Study and Travel 1920s–1930s

It is too easy to let life pass on, over us, instead of entering into it, becoming truly alive, and turning it into something dynamic and fit to interpret great meaning and purpose.1

Alan Powers sees the 1930s as the defining decade for British Modernism.2 Through Mary Crowley’s diaries, we gain access to a creative world which, for some among this particular generation and social class, was thrilling. The diary entries are richly descriptive: they have an urgent tone, eager to record, so as not to forget, the sights, sounds, smells, thoughts and observations that might otherwise dissipate with time. Here we find fine descriptions and sketches of landscapes and buildings, and while thoughts and comments on these weave through the travel journals, Mary’s feelings about her self, her place in the world and her relationships with others are rarely stated. Travel has always been an imperative for young architects and this period of the early 1930s, a significant moment for Modernism in Europe, led her to visit significant growth points. However, travel for a lone young woman, even an architecture student, was not at that time an easy matter. Holidays had generally been taken with her parents and while these were mainly for leisure and pleasure, occasionally, due to her father’s keen interest in architecture and design and especially in environments for the young, there were outings to view significant sites facilitated by introductions from contacts at home.

In general, opportunities to visit and to draw sites of specific interest were seldom missed. Through such activities we glimpse something of Mary’s early reaction to Modernism a response which would have been expected of any student of architecture at the time. For example, on returning from Switzerland to take up her place at the Architectural Association (AA), Mary travelled with her mother via Paris and on the way took a detour by taxi, to view one of the new houses designed by Le Corbusier, viewed from the outside only. This was possibly the recently completed Maison Planeix which combined an artist’s studio and family living space.3 One gets the impression, however, from her frequent commentaries on the textures and colours of brickwork that the white walls of Modernism never quite won her over. This, as we shall see, was reflected later in a shift from concrete to brick and from prefabrication to traditional methods in the schools she became directly involved in planning.

2.1 Mary Crowley in the1930s. DLM personal collection

London, and especially Bedford Square in Bloomsbury was Mary’s base, a city that according to the architect Maxwell Fry was at the time, ‘a living centre of the arts’.4 For five years from 1927 to 1932 Mary studied architecture at the AA. The AA, formally established in 1890, was at this time the most prestigious architectural school in the country with an international reputation. She was one of a cohort of 59, of whom 11 were female students.5 The AA had only recently, in 1917, opened its doors to women and there was still a prevailing expectation that architectural students would be young middle-class males.6 Female contemporaries among the students across the year groups during Mary’s five year training included Elisabeth Benjamin (1908–1999), Jessica Albery (1908–1991), Jane Drew (1911–1996), Judith Ledeboer (1901–1990),7 and Margaret Justin Blanco White (1911–2001). The cohort also included Max Lock (1909–1988) and John Brandon-Jones (1908–1999). Many of these fellow students were to become life-long friends.

During this period, in the UK, Europe and beyond, architecture was regarded as a thoroughly male profession and when women succeeded, which was rare, it was believed that their designs should do nothing to undermine their femininity. In Germany, at the Bauhaus under Walter Gropius, women were barred from architecture courses and confined to textiles and weaving.8 In England, the social expectations of women in practice are illustrated by the experience of Elisabeth Scott, who had become the first woman to qualify at the AA in 1924 and who went on to win the highly competitive commission to design the new Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon. Both Mary Crowley and Judith Ledeboer admired Scott who in turn ensured that they both had the opportunity to work alongside her on this major theatre project.9 Scott had to tolerate suggestions made in the press at the time that as a woman she could not really have been responsible for a theatre design regarded as, strong, direct and bold: the implication being that a man must have been responsible for the main decisions. A journalist commented, ‘it seemed almost incredible that she could have produced something that was so extremely opposed to her own personality’.10 The landscape designer Geoffrey Jellicoe (1900–1996) recalled that ‘Elisabeth was gentle, unassuming, determined, and with a personal integrity that acknowledged her associates’ help’.11 This judgement implies personality traits in common with Mary who displayed similar characteristics throughout her life. It could well underline how, to succeed in this field, women were forced by social and cultural expectations to tread a very fine line with regard to their gender identity. How far this wider climate impacted on Mary’s career as a female architect needs consideration in the context of her career, dominated by domestic projects and designing environments principally used by women and children. The field of education, whose professional body was predominantly female, provided a form of architectural practice more acceptable to clients and the general public than more general architectural commissions.

At the AA, Mary proved to be a very able student from the start, abler than the majority of her male counterparts studying exactly the same syllabus. It became the norm for her to be awarded merits and distinctions for coursework. She gained merits for five subjects taken during her first term in the autumn of 1927: only her model let her down. Best in year was achieved by fellow student Edward Wilfred Nassau Mallows (1905–1998).12 Possibly this arose from Mary not sitting her first year exams: the records showing her ‘away’, perhaps owing to illness, which must have reduced her final marks.13

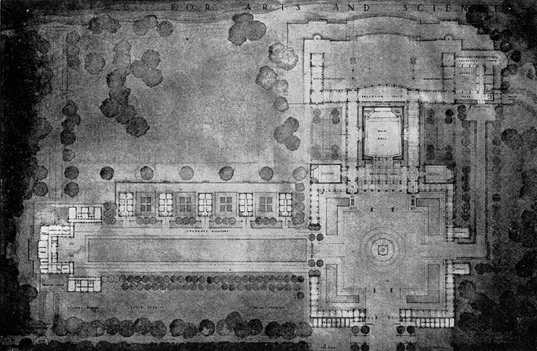

2.2 An Educational Centre for Arts and Sciences by Mary Crowley, fifth year. Architectural Association Archives 16

During her second year, Mary achieved highest marks in the first term, studying Greek architecture and Greek and Roman History.14 John Brandon-Jones joined Mary’s cohort having spent some time in practice as a 17-year-old assistant to the office of the architect Oswald P. Milne, and soon proved to be a student of distinction. In the first term of the third year, the syllabus included a design for the construction of a school hall and Mary, not surprisingly, gained merits for this work. This laid the ground for her final year thesis, ‘An Educational Centre for Arts and Sciences’ (Fig. 2.2). Mary’s thesis was one of only four to pass with distinction and through this she became the first female architect ever to win the end of year first prize.15

It was a stimulating period for study at the AA when its syllabus was beginning to be influenced by Dutch and Scandinavian developments, certainly reflected in Mary’s travels as well as in her life long architectural philosophy. At this time the school became the first to receive recognition of its diploma for full professional qualification. Teaching at the AA during these years were the landscape architect Geoffrey Jellicoe (1900–1996),17 Howard Robertson (1888–1963),18 and Frank Yerbury (1885–1970).19 Robertson became principal of the School in 1926 and later director of education from 1929 to 1935. Yerbury was the School administrator until he resigned in 1937 to spend more time developing the Building Centre, a concept that he had nurtured at the AA.20 Yerbury was also a talented photographer with a special interest in documenting the Modernist movement in Europe. As such he profoundly influenced the direction taken by the AA during the 1930s and became the prime source of information on and contact with the contemporary architecture and leading architects in the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden.

2.3 Studio portrait of Mary as student at the AA. IOE Archives, ME/A/1/11

At this time, Mary was living with her parents and she commuted daily from Welwyn Garden City to King’s Cross. In her spare time she taught herself to drive the family Jowett.

She was an excellent and hard-working student as her marks indicate. Yet, though pleased to be pursuing training that fitted her talents well, she was also somewhat troubled about the overall point and purpose of her life and occasionally a longed for simplicity spilled into her diary entries.

Why this striving after effort, this doubting, this everlasting sense of just missing things nearly in our grasp, this feeling of never getting any further? Why can’t we be content to accept one day after another for what it brings, to notice how the clouds pass; how the flowers suck in the sun, letting it pass through them, transform them, smell good smells; and above all to enjoy being with others, noticing things they like, careful never to hurt them.

