring further. The notion of an instrumental plan as the basis of the shopping mall is not of course a new concept. Victor Gruen’s ‘dumbbell plan’ has, since the earliest days of the typology, exerted an almost unbreakable hegemony over the design process. Comprising a linear shopping route flanked by smaller retail outlets, and terminated at either end by large ‘anchor’ stores, this spatial formula understands that the ‘exposure of all individual stores to the maximum amount of foot traffic is the best assurance of high sales volume’.22 Functioning as shopping magnets, the two anchor stores draw consumers through the entire range of curiosities and temptations which the mall has to offer, heightening the user’s psychological stimulation to engage in acts of consumption. By coupling this pattern of coerced perpetual movement with its internalized plan form, the mall creates an introverted journey of consumption freed from the unplanned distractions and encounters which occur in more traditional urban scenarios. The atomization of the mall’s inhabitants forms the bedrock of the sustained consumption-led fantasy on which its financial success depends, though regrettably robs the typology of many of the interactive social processes that Gruen had hoped would be fostered within his creation.

As the scale of global mall developments grew, Victor Gruen’s generic formula has developed a number of variants to counteract the fatigue its instrumental axial layout can produce.23 More than most, Eric Kuhne has realized the importance of balancing the feeling of perpetual movement with manageable chunks of visual information as a subtle means to manipulate the formula. His figure-of-eight plan in the Bur Juman Centre stimulates an effortless, repetitive cycle of movement, different to the more rigid and mechanical qualities of its linear predecessors, plus it uses the curvature of the mall layout to break the consumer’s line of site – this becomes a means to divert their attention onto the immediate shopping environment, while the promise of yet further riches, just out of view, stimulates further exploration. While its plan form may thus have changed, it is clear that the coercive tools underpinning the Bur Juman mall are as strong as ever. Ignoring Kuhne’s rhetoric, it seems his real talent is to eke a little more life from this deadly equation between plan and profit in the shopping mall. In this sense he is a worthy successor to Gruen, even if the latter was not as aware of the Faustian pact he was making with this spatial formula when it first left his drawing board.

Unfortunately for Kuhne, the success of the mall’s spatial formula depends on concealing these manipulative processes beneath a totalizing, immersive surface language that brands the mall experience for its target demographic. The ‘authenticity’ of any surface language, however, is undermined by the aforementioned disjuncture between the old and new sections of the Bur Juman Centre. It is an architectural moment that reveals the mall’s ephemeral qualities all too clearly, asking some difficult questions of the pseudo-urbanity it seems to offer. Sitting as a symbolic marker at the point where the historical city breaks down to reveal the new Dubai 2.0, the defensive, large-scaled block of the Bur Juman mall neither integrates itself into the grain of the historic city, nor does it offer a credible alternative. Rather, the tired, bland appearance of the original Bur Juman is a depressing reminder of the compressed sense of time from which all malls suffer, and the willfully contradictory dialectic between form and function which are ever-present. The Bur Juman Centre may mark the start of Dubai’s new global journey, but is also a cautionary tale of the limits to which branded modernity, constantly required to re-invent itself on no substance at all, is subjected.

If we move onward in search of Dubai 2.0, the dimension of difference between the old and new urbanism becomes quickly apparent. While old Dubai clusters around the creek inlet that extends from Port Rashid, defined by the pedestrian-scaled nuclei of Deira and Bur Dubai, the new city stretches out as a 30-km strip either side of the 12-lane highway of Sheikh Zayed Road. The resulting urban structure is defined visually by a continuous procession of towers lining the edge of the road, falling behind, almost instantaneously, to a low-rise carpet of residential and luxury hotel buildings terminated on one side by the Persian Gulf and on the other by the desert. While it is the symbolic capital invested into the skyline that is meant to be seen, arguably more significant is the road itself. Following the coastline, the combination of linear road and surrounding desert ensure that the new Dubai is a long narrow affair (little more than 4 km wide). It’s a linearity rendered even more intense by the impassable barrier that the road itself presents, almost perfectly bisecting the strip development it creates. Moreover, the stretched out, car-oriented scenario explicitly abandons the relational pedestrian networks commonly associated with western conceptions of the ‘ideal’ city. In the new Dubai, the realm of the pedestrian becomes instead a series of nodes spread out along this immense strip and accessible only by car. These nodes have evolved beyond the fault line between history and modernity on which our western urban precedents precariously sit. With such values left behind, all too quickly, it is to Dubai’s image as a burgeoning globalized metropolis that our attention is directed: nowhere is this message encoded more strongly than in our next shopping mall for study.

