3.6

The Automated Gardens of LunéVille

From the self-moving landscape to the circuit walk1

And it might have been yet improved by a thought taken from one of the most flagrant perversions of taste that ever was exhibited to publick view. Stanislaus titular King of Poland, and little better than imaginary duke of Lorrain, contrived, at his fine palace of Luneville, in one of the richest and most delightful countries in Europe, full of real pastoral objects and rustic images, to degrade them by sticking up clock-work mills, wooden cows, and canvas milk-maids, all over his grounds; to the no small admiration of the Lorrainers, an honest race, better fitted for the enjoyments of a mild and equitable government, than for the relish of works of taste.2

The eighteenth-century architect James Stuart is discussing improvements to Cavendish Square in London when he calls up the contemporary example of Stanislas, ‘imaginary duke of Lorrain’, and the mechanical and artificial embellishments of his garden at Lunéville. While clearly demonstrating his disdain for Stanislas’ works, he nevertheless goes on to present Lunéville as a model for a more appropriate treatment of rus in urbe, with ‘painted sheep’, a ‘pasteboard mill’ and ‘tin cascade’ recommended for the London square, in place of real animals and structures. In the middle of the eighteenth century, Stanislas Leszczynski, father-in-law of Louis XV and twice-exiled king of Poland, enjoyed a curious reputation lodged somewhere between fact and fiction. He appears in Voltaire’s Candide, as one of the ‘forsaken’ kings spending carnival in Venice.3 At the same time, he was busy establishing himself as the king who does good, the roi bienfaisant, in his titular estate of the Duchy of Lorraine and Bar. Stanislas was a prolific writer who corresponded with key Enlightenment figures, such as Voltaire and Rousseau, and whose own work traversed utopian fable, political tract and instruction on agricultural economy.4 He was also renowned for his capricious material creations. These ranged from the invention of the baba-rhum, a rum-soaked pudding, to fauxmarbre paintings on glass, illuminations and tricks of light for garden entertainments, as well as mechanical contraptions that included self-propelling boats and a three-wheeled carriage. The garden structures built for Stanislas at Lunéville, none of which has survived, displayed the irreverent and playful use of materials and the borrowing of techniques associated with the theatre and pleasure grounds. So it is no surprise that Lunéville could be compared, at the time, to a ‘painted and corrupt Vauxhall’ and received with both admiration and contempt by contemporary visitors.5 Stanislas’ endeavours in the representational field have mostly been regarded by historians as symptomatic of the games and amusements of a dissolute court.6 Yet he attended to the connections between kingship, Utopia and society with particular sincerity and intensity in his gardens at Lunéville. His efforts to exploit the new Enlightenment conditions to create an exemplary kingdom promoted an as-if domain that was part theatre and part experiment.

Lunéville

In 1737, Stanislas had initiated a building programme in the gardens of Lunéville with the construction of the Kiosk, a small pavilion for theatrical entertainments, inspired by his time in Bender, in the Ottoman Empire. From 1741, his programme became more ambitious. He created the Bas Bosquets, or the lower garden, by draining the marshland surrounding the chateau and diverting the river Vesouze. This vastly improved the conditions of the estate and, according to Montesquieu, rendered the air healthy.7 The new land between the river and the canal was then arranged into a series of plots, with cottages called the Chartreuses, a name derived from the dwellings of the Carthusians, an order of monks known as ‘gardeners’ for following their own programmes of cultivation.8 A year later, in 1742, Stanislas built the artificial village of the Rocher, on the opposite bank of the canal. The Rocher was an extra ordinary assemblage of eighty-six life-sized wooden automata powered by water, set in a landscape of grottoes. The two ideal villages or miniature kingdoms, the Chartreuses and the Rocher, established an experimental territory in the Lunéville gardens (Figures 3.6.1 and 3.6.2). This was the setting for elaborate theatrical events, scientific demonstrations, game playing and promenades, but also intellectual discourse and an exploration of social status and courtly life.