This intense reflection on time and materiality and the challenge of being alive in the present may have been influenced by Zilliacus who became fascinated by, and sympathetic to psychotherapy in his educational projects. But it also reflects a restlessness experienced by other highly educated women of the time from Quaker backgrounds. A contemporary, Francesca Wilson (1888–1981) struck a similar tone as she reflected on her motivation to carry out relief work after the First World War

I wanted foreign travel, adventure, romance, the unknown … The main force driving me … has been first of all a desire for adventure and a new experience and later on a longing for an activity that would take me out of myself, out of the all too bookish world I had lived in.21

Students enjoyed a good social life and a great deal of fun at the AA as many contemporary accounts testify.22 There was serious work but this was accompanied by development of strong and lasting friendships in an atmosphere of laughter and music provided by a gramophone in one of the studios. Mary, who read avidly, at this time was consuming Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture and Bruno Taut’s Modern Architecture as well as discovering the sculpture of Carl Milles (1875–1955), whose work first came to an international audience when it was exhibited at the Tate Gallery in 1927. Meeting Milles and his wife Olga at their home and garden in Stockholm in the summer of 1930 was to have a profound influence on Mary as we shall see.23

The annual AA pantomime was an artistic and dramatic highlight, taken very seriously by staff and students as images preserved from the time illustrate. Mary was invited to participate at the end of the first term of her second year of study and took a role again in the next two productions. In Mary’s case, this demanded a dramatic transformation of character and offered the opportunity to reflect deeply on the way that she presented herself in the world and how others saw her.

Last week, I made myself into somebody else, someone with sleek hair, with a curl under each ear, with painted cheeks and arched eyebrows and ear rings. She wasn’t me; she was someone they seemed to think was attractive and someone who could twist people around her little finger, perhaps. They told me I ought always to look like that. Yes, perhaps if I chose I could come out of myself and act like that rather dazzling earringy person and not be mistaken for ‘M’ and ‘pure’! But if I do not choose, that is that. It’s interesting, perhaps, to know that I could if I wished.24

This reflection is revealing given the usual reserve and self-effacement that those who knew her throughout her life recalled. In her own way she was an attractive woman as evidenced by the many male admirers she had to deal with during these years. In addition to the ongoing relationship with Laurin Zilliacus, she received the attentions of Geoffrey Jellicoe, John Brandon-Jones and Ernő Goldfinger (1902–1987) who were perhaps each able to see in their different ways that dazzling person ‘lurking within’.25

2.4 Mary Crowley appearing in the annual AA pantomime, 1928. Architectural Association Archives

The AA was a hub of activity attracting architecture students from across the UK and there were regular opportunities to socialize with visiting students from other cities. On one such occasion Mary dined with visitors, enjoying conversation with the AA Librarian and architect Hope Bagenal (1888–1979)26 after which taxis were taken to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) galleries where the crowd danced from 1.00am until 5.20am, ‘the best of our dances being of course, that there are more men than women!’27 And there were exhibitions to attend such as the Dutch Art Exhibition at Burlington House in January 1929 where Mary took note of the colours and light and of Van Gogh’s ‘relentless brilliance of colour and movement’.28

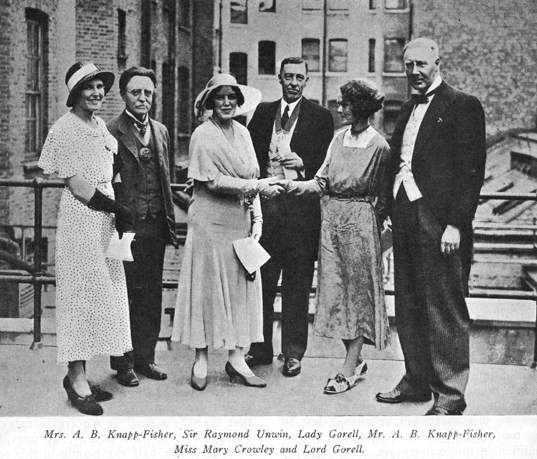

Her views on the training she received were mixed. Mary joined the AA at a time of international flux and excitement at major changes in approaches to architecture while the syllabus she encountered was still organized along the lines of the classical Beaux-Arts model. Her early years of study coincided with a growing interest in Continental Modernism especially after the first English translation of Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture (Vers une Architecture) was published in 1927. This book was widely reviewed and discussed causing a ferment of interest and diversity of reactions.29 Such a context explains Mary’s critical assessment of the education she received at the AA. She was appreciative of the teaching and the atmosphere but with hindsight was critical of the rather conservative and traditional approaches to training, feeling a lot more could have been achieved and a richer education encountered, as occurred following a ‘revolution’ at the school shortly before the war. The several prizes, awards and medals received for her work she lightly dismissed as inevitable ‘if you simply got on with things’, an attitude quite in character as she was known for a continuing reluctance to acknowledge her own talents and real achievements. One of her awards was earned in her final year: the French medal from the ‘Société des Architectes’.31

2.5 Mary Crowley receiving the French medal from the ‘Societe des Architects’, July 1932.30 Architectural Association Archives

Her final thesis, an educational centre for a town of 25,000 inhabitants won a distinction. The site chosen was nearby the recreation grounds at Welwyn Garden City, near her family home. The scheme was envisaged as an extension on a larger scale of such experiments as those she was familiar with through her father’s career, and she mentioned both the school system of Gary, Indiana that Ralph Crowley had visited in 1913 as well as the recently constructed Sawston Village College in Cambridgeshire (1927–1930), the first of Henry Morris’s celebrated series of colleges and ‘the most prophetic expression of what a community school might mean’.32 In Mary’s scheme, the buildings were to include a hall for meetings, concerts and theatricals with full-scale film projection facilities. The hall had removable seats that could be stored under the stage to facilitate dancing and other entertainments while folding French doors opened out onto a terrace and court. It contained a small public library ‘to be open all day to the public for lending and reference’ near to the students’ entrance and ‘divided into bays with glass partitions’. There was to be a special children’s room within the library ‘with clear-storey lighting over covered ways’. The plan contained handicraft rooms; workshops equipped for carpentry, metal work, art work as required; gymnasium and changing rooms for both sexes with shower baths; lecture rooms and staff rooms; first aid and music rooms; and classrooms for housewifery were to be adjacent to an infant welfare centre ‘so that the rooms can be used for afternoon classes for mothers as well as for evening classes.’ The welfare centre was to have a cross ventilated waiting room with a South West aspect and French doors out to gardens. It would have its own entrance complete with pram shelters and a basement for storing mechanical equipment.33

It was assumed in the plan that there would be an adjacent ‘post-primary’ school for boys and girls and that the building would be available for use of this school during the day and used for adult education in the evening. The notion that education and welfare might be mutually supported in a progressive educational environment characterized by functionality was familiar in the discourses Mary knew through her father’s networks. An intergenerational space embracing the community for education, instruction and entertainment was essentially a statement about social justice and the building of a healthy and knowledgeable citizenry. Mary’s thesis drew more from educational progressivism than from aesthetics and demonstrated her growing understanding of the potential for an educationally informed architecture.

STUDY TOURS

Holland, Easter 1930

Holland was attractive at this time for those keen to see modernist developments in housing and public buildings. The old, set alongside the new, provided a rich and varied pallette. Mary and her family were not alone in admiring the domestic and public buildings of the Dutch towns and cities: the architect Norah Aiton (1904–1989) also knew Holland well. By her mid-twenties, Aiton had visited that country at least five times (in 1919, 1920, 1924, 1925, and 1927/8), spending one undergraduate summer working in the offices of P. J. H. Cuypers.34 Mary travelled with her father to Holland over ten days at Easter in 1930. She may have prepared for her journey to Holland by reading A Wanderer in Holland by Edward Verrall Lucas (1868–1938) whose work, as a fellow Quaker, would have been known to the Crowley family.

On this occasion, they lodged at The American Hotel in Amsterdam, a noteable building by the architect Kromhout, where by chance Frank R. Yerbury (1885–1970) was also staying, preparing his second book of photographs on modern Dutch architecture.35 Like Mary and her contemporaries at the AA, Yerbury was at this time enthusiastically turning to Scandinavia and to Holland for examples of the emerging Modernist style.36 On this trip, Mary and her father accompanied Yerbury to view some significant new developments of housing schemes on the outskirts of Amsterdam. Yerbury also arranged a meeting at Volendam between Mary, her father and a group of other architects including E. R. Jarrett from the AA who were also intent on visiting and viewing Dutch architectural innovation. Mary recorded amusement in her diary at the contrast between the traditional architectural surroundings of their cosy hotel and the collective interests of the group meeting there: ‘I like the way we come to a remote fishing village away from everywhere in Holland and find six architects in the same inn!’37

Travelling by bus, the group went to see the ‘new architecture’ at Hilversum. Hilversum, in 1930, was developing fast due to the influence of the recently appointed city architect Willem Marinus Dudok (1884–1974). Several schools were under construction as was the Town Hall, later regarded as Dudok’s finest work.38 Mary may have seen Dudok’s Rembrandt School, completed in 1920. Here was an early effort to humanize and de-institutionalize the school using traditional materials with close attention to scale and the provision of good quality courtyard interiors. If the group had entered the school they would have noted the series of recessed alcoves along the corridor to provide spaces for small group work and she would have enjoyed the internal exposed dark brickwork and colourful plastered walls.