Situated at the base of the world’s tallest structure, the 828 m-high Burj Khalifa Tower, which opened in January 2010, the Dubai Mall apes the lead of its totemic marker by asserting itself as ‘the largest shopping space in the world’.24 The title of the world’s largest shopping mall is something which is subject to much competition between emerging global economic hubs, all of whom are vying to outdo one another in the race to supersede the United States within the capitalist framework it defines and, at least for now, still spearheads. Accordingly, the means by which claimants to the title of biggest mall are measured are rather nebulous. In terms of total floor area for all facilities, the Dubai Mall is indeed the world’s largest at around 250,000 m2 – but if one were to look at the gross lettable area for shops to occupy, it in fact only sits in 7th place (with the top spot going to the New South China Mall in Dongguan, China).25 By any standards, however, the Dubai Mall is truly immense. Designed by the Singapore-based mall specialists, DP Architects PTE, the Dubai Mall comprises 1.2 million m2 of accommodation arranged over four levels, containing 1,200 shops and also an aquarium/underwater zoo, 2,000-person capacity ice rink, 22-screen multiplex cinema, 120 restaurants and cafes, and 14,000 car parking spaces. It attracts more than 750,000 visitors per week.26 While this barrage of statistical worthiness serves to infuse the craving for ‘world class’ symbolic capital evoked in the earlier quote from Mike Davis, its scale alludes toward a richer stream of social capital, which according to Rem Koolhaas, forces us to see that ‘in the quantity and complexity of the facilities it offers it is itself urban’.27 Echoing this, the Dubai Mall’s designers state that ‘it is sine qua non that the mall be conceived and planned as a microcosm of a metropolis, a City within a City, to ensure that the desired qualities of live [sic], work and play are perpetuated.’28 The question we must address is the nature of the physical structure on which this purported ‘city within a city’ is founded.

9.4 Main pedestrian concourse at the Dubai Mall

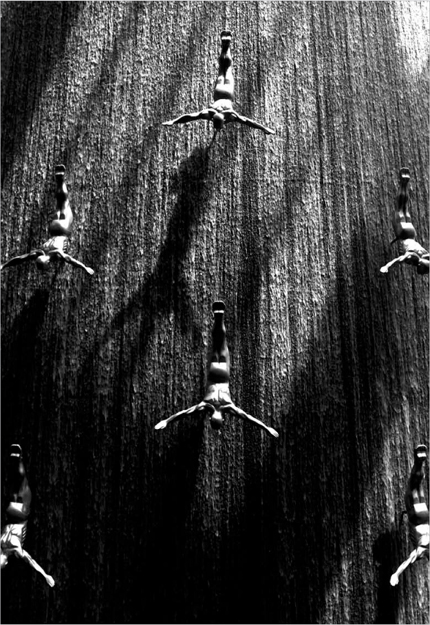

As in the Bur Juman Centre, the Dubai Mall eschews Gruen’s traditional ‘dumbbell plan’ in favour of a triangular layout with gently curving malls. The origin of this particular configuration comes from Erich Kuhne, Bur Juman’s designer, in his scheme for the Bluewater shopping centre, just outside London, from the late-1990s. Its Dubai offspring has simply super-sized the concept. In essence, ‘the arduous intermediate stages of commercial evolution have been telescoped or short-circuited to embrace the “perfected” synthesis of shopping, entertainment, and architectural spectacle on the most pharaonic scale.’29 Again, the triangular plan stimulates a sense perpetual movement, this time with three ‘anchors’ at the points, each signified by an event – here it is two large shops and, bafflingly, a public art installation. Consumers’ motion is broken only at carefully choreographed moments when one is able to interact with a man-made lake, through terraces connected to the mall’s many restaurants, and all within the colossal shadow of the Burj Khalifa Tower.

