This chapter investigates the role of acoustics in shaping the experience of movement in buildings and landscapes. Two case studies, one outdoor space and one indoor space, are used to explore the ways in which sound provides a full and nuanced understanding of one’s environment. The experience of threshold, often articulated in architecture and landscape with material and spatial transitions, is also experienced in large part through changes in reverberation time and levels of ambient noise. Changes in the surrounding materials can transform the sound of one’s own footsteps, and moving through a threshold can suddenly introduce ambient sounds that transform one’s perception of a place. Drawing on extensive research in the quantitative description of soundscapes, the author presents current acoustical research in terms of our understanding of the ways that sound shapes the experience of movement.

Factors shaping our sound experience: sound, space and listener

Our sound experience is affected by various characteristics of sound sources. The overall sound level is certainly a critical factor. It is also important to consider the characteristics of the sound spectrum. For example, noise annoyance could be increased with more tonal components. Moreover, with a given energy summation, noise annoyance may increase with a larger amplitude fluctuation or emergence of occasional events. Other factors that affect noise annoyance include regularity of events, maximum sound level, rise time, duration of occasional events, spectral distribution of energy, and number and duration of quiet periods. The movements of a sound source, or listener, can change the relative positions of source and receiver, changing all the above factors correspondingly, which, in turn, will change our sound experience. Sounds that are far away, close up or moving in juxtaposition to a listener may provide different information and thus affect the experience. It has been shown that psycho-acoustic qualities differ between stable and passing sounds.

In addition to sound-source characteristics, the acoustic effects of a space are also vital for our sound experience. When sound impinges on a boundary, it may be absorbed partly or totally, or be reflected in one direction or another, and so various sound fields can be formed. Reverberation time, the time for a relatively loud sound to become inaudible in a space, is an important index for the acoustic environment in indoor as well as outdoor spaces, such as streets and squares. It has been demonstrated that, with a constant sound level, noise annoyance is greater with a longer reverberation. On the other hand, a suitable reverberation time, say 1–2 seconds, can make street music more enjoyable. Whereas, in a regularly shaped, fairly reflective enclosure, the sound field may be relatively even, both sound level and reverberation being consistent across the space, there are spaces offering significant changes in sound level and reverberation, so that, when the listener moves, he or she enjoys a varied sound experience. Compared with visual space, aural space is more spherical and all surrounding, with less feeling of boundaries, and it tends to emphasise the space itself, rather than the objects in the space. Sound provides dynamism, helping people to get a sense of the progression of time and the scale of space and encouraging involvement.

On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that correlations between sound evaluation and acoustic factors are often not high, whereas non-acoustic factors relating to listeners play a major role. According to Guski, the noise annoyance to inhabitants depends only on approximately 33 per cent of acoustic parameters such as acoustic energy, number of sound events and length of moments of calm between intermittent noises.1 It is important to consider the sound sensitivity of individuals, as well as the meaning of sounds for them. Moreira and Bryan suggested that those with high noise susceptibility might be persons who show interest in and have sympathy with others, have a great awareness of their environment and are intelligent and creative.2 The perception of noise significantly depends on attitude, including fear, cause of noise, sensitivity to noise, activity, perception of the neighbourhood and the global perception of the environment. The effects of various social and demographic factors are also of great importance. For example, the assessment of the sound quality of an urban area depends on how long people have been living there, how they define the area and how much they have been involved in local social life. Expectation is another issue in sound evaluation. In fact, noise regulations are based on an assumption that people expect a different noise environment depending on the quality of the place. Behaviour and habits are important too, including, for example, the opening and closing of windows and the use of balconies or gardens. Season and the time of day may also influence sound evaluation. It has been reported that noise annoyance is greater in summer than in winter, and greater in the evening and at twilight. The idea and experience of an environment are historically conditioned refractions of cultural life. If there were no traffic noise, the soundscape in cities might be filled with church bells, from every direction, day and night. All those factors are related to movement, in terms of time, place and community, for example. On the other hand, people’s attitude could be affected by sounds. For example, it appears that loud noise reduces helping behaviour and induces a lack of sensitivity to others.3

Soundscape on the move: Sheffield Gold Route

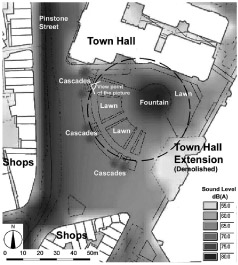

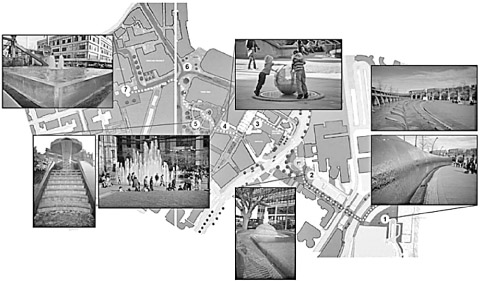

For centuries, the development of Sheffield was shaped by waterways. In the recent citycentre regeneration, starting in the 1990s, great efforts were made to ensure that the reconnection with the rivers continued to be fostered, and their role in the history of the city celebrated. Waterscapes and squares were embedded into the city for their vibrancy with respect to the history of Sheffield. Along the Gold Route, as shown in Figure 2.4.1a, a diversity of waterscapes was developed. A series of field questionnaire surveys in selected locations