In the neighbouring housing the brickwork and clean lines appealed, ‘the houses seem rational and reasonable and a lot of them very attractive’.39 But there was more than a straightforward attention to the functional. Unlike the housing developments that were familiar in England, here Mary observed that the ‘details are more carefully thought out; there is better woodwork and more space sacrificed so that the architect can enjoy himself a little’. Given these remarks, we can see that Mary was not convinced by Le Corbusier’s diatribe on style and rational morality. Rather, the social housing in Hilversum may have reminded Mary of her own family’s commitment to the Garden City movement in England during her childhood. Here, she found good examples of municipal housing grouped around garden and communal areas.

In contrast to the modernist architecture of Dudok’s Hilversum, Mary had a clear fondness for the traditional domestic architecture and landscape found, for example in the small town of Middelburg which became one of her favourite places to stay in Holland. She returned to the same hotel at Middelburg several times during this period.40 Always observing and recording the features of her immediate environment, we are able to glimpse what she valued and these were often objects or designs offering aesthetic pleasure. In her travel journal, for example, she describes the interior of one of the hotel toilets which was long and narrow and has a ‘quite wonderful collection of blue and white tiles about 4 feet up the walls. Hardly any two are alike and every thinkable bird or beast is painted on them. It is a little museum in itself.’ Later, as a school architect, she and her partner David would delight in incorporating blue and white ceramic tiles by the ceramicist Dorothy Annan into Woodside school at Amersham, each one different from the other so that the eyes of children might be drawn to them in curiosity. Annan produced tiles decorated with birds and other small creatures for the splashboard of classroom workspace sinks as well as for water fountains in the school.41

She enjoyed enormously what Middelburg had to offer, a large prosperous town full of quaint squares where she took time to note in her diary the attractive scene of young children, closely observed, inhabiting the squares and playing informally.

In the centre of the square is a great group of chestnut trees just come out into leaf and having that new freshness about them and yesterday there were lots of schoolchildren playing in groups, pretending to have gym – classes, or hopscotch or resting round the stone group, or merely chatting. Here and there were groups of boys of 11 or 12 with their bicycles lounging in a self-conscious way smoking cigarettes – one even had a cigarette holder. Occasionally a bicycle would dash around the square …

Her diary paints images of ‘an absolute peace which is not a dead and forgotten peace but one which is alive’.42

Here, Mary reflected on her enjoyment of A Wanderer in Holland, particularly the chapter on Middelburg: ‘As E V Lucas says, everything here is curved and rounded. There is no sharpness anywhere. All the town is planned on circular shapes.’ Even the entrance to the W.C. in the hotel, she noticed, was curved. She appreciated the many town squares and the most perfect square of all was ‘the one with the 1882 anchor house’ where she spent the morning sketching.

At The Haague, she was impressed by the recently constructed Christian Science Church by Hendrik Petrus Berlage (1856–1934), a brick building somewhat in the style of the Hilversum Town Hall. However, since she was traveling with her father, thoughts of visiting and observing environments designed for education were never far away and while staying at a vegetarian hotel in Delft, Mary and her father visited local schools.

They discovered two ‘extraordinarily attractive schools’ near the gasworks. One a kindergarten, very simple but delightfully worked out, built in a grey coloured brick with blue paintwork and another ‘delightful one, larger and built around a court, with shiny tiled roofs and orange tiles and white coloured windows’. As was to become a life-long practice, Mary sketched these in her notebook.

The AA Study Tour in Scandinavia, July 1930

it was really rather a landmark.43

Before the early 1920s, the academic and architectural interests of students attending courses at the AA had been guided towards developments in Dutch design but this began to shift towards an interest in Scandinavia where significant relationships between the AA and the Nordic countries were developing. Sweden’s Crown Prince Gustav Adolf VI (1882–1973) was interested in modern developments in architecture and in 1923 visited the AA, touring the studios, inspecting the curriculum and looking at students’ work. From this visit, there developed a joint commitment to bring together a more formal exchange between the work of the AA and Swedish architects. Frank Yerbury, then secretary of the AA was also a council member of the Anglo-Swedish society. Yerbury took up the invitation and within a few months had visited Sweden to make contacts and to make arrangements for a major exhibition of Swedish architectural work to be hosted by the AA. While in Stockholm, Yerbury saw the recently completed City Hall (Stadhus) which he declared to be ‘perhaps the finest modern building in the world … a veritable exhibition of a modern school of craftsmanship’.44 The building, designed by Ragnar Östberg (1866–1945) was built on a prominent site overlooking Riddarfjärden between 1911 and 1923 and was a remarkable achievement in blending renaissance and modern art forms.

When the Swedish exhibition eventually opened at the London RIBA galleries in May 1924, unsurprisingly, a model of the Stockholm city hall formed the centrepiece. All this interest and exchange activity stimulated further commitments and the destination of the annual AA study tour the following year, 1925, became Stockholm. Yerbury’s recent contacts ensured that on embarking at the docks, the group was met by Östberg in person, who warmly greeted the students and personally guided them around his spectacular building.

Not only was London coming to appreciate Scandinavian Modernism, but its influence was also reaching across the Atlantic. By this time, the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen (1873–1950) had settled in America following his success in an architectural competition and in 1928, his old friend Ragnar Östberg was also unsuccessfully courted by various American schools of architecture to join them as visiting professor.45

In 1929, the AA hosted an exhibition showcasing the talents of the young mosaic artist Einar Forseth (1892–1988) who had been responsible for the magnificent decoration of the Gold Hall which was embellished from floor to ceiling in gold mosaic and glass depicting important events and people in Swedish history. The Swedish ambassador opened the exhibition and the Crown Prince made a further visit to London to see it. Thus, during Mary’s years as a student at the AA, Scandinavian architecture and prominent architects were becoming known as leading exponents of a distinctive form of Modernism rooted in the Arts and Crafts tradition.46

On completing her third year of studies, Mary Crowley was able to participate in the now annual Scandinavian study tour in the company of her tutors and fellow students. This tour in July 1930 coincided with the Stockholm Exhibition.47 The journey and the many significant meetings and observations it enabled are described in detail in Mary’s diaries and the experience was evidently not only great fun but in many ways was an education in itself. In spite of the opportunity to visit the Stockholm Exhibition and to see so much that was modern and new in architecture, for Mary, the highlight of the tour was visiting and meeting the sculptor Carl Milles at his home at Lidingö, an island in the inner Stockholm archipelago. This brought vividly to her the significance of sculpture as an art form and reinforced her enchantment with Swedish art and sensibilities.

The tour which was arranged to spend two days in Gothenburg, five in Stockholm and four in Copenhagen attracted a record number of participants from the AA. A group of 95 third and fourth year students and teachers left St. Pancras station on the evening of 16 July and travelled to Sweden on the Britannia from Harwich. The weather was fine and a great deal of fun was had on board.