Chartreuses

Each cottage–pavilion of the Chartreuses village consisted of a room for dining and cooking, three further rooms, service pavilions and a small formal garden for growing vegetables, surrounded by trellis walls. The tenants for the cottages were chosen by the king from among his favourite guests and courtiers and would reside there during La Belle Saison, tending their gardens.9 The king would give each of the villagers the honour of hosting him once a month, when he would expect to sample dishes prepared from produce grown and harvested by the courtier–gardeners. He would keep his courtiers in suspense by not giving any potential host more than 3 hours warning before arriving. The whole situation was, of course, staged, with real gardeners, servants and cooks doing all of the work. Stanislas was inspired by Fénelon, author of the Telemaque (1699) and royal tutor, to write his own instructive utopian text, the Entretien, and also to imitate Fénelon’s entertaining theatrical procedures for the instruction of royal princes. In one of his letters to his grandson Louis, the dauphin of France, Stanislas gives an account of the staged rural scenes, infused with affective and political content that Fénelon had fabricated for the Duke of Burgundy’s education.10 The Chartreuses village has the character of this kind of experimental demonstration in a fictional landscape. In scenes strangely reminiscent of Fénelon’s Télémaque, where artisans are transplanted from the city in order to create an agricultural paradise, the courtiers here are transferred from the château and, as forced residents of an ornamental, pocket Utopia, made hostage to a princely game.

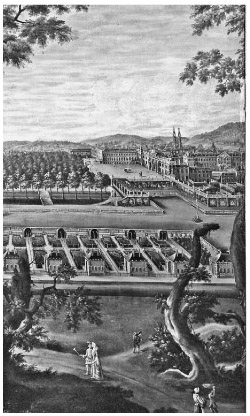

Figure 3.6.1 (left) Painting of Lunéville by an unknown artist. One of the Einville gallery panels formerly at the Musée du Château, Lunéville, but destroyed in the fire at the château on 2 January 2003

Source: © Inventaire Général – ADAGP, Musée du Château de Lunéville. Photograph D. Bastien 1990

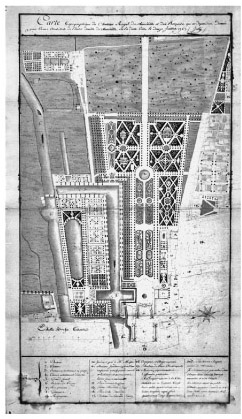

Figure 3.6.2 (right) ‘Carte topographique du Château Royal de Lunéville et des Bosquets.’ Map of the Lunéville estate by André Joly, July 1767

Source: © Inventaire Général – ADAGP, Musée du Château de Lunéville

The role-playing evident in the Chartreuses, with its comic protocol, was endemic to the life of the court at Lunéville and calls up the continuity between ludic theatre, the possible reality of a Utopia and psychological experiment. The situations of the Chartreuses overturned the prevailing social order, presenting the king as a guest hosted by his own courtiers, the courtiers in turn taking the place of gardeners and servants in creating a meal for the king. The possible scenarios of the Chartreuses, whereby Stanislas’ mistress could play the role of a dairy maid, or his secretary could be found tending a garden, bear an uncanny resemblance to Locke’s account of the prince waking up in the body of a cobbler.11 Such reversals and role-playing dominated eighteenth-century deliberation on the place of the individual in society, as is shown in concern for the status of the actor in the writings of Diderot and Rousseau.12 Eighteenth-century theatre provided, not only a target for ridicule and satire, but also the vehicle of speculation regarding shifting social orders. The inversions and oscillations of status deliberately inscribed in the topography at Lunéville cannily blurred the distinction between beneficiary and benefactor, performer and spectator, servant and king. As an interlude between political realities and imaginative fictions, the Chartreuses not only serve as a commentary on Versailles, the prevailing model of court life, but also anticipate the later transformation of this model in the Hameau of Marie-Antoinette.13

