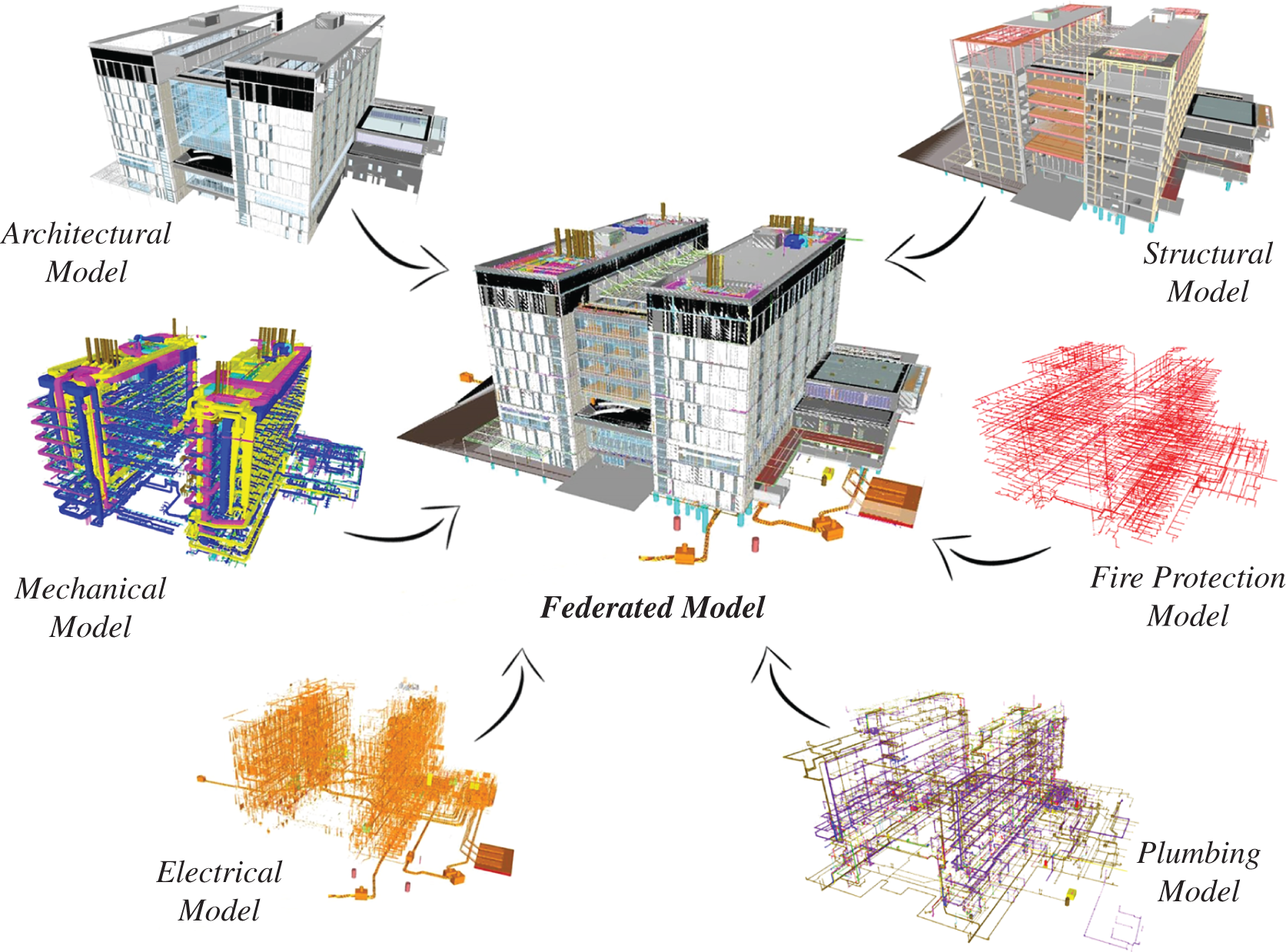

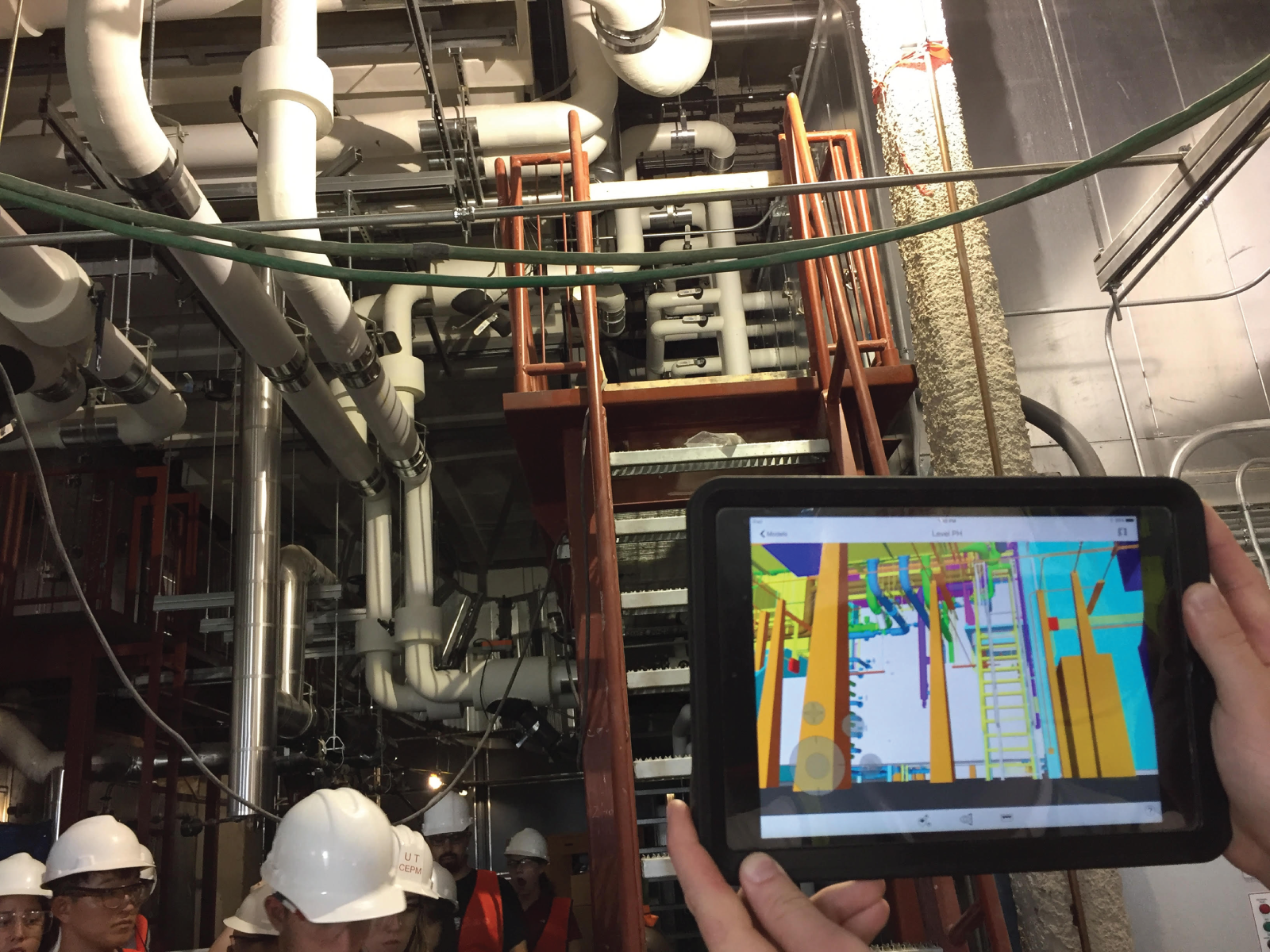

The VDC coordination team is usually part of the general contractor (GC) and manages the entire BIM design coordination process. This chapter covers specific guidelines for GCs and VDC coordinators, and discusses the roles and responsibilities of the VDC coordinator/BIM manager in the design coordination process, starting with setting up the project’s BIM project execution plan (PxP). The chapter also discusses interfaces of the VDC team with other project teams, such as owners, designers, and subcontractors. A case study of an academic building is presented and describes the GC’s roles in the VDC process that are related to design coordination. Note that chapters 5, 6, and 7 follow a similar structure, as each of these chapters is meant to provide specific guidelines for different stakeholders: chapter 5 for GCs and VDC coordinators, chapter 6 for designers, and chapter 7 for subcontractors and fabricators. As well stated by Eastman et al. (2011), a critical function of any GC is trade and system coordination. Design coordination allows for design integration by different specialty designers and contractors to create a single, coordinated set of designs that can be built without clashes between components, reducing design errors. Effective design coordination can prevent cost overruns, schedule delays, and general disruptions caused by only identifying issues in the field, as designers and subcontractors will better understand their scope of work and how they will interface with other disciplines. Design coordination becomes more critical in complex facilities, such as hospital buildings, where there may be many different building services that are being installed by different stakeholders, and that need to be installed in relatively confined spaces. Although there were architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) professionals ahead of the curve and already using some form of 3D spatial coordination in the mid-1990s, the majority began using 3D spatial coordination with the wider adoption of building information modeling (BIM) in the mid-2000s. The transition from 2D to 3D design coordination meant the process became much more efficient and effective. We can now detect more clashes ahead of time, preventing design errors and clashes between systems from causing disruptions in construction. And by integrating multiple perspectives in the process, including owners and future operators of the facility (i.e., facility managers), we can also prevent systems from being installed in a manner that makes their maintenance more difficult or even impossible. The GC, then, has the key role of setting up and managing the design coordination process in a digital environment, ensuring that the process is well organized and efficient. This chapter covers specific guidelines for GCs and VDC coordinators and discusses the roles and responsibilities of the VDC coordinator/BIM manager in the design coordination process, starting with setting up the project’s BIM project execution plan (PxP). The chapter also discusses interfaces of the VDC team with other project teams, such as owners, designers, and subcontractors. A case study of an academic building is presented and describes the GC’s roles in the VDC process that are related to design coordination. Although design coordination is a collaborative process between multiple project stakeholders (e.g., owner, designers, general contractor, and subcontractors), the process of coordinating designs involves first detailing an engineer’s design into a fabrication model (i.e., LOD 400). It is important to note that mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and fire protection (MEPF) subcontractors’ development of a fabrication model is not design service. Rather, it is a translation in 3D of an engineer’s design, which aims at enabling efficient and cost-effective construction and installation of the design. In other words, engineers remain responsible for design, and contractors and subcontractors remain responsible for construction