2.7

The Geometry of Moving Bodies

The idea that towns and cities should be rebuilt along scientific lines, although widely held by British architects and planners during the mid twentieth century,1 was by no means universally supported. The following account explores the nature of a disagreement between Sheffield City Council’s technical officers in the 1940s. At its heart was a dispute about whether the positive sciences should underpin reconstruction efforts, or whether other ideas based on the subjective experience of space had validity. This dispute tells us much about the diverse ways in which movement is conceptualised in architecture and planning. Specifically, in the examples below, we will see how, in urban planning, movement through the city can be considered in terms of the pedestrian’s experience, but it can also be considered in terms of mathematics, particularly in terms of Newtonian mechanics and statistics.

The limitations of science

Better to understand the nature of the dispute between Sheffield’s planners, we might consider Edmund Husserl’s critique of the positive sciences. In his final (unfinished) book, The Crisis of European Sciences, which was written between 1934 and 1937 and published posthumously,2 Husserl attempted to show that the scientific attitude is a product of history, by charting the emergence of ideals of objectivity and rationalism in European philosophy.3 He admired the achievements of science, but was concerned that the world as described by the sciences does not reflect our actual experience. Galileo was identified by Husserl as the originator of the modern scientific approach to nature, and he wrote of ‘Galileo’s mathematization of nature’.4 Galileo’s innovation was to conceive of the world as ‘a mathematical manifold’,5 as if nature’s secrets were written in a mathematical code that could be deciphered through scientific investigation. Husserl observed that the ‘mathematization of nature’ had continued into modern times, so that ‘numerical magnitudes and general formulae’ became the centre of interest in all ‘natural scientific inquiry’.6 For Husserl, Galileo was ‘at once a discovering and a concealing genius’.7 On the one hand, Galileo discovered ‘mathematical nature’ and ‘the methodical idea’.8 On the other, this ‘mathematical nature’ can ‘be interpreted only in terms of the formulae’.9 Nature, as described through mathematical formulae, does not reflect our actual experience of the world.

Husserl distinguished between ‘morphological essences’, for which there can be exemplars (such as ‘cat’ or ‘government’) but which are not defined in mathematical terms, and ‘exact essences’, which are ideals that can be only approximated in reality and which are mathematical (such as straight lines and perfect circles).10 As exact essences are ideals, they are not given to perception but are conceived in the mind. For worldly phenomena to be made the subject of scientific enquiry, they must be described in ‘exact’ terms, that is, in terms of precise measurements or statistics. This necessarily requires some degree of translation from the morphological to the exact, in a process that Husserl called ‘idealisation’,11 and means that all aspects of the world that cannot be quantified are beyond the scope of scientific enquiry. Consequently, the world as described by modern science is unlike the world as experienced, in that it consists of idealised forms of reality, devoid of all morphological essences. However, as Husserl noted, all too often the descriptions of the world put forward by the sciences are purported to be ‘the true world’.12 The limitations of the scientific approach are unacknow -ledged, and the gap between the world as described by science and the world as experienced is forgotten. Husserl referred to this as: ‘the surreptitious substitution of the mathematically substructed world of idealities for the only real world, the one that is actually given through perception, that is ever experienced and experienceable – our everyday life-world’.13

Husserl wanted to counter this error by providing an account of the sciences that placed them in the broader context of everyday lived experience, in which the scientific viewpoint is incorporated as just one possibility among many. As will be demonstrated below, Husserl’s critique of the sciences helps us to understand the possible source of the dispute between Sheffield’s technical officers that started in 1942. Some of those involved in the dispute seemingly prioritised mathematical descriptions of the world over subjective experience.

