Sustainable Identity: New Paradigms for the Persian Gulf

This essay will address my ongoing academic research and professional applied design studies related to re-conceiving the principles and aesthetic basis of future built environments of Persian Gulf countries, so as to better achieve their potential for phenomenal and cultural sustainability. The study is partially based upon the successful research findings of the ‘Year One Pilot’ focused on the United Arab Emirates, and which was sponsored by the UAE government. These findings were published in summary in the Winter 2008 edition of 2A Architecture & Art Journal in Dubai. Furthermore, a Harvard Kennedy School Middle East Initiative Grant by Kuwait Foundation for Advancement of Science for 2009/10 allowed both an anthropological and architectural research continuation of this general topic, as published in our report on ‘New Arab Urbanism’.1 These studies have now culminated in the major new cross-disciplinary Harvard University Research Project for which I am co-editor related to all the eight countries bordering the Persian Gulf. The book, when published, will be titled the Gulf Encyclopedia for Sustainable Urbanism, and it is being sponsored by Msheireb, a subsidiary of the Qatar Foundation. This body of research complements my current professional practice in the region and over 40 years of built work in the diverse countries and bioclimatic/cultural zones that surround the Persian Gulf.

My research studies focus upon a series of key research questions that have generated the framework of our exploration, and which still remain to be fully answered:

Q1. How have decision-makers and creators of the new developments in the Persian Gulf made their key decisions? In particular, how have they incorporated concerns for the environment and culture into their programming, planning and design process, aside from the standard considerations of material function, economics and marketability? How has environmental responsibility and cultural relevance been defined and managed in the design/build process?

Q2. Regarding sustainability, is the impetus for its consideration – if it exists at all – just reacting to the chaos caused by contemporary civilizations, resulting in the climate change crisis and some of the ensuing governance requirements or media hype? Is the ‘green impulse’ popularly supported by the private and public sectors? Is it a direct expression of deeper ethical beliefs? And if so, which ones? How can future developments become effectively more sustainable?

Q3. With regard to cultural consciousness, is there a holistic dimension to be found in the creative process of the architects and planners working in the Persian Gulf? Is there a design quest to convey a ‘spirit of place’, a Genus Loci, or could the designed work be geographically located anywhere? Does context matter; if so, in what ways?

Q.4. With specific reference to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, do the new developments exhibit a particular cultural character and narrative? One view might be that identity deals directly with a particular civilization’s world view of ultimate reality; if that is so, what civilization is being represented in these new developments? If there are shortcomings in this respect, how can they be improved? What role does globalization play in these narratives?

THE CURRENT SITUATION

The topic of ‘sustainable human settlements’ and the well-being of the marine environment of the Persian Gulf is a vast challenge. It requires considerable, ongoing multidisciplinary research, as well as more in-depth and broader surveys and documentation, detailed analysis, discussions and new public policy initiatives. It also requires a dynamic archival base, which suggests the effort should be institutionalized, funded on a much larger basis and capable of being monitored on some dynamic GIS platform, which the Regional Organization for Protection of Marine Environment (ROPME), a United Nations Environment Programme-related entity in Kuwait and sponsored by the eight Gulf countries, has already started with regard to sea conditions.

It is clear that the two major sides of the Persian Gulf are experiencing completely different levels of economic investment and development. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) side on the west is verging on becoming overly developed with extensive unsustainable built environments, while the Iranian side to the east exhibits just the opposite condition, with extremely under-developed built environments but highly strategic port activities. The Iraqi coastal edge, while very limited in geographical size, nonetheless provides access via the Shatt-al-Arab (Arvand River in Iranian) to the port of Basra, while pouring into the Gulf the entire drained marsh lands and waterways of the Tigris/Euphrates valley. Oman, further removed from the Persian Gulf itself, offers a more benign picture of development, but ironically the most rapid urbanization.

However, all these sides are contributing to the unfortunate pollution of the marine environment through a number of factors: offshore and onshore oil industries that spill or seep vast amounts of oil into the waters; by substantial tanker discharges that also introduce invasive alien predatory species that endanger local fisheries and marine life; by urban dumping of raw sewage and industrial waste; by desalination and power plants; and not least by inter-tidal urban developments that destroy biodiversity and coral resources. Together, these problems cause the Persian Gulf waters to be one of the world’s most polluted seas.