and installation. FIGURE 5.1 Design coordination workflow GCs, hence, have the unique role of setting up, managing, and moderating the process of design coordination between multiple stakeholders. The GC’s BIM manager prepares the federated model for design coordination and performs initial clash-detection analyses and groupings, to ensure that the design coordination meetings run smoothly. BIM managers need to be well prepared to lead multidisciplinary teams of subcontractors. If we re-examine one of the figures originally shown in chapter 4 (now Figure 5.1) and focus on the GC BIM manager’s role, we can see that the GC has an important role in ensuring the efficiency of the design coordination process as a whole, leading most of the process. In order to accomplish this, GCs need to ensure that their representatives in the design coordination process have both technical skills and social skills, as they will need to work with a broad range of personality types and experience levels. For example, a subcontractor may have minimal 3D modeling experience, but you will still need to integrate their model into a federated model for design coordination purposes. In setting up a project for successful BIM-based design coordination, owners have the key role of establishing the ground rules in terms of project requirements with the GC and designers, which will then trickle down to subcontractors. Owner requirements should be clearly stated in contract language with the GC and reflected in the BIM PxP. The development of a detailed BIM PxP will also set up a framework for the project team in terms of expectations of BIM use in the project, including modeling requirements, file-sharing protocols, and team composition. The GC’s BIM manager should also consider the following best practices in preparation for BIM-based design coordination: FIGURE 5.2 Screen capture of an online design coordination meeting Source: Image courtesy Linbeck Group, LLC. GoToMeeting and Autodesk screen shots reprinted courtesy of GoToMeeting and Autodesk, Inc., respectively. FIGURE 5.3 Design coordination spatial hierarchy for a medical office building Source: Image courtesy Linbeck Group, LLC Table 5.1 illustrates sample roles and responsibilities of the GC, which can be included in a BIM PxP. The specific responsibilities of GCs shown in Table 5.1 are further detailed here: Typically, a GC’s BIM manager adapts a company’s BIM PxP template to each specific project. The BIM PxP outlines the BIM-related processes and procedures, especially with regard to design coordination, and should be approved by the owner. The GC’s BIM manager is responsible for tailoring the plan to meet the owner’s and project’s requirements. This plan then becomes the guiding document for all BIM-related processes and issues during the entire construction phase. When the BIM PxP is being tailored to the project specifically, the GC should set up a meeting with all subcontractors clearly describing expectations and priorities related to BIM in the project. After the BIM PxP is approved, the execution of BIM can begin. TABLE 5.1 Sample GC roles and responsibilities established in a BIM PxP A federated model is assembled from several models created by designers and subcontractors. The base model contains architectural and structural models. Each subcontractor then creates their models for their individual scopes of work (e.g., mechanical, electrical, plumbing, fire protection). These individual models are then sent to the GC’s BIM manager to be combined into a federated model, which contains the base model and all the subcontractor models. It is important to note that the level of development (see chapter 3, section 3.2 for a discussion of LOD) typically differs for the base model and subcontractor models. The base model is usually in LOD 300, while the subcontractor models are usually in LOD 400, which is why design coordination models are often said to be in LOD 350 (i.e., some elements are in LOD 300 and others are in LOD 400). In general, each BIM-related role is stipulated in the BIM PxP. The GC is typically required to have at