Rocher

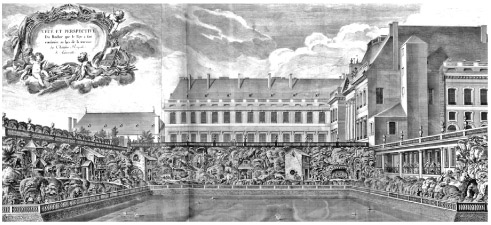

On the opposite side of the canal, the Rocher theatre–grotto of automata presented an alternative model of village life: a kingdom of even more exceptionally well-behaved and loyal subjects. This enormous display of automata in an artificial landscape was created for Stanislas by his architect, Emmanuel Héré, and his clockmaker, François Richard (Figures 3.6.3 and 3.6.4). It was an extraordinary example of the Enlightenment attempt to bring nature, society and technology to a single horizon of understanding. The theatre of the eighteenth century provided a context for the progressive blurring of the paradigm, the model, the hypothesis and the scientific or educational demonstration,14 and automata were the celebrated actors of the linked stages of salon, court and marketplace, dominating the cabinets de physique as well as the salles d’expositions.15 In the 1740s, Vaucanson’s flute-player, drummer and defecating duck toured Europe to great acclaim. Such seemingly self-moving things emerged as the central emblem of the mechanistic worldview dominant in the period, but also presaged impending industrialisation and the concomitant transformations of society. With their ambiguous, trans-categorical nature, eighteenth-century automata were tools used to test confusing relationships and were part of an era that probed the very nature of being human.16 The automaton could be didactic – an illustration of human function, or of the dichotomy of mind and matter. It evoked the monotony of repeated acts and witless conformism and provided an enduring metaphor for human foolishness, but, equally, it incited humour, wonder and curiosity. The automaton was deemed capable of supplanting the human model through a haunting resemblance and revealed a deeply flawed humanity. At the same time, human invention and ingenuity were revered for producing mechanical marvels through technical artifice.17 The Lunéville gardens harboured the conflicting meanings of automata in this period: marvellous machines afforded independent motion, as opposed to individuals incapable of independent action or thought.

The Rocher was composed of 86 lifelike automata of humans, birds and animals. These were arranged in a series of rural vignettes, of working village houses with waterwheels and windmills, in a carefully constructed rocky landscape of sandstone, minerals and stalactites collected from Mount Vosges and vegetation gathered from the surrounding countryside. The full-size androids were made of wood, wax and cloth, with heads that were modelled on inhabitants of Lunéville. It is as if Descartes’s illustration of the intellectual nature of judgement, whereby humans might be discovered masquerading as machines, is here brought uncannily to life.18 The captions to Héré’s engraving of the Rocher in the Recueil provided simple descriptions, giving scant detail of the movements or gestures of the various figures, and read almost as stage directions.19 Among automated scenes of village life were a shepherd playing his bagpipes, a peasant carving a piece of wood, a boy pushing a swing, a cat preparing to pounce on a rat that bared its teeth, men working at a forge and, above them, a solitary violin player. There were figures smoking pipes, drinking and singing in a tavern, women making butter and washing linen, a monkey being taunted by a small boy with an apple on a pole and a hermit praying in his cavernous cell.

Figure 3.6.3 ‘Vue et perspective du Rocher.’ Engraving of the Rocher from Emmanuel Héré’s Recueil T1, pl. 22.

Source: © Bibliotheque municipale de Nancy

Figure 3.6.4 ‘Le château et le Rocher de Lunéville.’ ‘André Jolyou atelier’, oil on canvas, eighteenth century. Inv. 95.731

Source: © Musée Lorrain, Nancy. Photograph C. Philippot

The Rocher was unique, not merely in imitating the mundane activities of Lotharingian village life at full scale, but in simulating the accompanying sounds, smells and textures in a tour de force of artificial effects. The importance of such detail in juxtaposition with physiognomy, physiology, pattern and collection recalls the conventions of travel writing, nascent disciplines of anthropology, botany, humanities and natural sciences, as well as the curiosity cabinet or Wunderkammer. The Rocher’s artificial landscape not only harboured a microcosm of Lorraine, Stanislas’ exemplary kingdom, but presented a microcosm of nature itself. Whenever desired, the Rocher’s agitated scenes of village life could be set in motion by the simple turning of a stopcock. The cries of animals, human voices and automated instrumentals mingled with the thunder of cannon and the lightning of pyrotechnics during spectacles on the canal. The attendant noise helped mask the shuddering and crunching of wooden cogs and wheels. The artificially disjunctive motions and fragmented gesticulations found their counterpart in the movement of tools, farm implements, the cycle of water and the turning of wheels. The Rocher landscape acted as a working diagram of the whole enterprise of irrigating, planting and preparing the land, not only of the gardens in the Bas Bosquets of Lunéville, but of King Stanislas’ greater undertaking in his contrived agricultural landscape of Lorraine. The material transmutations and illusionism of the Rocher and its corresponding ambiguities are thus set against the controlled transformations and industrialisation of a real landscape and society. The Rocher elicits disruptions, distortion of values and a neutralisation of time and scale: it is simultaneously a miniature working village and a giant clock. The dominant characteristic of both the Rocher and the Chartreuses is their presentation of several modalities of the ‘theatre of the world’, theatrum mundi, wherein life’s activities are explored through theatre. Above all, the hydraulically operated village of the Rocher, just like the Chartreuses, indicates the desire to animate, not simply to demonstrate or to know.