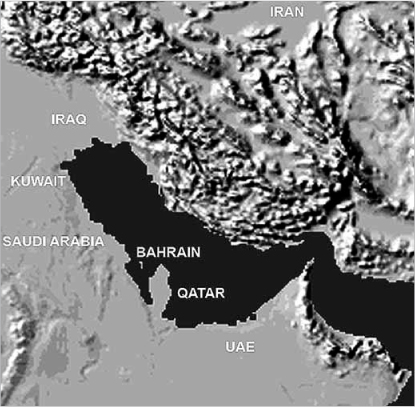

16.1 Relief map of the Persian Gulf region

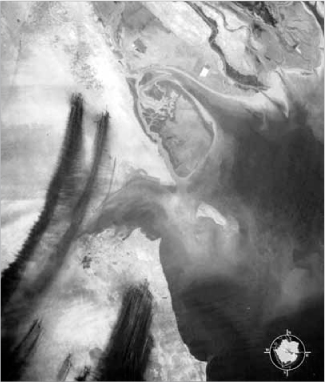

16.2 Bathymetry, ports and oil installations in the Persian Gulf

The current findings of our research and those from an evaluation based on several sustainability criteria such as the ‘One Planet Living Principles’, indicate that the majority of the current planning, design, construction and real-estate practices and models that have been used – particularly in the GCC part of the Gulf region since the 1990s – now demonstrate serious shortcomings.2 This working conclusion is principally due to the documented observations by various international agencies and professional critics of the following phenomena:

• The region’s high energy and resource consumption that showed Abu Dhabi in 2007 had the world’s highest carbon footprint per capita;

• Measures of urban and water pollution in the Gulf, as specifically recorded in the State of the Marine Environment Report 2003 by ROPME.3 This showed the four primary causes were:

1) Oil industries

– 25,000 tankers, 60 per cent of world oil transported through the Gulf;

– World’s highest oil pollution risk (1.2 million barrels a year spilled);

– Hydrocarbons in water exceed by 3 times the levels in North Sea.

2) Wars from 1980 to 2003

– Iraq/Iran War (1980–1988) = 2–4 million barrels of oil spilled;

– Iraq Invasion of Kuwait (1990–1991) = 2 million mines, 730 oil well fires, 9 million barrels spilled into Gulf;

– Iraq War (2003) = Oil well fires in Basra, etc; shipwrecks, oil spills.

3) Urban development and population growth

– From less than 34 million people in1960 to 140 million plus in 2008;

– Inter-tidal zone/biodiversity destruction by offshore construction;

– Sewage, industrial chemicals and agricultural pesticide discharges;

– Chlorine, brine & elevated temperatures at desalination/power plants;

– 66 per cent of Gulf’s coral reefs are now at risk;

– Over-fishing, use of industrial gill nets close to marine nesting areas.

4) Natural occurrences

– Shallow water, 50 m average depth, slow moving three-year cycle;

– Persian Gulf’s high water salinity and unusually high temperatures;

– Red/Green Tides (algae blooms) are disease agents for marine/human life;

– Invasive marine species due to tanker ballast emptied into Gulf.

• Uneven urban quality and cohesion, lack of human scale in cities, plus traffic congestion that is evident from even a casual drive through any of the Gulf’s urban centres now experiencing rapid growth;

• Unresolved socio-demographic dynamics due to the majority of the resident populations of the GGC being expatriates of widely diverse ethnic and economic backgrounds. As a late phase of modernism, globalization magnifies these structural problems by superimposing onto them populations from starkly different backgrounds. The resulting cultural disorientation, alienation and identity crisis remain to be resolved. What is the path forward?

• Identity Crisis: a visual/spatial loss of a vital sense of cultural identity, collective memory, traditional knowledge and values, indigenous narratives, historic textures/patterns, and sense of place. In other words, the intangible elements of heritage.

PROSPECTS FOR THE PERSIAN GULF REGION

The forms of nature are meaningful. They are the resultants of a fit-for-purpose process. Similarly, the forms of the built environment, such as cities and architecture, must ultimately be fit for their bioclimatic/cultural context or else they will not be efficient enough to be maintained, and finally will not survive. This ecological observation can apply to the existing conditions of the Persian Gulf and its surrounding built environments, where the rules of economic determinism have principally dominated development in the last decades with the noticeably retrogressive and destructive shortcomings observed above. Imagine then what the prospect might be for these communities over the next decades if more positive and constructive values – based upon a more holistic ecological fitness and the well-being of human processes – became the motivating rules and forces that governed development in the Gulf region.

Such a model was proposed by Ian McHarg, the acclaimed ‘ecological planner’, in his seminal 1969 book entitled Design with Nature.4 In it, he proposed that in order to comprehend holistically an ecological bioclimatic zone, for instance the Persian Gulf region, an inventory of all its ecosystems and life processes had be made first to understand the systemic issues involved in that region, and then to determine the most adaptive processes to achieve the solution that offered the least social/ecological cost for the maximum social/ecological benefit. Nine sectors might be considered in such an inventory, which together can provide an integrated picture for future planning and action: Ecosystems; Built Environments; Transportation; Agriculture; Socio-Cultural Patterns; Health; Water; Energy; Economy.