least one BIM employee—a BIM manager—whose responsibility for a project is to maintain the design coordination model. The GC’s main BIM-related role should be that of managing the design coordination process and, at the end of the construction phase, delivering a federated as-built BIM to the owner, including all major trades (e.g., architectural, structural, mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and fire protection). The BIM manager prepares the federated model for design coordination and performs initial clash-detection analyses and groupings, to ensure that the design coordination session runs smoothly. The BIM manager is typically the designers’ and subcontractors’ main point of contact for BIM issues. The subcontractors commence their work once they receive design drawings and specifications from a project’s architect(s) and/or engineer(s). The information in the designers’ drawings are augmented and detailed by the subcontractors, with the development of shop drawings and details needed for installation, ensuring that the engineer’s design intent and prescribed system performance are maintained. The GC manages the process of receiving and distributing these various designs and specifications, including managing requests for information (RFIs) The BIM manager also runs the design coordination sessions during the construction phase. These sessions are usually held on a weekly basis and should follow the model development and submission requirements established in the BIM PxP. To prepare a federated model for design coordination sessions, the BIM manager receives each subcontractor’s model and manages file sharing and software coordination to ensure that each model is integrated with the federated model in a timely manner. Efficient file sharing allows clash detection and constructability analysis to be run smoothly. The GC’s project manager supervises the BIM manager and holds team members accountable for nonperformance. Assuming the base model (i.e., structural and architectural) is available in at least LOD 300, 3D modeling is done in model-authoring software by each individual subcontractor who will participate in the design coordination process. Subcontractors can use various model-authoring software systems, as long as they are in compliance with the established guidelines in the project’s BIM PxP. If design coordination is being carried out in Autodesk Navisworks Manage®, for example, then the model-authoring software system should be able to export a file that is readable in Navisworks while maintaining geometry, naming conventions, and color coding. A detailed BIM PxP developed by the GC and approved by the owner will also set up a framework for the project team in terms of expectations of BIM use in the project, including file-sharing protocols and coordination software. To prepare the model for the coordination meetings, the BIM manager records subcontractors’ models and manages file sharing and software coordination to ensure that each model is integrated with the federated model on time. Seamless file sharing allows clash detection and constructability analysis to be run accurately and smoothly. All files and content should be available and accessible at all times by all stakeholders through a platform that is managed by the GC’s BIM manager. The workflow shown earlier in this chapter in Figure 5.1 may vary, depending on whether the team is utilizing software that requires a BIM manager to import each individual model into a federated model (e.g., Autodesk Navisworks®) or if the team is using software where each subcontractor can upload the model themselves directly into a federated model (e.g., Autodesk BIM 360 Glue®). Either way, the general workflow is similar and can be adapted to your own company’s needs. The BIM manager should have strong software skills, as they will be “driving” the model in the design co ordination session and, hence, should feel very comfortable with the particular software system being u Each BIM-related role is stipulated in the BIM PxP. The GC is typically required to have at least one BIM employee—a BIM