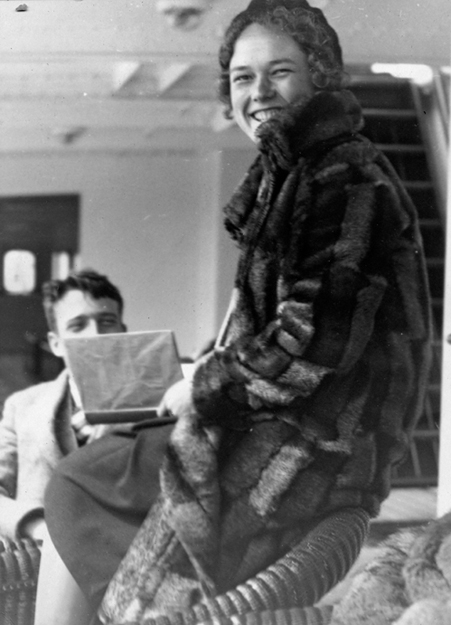

2.6 Mary Crowley – dressed for all weathers on board the Britannia, en route to Sweden, July 1930. IOE Archives, ME/A/3/2

‘It felt like a strange AA dream, seeing people we know all over the ship chatting and wandering about.’ Yerbury and Jarrett organized the entertainment with the help of a gramophone set up in one of the small coffee saloons on this comfortable ship ‘and we starting dancing both inside and out and leant over the railing watching the white streams of water go by’. On the voyage Mary found it almost impossible to keep up her regular diary entries because ‘women, when we get together can’t help talking’.

On arrival, they first visited Gothenburg from where they took a tour by charabancs and cars and on the way took a look at one of the ‘new’ schools which Mary noted, ‘had some very nice bits and a jolly, simply treated corridor off which the classrooms led, and a covered way and a court’. But the brickwork was disappointing and not nearly as well done as had been noticed in Holland. It had, ‘a harder sort of texture, with less variation … but every detail is perfected and there is a feeling of daintiness and simplicity, with just the right amount of detail in just the right places’.48

Eventually the large group arrived in Stockholm after traveling by overnight train and the gender imbalance in such cramped conditions was noted. The train had ‘bunks in three layers (for) the whole party. Two carriages of females among a swarm of males.’ The presence of women in the group was misunderstood by the local press but reports of the visit increased the visibility of the visitors in the city. ‘There had been so many photos of us in the local papers (sometimes being called the English architects and their wives) that we were constantly recognized.’ Stockholm was, ‘a dream too quickly dreamt’ and ‘one of the most lovely places to stay at and explore’. There were site visits by day and parties by night. The Stockholm exhibition was open to the visitors who witnessed through it a significant moment in the Scandinavian contribution to Modernism. ‘What appealed was the simplicity, and straightforwardness. That influence goes right through architecture even to the washing up bowl and that influence went through me.’49

A range of public buildings and institutions were viewed including a Masonic Children’s Home designed by Hakon Ahlberg at Blackeberg in the outskirts of Stockholm (Fig. 2.7). This building had attracted the attention of scholars at the AA during Mary’s years there. Howard Robertson had brought the building to students’ attention through a piece he had written entitled ‘Sensitive Simplicity’ for The Architect and Building News where he commented on the historical neglect of taking seriously buildings for the youngest members of society.

The result has frequently been the production of buildings designed unsympathetically, bald and institutional in character … and considered from the point of view of satisfying the demands of the grown ups who build and direct them. The idea of looking at design from the child’s point of view, does not seem to have been put forward with sufficient conviction to be a factor in design.50

Taking children seriously in the design of their buildings was to be the subject of Mary Crowley’s life, and the article by Robertson suggests some sympathy with this point of view that Mary had encountered at the AA.

2.7 Masonic Children’s Home designed by Hakon Ahlberg at Blackeberg. IOE Archives, ME/A/3/3

This building was noted for its welcoming character and lack of institutional atmosphere which at the time was most unusual in a building of this type, pointing the way to a more humane architecture for the young and emotionally vulnerable.

At the City Hall (Stadshus), as was now the tradition, the group met the architect Ragnar Östberg (1866–1945) who proudly showed them his building on two separate occasions. They were hosted by the Mayor of the Town Council and enjoyed tea in the magnificent Gold Hall (Gyllene Salen) at his invitation.

The Gyllene Salen was a seminal part of the building that was attracting much commentary and critique at this time. It is therefore unsurprising, considering the impact then and since that Mary spent time reflecting on her own impressions of this extraordinary achievement in art and design. In her travel journal she vividly recalled the procession through the building towards this supreme space.

… with the glorious woven curtains behind which you know the Gold Hall is to come. Then through the curtains and great double doors until you are faced with the great length of the Golden Hall, its walls entirely mosaiced with gold and the great figure facing you at the far end. And the light coming slanting in on either side through the tall windows … the long low tables and seats and the shining floor.

The great figure Mary mentioned was a mosaic depicting a Swedish Queen and the form of her representation generated debate at the time as some critics did not appreciate her rather masculine and exotic Byzantine features that seemed at odds in a northern European capital city.

Mary found herself attracted back to the Stadshus and its surrounds where she returned to wander alone each day to draw or just sit about. She found more and more secrets within and about the spaces as extracts from her travel journal illustrate.

At every step there is something new and wonderfully quaint and beautiful and yet the simplicity is never for a moment broken.

At other times I would go and sit on the steps by the water and watch the ships coming in, and talk (with the others) about what we thought of Stockholm, and have one more look at a favourite bit, or show someone the mischievous head that spouts water into the pond up by the white figures to discuss why, with everything just not on any axis, and happening just because it couldn’t help it, the place was one whole with no jar anywhere.

Uncompromising in its romanticism, for Mary the building worked as an aesthetic achievement and a work of high art.

the whole thing happening as if it had grown of itself and hadn’t been able to help it. At first it seems very simple and plain and then you begin wondering when you will ever stop finding new and lovely bits of detail.

Inside the Blue Court there is a soft silence and a soft light, after the brilliant sunshine outside and somewhere there is a sound of a fountain.

However, according to her own account the most important and significant part of the tour was neither the Stockholm Exhibition nor the City Hall but the day spent at the extraordinary home of the sculptor Carl Milles and his wife, the portrait artist Olga Milles. Through this account we glimpse how important for Mary was artistic expression through sculpture in its essential beauty but also in the tension held through its presence in the landscape.

The thing that will sum up all Sweden and which has to me been worth coming over for alone if for nothing else is the morning we had with Carl Milles, in his house and garden. There is a man who to me sums up all the beauty of sculpture which can stir me up more than anything, who lives among his works on a hill above the waters in a house and garden different from any I have seen, which I shall remember always as being brilliant in the sunshine, with its terraces, patterned with girdled squares and played over by the shadows of willow trees and statues; the pond with the great four figured fountain.

Milles had bought a plot of land on the island of Lidingö, in 1906. There, he had a house and studio built looking out over the waters towards the city.51 By the time of Mary’s visit in July 1930, Milles had won acclaim nationally and internationally and the house and garden terraces held some magnificent work both complete and in progress. It also held some gems such as the kitchen cabinet in the breakfast nook decorated by Olga and containing the couple’s pewter and ceramic collection. With motives borrowed from Dutch Deflt tiles, depicting young children, each one different from the next, Mary’s eye would have been drawn to the simplicity of the blue strokes as they had been to the tiles she loved in Middelburg.

The 1920s saw Milles produce some of the most important art works in Sweden while in post as professor at the Royal Art Academy in Stockholm.52 In the large studio, the summer visitors would have been able to view the colossal Poseidon in progress, surrounded by scaffolding. The Poseidon fountain was eventually placed at Götaplatsen in Gothenburg in 1931 as part of the city’s 300 years celebrations.

On this occasion, when the rest of the group had left, Mary wandered down to the garden terrace inspired by Mediterranean landscapes, and in the bright sunshine became absorbed in drawing the sculptures. She explained in an interview much later in life how she was entranced by Milles’ work, simply stating ‘and sculpture got me, you see’.53

Milles, noticing her concentrated interest and delight, approached her from the terrace steps and called out inviting her to stay and draw for as long as she wished. Mary felt like she was inhabiting ‘some other world’ among the statues and fountains which she perceived ‘were all alive in the secret loveliness and unexplainable beauty of the place’. The bronze sculptures Mary would have seen were Milles’ early work.54 Nevertheless, visiting Millesgarden today it is possible to see the power of the sculpted forms set in the Romanesque terraces dancing in the waters and poised in the lush gardens that worked their spells on Mary. The sculptor’s favourite work was reported to be Water Nymph Astride a Dolphin made in 1918 whose beauty of form and captured energy she would have admired. On the terrace was Milles’ first of many sculpture fountains made in 1916 and commissioned by Prince Eugen in bronze and black granite. The creatures taking form in the gardens were childlike and whimsical, simple observations of life drawn in marvellous postures of ecstasy or play.