Without having the benefit of such an informative and detailed inventory and analysis available as yet for the Persian Gulf, but based upon our on-going Harvard University investigations to date – and those published by ROPME or reviews of the master-plans for various regional cities and major projects – the following observations and impacts can be made generically about the prospects for the Persian Gulf region:

1. The marine ecosystem will reach its ‘tipping point’ in terms of pollution in the near future due to the four primary causes discussed earlier.5 The mitigating steps proposed by ROPME include:

– Conservation and restoration of the marshlands of Lower Mesopotamia

– Integrated management guidelines for coastal areas and legislation to harmonize development activities in these coastal zones, with its member states pledging to prevent, abate and combat further pollution from land-based building activities.

– MARPOL Convention to be ratified by member states to prevent further pollution from ships.

– Legislation for the conservation of biodiversity and the establishment of protected areas to prevent increasing mortality of fish and coral.

– Attention needed to the rise in sea-level and water temperature which are increasingly threatening the marshes and mangroves that protect coastlines and support healthy ecosystems.

16.3 Fire plumes of Kuwaiti oil fires in 1991

2. Built environments will need to avoid building in the coastal intertidal zones to protect biodiversity, and they must adopt more sustainable development strategies for water desalination, power generation, sewage and waste disposal. The estimated sea-level rises of 600 mm over the next decades and storm surges will only increase the threats to coastal development and infrastructure.

3. Transportation strategies are already under way to build major port facilities and a regional rail system. Within the regional cities, there need to be more mass transit networks and greater use of alternative energy systems for vehicles planned, plus the development of protected, shaded, cooler microclimates to encourage greater pedestrian movement.

4. Agriculture will face problems from increasing heat, pests, weeds and water scarcity. So there needs to be an encouragement of alternative agricultural systems, such as hydroponics, especially in close proximity to urban settlements. More effective approaches to saving water in agriculture must be legislated for.

5. Socio-cultural patterns exhibit many unresolved socio-demographic dynamics in the Persian Gulf region, and these need to be considered. In the GCC countries, the majority of the residents are expatriates of widely diverse ethnic and economic backgrounds, with more than 70 per cent of the work force being non-nationals. However, in these lands of great prosperity, many of these expatriates live in poverty. Expatriates do not have citizenship status and associated rights, with limits to freely perpetuating their respective social and cultural values and personal dreams of self-realization, while they are also actively building the global, branded ‘Images of Unlimited Prosperity’ in these new lands.

6. Public Health and pathology have been proven to correlate closely with environment. In one of the hottest, most arid and humid environments of the world, further stress from increasing heat waves due to global warming will undoubtedly impact on human health and quality of life – this is especially true in cities, where high densities, heat sinks caused by an over-emphasis on 24/7 air-conditioning, atmospheric pollution, noise pollution and urban tensions exist. Mitigation of these impacts need to be encouraged through the creation of naturally cooler micro-climates and more healthy environments by changing current building, urban and transportation patterns.

7. Water has long been an issue of critical concern in this desert region. Iran and Iraq at least have adjacent mountain aquifers to draw upon rivers that traverse their territories, but in the GCC, except for Oman, all the other five states fall into the UN category of having an ‘Acute Scarcity’ of water. However, water consumption in the GCC zone ranks as the highest per capita in the world at 300–750 litres per day. Aside from these high consumption patterns, other critical areas of concern are: depletion of ground water aquifers; food self-sufficiency policy of GCC aggravates water scarcity because it means agriculture dominates the water supply; prime dependency on sea-water desalination plants has negative impacts on environment; greening of deserts through the planting of indigenous species is not proving sustainable. As a consequence, the GCC established the Water Cooperation Committee in 2002 to understand better its regional water demands, and to enhance water management.6

8. Energy demand will increase with population growth in the Gulf, while global warming trends will at the same time increase demands for cooling of buildings. These forces will result in significant increases in electricity use and higher peak demands. New building types which are more energy efficient and more environmentally adapted by using mixed-mode cooling systems need to replace the current unfit-for-purpose models. Once energy demand is reduced, alternative renewable sources (such as solar, wind, bio-fuel and others) need to be developed and used in grid connections to standard power generation networks.

9. Economies have to adapt to create more ecological and sustainable urban settlements, and this goal needs to be encouraged and promoted through incentive programs that will support a more stable and energy efficient pattern of life in this region. Innovative loans and financing for project construction that is based upon long-term energy and water savings can help to promote greater use of sustainable strategies: ‘If developing countries and their businesses seize the initiative on energy productivity, they will cut their energy costs, insulate themselves from future energy shocks, and secure a more sustainable development path – benefits that are all the more desirable given the current global financial turmoil.’7

SUSTAINABLE DESIGN: TWO CASE STUDIES

A brief review of the status of sustainability consciousness and mitigating ecological actions indicates that of the eight Persian Gulf countries, it might be said that the UAE, Kuwait and Qatar are most active in developing and supporting environmental issues. The UAE has related more prominently to the land-based aspects of sustainability through the Abu Dhabi ESTIDAMA and the UAE Green Building Council in Dubai, whose programs of sustainability guidelines focus greatly on energy and water consumption. The innovative MASDAR initiative in Abu Dhabi may be the most noted development yet to experiment with the idea of an actual low-carbon, solar-energy-based urban project.8