manager—who is responsible for oversight of the entire BIM process, including maintaining the federated model and managing the design coordination process with all related stakeholders. A large part of the work of BIM managers is related to facilitating effective collaboration and coordination between different project stakeholders. The BIM manager is typically the designers’ and subcontractor’ main point of contact for BIM issues. The BIM manager also runs the design coordination sessions during the construction phase. The BIM manager prepares the federated model for design coordination and performs initial clash-detection analyses and groupings, to ensure that the design coordination meeting runs smoothly. The GC’s project manager, thought their BIM manager, is in charge of supervising the BIM process and holding team members accountable for nonperformance. GCs need to ensure that their representatives in the design coordination process have both technical skills as well as social skills, as they will need to work with a broad range of personality types and experience levels. For example, a subcontractor may have minimal 3D modeling experience, but the GC’s BIM manager will still need to integrate their model into a federated model for design coordination purposes. Participants should be committed to the coordination schedule established by the GC’s BIM manager. Figure 5.1, shown earlier in this chapter, is an example workflow with specific tasks that the GC outlines early in the process, including pre- and post-meeting tasks. The BIM manager should create a collaboration environment in which all participants are compelled to proactively flag problems (even those that do not necessarily impact their scope of work), bring them to team discussions, propose solutions, and follow up in a timely manner. Following each design coordination meeting, each subcontractor makes corrections to their individual scopes in model-authoring software; new models are then sent to the BIM manager, who checks for any new clashes that might have been generated due to revisions. A revised model is then vetted in the subsequent week’s design coordination meeting. Participants should clearly document major coordination issue histories (times, causes, discussions, progression, solutions, and agreement). The BIM manager is responsible for keeping track of these, but the entire team needs to contribute actively. This process continues until an issue for construction model is agreed upon by all parties. The GC interfaces with all project teams, such as subcontractors, designers, and owners. The main BIM-related interface points are discussed next. Once the GC is selected, the owner should review, evaluate, and comment on the BIM PxP developed by the GC, to ensure that it is compatible with the owner’s expectations. If an owner organization’s BIM standard is in place, requirements for the BIM PxP should be included in that standard. The owner can also choose to require a BIM PxP from the designers as well, although the common practice in the United States is that the GC leads the BIM implementation in construction, especially with regard to design coordination. Once the project is underway, the owner should regularly check the model(s) and/or participate in weekly design coordination sessions. It is advisable that the owner conduct two kick-off meetings that are specifically BIM-related: one at the design phase, with the entire design team, as well as any major consultants. The first meeting should be led by the design team and its BIM lead. A second meeting should be held once the GC or construction manager is selected and should include the design team, GC team, and major subcontractors/construction trades. The second meeting should be led by the GC team and its BIM lead. Additional BIM review meetings can be called by the owner as the owner deems necessary. Such meetings can include compliance checks of the BIM PxP, visual examinations of federated models, and review of design coordination processes. Also, if an owner’s representative is in place, that individual may attend the weekly design coordination