Milles had become fascinated by classical Roman and Greek architecture and sculpture having lived for a short time in Italy to improve his health. Mary was impressed by the artist who she evidently had looked forward to meeting with some anticipation. She was not disappointed.

2.8 Carl Milles helping a student in his garden, July 1930. IOE Archives, ME/A/3/2

As for Milles himself – I’ve not said anything about him because I don’t know how to describe him or where to start. All I know is that he is a living part of all the work he has done, and never have I seen anyone who so entirely realized every expectation and fitted in so perfectly with everything. As soon as you see him you feel you are in the presence of someone who can quietly see beyond things, with a quiet and perfect understanding, who must live among beautiful things, so that the whole of his home and garden has become part of him and his work. With a generosity and a perfectness of life so that you know immediately you can ‘slip in’ and once you are there that you are no longer a visitor, but become part of the place. A slow, evenly monotonous tone, and never much lively change of expression in his face, but just the grey eyes which are slightly closed as if he were looking beyond and through, with the kind wrinkles at the end of them. His hair is grey but he has a young face (he is just over 60) as if he were only about 50. He is a medium build and had on a white overall all the time. His hands are strong and firm fingered and just as you would have expected them to be.

The artist, who was younger in years than Mary had imagined, and his wife Olga invited Mary to lunch with them on the terrace. Perhaps the conversation turned to architectural education and new radical approaches that were beginning to be being practiced in Europe and in America. It is likely they discussed the Stockholm Exhibition and Milles’ recent visit to the USA prompting his decision to leave Stockholm and his beloved garden to take up residence in a house and studio that was being completed for him and Olga next door to the house of Eliel Saarinen at the Cranbrook Foundation. The generous hospitality that Mary enjoyed was a trait that students later recalled of Milles when at Cranbrook he regularly invited them into his home, recounted his experiences as an artist and lectured them about his collections.55

Milles had visited the Cranbrook Foundation at Bloomfields north of Detroit in November 1929 at the invitation of George Booth who was searching for a permanent sculptor in residence.56 Milles had been recommended to Booth by his old friend Eliel Saarinen. Cranbrook was an extraordinary settlement built around the family home of this wealthy benefactor with the intention of bringing together the arts and crafts with the best of modern architecture. It is likely that the possibilities offered by partnering the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen within this new venture formed part of the conversation over lunch that day.57 Originally, the sculptor in residence at Cranbrook was the Hungarian and friend of Saarinen, Geza Maroti who completed an impressive stone carved mural for the library at Cranbrook Boys School but who found that he and his wife could not settle in America. The following year, Carl and Olga Milles left their beautiful home behind and moved to Cranbrook. There Milles became resident artist and head of the department of sculpture for a period of twenty years before returning to Stockholm a few years before his death in 1955.

What did Mary see in Milles’ garden that so caught her eye and engaged her spirit? The essential art form of sculpture and its harmonious integration with architecture and landscape may have reminded her of the harmony she had witnessed once watching seagulls fly out over a headland. ‘… their workmanship is perfect. There you have colour and light and shade, movement and rhythm and form and silence. Seagulls flying in the sun are music, poetry, dancing and drawing and sculpture all in one.’58

Many years later she would visit Cranbrook with David Medd and witness the results of this extraordinary project which saw a unique flourishing of the creative arts in conjunction with new forms and materials and where schools, decorated inside and out with the finest detail expressed fully the potential in uniting all of the arts in what was considered to be a humanizing architecture.59

Denmark: Copenhagen

Copenhagen and Denmark are solid and Germanic and heavy without much sense of humour after Stockholm and the Swedes.

In Copenhagen, the group of AA students and their teachers continued to find time for sight seeing, pleasure and relaxation but there was also the overriding purpose which was to see as much modern work as possible under the direction and supervision of the local architects responsible. On this occasion, housing developments, schools, churches and a crematorium were visited.

The 1930s and 1940s saw many new social housing schemes developed in the villages on the outskirts of Copenhagen, effectively expanding the city. The several housing schemes that were visited were in the main four to five story blocks and they were appreciated for their modernity but there was a human element missing that for Mary was becoming so important. She began to define what this was as she reflected in her journal. In Denmark,

there was none of the unique fairy touch of Sweden. Very solemn, massive, useful and no whimsicality anywhere – very like the Danish architects themselves, I fancy. The crematorium was a horror and I don’t want to see that again. In case I died in Copenhagen I made them promise not to have me cremated.

The opportunity arose to visit a school under construction in the company of the architect responsible and Mary, already confident in her views on colour, was not impressed. ‘The school was built up around a covered court in three stories, a different colour for each story, each just slightly more terrible than the last.’ We can see in this remark the beginnings of an appreciation that colour was a mechanism for integrating all elements of design in a school towards it working as a whole educational environment.

At the time of their visit, the now famous Grundtvig Church in the northern suburb of Bispebjerg was under construction and Mary was introduced to the architect, Peder Vilhelm Jensen-Klint who died later that same year. Mary admired the brickwork and monumental modernist construction. She returned to see the finished church much later in life, in 1997.60

Before the end of their time in and around Copenhagen, the group enjoyed the summer weather, sight seeing, bathing and rowing, and visiting the brewery. At Elsinor and the Kronburg castle, they scrambled up the tower and into the long galleries and halls enjoying architecture that according to Mary was ‘equivalent to some of the best modern stuff we’ve seen’. Wherever there was a suitable lake, Mary would enjoy swimming. At Hillerod they spent time relaxing and drawing each other while in the evening they socialized, ‘about 20 of us ate at one long table (and later) tried to see “Metropolis” but got there too late’.61

The study tour ended on 30 July when Mary and her fellow students and teachers left Esjborg, bound for Harwich, in good spirits. It was time to reflect on a month of discovery and deep learning. Before the end of the journey, Mary recorded in her journal some of her emerging reflections on the relationship between nature, experience and development and what appeared to her to be that force or energy which connects subject and object in the process of creation. This became her educational philosophy and the material and environmental conditions to support such a process of creation were what she came to strive for in her later professional life. It is interesting to see how she placed the experience of the child at the heart of that philosophy.

Development of the fullness of life is the process of becoming expert by experience. No right to attainment except by experiment – trial and error. All experience has a subject-object relationship. The child starts with confusion, but gradually we become an ordered and articulate whole, the subject and object relationship constantly expanding and contracting and eventually almost merging. The craftsman begins with uncertain relationship to his material which eventually yields and becomes an expression of subject … a person is most a person when he has creative power of force (for example) motherhood, craftsmanship. In this function of creativity there is a degree of inapproachability, of mystery – awe. This is also found in the order of nature.

Other Journeys

Aligning craftsmanship with development of identity and the power of creativity gives us some insight into Mary’s developing philosophy of education that was to find full expression in later years as an architect designing schools fit for children’s growth and development. She no doubt was aware of the Bauhaus movement during the years of her study and was soon to meet with those who practiced along these lines when she visited Germany. But first in the spring of 1931 travelling once again with her mother and father in Italy, Mary visited Florence and Siena. The Italian spring holiday, while predominantly intended for sight seeing and relaxation, was peppered throughout with opportunities to develop her prospects as an architect. She, as yet, had no clear focus on any particular type of building and was interested in most types. An introduction from Geoffrey Jellicoe allowed them to visit villas by well known architects and Mary noted the ‘lovely tones of yellow warm brickwork’ of Tuscan churches.62 As usual, she made drawings and rubbings of features she admired. At Lausanne, she came across ‘some good brick decoration above a doorway – and made a rubbing’ and recorded some words of Yeats in her diary.

The wrong of unshapely things is a wrong too great to be told;

I hunger to build them anew and sit on a green knoll apart,

With the earth and the sky and the water, remade, like a casket of gold

For my dreams of your image that blossoms a rose in the deeps of my heart.63

Brickwork, particularly the possibilities of colour and tone, always drew Mary’s interest and held a deep attraction for her at this time. Often, in her notebooks we find reference to her appreciation of the aesthetics of brick, the ‘warm’ tones observed during her travels. For example, at Stratford-upon-Avon, where Mary visited Elisabeth Scott’s newly constructed theatre, she commented on a certain lack of appeal in the brick detailing, finding the brickwork that she had encountered in Europe on her travels more to her taste. Of Scott’s new theatre, she imagined other possibilities and suggested, ‘there ought to have been a smaller course – a Flemish brick would have given a much better scale and the ornamentation is too monotonous (there being insufficient) contrast between plain and flattened brick.’