Kuwait through the EPA, KISR and the presence of ROPME, tends to focus more on the sustainability of the marine environment, and have as yet to nurture strong sustainability guidelines for the built environment. However, an important program of waste management has now been initiated. Qatar has recently set up the Qatar Green Building Council; the country’s selection to host the 2022 World Cup has prompted the design of sustainable sports facilities; and the Msheireb redevelopment project in downtown Doha is the prime example of sustainable guidelines being applied to a new urban project. The Msheireb Properties sponsorship of Harvard’s aforementioned Gulf Encyclopedia for Sustainable Urbanism research project also has the potential to generate important scientific and socio-cultural recommendations for more holistically sustainable strategies for future life in the region.

Saudi Arabia has in recent years launched its Saudi Green Building Council, with few projects that have actively incorporated either LEED or BREEAM sustainable standards. Its new Atomic Energy City under design at this time outside of Riyadh based on sustainable standards shows promise. Bahrain and Oman probably have lagged the most in this field; Iraq due to continued internal strife has had little opportunity to consider this subject, with the other countries falling somewhere in between. Iran, due to imposed international sanctions, internal issues, and its more limited public and private investment in urban development, has neither shown great attention to sustainability nor to reducing the apparent excesses in energy or water consumption patterns. Iran, a self sufficient nation in many ways, remains the ‘elephant in the room’ that hopefully once stirred and released from its encumbrances will become a leader in sustainable development, particularly as aided by UN-Habitat’s best practice standards.

Two selected case studies from my own projects will be now discussed here to illustrate the specific characteristics, issues and challenges that projects based upon sustainable principles have considered. The aim is also to discuss what lessons can be gleamed from implementing these kinds of mitigating design approaches in the Persian Gulf region.

DESERT RETREAT, UAE

Client: Aldar Properties, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Professional Team: Architects: KlingStubbins, USA

Design Consultant: Ardalan Associates, LLC, USA

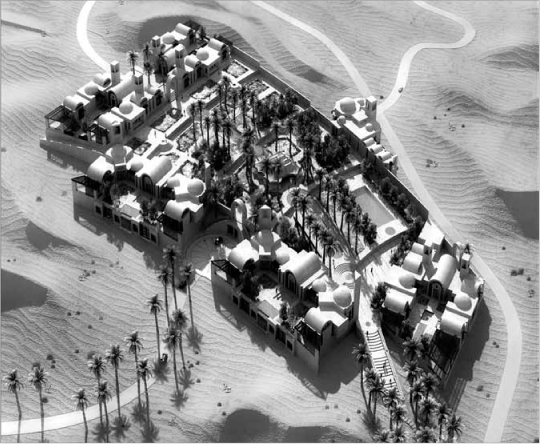

In 2007, when thinking about the Desert Retreat, an intimate, private extended family place for an Emirati national in the remote deserts of the UAE, I came to the conclusion that what can be valuable in the design theme and its architecture is to set a high standard of archetypal significance (see Plate 26). Not just to repeat the historical ‘pastiche’ version of traditional architecture, nor the aseptic ‘avant-garde’ modernity devoid of culture, but to search for what Joseph Campbell called the ‘monomythic’ and primordial common ground narratives of space, time, forms, signs and symbols from the Persian Gulf region, and from around the world, to be realized in a unified new creation of traditional values and contemporary opportunities.

In keeping with the essential nature of the site, the retreat is to be constructed of architectural concrete made from the red sand of the site, washed and blended with exposed aggregates from the adjacent Hajar Mountains to alleviate its visual heaviness. Teak and sandstone complete a material palette that complements the selection of a site in an ecologically adapted oasis landscape. The place should evoke a primordial sense of the origins of mankind, somewhat as the historic remains of the region give one the awe inspiring sensation of ancient beginnings.

16.4 Desert Retreat aerial view, proposed design for Al Ain in the UAE

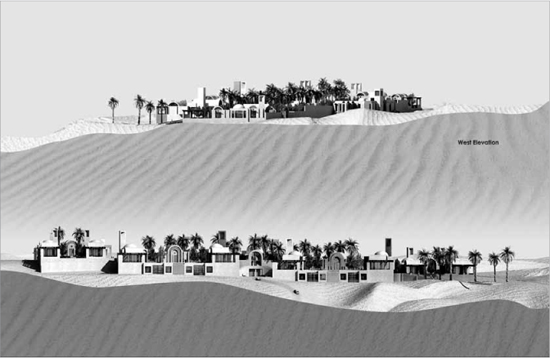

16.5 Desert Retreat elevation

THE INTELLIGENT TOWER, DOHA, QATAR

Client: Gulf Organization for Industrial Consulting (GOIC), Doha, Qatar

Professional Team:

Architects: KlingStubbins, USA

Design Consultant: Ardalan Associates, LLC, USA

Engineers: ARUP, USA/Qatar

The typology of high-rise architecture presents us with a significant design challenge today as we strive to reduce the energy consumption of buildings as a means of achieving sustainable development. High-rise typologies place great value on the occupants’ access to natural light and views. To meet this demand, the ratio of perimeter envelope to floor area is typically high. As a consequence, the solar gain per unit of floor area is also high, and the energy required for cooling becomes significant. This is particularly true in the Persian Gulf region where solar gain is extreme and the opportunity for natural ventilation is seasonally limited. While keenly aware of this phenomenon, the project for an Intelligent Tower in Doha which won an international design competition in 2007 also recognizes that architecture, like all complex systems, is the resultant vector of myriad criteria. Beauty, function, land use, financial return, all rightly demand consideration: each one battles for primacy, each seeks optimization.

My vision for this 70-storey tower grew out of our knowledge of and experience with the functional demands on first-class, commercial office towers. So our design proposes a modular, flexible workplace that can support organizational and technological change and ensure a high-quality indoor environment for every occupant, while also reducing energy consumption and operational expense. In addition, the building design and the contracting process will facilitate rapid construction. Together, these factors will establish the building as a leader in the Doha office market. Materially, the tower’s exterior is a unitized, high-performance, curtain-wall system with non-reflective, minimum-tint glass and top-quality aluminum panels. The exterior is light in colour, as is appropriate to the environment and in harmony with the Qatari traditions of predominantly white architecture. The criteria governing the selection of internal materials and finishes will include: utilization of regionally available and recycled materials; non-endangered natural materials; low-emission paints, carpets, adhesives and sealants; and the use of construction IAQ practices and a ‘green housekeeping’ program.

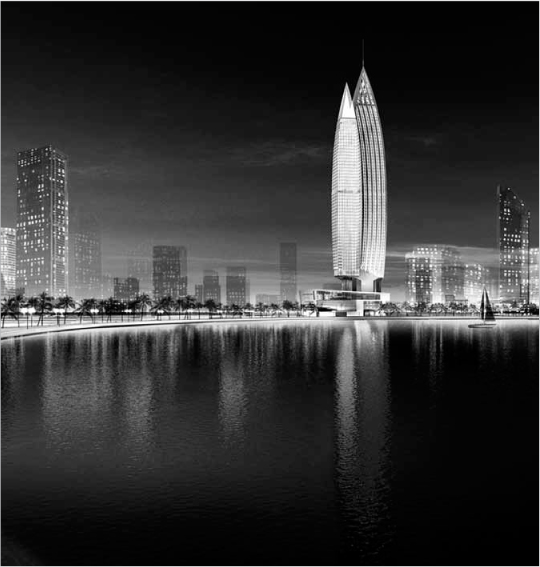

16.6 GOIC Intelligent Tower for the Doha Corniche, Qatar

The Intelligent Tower will employ a number of energy-generating strategies including wind turbines and photovoltaic panels. Likewise, energy-saving strategies will include: exterior sun-screen devices; triple-layer, high-performance glazing with integral shading device; controlled daylighting; natural ventilation; chilled beams; under-floor air and telecommunication distribution; occupancy lighting controls; efficient lighting and plumbing fixtures; gray water re-cycling; central district cooling; construction efficiency and waste minimization strategies; digital control energy management system; full building commissioning for optimized energy efficient operation. Current computer modeling software affords us the opportunity to simulate the performance of these strategies early in the design process. These simulations are parametric and thereby clearly quantify the relative impact of each strategy. Knowledge of the cost/benefit of these sustainable strategies – in terms of both capital and operating costs – from early on allows the owner to make informed choices prior to the refinement of the contract documents. This reduces the amount of time required for design changes and increases the length of time devoted to producing high-quality project documentation.