9.5 Public art installation in the Dubai Mall

So it might seem in the Dubai Mall that the globally-biased conjunction of plan and profit has prevailed yet again, and that there is perhaps never any other possible outcome. Such an assumption, however, assumes that the mall’s inhabitants are reduced to wholly passive bodies capable only of a rigid adherence to the social contract it wishes to define. But that would be an erroneous reading, since it ‘leads to an overestimation of the efficacy of disciplinary power and to an impoverished understanding of the individual which cannot account for experiences that fall outside the realm of the “docile” body.’30 It is thus imperative to acknowledge, and move beyond, the generic physical structure of these Dubai malls to discover the ‘relation of subject to discursive formations as an articulation’ which are inscribed within them, as part of a far more complex and interesting field of global/local tensions.31

Perhaps the most obvious trace of the culturally specific contestation of generic mall space, if one visits at the right time of year, is the change in the mall’s psychogeography during the month of Ramadan. To adhere to the pattern of daylight fasting, the mall must close its restaurant amenities until the sun goes down. In one sense, this represents a minor triumph of indigenous cultural practices over the relentless pursuit of profit by the global mall machine. It also temporarily shrinks the size of the mall’s ‘turf’, and in doing so reveals its programmatic limitations. At the Dubai Mall, the response is to excise its lower restaurant level during the daylight hours of Ramadan, effectively reducing the mall to a three-storey affair. Most interesting, however, is the way in which this scenario in the mall plays out the underlying tensions that exist between Dubai’s Muslim population (both local and expatriate) and the almost entirely expatriate non-Muslim diaspora. Some malls deliberately blur the boundary of their acknowledgement of Ramadan, and other cultural practices, through subtle manipulation: for instance, it has become common practice for many restaurants to obscure views in and out during daylight hours, to conceal the non-Muslims eating within. For this period, therefore, these restaurants function as ‘private’ entities that exploit a loophole tacitly accepted by the indigenous population, allowing foreign visitors to follow different cultural values. Both sides are engaged in an uneasy complicity in face of the overarching process of capital accumulation.

Nonetheless, the issue of appropriate dress and behaviour on the part of the non-Muslim expatriate population has led to the launch of an anti-indecency campaign within Dubai’s malls. From an Emirati perspective, the scenario is one whereby the indigenous population does not ‘want to generalize and say that all expats behave in that inappropriate way. However, many expats who come to our country are either not aware of our cultural norms or are just not respectful of them and choose to behave any way they want to.’32 But conversely, as one western expatriate was reported as saying: ‘I respect Dubai, its religion, culture and people. I come here frequently for business and pleasure, and I was never asked to cover my shoulders or knees until recently … besides I don’t have long or covered outfits, and most importantly I didn’t do something bad to Dubai or its people.’33 So if the shopping mall serves to bring Dubai the status of a global entrepot centre, it clearly has some way to go to breach a divide – which in many ways it actively undermines – between cultural practices that appear to exist in relatively autonomous spheres.

9.6 Gold Souk at the centre of the Dubai Mall

Within the Dubai Mall, a far more explicit attempt to integrate a sense of cultural authenticity can be seen. Occupying the central point of its plan, in the void between its three interlinked malls, the Dubai Mall has a beating heart in the form of a fake souk which specializes in selling gold. Predictably it is also the world’s largest. The mall’s designers hoped for an explicit place-specific message to be imparted via this ‘symbolic integration of Arabic culture’ into its overall fabric.34 But, unfortunately, this part of the mall is all too easily bypassed by the shopper, being zoned off the beaten track, rather than integral to the main circulation paths. This is reinforced by the shiny newness of the interiors, whose aesthetic errs toward a generic representation of luxury brand consumption, rather than the more nuanced and culturally hybrid experience the traditional souk offers. It is this sheer lack of spatial differentiation that in the end is most problematic. As a destination within a cityscape of the world’s biggest things, the Dubai Mall offers little more than the narrow definition of ‘world class’ to which it aspires. It is a fleeting moment of being that will soon be superseded by its competitors – and what then? An alternative set of criteria are required to navigate the destinations within this landscape of consumption.