She had much to say about the distinctive tone of the brickwork found in the cottages thereabouts. At Bourton-on-the-Water she appreciated the loveliness of ‘the local yellow stone that looks beautiful with dark blue paintwork’. In contrast she found a dreary solidity in some of the midlands coal-mining towns, ‘oppressed by the heaviness of the atmosphere, half-asleep. No colour or brilliancy, just existence in a dilapidated ugliness’. She criticized the housing at Ironbridge, for example as no more than a ‘sordid, poverty-struck hideousness’. The significance of colour, then, leads us to see how Mary’s appreciation of architecture was tempered by a sense of human relationships engendered by the tones encountered. Colour became an abiding interest of her partner and husband David Medd, but we can see in Mary’s early life how colour was also brought into that important relationship by Mary’s own perspective.

Mary’s youth, physical energy, and adventurous nature is reflected in certain diary entries during these years. However, during holidays taken with her parents she occasionally betrays restlessness. Taking early morning beach walks while staying on the Brittany coast in August 1931, her impressions display certain feelings of frustration.

Up and ‘away across the silvery grey sands … wandered to where a few carts had come in with eggs and veg … what I wanted at that moment was a horse so that I could get on him and gallop away towards the horizon …’

But the pressing beauty of the landscape and romance of the architecture was inescapable. Of Mont St Michel, she wrote,

Of course it is all sentimentality and probably would be better left undescribed. But then the Mont is romantic and sentimental if you will. Why not? Its beauty is there nevertheless, and impresses itself on the memory; must be stored and remembered. And one knows it is good to see and to remember and to be part of these things.

While travelling and holidaying Mary read avidly. There was romance in her choice of literature – The Fountain, by Charles Morgan – ‘the finding of reality through inner meditation’ and ‘a beautiful love story’, All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West, the latter read perhaps reflecting Mary’s thoughts on a woman’s place in society which may have led her to question her own ability to control her destiny. Other reading included: The Golden Arrow by Mary Webb; Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover; Chesterton’s The Return of Don Quixote; and The Life of Gaudier Brzeska by H. S. Ede. Most of these were recently published and important works, the latter recognizing the life of an extraordinary artist and sculptor who had died as a young soldier in the First World War.64

At the end of this summer of travel at the age of 24, she mused on life’s apparent beauty and fragility as if she were always held by ‘a thin veil from horror, and suffering and evil ugliness’. She was becoming increasingly aware and disturbed by reports of the ongoing political polarization in Europe. She was also coming to see the meaning of her life as fulfilling its potential for spreading beauty more widely and leaving a legacy of richness.

Sometimes, perhaps, it will be made plain how it can be possible to spread what is beautiful and of lasting importance working with clear and definite aim, knowing and recognizing the work that is there for you to do, which you are capable and willing to do. But now, though everything is undefined and unknown to us, we can at least let all the beauty we have seen and lived in, live on continually in us. Again and again I say there is no excuse for any grumbling grousy attitude just because one is not strong enough to catch more than small glimpses of the true meanings of life.

If only we could retain the strength and the quiet powers of all the great stretches of country we have known, with its rhythm and movement and changing lights and colours, but always the silence and the still reverence and quiet brooding of the hills and skies.

The Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments of 1932–1934 met in Geneva and Mary’s diary entries record a growing consciousness of two things: her own privileged life of family, education, opportunities to travel and a career path to follow in stark contrast to the political gloom beginning to press itself even on her blissful existence. She began to attend political meetings in London where disarmament was strongly advocated. She clearly recognized the danger of Hitler’s rise to popularity in Germany on a platform of resistance to reparations.

The reduction of armaments is the only solution to the question of safety – armaments are the sure preparation of war – together with the control of the public by papers like the Express … the necessity of hope in times almost dark with despair … what possibilities to act now.65

Holland and Germany, 1933

To say the ‘modern schools’ is not to indicate those built in the last ten years, those that hang a contemporary mantel on an old program, but rather those that, according to the spirit of our architecture movement, address the essential problem of the new schools at the outset of their creation.’ Ernst May, 1928.66

The summer of 1932 saw Mary finish her thesis and to much acclaim, graduate from the AA. Press photographers on the roof of the building caught a shot of Mary hoisted on to the shoulders of ‘fifth year men’.67 The following year Mary and her friend and fellow student Judith Ledeboer (who Mary referred to as Led)68 made a trip to Germany and Holland. They motored in Judith’s two-seater Austin. The formal purpose of the trip was to study German Baroque architecture and write a report which was duly presented to Howard Robertson69 at the end of the year. But the two newly qualified architects were eager to find out as much as possible about the state of the profession in that country which was changing rapidly. This was a critical time in Germany for architects and artists many of whom were faced with the challenge to their integrity and modernist ambitions by the rise in popularity of the National Socialist German Workers Party led by Adolf Hitler.

Under the short-lived Weimar regime, architects, designers and artists, many of whom had developed their ideas for a new understanding of the arts during the war years, came to maturity through the reconstruction of the cities in the spirit of Modernism. Every German city envisaged a planned municipal redevelopment with good quality social housing served by public transport, parks, schools and community centers designed with modern equipment and attention to light, health and well-being. There was a great deal to explore that was new, forward looking and essentially modern.

2.9 Mary and Led (Judith Ledeboer) waiting at a ferry crossing, Germany 1933. IOE Archives, ME/A/8/21

Armed with a collection of contacts that had been conveyed by Robertson and Yerbury, they set off on their journey with a clearly defined task but time to find much of interest from their own point of view.70 On their way to Germany, the women paused at Mary’s favourite Dutch town of Middelburg where she and Led stayed as before at the Hotel Abdij. Here her memory of previous visits was stimulated by ‘smells of Dutch interiors … details of buildings, colours of shutters, cobblestones.’ Motoring in to northern Germany they stopped for a while at Essen and took the opportunity to call on the city’s architects in their offices ‘we simply blazed in without even a personal introduction’. The city architect Professor Roskoten gave them a two-hour tour in his own car of new housing schemes before taking lunch at his home. Roskoten offered them photographs and plans and a list of new buildings.

Mary was always interested in how architects arranged their studios and offices and at this time witnessed some interesting innovations. She also generally commented in her journal on the interiors of the architects’ homes she visited as well as the offices and studios where she witnessed the planning of their work. She considered Roskoten’s office an ideal sort of place, ‘flourishing and wooden and beautifully furnished’. Perhaps envisaging her own preferred working space for a future career in design, she particularly enjoyed the drawing office which was ‘light and airy with about eight draughtsmen and models and photos and even a basin and a clothes hanging space’.71

While in this industrial region, Mary and Led took the opportunity to visit churches and other public buildings pointed out by their hosts and as was often the case on her travels, Mary made sure to include an educational establishment in the itinerary. One building visited was a newly-constructed kindergarten. Here, Mary made extensive notes paying particular regard to the detail of interiors, to colour and to scale. She found the kindergarten to be

lovely with little flowers and birds as labels everywhere. Everything smaller – towel rails and basins, chairs and lavatories – all to the right scale. Beautiful colours are everywhere and all the children in the sunshine outside and one washing up the meal things in the dining place. The main hall of pale yellow with fawn curtains and deep plush blue curtains on the stage. Another very pale grey room with a glorious deep gold yellow curtain. Colour everywhere of beautiful schemes. Great glass stairs and lovely entrance hall.72

While in the Rhineland they stayed at a hotel where the proprietors were astonished to discover that the two young women travelling together were budding architects, studying the region. Their conversation led her to comment that, ‘apparently, as yet, there are no openings for women here’. In Cologne they called on the industrial architect – Emil Rudolf Mewes (1885–1949) – who, Mary observed, ‘had an enormous dimple on his chin’ and were shown around his offices which were, ‘intensely interesting and (with) wonderful organization … with a gymnasium and sun room and balcony in the roof. Freshness and simplicity of design resulting in something really beautiful and essentially practical and economical.’