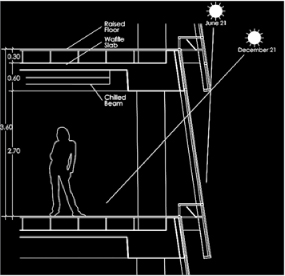

16.7 Typical office floor section for the GOIC Intelligent Tower

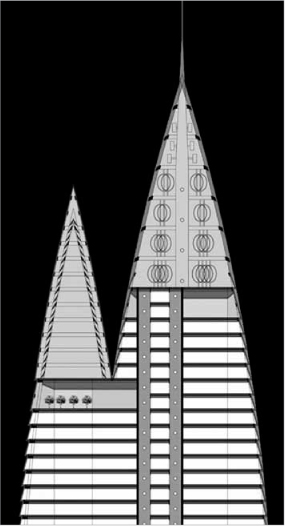

16.8 Diagram showing the wind turbines and solar panels on the GOIC Intelligent Tower

In that the mission of the client, GOIC, is to promote industrial development within the wider Gulf Cooperation Council area, it was fitting to incorporate into its headquarters those progressive technologies which can exploit certain characteristics of the climate to generate energy and potentially stimulate greater use of alternative renewable energy systems. Therefore, solar arrays and wind turbines will be located in the tower’s two finials. Given the pace of development of such technologies, they are to be located not only where they would achieve optimum output, but also where they could be replaced when more effective models become available. In summary, the Intelligent Tower aims to be at once a beautiful structure resonating with the traditions and aspirations of Persian Gulf states, an effective office building fostering a creative and productive workplace, and an efficient machine minimizing energy consumption and sponsoring innovative sustainable technologies.

These two projects, to name just a few, have not been implemented; they exist as theoretical constructs which are yet to be lived in and tested. But these initiatives are also cutting edge-design proposals to address and directly mitigate both the more tangible energy efficiency and sustainability issues and the equally important, but even less tangible, cultural aspects.

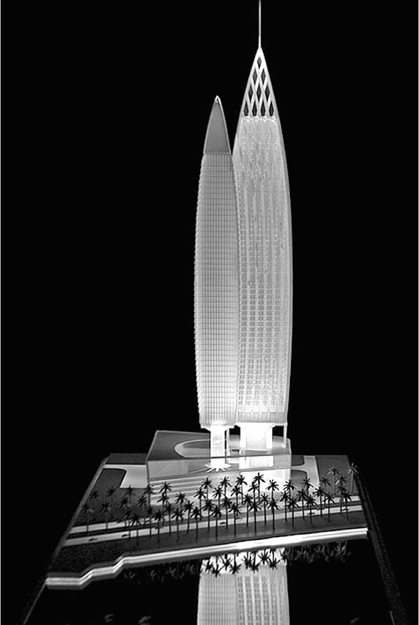

16.9 Lucite concept model of the GOIC Intelligent Tower

VALUES AND DESIGN OPPORTUNITIES

In response to the cultural identity issue raised at the beginning of this essay, it may be instructive to review the basic attitude of Islam to nature. It echoes the same Biblical sources as the Judaic-Christian view, but with a significant difference. Ian McHarg in Design with Nature made some very salient observations on this issue.9 In his view, while Islam emphasized that mankind could metaphorically make paradise on earth and make the desert bloom, the responsibility and relationship to nature was that of stewardship; mankind was both the custodian of nature and the servant of the divine. Moreover, for the settled peoples, the ‘garden paradise’ metaphor became an ingredient of urban form, while for the nomad the reverence for the earth was so great that mankind was enjoined to leave no trace of having even touched the land. However, McHarg then continued with a somewhat controversial hypothesis:

Historically, the Judaic-Christian attitude has been based upon Genesis and, quite contrary to Islam, emphasized the conquest of nature. Man was separate from the temptations of carnal nature and must have dominion over the bestial earth; he must subdue the earth … With only partial lapses by the European Romanticists of the 18th C., the history of Europeans’ attitude to nature has been one of exploitation and conquest.

If McHarg’s theory is valid, it may help explain the history of the last fifty years in the Persian Gulf region and the question of which attitude towards civilization is at work today in the operations of this region, given the observed destructive impacts upon the environment. Due to the intensity of new development in the GCC zone, and looking at the urban forms and architecture being built there today, the predominant models that have been followed seem to be those of Los Angeles and Las Vegas with regard to contemporary urban patterns and zany avant-garde architecture, while often resembling Disneyland wherever pastiche gestures toward the traditions of regional architecture are concerned. So this leads to the key question: are there no more valid design alternatives left?

Of course, Iran and Iraq in this region lag behind in urban development for their own reasons, but the civilizational question as it relates to architectural style remains the same. Can the new generations of Islamic cultures of the Persian Gulf today become the ‘visionary stewards of this environment’, and rise to the challenges of contemporary opportunities and globalization while remaining true to the values and aesthetic principles of their ancient heritage? The unique identity of each of these places along the Persian Gulf waters, of these millions of new pioneering inhabitants at this time, building these vast testaments of the human spirit in the 21st century, deserves far more meaningful signs of their diversely rich civilizations than what is being realized today. Can then the next phase of development achieve a more authentic, environmentally sustainable and civilizational narrative relevant for the identity images of this region?

Art, architecture, cities, and their relation to the natural environment of the Persian Gulf, offer the major opportunity to the creative decision-maker, be it state institutions, companies or the individual – not only as a vehicle of economic gain, nor only as aesthetic satisfaction, but also a powerful semantic conduit between the microcosm of earthly existence and the macrocosm of timeless existence. In other words, between the myths and profound beliefs of ancient civilizations and our own contemporary times; between the collective unconscious of humanity and the individual psyche.