sessions led by the GC’s BIM manager. The owner should also facilitate model handover between designer and GC, assuming there are two separate contracts in place: between owner and designer, and owner and GC. If the owner chooses to have the design team also develop a BIM PxP, the GC should make an effort for its BIM PxP to align with that of the design team, assuming a delivery method in which the owner has separate contracts with designer and GC. While the GC runs a large part of the BIM design coordination sessions, the designer may also be required to employ at least one BIM manager. The designer’s BIM manager is responsible for updating the design model during the design and construction phase. The GC’s BIM manager uses the designer’s BIM manager as the point of contact for BIM issues related to the design. The GC may relay requests for information (RFIs) from subcontractors and/or other designers to the designer, to ensure that their design intent is maintained during the design coordination process. Due to the RFIs, necessary changes may have to be made in the design; designers respond to the RFIs with approval/disapproval to the requests for changes. Any design changes need to be reflected in the base model. The GC has an important role in ensuring the efficiency of design coordination, leading most of the process. A GC’s BIM manager will develop the project’s BIM PxP, which outlines BIM-related processes and procedures, especially with regard to design coordination, and should be approved by the owner. The GC’s BIM manager is responsible for tailoring the plan to meet the owner’s and project’s requirements. This plan will then become the guiding document for all BIM-related processes and issues during the entire construction phase. Before any subcontractors are signed to a project by the GC, the use of BIM should be stipulated in contract language. Each subcontractor should be required to abide by the BIM-related processes described in the GC’s BIM PxP to ensure successful design coordination. Each subcontractor should employ a 3D/BIM technician and/or respective lead project manager who will attend design coordination sessions and be responsible for resolving all model conflicts. At the start of the project, the GC will usually set up a meeting with all subcontractors, clearly describing expectations and priorities related to BIM in the project. During project execution, the GC moderates design coordination sessions (usually on a weekly basis), manages subcontractor record modeling and deliverables, and manages file-sharing/coordination software. The GC also relays RFIs from subcontractors and/or other designers to the designer, to ensure that their design intent is maintained during the design coordination process. After each design coordination session, the BIM technician implements the changes discussed in the model. Often, subcontractors implement changes during the design coordination sessions as well. Either way, each subcontractor should ensure that the model is updated for the next design coordination session and the design changes are communicated for construction execution. This case study describes a project’s BIM implementation from the GC’s perspective, specifically with regard to design coordination. The project is an academic building in the southern United States. The GC was hired as the construction manager at risk (CM@R), so the GC and lead designer had separate contracts with the owner. The building has over 430,000 square feet of open and flexible space for interactive learning, with state-of-the-art laboratories, open and closed spaces for study, a cafeteria, and a library. Attached to the south side of the building is a large auditorium with a 300-seat capacity. The construction of the complex started in 2015, with substantial completion in August 2017. The building, as seen in Figure 5.4, has a complex integration of systems that needed to be coordinated correctly to ensure a high-quality product. The most complex aspect of the project, from a mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and fire protection (MEPF) coordination