The Bauhaus, founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius (1883–1969), was coming to the end of its possible existence in a country by now dominated by ideological and racist objections to the politics and to the products of its founders. By the summer of 1932, Gropius had already left the Bauhaus at Weimar and was to leave Germany for Britain with the help of the architect Maxwell Fry two years later. The school, now in Berlin under the direction of Mies van der Rohe, was already fractured as a force uniting the arts and crafts in a style reflecting the modern era and it was closed shortly after Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in the spring of 1933.

Mary and Led gained insights into the implications of political upheaval in Germany when they visited the School of Architecture and the Arts in Frankfurt where they met the director, Professor Fritz Wichert, ‘a really charming, very sensitive person reminding me in an odd way of (Carl) Milles with a drawn down mouth hunched shoulders and dark hair and eyes’. They toured the school before having lunch together with him at his home. The Frankfurt school was organized in the Bauhaus style, ‘where architecture, fashions, carpentry, photography, weaving, poster designing – in fact all the technical school – all connected up with the trade and the factories to abolish the idea of Art and Craftiness, and be a means of getting decent utilitarian beauty into the whole of life’.

Wichert had been director of the art museum at Mannheim from 1909 to 1923 where he developed his ideas on a comprehensive public education in the arts before taking up the directorship of the Frankfurt school. He believed strongly in the power of the ‘new’ as defined at the time by the School. Here was a strong commitment to the idea that ‘new people create new buildings but new buildings also create new people’.73

The visitors discussed over lunch Wichert’s commitment to modern art, its acquisition and display and of the vital importance of educating public opinion to the idea of good art in everyday life through lectures, exhibitions and by mass meetings. ‘The time has come he says, for a movement of that sort throughout Germany.’ Like Ernst May, who at this time was the city architect in Frankfurt, Wichert optimistically believed in the ‘New Building’ [Neues Bauen] a tendency less tied to the impulses of the avant garde than the Arts and Crafts movement and a belief in the power of the environment to influence character.74 Wichert survived the Nazi period untainted, finding exile not in America but on the island of Sylt as post-war governor before his death in 1950.75

While in Frankfurt Mary and Led might have seen some of the new housing developments with integral schools designed according to a progressive pedagogy that rejected the heavy disciplinary Prussian style of the past. Under Ernst May, these schools were emerging with many of the features that were to become commonly associated with the New School as defined by Alfred Roth in the 1950s.76 Comprised of low wings instead of monumental brick blocks, the new schools were light, often with entire glass walls that opened out onto student gardens. Specially designed moveable furniture that was light and colourful celebrated a new spirit of education. Pavilion schools were constructed at this time with particular attention to opening up the classroom to the elements, sometimes with open-air walkways.77

Further Travels

Live in fragments no longer. Only connect and the beast of the work, robbed of their isolation that is life to either, will die.78

Mary was qualified by RIBA in 1934, the first female member and in her papers for the Hertfordshire Society of Architects she was described as ‘Mr M. Crowley’.79 This was an important moment in the world of architecture as well as arts and design more generally. We have already noted the experiment in bringing together all of the art forms at Cranbrook in the USA and the Bauhaus in Germany. Outside of these utopian projects there were important experiments in social housing and many of Mary’s contemporaries newly qualified from the AA were engaging in housing work. At the other end of the social spectrum the application of modernist principles in domestic architecture by a vibrant generation of artists, architects and designers was producing work attracting international interest. For Mary, newly qualified at the age of 27, and having toured significant developments in Europe, it seemed that housing was the avenue by which to pursue a career in architecture. However, her own interests and her relationship with Laurin Zilliacus kept drawing her back to the question of how to arrive at a new form of common school for the future. Meanwhile, Mary found time in the summer months of 1934 to accompany Zilliacus as he travelled in Sweden contributing to an educational conference.

From time to time, Mary would copy into her diary extracts from novels, journals or other published sources that she wished to keep close to her for inspiration. In her diary, during this time, Mary inscribed the words from a lecture given by Zilliacus some two years earlier at Bedales where he had outlined his views about the fundamentals of human happiness and existence.

the fundamental urge of our being is the richest and most harmonious development of all our currents of life and their absorption into the main current of life in our own universe – therefore if we will only look within and see with eyes unprejudiced by catchwords, what it is that we really want, we shall find that it is not the line of least resistance, not of narrow ambition, not of denial of part of ourselves but it is to bring all parts to the perfection of which they are capable, to harmony with each other and to absorption in even wider activities.80

2.10 Mary with Elizabeth Denby in Stockholm, 1934. IOE Archives, ME/A/8/2

With such encouragement to deeply feel and follow her desires, Mary was absorbed by her time spent in Zilliacus’ company in the summer of 1934. Her good friend Elizabeth Denby joined them for some of the time.

In the place they called their own special city, the couple stayed by the water’s edge at the Hotel Reisen occupying a fifth floor ‘flat’ which Mary sketched and described, characteristically detailing the colours of what she could see in the harbour below. She described this little ‘home’ with its ‘entrance lobby, bathroom and large bedroom with two corner windows’ in affectionate terms,

everything tidied and welcoming us and outside, below us, the pattern of the quayside … with the black and white funnelled ships, blue painted trams and red houses, coils of ropes – and the shimmering water catching the sunlight by day and dotted over with moving ships and boats and ferries. And at night a fantastic fairy palace with red green blue yellow lights.

The colours of the city were enveloping, seemingly protecting them from the pressures of the world they must return to. ‘Our arrival in Stockholm was in the greyness of soft shimmer and we had left in a soft greyness the evening before.’

Mary spent most of late summer and autumn of 1934 in Sweden, Denmark and Finland, sometimes alone with Zilliacus and occasionally accompanied by his friend, the teacher, Gustav Mattsson. In November they travelled from Copenhagen to Gothenburg and on another occasion from Stockholm to Malmo by train. Mary wrote in her diary of long enjoyable suppers in restaurants and twice there were more intimate meals with Zilliacus and Gustav Mattsson at the Hotel Reisen, ‘our first supper party entertaining a friend’ where she was able to imagine being man and wife. These comments rather betray Mary’s longing for a settled family life with Zilliacus which she could imagine strongly but never actually realize.

They had visited Mattsson’s school – Olaf Scholaw – at that time occupying a temporary building of flats. This was an unusual school where the teaching was unorthodox and rooted in Gustav Mattsson’s interest in psycho-analysis.

The following summer, 1935, saw Mary and Zilliacus once more accompanied by Mattsson in Switzerland for a two week holiday, but by September Mary was back in London in full time work at the Yerbury’s Building Centre. Her parents, especially her father, were at this time becoming exasperated about her continuing liaisons with Zilliacus and pressing her to cease their relationship.

2.11 Mary on a boat reading. Mary spent much time travelling on boats between the various parts of Scandinavia she visited. There is no date on this image but appears to be 1930s. IOE Archives, ME/A/8/2

NOTES

1 MBC diary, August 1931. ME/A/4/34.

2 A. Powers (2005) Modern: The Modern Movement in Britain. London. Merrell Publishers.

3 Maison Planeix by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret (1927).

4 M. Fry (1975) Autobiographical Sketches. London. Elek. p. 14.

5 Women on the first year role were Mary B. Crowley, M Gilbert, J. P. Yenning, M. Atkins, R. E. Benjamin, A. R. Gascogne, P. Jackson, Z. T. Maw, F. M. Raymond, A. M. Robertson, and M. J. Ryder.

6 The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) did not admit women until 1898. The Glasgow School of Art (1905) and The University of Manchester (1909). See Lynne Walker (1997) p. 14.

7 Judith Ledeboer trained at the Architectural Association, London (1926–1931), and won the Henry Florence Travelling Studentship (1931). Ledeboer practiced architecture from 1934 in partnership with David Booth (1939–1941 and 1946–1962) and John Pinckheard (1956–1970). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ledeboer, Judith Geertruid (1901–1990), architect and public servant by Lynne Walker, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/66415.

8 M. Wigley (1995) White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of Modern Architecture. Cambridge, MA. The MIT Press. p. 99.

9 Mary made acoustic measurements at the theatre.

10 Daily News, 4 and 6 January 1928, cited in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Gavin Stamp, Elisabeth Scott, Architect http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/53117ODNB.