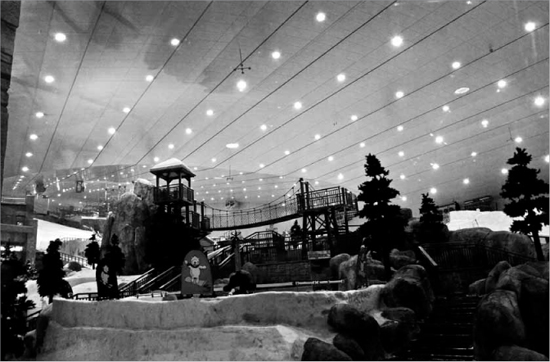

At the extreme end of the scale is the scarcely believable indoor ski-slope whose prosthetic form sticks out of the side of the previous holder of the title of Dubai’s largest shopping centre, the Mall of the Emirates. Here one is reminded of Rem Koolhaas description of airports as being ‘a concentrate of the hyper-local and hyper-global in the sense that you can get goods there that are not available even in the city, hyper-local in the sense you can get things there that you get nowhere else.’35 Although clearly successful – the Mall of the Emirates was as busy as any I visited during my research – there is still a hefty environmental price tag required to sustain this fantasy, as well as the others. While the relatively small size of Dubai positions it well behind the USA and China in terms of overall carbon consumption, the city now holds the unenviable distinction of ‘having the highest ecological footprint per capita’ anywhere on the planet.36 Viewed within an understanding of the nature of the economic processes which underpin the cityscape – albeit that the credit bubble on which Dubai’s speculative property boom was built was well and truly burst by the global financial crash from 2008 (although it has since recovered somewhat)37 – it is difficult to imagine a volte-face whereby the Dubai of the future could exist without the air-conditioned environments that make the desert habitable for its large expatriate population. Nonetheless, the environmental excess attached to strategies of differentiation in the city’s malls is simply unsustainable in the longer term. It is surely more fruitful to engage with forms and spaces that are more demonstrably appropriate to patterns of human habitation in this specific context.

9.7 Indoor ski slope at the Mall of the Emirates

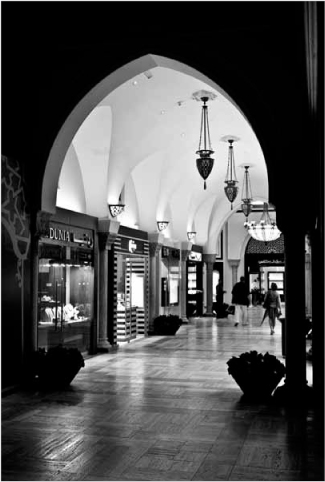

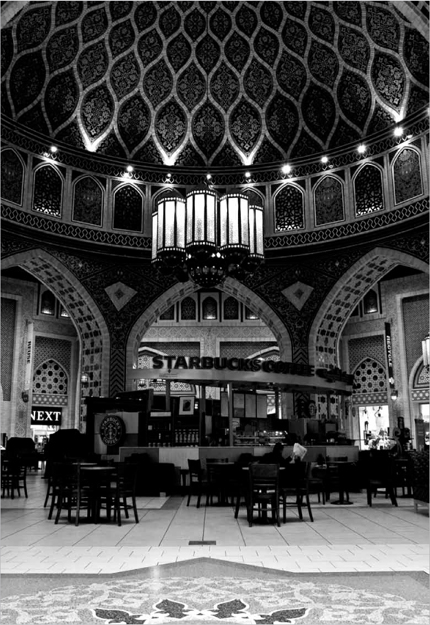

Our next precedent promises a more nuanced blend of global and local ingredients. Conceived as a recreation of ‘life as it used to be for residents along Dubai Creek, complete with waterways, abras, wind towers and a bustling souk’, the Madinat Jumeirah resort development, opened in 2003 by the architect/developer, Mirage Mile, borrows its imagery heavily from the remnants of the old city preserved in the Bastakiyah Quarter.38 On first entering the imitation souk that forms the centerpiece of this luxury resort, the faithfulness with which these fragments are re-assembled compresses, in psychogeographical terms, the distance from the traditional city. Here the usual ‘dumbbell plan’ of the shopping mall is abandoned in favour of ‘meandering paths [that] lead visitors through a bazaar-like atmosphere in which open fronted shops and intimate galleries spill onto the paved walkways’.39 Already bounded by Dubai’s impassable road structure, this building realises that it doesn’t need the forced movement of the mall to stimulate a captive audience into acts of consumption. Rather, this conscientious reconstruction of the spatiality of the souk evokes Bernard Tschumi’s analysis of the design of the garden as a space of leisure which merges ‘the sensual pleasure of space with the pleasure of reason, in a most useless manner’.40 The Madinat Jumeirah seems therefore to be a refreshing change, though one that requires further investigation to avoid falling into the trap of simple post-structuralist awe which so often prevent meaningful critiques of shopping centres.