Figure 2.4.1A The Gold Route in Sheffield, showing the waterscape and the city: (1) Sheaf Square, (2) Howard Street and Hallam Garden, (3) Millennium Galleries and Winter Garden, (4) Millennium Square, (5) Peace Gardens, (6) Town Hall Square and Surrey Street, (7) Barkers Pool Gold Route are shown in Figure 2.4.1b.4

Source: Jian Kang

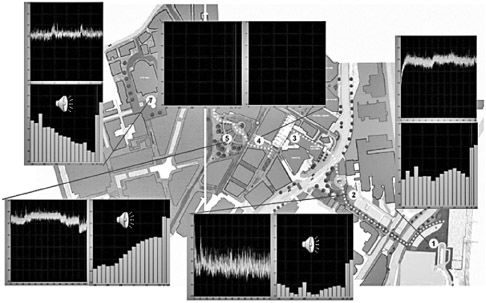

Figure 2.4.1B Changes in waterscape sound levels with frequency and time at different locations of the Gold Route, measured at 1 m from each water feature

Source: Jian Kang

showed that water sounds are the most preferred sounds in the soundscape.5 Correspondingly, the changes of waterscape sound levels with frequency and time at different locations of the

Sheaf Square provides interesting and enjoyable soundscapes. There are a number of water features, and the measurements show that they vary considerably in terms of spectrum and dynamic process. It is interesting to note that the steel barrier efficiently reduces noise from the busy road, as well as generating pleasant water sounds. It is a successful soundscape element, creating an interesting sense of movement in terms of sound source and space. The water features at Howard Street have relatively large dynamic ranges, and the spectra are also rather different from other water features along the Gold Route. Together with the visual effects, the water features greatly enhance the richness and diversity of the waterscapes and soundscapes along the Gold Route. Although the sound of water features is normally pleasant, helping to distract people’s attention from unwanted sounds such as traffic, silent water features in the Millennium Square, with their significant visual effect, can play a similar role. Because of the low sound level, people often turn their attention to such water features, even from a distance, as they move forward trying to hear the sound. Their attention is attracted, producing an effective attention masking.

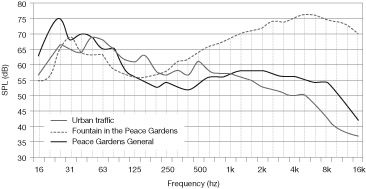

At Peace Gardens, there are two main sound sources, the fountain in the middle of the square and a road with traffic on one side. The transformation of soundscape is demonstrated in Figure 2.4.2a, with a soundscape map showing sound pressure level and overlapping sound fields from different sources. With the movement of a listener, the soundscape changes can be perceived in terms of sound level as well as sound meaning. To further analyse soundscape maps, a comparison of spectra is given in Figure 2.4.2b, with the measurement made close to the sound sources. It can be seen that there are considerable differences between the spectra, and, when moving across the square, a listener can experience a rich soundscape, changing gradually from a water spectrum to a traffic spectrum, for example. The perception of the soundscape is more complicated than just level and spectrum, for the first noticed sound may not be the loudest one; rather, it would be the water sound as a soundmark, based on a large-scale questionnaire survey in the square.6 Schafer (1977) defined sounds as keynotes, foreground sounds and soundmarks.7 Keynotes are in analogy to music, where a keynote identifies the fundamental tonality of a composition, around which the music modulates. Foreground sounds, also termed sound signals, are intended to attract attention. Sounds that are particularly regarded by a community and its visitors are called soundmarks, in analogy to landmarks.

Figure 2.4.2B Spectrum comparison between different sounds in the soundscape of the Peace Gardens

Source: Jian Kang

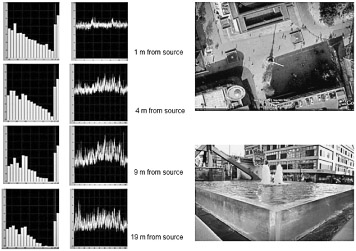

The soundscape at Barkers Pool is also rich, and, interestingly, the water feature has distinguishable low-frequency components, as can be seen in Figure 2.4.1b. It is interesting to examine the change in soundscape when moving away from the water feature, as shown in Figure 2.4.3, in terms of spectrum and dynamic sound-level changes with time. The richness of soundscape within a relatively short distance can be clearly seen, which gives considerable scope for soundscape design.