11 The Architects’ Journal, 12 July 1972, p. 68.

12 Mallows was the son of the architect C. E. Mallows (1864–1915) and went on to a career in South Africa.

13 Records of student cohorts held at the Architectural Association Archives, Bedford Square, London.

14 Mary achieved a distinction for her history notebooks.

15 ME/A/3/5: The Architect and Building News, 15 July 1932, p. 75; The Observer, 10 July 1932; she also won the medal from the Société des Architectes France for best student of the year. The Builder, 22 July 1932.

16 Architectural Association Journal, October (1932) p. 103.

17 Sir Geoffrey Alan Jellicoe, landscape designer, taught at the AA (1929–1934) and developed a romantic attachment to Mary. See below, p. 71.

18 Sir Howard Morley Robertson taught at the AA from 1920.

19 Francis Rowland Yerbury worked at the Architectural Association as a post boy from 1901, became secretary of the AA in 1911 retiring 36 years later in 1937. He had wished to become an architect but his family had not been able to afford an education extensive enough. He was a photographer and among his books were Modern European Buildings (1928), Modern Dutch Buildings (1931), and Small Modern English Houses (1929).

20 See below, p. 69.

21 Francesca Wilson Horder (1993) A Life of Service and Adventure. London. Privately published. p. 109. I am grateful to Siân Roberts for this reference. See Siân Roberts, ‘Place, Life Histories and the Politics of Relief in the Life of Francesca Wilson, Humanitarian Educator Activist.’ University of Birmingham unpublished PhD Thesis (2010).

22 See for example Elisabeth Benjamin in conversation with Lynne Walker in C20: The Magazine of the Twentieth Century Society, 2011.

23 See below pp. 46–8. Carl Milles sculpted the Poseidon statue in Gothenburg, the Gustaf Vasa statue at the Nordiska museet, the Orfeus group outside the Stockholm Concert Hall and the Folke Filbyter sculpture in Linköping.

24 MBC diary, 23 December 1928; see also The Architectural Association Journal, June 1931, p. 23.

25 Brandon-Jones letters to MBC. ME/A/8/3.

26 (Philip) Hope Edward Bagenal, architectural theorist and acoustician.

27 MBC diary, 23 December 1928.

28 MBC diary, 11 January 1929.

29 A number of these reviews in the architectural press have been reproduced in Irena Murray and Julian Osley (2009) Le Corbusier and Britain. London. Routledge.

30 Architectural Association Journal, XLVIII, no. 545, July 1932. p. 38.

31 The medal was awarded annually from 1921 to the best student of the year who had gained the AA Diploma and was the result of the recent formation of the Franco–British Union of Architects. The Architectural Association Journal, May 1922. p. 238.

32 A. Saint (1987) p. 41; see also A. Powers (2007) Britain. London. Reaktion Books. pp. 59–60.

33 Architectural Association Journal, October 1932, p. 102. In 1982, Mary worked with David Medd on the extensions and development of Melbourne Village College (1959) in Cambridgeshire, the eighth one of the series of village colleges; MBC, Report on an Educational Centre.

34 Lynne Walker (1997) p. 11.

35 F. R. Yerbury (1931) Modern Dutch Buildings. London. Ernest Benn Ltd.

36 Yerbury’s Modern Dutch Buildings was published in 1931. This included images of Duiker’s open air school in Amsterdam.

37 MBC diary, April 1930. ME/A/4/34.

38 As city architect from 1928, Dudok was responsible for many civil buildings including baths and schools and housing developments.

39 MBC diary, April 1930. ME/A/4/34.

40 Mary regularly lodged at the the Hotel Abdij.

41 For more on Dorothy Annan and her school based work, see Laara Schröder, ‘Dorothy Annan: Craftswoman with a Cause’, The Magazine of the Twentieth Century Society, Autumn, 2011. pp. 10–13.

42 MBC diary, April 1930. ME/A/4/34.

43 British Library Architects Lives. Tape 2. 7 August 1998.

44 Preface by Frank Yerbury in (1925) Hakon Ahlberg, Swedish Architecture of the Twentieth Century. London. Ernest Benn. p. vi.

45 Letter, Ostberg to Saarinen, 27 March 1930. Cranbrook archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, USA. Saarinen papers 2:6.

46 Edward Bottoms, ‘The Maleren Queen’. Architectural Association Archives paper.

47 The Stockholm Exhibition was reviewed in The Architectural Review, August 1930.

48 MBC diary, 19 July 1930.

49 MBC interviewed by Louise Brodie BL Architects Lives, 1998.

50 Howard Robertson, ‘Sensitive Simplicity. A Masonic Children’s Home by Hakon Ahlberg’, The Architect and Building News, 19 December 1930. p. 821.

51 The house was designed by Carl M. Bengtsson.

52 Andra Uplagen (2007) Carl Milles Millesgarden. Stockholm. Goran Bramming Gallery. p. 11.

53 British Library, Mary Medd interview with Louise Brodie, 1998. List Recordings C467/29/01-06.

54 Milles produced a large body of work during the 20 years he spent as artistic director of the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, north of Detroit. The Cranbrook Academy of Art was founded officially in 1932 after many years of gestation.

55 Harry N. Abrams Inc Publishers, New York, in Association with The Detroit Institute of Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1983) Design in America. The Cranbrook Vision, 1925–1950. p. 243.

56 The Cranbrook Foundation was an extension of the home of George Booth a benefactor and custodian of the arts.

57 Gottlieb Eliel Saarinen (1873–1950). Saarinen had won second prize in an architectural competition hosted by the Chicago Tribune and arrived in the USA in 1922. Half of the more than 100 entries came from northern Europe. Saarinen was a friend and admirer of the Russian author Maxim Gorki. Saarinen visited Gorki at his home in Finland in 1905 and at Capri in 1913.

58 MBC diary, 19 March 1928. ME/A/4/32.

59 See below, pp. 181–3.

60 British Library Architects Lives. Tape 2, 7 September 1998.

61 Mary later succeeded in seeing the film Metropolis, commenting in her notebook, ‘the story was useless but the photography and sets were marvellous’.

62 Geoffrey Jellicoe studied at the Architectural Association in London and later became its principal. His book Italian Gardens of the Renaissance (1925) would have been known to Mary and her family. Jellicoe was particularly fond of Mary and there is evidence in her diaries that he was at one time intent on marrying her. ME/A/4/37. Read more at: http://www.gardenvisit.com/biography/sir_geoffrey_jellicoe#ixzz19sbDhsRD. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

63 W. B. Yeats (1899) from ‘The Lover Tells of the Rose in his Heart’, quoted in Mary Crowley’s diary, April 1931. ME/A/4/34.

64 This was the 1930 first edition of the work that was later republished as Savage Messiah.

65 MBC diary, 1931. ME/A/4/34. Her emphasis.

66 Ernst May, ‘Die Neue Schule’, Das Neue Frankfurt, 11 December 1928. p. 225.

67 MBC diary, 12 July 1932. ME/A/4/35.

68 Ledeboer had trained alongside Mary at the AA (1926–1931). Led was mainly known for her housing work but also was interested in education, especially girls’ education, and designed kindergartens, adventure playgrounds, and a girls’ school. Lynne Walker. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

69 Sir Howard Morley Robertson had taught Mary Crowley and Judith Ledeboer at the AA.

70 Robertson and Yerbury had made a trip together to Germany in 1927 including Frankfurt where Yerbury photographed Modernist schools designed by Ernest May.

71 MBC diary, 22 September 1933. ME/A/4/36.

72 Ibid.

73 Fritz Wichert, ‘The New Building Art as Educator’, quoted in Susan R. Henderson, ‘”New Buildings Create New People”: The Pavilion Schools of Weimar Frankfurt as a Model of Pedagogical Reform’, Design Issues, 13, no. 1, Spring, 1997. p. 30; Ulrich Neiss (ed.) ‘Kunst fur alle! Der Nachlass Fritz Wichert’, www.stadarchiv.mannheim.de/Wichert.

74 Henderson (1997).

75 Rose-Carol Washton Long, Max Beckmann and Maria Martha Makela (2009) Of ‘Truths Impossible to Put in Words’. Max Beckmann Contextualized. Bern. Peter Lang. p. 180.

76 A. Roth (1950) The New School. Zurich. Girsberger. Second edition 1957.

77 Henderson (1997) p. 37.

78 E. M. Forster (1910) Howard’s End. London. Edward Arnold.

79 DLM (2009) p. 3.

80 MBC diary, 3 September 1934.