9.8 Historic wind-towers in the Bastakiyah Quarter of Dubai

9.9 Bastakiyah’s textile souk

It is in the things that are absent (heat, smell, mess, hustle and bustle, unplanned forms of inhabitation) that the superficial conceit of the language of the Madinat Jumeirah becomes apparent. Here again, the muted presence of globalized brand imagery comes to the fore. The quick realisation that its stalls offer not the informal, bottom-up spaces of consumption of Dubai’s old souks, but instead a cleverly disguised version of the usual suspects from the generic shopping mall the world over, questions the ‘reality’ we are faced with here. It’s a question reinforced by the simulations of Bastakiyah’s traditional wind-towers around the mall’s exterior. In principle these might be a legitimate way to find a more sustainable means to control the internal climate, but of course these catchers of the wind do nothing of the sort; their presence in form but not function brings any higher sense of aspiration quickly down to earth. It can be read as a representation, as Homi Bhabha notes, that is undermined by the problematic production of a ‘recognizable Other, as a subject of a difference that is almost the same, but not quite’.41

For the almost exclusively white, wealthy, western clientele who use the Madinat Jumeirah shopping centre as part of their Dubai holiday, it has become a legitimate substitute – during my visit, one well-heeled gentleman was using it enthusiastically to introduce his equally well-heeled girlfriend to the experience of a ‘real’ Arabian souk. It hence provides a representation of cultural authenticity for a market that wants to believe they are engaging with the locality, but ultimately wants to be able to eat English fish-and-chips rather than try anything more challenging. Once again, a field of difference is opened between the indigenous and expatriate idea of what Dubai is, limiting a more engaged condition of cultural hybridity or any deeper sense of social capital in its structure.

9.10 Malls at the Madinat Jumeirah resort development

9.11 Wind-tower motifs at the Madinat Jumeirah in Dubai, UAE, with the Burj Al Arab Hotel beyond

The final stop on our Dubai tour is one that invokes historical narrative to evoke a sense of cultural legitimacy. The Ibn Battuta Mall constructs a story based on the travels of the famous 14th-century Muslim scholar. Structured around a loose ‘dumbbell plan’, the mall is separated into six ‘events’ themed to represent a particular stop on Ibn Battuta’s travels. Thus under one roof it seems possible to visit Andalusia, China, Egypt, India, Persia and Tunisia. Unlike the Madinat Jumeirah resort, however, there is little attempt to recreate an authentic, robust representation of Dubai’s culture. Instead, it is an environment that is unashamedly artificial, revelling in its fantasy narrative.

Situated on the limits of new Dubai, some 30 km away from its historic core, the Ibn Battuta Mall seems to offer little in the way of architectural merit, yet it does encapsulates a number of characteristics of this Emirati state. More than any of the self-conscious environments in other Dubai malls, the spaces convey some sense of the freewheeling trading spirit implicit in the city (see Plate 15). Likewise, the inward, autonomous nature of the Ibn Battuta Mall, by visibly keeping the threat of the adjacent Jebel Ali power plant and the encompassing desert at bay, conveys a more problematic schism underlying Dubai as a whole. This unease is enhanced by the sight, all around this outlying mall, of countless immigrant workers labouring in the ferocity of the desert heat to put up large projects they will never be allowed to inhabit.42 It is a stark reminder of an apparent global inclusiveness that is in fact being built on the exploitation of an immigrant underclass whose existence is rendered invisible by the autonomous structures they are creating. This inward-looking, capitalist urbanity falls into that most post-modern of traps – a static sense of being, inherently limited in terms of transformative potential by the nature of its built form. The issue then is, from these apparently limited circumstances, what might Dubai become in the years to come?