In the eighteenth century, animation occupied a spectrum that ranged from inherited Aristotelian notions of the soul, anima, in movement and the essence of nature, through mechanics, ‘the clockwork universe’, to theatrical role-playing and the Enlightenment justi -fication of the passions. The self-moving landscape, through recourse to the possibilities of as-if architecture, presents itself alternately as a fantastic playground, serail, model village, farm, monastery and Utopia, where the meanings of culture are at the disposal of a roi bienfaisant as the choreographer of a dramatic and fictional narrative. The creation of fictions, a concern with the synthesis of Enlightenment knowledge and, subsequently, the bringing to life of the whole enterprise, so that everything could be experienced simultaneously, were presented within a synaesthetic version of the world as theatre.

Circuit walk

By the end of Stanislas’ reign in Lorraine in the 1760s, visitors to the Lunéville gardens could take part in a ‘circuit walk’ leading round the periphery of the estate, enabling an encounter with the various pavilions and a variety of distractions that might provoke disgust, horror, amusement or delight. Inspection of the Rocher frequently marked both the beginning and the end of an instructive and entertaining journey that took in ‘clock-work mills, wooden cows, and canvas milk-maids’. The visitor could view the curiously unfolding tableaux from village life by following the ambulatory around one cross-arm of the canal, with the cottages of the Chartreuses and attendant activities arranged on the opposite bank. With Héré’s captions in the Recueil acting as a guide to the sequence of the automatic theatrical display, the Rocher readily succumbs to the spectacle of a museum installation, with the paced viewing and spatial perusal of the visitors acting as a counterpoint to the automatic landscape.

The circuit walk, as a way of observing, came to dominate the subsequent history of eighteenth-century gardens, and museum culture generally. Under Enlightenment criteria, the landscape, increasingly generalised as nature, is deemed capable of fusing divergent cultural strands and accommodating them in a single field of representation, traversed by a knowing spectator. In turn, this allows landscape and garden to be coerced and stage-managed, with the inclusion of architectural interventions as increasingly introverted and isolated vehicles for didactic messages. The landscape becomes progressively more dependent on the courtiers as readers for its actualisation, coinciding with the rise of the novel and idea of the sentimental imagination allowed to wander freely in a conceptual landscape in pursuit of self-understanding. Stanislas’ interventions in the château gardens anticipate the English landscape garden as a group of buildings within a contested topography and also the picturesque tradition as a series of views that acted on the senses, primarily aimed at aesthetic enjoyment and eliciting responses limited to questions of taste.

For Stanislas, the appropriation of the surrounding countryside had only been possible as a theatre-like and game-like annexation, given that the actual ‘workable’ territory of Lorraine was disputed, through lack of funds and Stanislas’ own status as ‘tenant’ to Louis XV. Lunéville provided him with a testing ground to explore the mechanical improvements of landscape and society. Its experimental character suggests that Stanislas adopted a strategy whereby the hypothetical aspects of Enlightenment culture could enter into dialogue with the dramatic or mimetic aspects of the traditional culture, as a common domain of as if. The full cultural hierarchy was brought into play within a representational horizon set at kingship. Indeed, the common motif across all of his representational concerns – writing, architecture, mechanics, gardens and theatre – was the vexed status of his kingship, with the Duchy of Lorraine as an as-if kingdom and landscape whose beneficence, justice and productivity were the object of the compromised king’s explorations into the possibilities of ‘good government’.