standpoint, and where BIM use was most helpful, was the coordination of the plenum space used to house the facility’s building systems. The research laboratories required ductwork, plumbing, services, electrical, exhaust, fire protection, security, and controls to all fit in a very limited amount of space. These complex coordination challenges led the owner to stipulate the use of BIM in the contract with the GC. The objectives of using BIM on the GC’s behalf also aligned with these contractual goals. FIGURE 5.4 Federated model Source: Image courtesy Hensel Phelps Overall, the project had approximately 23 professionals involved in BIM execution. In general, each role was stipulated in the BIM PxP. The GC was required to employ two BIM personnel: a BIM manager and a project manager. The BIM manager’s sole responsibility was to maintain the construction coordination model. The BIM manager was the architect/engineer’s (A/E) and subcontractor’s main point of contact for BIM issues and ran coordination meetings during the construction phase. To prepare the model for the coordination meetings, the BIM manager recorded subcontractors’ models and managed file sharing and software coordination to ensure that each model was integrated with the federated model in a timely manner. This smooth file sharing allowed clash detection and constructability analysis to be run accurately. The project manager was in charge of supervising the BIM process and holding team members accountable for nonperformance. The architect/engineer was also required to employ at least one BIM manager. The A/E’s BIM manager was responsible for updating the design model with any design changes during the construction phase. The GC BIM manager used the A/E BIM manager as the point of contact for BIM issues related to design. At the beginning of BIM coordination, the designers provided a 3D model of the structural and MEPF systems. It was the subcontractors’ responsibility to collaborate in the construction of their respective systems. TABLE 5.2 Meeting types and frequencies Before any of the subcontractors were signed to the project, the use of BIM was stipulated in the contract. Each subcontractor was required to participate in executing the BIM plan as per the BIM PxP. Each subcontractor was to employ a 3D technician and/or respective lead project manager who would attend modeling meetings and coordination meetings and be responsible for resolving all model conflicts. After the coordination meetings, the BIM technician implemented the changes discussed in the coordinated model. Each subcontractor was responsible for ensuring that the model was updated for the next coordination meeting and the design changes were communicated for construction execution. The key to successful collaboration is clear communication and execution. Hence, a collaboration strategy was explicitly stated in the BIM PxP (and is shown in the box insert), which also outlined a coordination schedule to be followed by GC, designers, and subcontractors, as shown in Table 5.2. Subcontractors were responsible for delivering their models every Monday to ensure that the federated model assembled by the GC’s BIM manager was always up-to-date. A BIM coordination meeting was held every Tuesday. A file-sharing framework was established early on by the BIM manager, and specific file-sharing conventions were specified in the BIM PxP. Once subcontractors uploaded their models on Monday, the GC’s BIM manager imported each model into Autodesk Navisworks® manager to create the project’s federated model. The BIM manager ran an initial clash detection on that federated model. The weekly coordination schedule allowed stakeholders participating in the BIM coordination meetings to run through each floor of the building model as construction occurred, being ahead of construction by a few weeks. For coordination purposes, the GC established a hierarchy of elements that was used to moderate discussions in the design coordination sessions. This hierarchy was as follows: The systems toward the top of the list were given priority. In the case of subcontractors