9.12 Advert within the malls of the Madinat Jumeirah resort

9.13 ‘Chinese’ section of the Ibn Battuta Mall in Dubai, UAE

9.14 ‘Indian’ section of the Ibn Battuta Mall

9.15 ‘Persian’ section of the Ibn Battuta Mall

CONCLUSION

George Katodrytis describes Dubai as a ‘prototype of the new post-global city, which creates appetites rather than solves problems. It is represented as consumable, replaceable, disposable and short-lived … Dubai may be considered the emerging prototype for the 21st century: prosthetic and nomadic oases presented as isolated cities that extend out over the land and sea.’43 While this chapter touches on certain characteristics of the geo-political framework and emerging spatiality that go hand-in-hand with this reading of Dubai, it remains the case that it is still a relatively young city whose urban qualities feel wanting in some respects. As Christopher Davidson points out: ‘Dubai’s remarkable development strategies will never reach their full potential unless … a civil society exists’.44 Thus the fundamental obstacles are the separate spheres of existence defined by a patrimonial Emirati ruling class, a moneyed class of expatriate workers and tourists, and a relatively invisible underclass of migrant workers. It is, on the face of it, a highly striated class structure whose lack of genuine interaction is exacerbated by the stretched out, island-like autonomy which defines much of its urban condition. Yet, in concept at least, Dubai defines itself as a culturally hybrid dynamo striding ahead of the more conservative ideals of neighbouring Emirati states.

Dubai’s shopping malls visited for this chapter embody this paradox. While each displays characteristics and innovations from its locality, it is also in the nature of this building typology to exhibit its worst traits through its own insularity. It would be all too easy to fall back on westernised urban discourse to interpret this condition as an inherently weak, divisive urban structure in constant denial of its own history, which only leads each successive development in pursuit of an insatiable appetite for being bigger and better than the rest. Rather, I would posit that the different type of urban space that Dubai clearly consists of demands a different – or at least updated – kind of urban theory to understand its fundamental characteristics. The need for this process is even more important as Dubai is being forced to reevaluate its building stock, both in the wake of the current global recession which has temporarily slowed down its real-estate boom, and the opening of a metro system which threatens to liberate much of the stretched-out city for a larger portion of the populace.

It would be folly to believe these two circumstances will in themselves imply an overall shift in terms of what Dubai ultimately becomes. Both however imply a change away from Dubai’s present striation toward a ‘smoother’ type of space, one that is ‘identified with movement and instability through which stable territories are erased and new identities and spatial practices become possible’.45 Accordingly it is in analysing the shopping mall not so much as a ‘despotic signifier’ of identity, but rather as a field of social interaction within a wider urban structure, that a far more productive understanding of Dubai can be pursued. Far from representing the death of the city, it might yet be that the things we choose to do in shopping centres are capable of producing their own culturally hybrid histories, and in so doing can transcend the apparent limitations of the format. It is even possible that due to Dubai’s intense climatic, economic, social and cultural conditions, it could act as one of the crucibles for the future transformation of the shopping mall, should the necessary freedom of expression be allowed.

NOTES

1 Christopher M. Davidson, Dubai: The Vulnerability of Success (London: Hurst & Company, 2008), pp. 91–98.

2 Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (London: Penguin, 1961), p. 25.

3 Davidson, Dubai, p. 103.

4 Ibid., pp. 92–93.

5 ‘Jebel Ali’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jebel_Ali (accessed 5 October 2009).

6 ‘Oil Reserves’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_reserves (accessed 5 October 2009).

7 ‘Oil and Gas’, UAE Government website, http://www.uae.gov.ae/Government/oil_gas.htm (accessed 5 October 2009).

8 Davidson, Dubai, p. 106.

9 ‘Dubai’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dubai (accessed 5 October 2009).

10 Ibid.

11 Saskia Sassen, Cities in a World Economy (3rd Edition, London: Pine Forge Press/Sage Publications, 2006), p. 112.

12 Mike Davis, ‘Sand, Fear and Money in Dubai’, in Mike Davis & Daniel B. Monk (eds), Evil Paradises: Dreamworlds of Neoliberalism (New York: The New Press, 2007), pp. 51–52.

13 David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry Into the Origins of Cultural Change (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1990), p. 109.

14 Victor Gruen, Shopping Towns USA (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1960). See also: Jeffrey M. Hardwick, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of and American Dream (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); Alex Wall, Victor Gruen: From Urban Shop to New City (Barcelona: Actar, 2005).

15 Kim Dovey, Framing Places: Mediating Power in Built Form (London/New York: Routledge, 1999), p. 4.

16 Nicholas Jewell, ‘The Fall and Rise of the British Mall’, The Journal of Architecture, vol. 6, no. 4 (Winter 2001): 317–378.