Figure 2.4.3 Change of soundscape when moving away from the water feature in Barkers Pool

Source: Jian Kang

Indoor soundscape: long enclosures

A common indoor space type that is closely related to movement is the long enclosure, where one dimension is very long, and the other two are relatively short. Such spaces include, not only underground shopping streets and subway stations, but also corridors and concourses in public spaces. In long enclosures, it has been shown that reverberation time generally increases with increasing source–receiver distance, which is fundamentally different from that based on classic formulae, which attribute a single value to the whole space. In terms of sound distribution, fundamental differences between a classic sound field and the sound field in long enclosures have also been demonstrated. That is, instead of becoming stable beyond the reverberation radius, the sound level in long enclosures decreases continuously along the length. Another influencing factor concerns the boundary conditions. For example, between sound fields resulting from geometrical and diffuse boundaries, there are considerable differences. In the case of multiple sources, it has been demonstrated that the reverberation is dependent on the number and position of the sources.8 Those basic acoustic features, in terms of changes in reverberation and sound level, can greatly enhance the sense of movement when a listener is moving through such spaces.

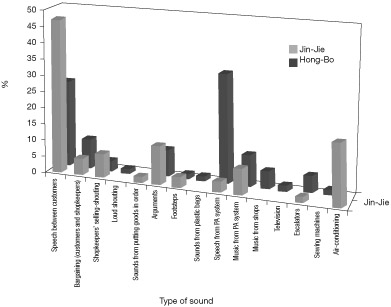

The richness and variation in soundscape are further enhanced by the presentation of various kinds of sound source. A large-scale questionnaire survey was carried out in two typical underground shopping streets in Harbin City, China, namely Jin-Jie and Hong-Bo. Figure 2.4.4 shows the first sounds noticed by interviewees. It can be seen that there are considerable differences between the two sites. For example, in Jin-Jie, the most noticeable sound was ‘speech from PA systems’ (31.4 per cent), whereas, in Hong-Bo, the most noticeable sound was ‘speech between customers’ (46.9 per cent). The differences might have been caused by variations in sound sources and/or in the profiles of interviewees who were paying more attention to particular sounds, but it could also be caused by the effects of sound fields on the propagation of different sources. It is, therefore, important to design the sound fields in terms of sound attenuation along the length, considering the spectrum change due to boundary absorption and diffusion at different frequencies. In other words, improvements in soundscape could be made by better balancing different sound sources in terms of their levels and spectra, and this could be different on a route of movement.

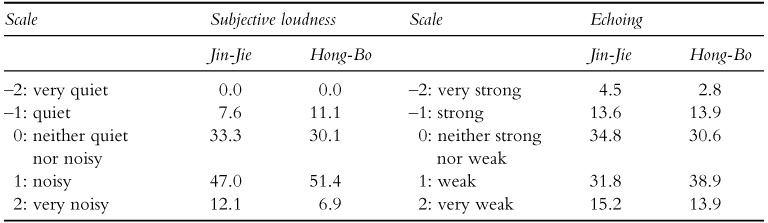

Table 2.4.1 Evaluation (%) of the acoustic environment and echoing in the two underground shopping streets

It also proved useful to examine the evaluation of soundscape and sound preference in underground shopping streets. Table 2.4.1 shows the evaluation of the general acoustic environment in the two underground shopping streets cited above. Both sites were rated by about 60 per cent of the interviewees as ‘noisy’ or ‘very noisy’. This means that, in such spaces, noise control is still an important issue, for which it is essential to consider the special acoustic features of long enclosures. In Table 2.4.1, the evaluation of echoing is also shown. Fewer than 20 per cent of the interviewees selected ‘strong’ or ‘very strong’, suggesting that, generally speaking, such spaces are not reverberant, and the control of reverberation may not be the top priority in designing the soundscapes.

Notes

1 R. Guski (1998) Psychological determinants of train noise annoyance, Proceedings of Euro-Noise, Munich, Germany, vol.1, pp. 573–6.

2 Naomi Moreira and M. Bryan (1972) Noise annoyance susceptibility, Journal of Sound and Vibration, vol. 21, pp. 449–62.

3 Gifford 1996; Richard A. Page (1997) Noise and helping behavior, Environment and Behavior, vol. 9, pp. 311–34.

4 Jian Kang (2012) On the diversity of urban waterscape, Proceedings of the Acoustics, Joint meeting of the French Acoustical Society and UK Institute of Acoustics, Nantes, France.

5 Wei Yang and Jian Kang (2005) Soundscape and sound preferences in urban squares, Journal of Urban Design, vol. 10, pp. 69–88.

6 Wei Yang and Jian Kang (2005) Soundscape and sound preferences in urban squares, Journal of Urban Design, vol. 10, pp. 69–88.

7 Schafer 1977, 1994.

8 Kang 2002.