disagreeing about which system should relocate, the BIM manager and project manager gave their input based on cost and time efficiency. The solution to any clash was given careful consideration, to avoid consequential clashes when moving systems, as well as potential constructability issues. The coordination changes were recorded by the GC’s BIM manager, and subcontractors were in charge of updating their models in their own model-authoring software to reflect the decisions that were discussed in the meeting. This process was repeated for each level of the project until all subcontractors were able to sign off on a clash-free model. Only then were subcontractors able to execute the work described in the federated and coordinated model. The GC conducted quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) walkthroughs in the project to ensure that each subcontractor was installing their work in the agreed-upon locations, as shown in Figure 5.5. The GC encountered a few challenges in the implementation of BIM for design coordination in this project, including having to deal with subcontractors with varying levels of 3D modeling skills and obtaining 3D models from the designers. The level of sophistication, in general, of BIM implementation in this case study illustrates how much the industry has evolved in terms of BIM use in just one decade. When we compare this case study to the one presented in chapter 3, we can see striking differences. BIM was mandated in this case study by the owner at the start of the project; in the case study in chapter 3, BIM was implemented more as an experiment and learning tool for the GC. It was not even used by the subcontractors in design coordination; they opted to coordinate in 2D on a light table. In this chapter’s case study, the GC developed a BIM PxP; at the time of chapter 3’s case study implementation, using a BIM PxP was not a common practice in the United States. GCs and subcontractors slowly observed the many benefits of implementing BIM for design coordination during the last decade, which has led to increasing use of BIM in the industry as a whole. Over a decade ago, Hartmann et al. (2008) documented that projects were using BIM for only one to two application areas. Mostafa and Leite (2018) replicated Hartmann et al.’s methodology and applied it to 28 more recent case studies and found that projects were implementing BIM for, on average, four application areas, of which design coordination was the most-implemented BIM application area. Beyond using BIM for more functions/application areas in a project, the fact that stakeholders have attempted to formalize processes is a clear indicator of the maturity of BIM implementation in the industry. FIGURE 5.5 GC BIM manager conducting QA/QC of installed work This chapter covered specific guidelines for GCs and VDC coordinators, and the roles and responsibilities of the VDC coordinator/BIM manager in the design coordination process, starting with setting up the Project’s BIM Project execution plan (PxP). The chapter also discussed interfaces of the VDC team with other project teams: owners, designers, and subcontractors. A case study of an academic building was presented and described the GC’s roles in the VDC process that were related to design coordination.

Chapter 5

Specific Guidelines for General Contractors and the VDC Coordination Team

5.0 Executive Summary

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Role of the VDC Coordinator in the Design Coordination Process

BIM-related role

BIM-related responsibility

BIM manager

Project manager

5.3 Interfacing with Other Stakeholders

5.3.1 Owner

5.3.2 Designers

5.3.3 Subcontractors

5.4 Case Study: Academic Building in the Southern United States

Meeting type

Project stage

Frequency

Participants

BIM kick-off

Preconstruction

Once

GC, designers, owner

BIM PxP review

Construction

Monthly

GC, designers, owner

Construction progress reviews

Construction

Weekly

GC, designers, owner

BIM coordination meetings

Construction

Weekly

GC, designers, subcontractors

5.5 Summary and Discussion Points

References