The Chartreuses and Rocher at Lunéville, with their as-if architecture, not only exemplify the ambivalent, unsteady and agitated representations that emerged in this period, but also draw attention to a cultural difficulty that remains a prescient topic for architecture today. That is, the puzzling nature of the continuity between the formation of concepts and the experiential ground, and the corresponding failure to resolve the ambiguity of a potentially non-aesthetic vision of the world. In many ways, the Lunéville gardens anticipate both the demise of the self-moving landscape, with all its inherent complexities, and the advent of autonomous machines, synthetic realism and disembodied information. The transformations of the gardens through their as-if architecture identify the moment when the notion of landscape becomes primarily a phenomenon of the mind. Thereafter, the landscape provides a background, like the paper on which a text is printed or a drawing is sketched, for the play of reason, whose wit and disguises, memories, hopes and fears remain the garden’s most active and moving elements.

Notes

1 This chapter, originally presented as a paper at the Architecture on the Move School Forum series, has drawn on the author’s previously published material:

- Tyszczuk 2007

- Renata Tyszczuk, ‘L’utopie architecturale du roi bienfaisant’, in Hatzenberger 2010, pp. 77–106.

- Renata Tyszczuk, ‘Nature intended: The garden of a roi bienfaisant’, in Calder 2006, pp. 161–87.

- Renata Tyszczuk, ‘Vérité fabuleuse: the Rocher at Lunéville 1743–1745’, in Rose and Dorrian 2003, pp. 200–11.

2 Stuart 1978, pp. 10–12.

3 Voltaire 1980 (original 1757), pp. 240–1.

4 These writings were published collectively towards the end of his life, in 1763, as Oeuvres du philosophe bienfaisant. Stanislas was one of the patrons of the first volumes of the Encyclopédie, but later withdrew his support. Stanislas also published his own compendium of inventions, the Nouvelles decouvertes pour l’avantage et l’utilité du public, Haener, Nancy (n.d.).

5 Wiebenson 1978, pp. 11–12; on Vauxhall pleasure gardens, see Altick 1978, pp. 94–6.

6 For contemporary reports on Stanislas’ court in Lorraine, see Luynes 1860–5. More recent works include Boyé 1891, Maugras 1904 and 1906, and Cabourdin 1980.

7 Montesquieu, ‘Souvenirs de la cour de Stanislas Leckzinski’, in Oeuvres completes II, p. 1236. Montesquieu visited Stanislas’ various residences in 1748.

8 In the eighteenth century, this was a popular designation of a pavilion associated with a garden; see Conan 1997, p. 60. Stanislas visited the chartreuse at Sceaux in May 1743; see Luynes 1860–5, vol. V, p. 5.

9 The houses appeared to have been built of brick or masonry, with slate roofs; however, they needed frequent, sometimes considerable, repairs and were periodically dismantled and rebuilt, as the king altered the topography and shuffled the size of the plots afforded to each tenant; see Rau 1969, p. 153.

10 Stanislas Leszczynski, ‘Réponse de Stanislas au Dauphin contenant un plan d’éducation pour les jeunes princes’, Choisies, pp. 213–40.

11 On Locke’s ‘disembodied self’ and his thought experiments, see Taylor 1992, p. 172; also Ricoeur 1992, p. 126.

12 See Sennett 1986, pp. 110–22.

13 Richard Mique, the architect responsible for Marie-Antoinette’s Hameau at Versailles, was originally in Stanislas’ employment and worked under Héré at Lunéville.

14 See, for example, Stafford 1994.

15 On play-acting automatons in this period, see Altick 1978, pp. 57–8.

16 The term automate was introduced into the French language by Rabelais’s carnivalesque epics. See Bakhtin 1984.

17 For a recent history of automata, see Kang 2011.

18 ‘Yet do I see any more than hats and coats which could conceal automatons?’ Descartes, ‘Meditations on first philosophy’ (1641), in Descartes 1984, p. 21.

19 ‘Description Du Rocher Quele Roy a Fait Construire Au Bas De La Terasse Du Chateau De Luneville Ou l’on Voit 86 Figures De Grandeur Naturelle Et dont Les Mouvements Sont Si Bien Imitez, Qu’ils Ne Paroisent Point Etre L’effet De L’art.’ Title of the engraving of the Rocher, Lunéville, from Emmanuel Héré, Recueil des plans, elevations, et coupes tant géometrales qu’en perspective des châteaux, jardins, et dépendances que le Roy de Pologne occupe en Lorraine . . . Le tout dirigé et dedié a Sa Majesté par M. Héré etc. (Engraved by J.C. François), Paris, 1750–3.