17 Rem Koolhaas; ‘Singapore Songlines’, in Rem Koolhaas & Bruca Mau, S, M, L, XL (Rotterdam/New York: 010 Publishers/Monacelli, 1995), p. 1073.

18 ‘Dubai Shopping Festival’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dubai_Shopping_Festival (accessed 5 October 2009).

19 Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1994), p. 151.

20 ‘Bur Juman’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BurJuman (accessed 5 October 2009).

21 Eric R. Kuhne and Associates, ‘Bur Juman Gardens’, Civic Arts website, http://www.civicarts.com/bur-juman-gardens.php (accessed 5 October 2009).

22 Gruen, Shopping Towns USA, p. 74.

23 Jewell, ‘The Fall and Rise of the British Mall’.

24 ‘Burj Dubai (Dubai Tower) and Dubai Mall, United Arab Emirates’, Design/Build Network website, http://www.designbuild-network.com/projects/burj/ (accessed 5 October 2009).

25 ‘List of the World’s Largest Shopping Malls’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_largest_buildings_in_the_world#List_of_the_world.27s_largest_shopping_malls (accessed October 2009); It should be noted that the overall floor areas are disputed for a number of malls on the list, and while the New South China Mall currently assumes the mantle of ‘largest’ based on gross leasable area, it is, at the time of writing largely empty. On this point, see also the Wikipedia entry at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:List_of_largest_buildings_in_the_world#Mall_areas (accessed 5 October 2009), as well as Donohue, M., ‘Mall of Misfortune’, 12 June 2008, The National website, http://www.thenational.ae/article/20080612/REVIEW/206990272/1042 (accessed 5 October 2009).

26 ‘Dubai Mall’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dubai_Mall (accessed 5 October 2009).

27 Koolhaas, ‘Bigness, or the problem of Large’, in S, M, L, XL, p. 515.

28 DP Architects PTE Ltd, ‘Dubai Mall’, DP Architects website, http://www.dpa.com.sg/main.html (accessed 5 October 2009).

29 Davis, ‘Sand, Fear and Money in Dubai’, p. 54.

30 Stuart Hall, ‘Who Needs Identity?’ in Stuart Hall & Paul du Gay (eds), Questions of Cultural Identity (London: Sage Publications, 1996), p. 12.

31 Ibid., p. 14.

32 Fatma Salem, ‘Dubai Malls Join Anti-Indecency Campaign’, 8 August 2009, Gulf News website, http://www.zawya.com/Story.cfm/sidGN_08082009_10338386/Dubai%20malls%20join%20anti-indecency%20campaign/ (accessed 10 November 2009).

33 Ibid.

34 DP Architects PTE Ltd, ‘Dubai Mall’, http://www.dpa.com.sg/main.html (DP Architects website, accessed October 2009).

35 Koolhaas, ‘The Generic City’, in S, M, L, XL, p. 1251.

36 Landais, E., ‘UAE tops world on per capita carbon footprint’, 30 October 2008, Gulf News website, http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/uae/environment/uae-tops-world-on-per-capita-carbon-footprint-1.139335 (accessed 10 November 2009).

37 ‘Shares Hit by Dubai Debt Problems’, 20 November 2009, BBC News Online website, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/8381258.stm (accessed 10 November 2009).

38 ‘Madinat Jumeirah’, Wikipedia entry, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madinat_Jumeirah (Wikipedia website, accessed 10 November 2009).

39 ‘Souk Madinat’, Jumeirah Hotels website, http://www.jumeirah.com/Hotels-and-Resorts/Destinations/Dubai/Madinat-Jumeirah/Madinat-Souk/ (accessed 10 November 2009).

40 Bernard Tschumi, Architecture and Disjunction (Cambridge, MA/London: The MIT Press, 1996), p. 86.

41 Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 122.

42 Davis, ‘Sand, Fear and Money in Dubai’, pp. 48–68.

43 George Katodrytis, ‘Metropolitan Dubai and the Rise of Architectural Fantasy’, Radical Urban Theory website, http://www.radicalurbantheory.com/misc/dubai.html (accessed 18 September 2009).

44 Davidson, Dubai, p. 209.

45 Kim Dovey, Becoming Places: Urbanism/Architecture/Identity/Power (London/New York: Routledge, 2009), p. 22.