FURTHER DESIGN EXPLORATIONS

Now, moving onto the issue of the future aesthetics of architectural and urban expression for the Persian Gulf region, it has been said that the functional domain of holistic aesthetics is based upon the simultaneous and profound awareness of the hidden and the manifest aspects of external reality.10 The artistic search for the deepest mysteries of this awareness is centred upon a personal and direct state of confrontation with reality in its broadest aspects, requiring no intermediaries, and which may lead to an epiphany. In the contemporary secular world in which most architects work, how to express this transcendent, spiritual experience, but not only through the canons of organized religion becomes their prime search. What can we learn from other pivotal historic periods of creative expression to guide our next steps? Research in philosophy, design and the arts can contribute to cross-fertilization of promising ideas. In 1910 Wassily Kandinsky wrote:

The great epoch of the spiritual which is already beginning, or, in embryonic form, began already yesterday … provides and will provide the soil in which a kind of monumental work of art must come to fruition.11

In the world of the artist, the move is away from representational art towards abstraction, preferring instead symbolic colour and form as the means of expression in an attempt to reach a higher and deeper dimension of meaning, the most pervasive of which is that of the spiritual. It is a reaction against the limitations of the pervading rationalist and materialist world views of contemporary society. The role of the artist/architect is thus to free and reinvigorate modern design with greater meaning. Maurice Tuchman’s essay in The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985 observes that: ‘The five underlying impulses within the spiritual-abstract nexus – cosmic imagery, vibrations, synesthesia, duality and sacred geometry – are in fact five structures that refer to the underlying modes of thought.’12 To these aspects should perhaps be added three more key impulses.

The first is a silent sense of the unity of existence – at oneness with the infinity of the universe – which was a pervading theme of the earlier 19th-century Transcendental Movement, characteristic of the writings of Ralph Emerson and Walt Whitman in America, and which continues to influence many creative individuals today. This theme is also the core of the Wahdad-i-wujud (unity of existence) thinking attributed to the 12th-century Andalusian mystic, Ibn Arabi, which had considerable and direct influence on later metaphysical contemplatives (including Emerson) and can be a vital source of inspiration for those who would taste of its elixir.13 James Lovelock, author of the Gaia Theory, advances the concept of looking at all existence on the Earth as one living organism, thus helping to possibly bridge the beliefs of science and faith.14

The second impulse that I would add is the appreciation of alchemy by the artist/architect as a method of dealing with matter. Alchemy becomes a metaphor not only for the transmutation of external matter from its ‘dark heaviness to light’, but most importantly for the creative person themselves. The alchemical experience holds for the artist/architect the potential for a complete psychological catharsis that can both illuminate and purify their spirit.

Light releases the energy trapped in matter.15

The third impulse is the idea of archetypes, as conceived by Plato and later explored in depth psychology by Carl Jung in what he termed the ‘collective unconscious’.16 Closely related to archetypal thinking is the field of mythology and its pivotal role in human consciousness, as particularly elucidated in the writings of Joseph Campbell and architecturally manifested in the works and thoughts of Louis Kahn.17

Architecture is the embodiment of myth.18

Through contemplative practice, the resulting comprehension of the above impulses is often characterized by a sense of the universe as a single, living substance of which humans are an inseparable part. Furthermore, inherent in this sense is mankind’s role of stewardship of Mother Earth, Gaia. Even if by this effort one is only able to catch but a brief and passing glimpse of an aspect of the systemic unity of existence, the creative attempt is still inspiring and fulfilling. The creative challenge then is how to express most saliently the perfume of this sense.

This approach provides a peculiar kind of ‘field’ of consciousness or world view as the context for the creative imagination to take place. The activation of the creative imagination may be of an audible nature that transcends mere conventional tonal or linguistic frameworks through music, song, poetry or verse. In a similar manner, it may be of a visual nature in the form of light, colour and matter expressed through art, architecture or movement. In both cases, the imagination is set into vibrations through abstract, transcendent symbols of this ‘perfume’ that have a propensity to pulsate the heart and thereby to touch the soul.19 The soul serves here as the modus operandi within humans to spontaneously sense the ineffable and the sublime – to go beyond the mere phenomenal to higher levels of realization about the realities of existence. Art and architecture thus have a transcendental potential.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

Such then is the nature and framework of this quest for holistic, sustainable identity. It is a quest to shift architecture from a kind of machine-inspired functionalist aesthetic to a more ecological and spiritually inspired design approach. The resolutions of these values and aesthetic questions remain elusive, but provide profound inspirations for more meaningful answers that touch the individual soul and collective humanity. As Frank Lloyd Wright wrote:

When you become the pencil in the hand of the infinite,

When you are truly creative … design begins and never has an end.20

To truly understand the key issues of sustainability and cultural identity, we need to begin with a cosmic, systemic awareness of the context of human existence on both a tangible, phenomenal level and the less tangible, cultural level. We need to become aware of the particular world views of the indigenous civilization, the genius loci of the place, and the optimum ecological fit of proposed developments. The mandate of good design is to elegantly realize this holistic vision in physical reality. Such an approach may provide an important methodology by which common ground can be found between the profound world views of traditional civilizations and the highest aspirations of contemporary innovations in art and architecture. Without such a common ground, the new architectural creations lack a sense of place, are environmentally unsustainable and appear as alien usurpers of an existing civilization, thus causing the identity crisis that is observable in the Middle East as a whole, and particularly in the new developments of the Persian Gulf region. Instead, we urgently need to find new ways of designing in harmony with nature.

NOTES

1 Steven Caton & Nader Ardalan, ‘New Arab Urbanism: The Challenge to Sustainability and Culture in the Gulf’, Final Report for the Kuwait Program Research Fund, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 2 December 2012, viewable at http://belfercenter.hks.harvard.edu/files/uploads/05_%20New_Arab_urbanism.pdf.

2 ‘Persian Gulf Research Project on Sustainable Design’, 2A Architecture & Art Magazine (Dubai), no. 7 (2008).

3 ROPME, State of the Marine Environment Report 2003 (Kuwait: Regional Organization for Protection of Marine Environment, 2004).

4 Ian McHarg, Design with Nature (New York: Doubleday, 1971). The book was originally published in 1969 by The Natural History Press.

5 State of the Marine Environment Report 2003.

6 Mohammed A. Raouf, Water Issues in the Gulf: Time for Action (Washington, DC: The Middle East Institute Policy Brief, 2009).

7 Diana Farrell & Jaana Remes, ‘Promoting Energy Efficiency in the Developing Countries’, The McKinsey Quarterly (February 2009).

8 ESTIDAMA: Sustainable Buildings & Communities Program for the Emirate of Abu Dhabi (Abu Dhabi: The Urban Planning Council of Abu Dhabi, 2008).

9 McHarg, Design with Nature.

10 Nader Ardalan & Laleh Bakhtiar, The Sense of Unity: The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture (Chicago, IL/London: Chicago University Press, 1973: Persian translation by Hamid Shahrokh of Tehran Municipality, 1998; Spanish edition as El Sentido De La Unidad: La Tradicion Sufi en la Arquitectura Persa, Madrid: Ediciones Siruela, 2007).

11 Quoted in Kenneth Lindsay & Peter Vergo, Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994).

12 Maurice Tuchman, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985 (Los Angeles, CA/New York/London: Los Angeles County/Abbeville Press, 1986).

13 Toshihiko Izutsu, Sufism & Taoism: A Comparative Study of Philosophical Concepts (Berkeley, CA/London: University of California Press, 1983).

14 James Lovelock, The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth (New York: Bantam Press, 1990).

15 Quoted in Donald W. Hoppen, The Seven Ages of Frank Lloyd Wright (New York: Dover Press, 1998).

16 Jolande Jacobi, Complex Archetype Symbols in the Psychology of C.G. Jung (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974).

17 Joseph Campbell, The Hero’s Journey (New York: Harper & Row, 1990).

18 The Interaction of Tradition and Technology: Report of the Proceedings of the First International Congress of Architects (Isfahan/Tehran: Ministry of Housing & Urban Development/Government of Iran, 1970).

19 Lindsay & Vergo, Kandinsky.

20 Quoted in Hoppen, The Seven Ages of Frank Lloyd Wright.

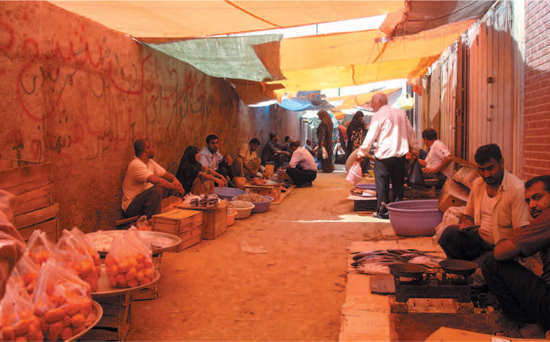

25 Local street bazaar in Bandar Abbas, Iran

26 Desert Retreat aerial view, proposed design for Al Ain in the UAE

27 Masdar City eco-town in Abu Dhabi, UAE, by Foster + Partners

28 Master-plan for the Msheireb project in Doha, Qatar, showing its fine urban grain

29 Organic urban form mixing new and old in the Msheireb project

30 Msheireb project in Doha as seen from the south-east

31 Close-up of ‘mashrabiya’ screen on the Al Bahar Towers, Abu Dhabi

32 View of chauffeur’s house in the Villa Anbar in Dammam, Saudi Arabia (1992–1993)