Urban planning in Sheffield prior to 1942

The two planning schemes at the centre of the dispute between Sheffield’s planners had a complicated genesis.14 Sheffield started as a small market town, before industrial development caused it to expand rapidly from the eighteenth century. By the early twentieth century, the city centre consisted largely of densely populated housing intermingled with polluting workshops. Concerns that overcrowded and insanitary conditions would have an adverse effect on people’s health prompted a number of initiatives, including the appointment, in 1936, of Sheffield’s first planning officer, Clifford Craven.15 Among his first tasks was to draw up a planning scheme for the city centre to address the perceived need to separate housing from industry, and to ease traffic congestion, which was becoming a problem as car ownership increased.16 A draft version of this planning scheme was complete by September 1939,17 but the outbreak of the Second World War in the same month temporarily brought planning activities in the city to a halt.18 Craven was sent into the armed forces, and his staff were reassigned to Air Raid Precaution work, leaving only the chief assistant to handle any urgent work.19 Town planning only became a priority again following a severe enemy air raid on the city in December 1940, which caused extensive damage to Sheffield’s centre.20 Within weeks, the city council was inundated with applications for permission to rebuild,21 and it was decided that Craven was needed back in his post as planning officer on a full-time basis.22

The Diagonal Road Scheme

Although damage to Sheffield was not as severe as in parts of London, questions were raised within the city council as to whether the bombing had invalidated Craven’s planning scheme. The council looked to national government for guidance, and, in April 1941, the city was visited by the Ministry of Health’s chief town planning inspector, George Pepler. He asked the city council to consider whether the bombing had created the opportunity to create a better town, and reiterated the sentiments of Lord Reith, minister of works and buildings, to ‘plan boldly but not recklessly’.23 It soon became apparent that Craven was reluctant to make major changes to his planning scheme.24 The amended plan, submitted to the council in late 1941, featured only minor revisions, intended to take advantage of the bomb damage.25 It became difficult for Craven to maintain this position when, in March 1942, efforts to revise the scheme were formalised with the creation of a Special Sub-Committee on Review of Planning, as an offshoot of the city council’s town planning committee.26 Further pressure came later that year when, in the absence of any visionary new proposals from Craven, the city architect, William Davies, submitted his own proposal to the city council.27

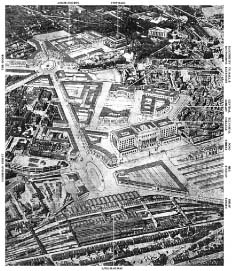

Davies’s proposal, known as the Diagonal Road Scheme, envisaged a new boulevard cutting diagonally across the existing street grid, from the city’s main railway station to the Moorhead shopping district (Figure 2.7.1). A new, 350-foot diameter ‘circus’ was to mark the termination of the new road at the Moorhead. Another new road led from the Moorhead circus to the existing City Hall, aligned with the centre of City Hall’s classical façade. The scheme proposed new buildings, including law courts, a technical college and municipal offices. Essentially Beaux Arts in style, the Diagonal Road Scheme featured formal devices such as axial ordering, regularly shaped spaces and use of symmetry. The aim was to create a sequence of spaces to form ‘a dignified and direct approach, of easy gradient’, from the bus and railway stations to the city centre, thereby enhancing the pedestrian’s experience of moving through the city.28 The formal devices employed were intended to be appreciable by a person ‘on the ground’; Davies emphasised the importance of the vistas to be created, particularly that of the City Hall from the Moorhead circus.

Figure 2.7.1 The Diagonal Road Scheme

Source: Sheffield will look like this when re-planned, Sheffield Star, 20 October 1942, p. 3. © Sheffield City Council

The competition

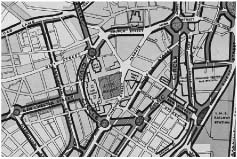

Craven gave his support to Davies’s proposal,29 and Sheffield City Council approved the Diagonal Road Scheme in December 1942.30 However, it did not receive universal support. In particular, the city engineer, John Collie, claimed it ‘falls so short of providing what I considered to be essential for traffic requirements’.31 During the following months, as the technical officers worked to find a way to incorporate the Diagonal Road Scheme into a larger city plan, relations between the officers became so strained that the city council decided they could no longer work together. To resolve the problem, the city council arranged a competition between the planning officer, the city architect and the city engineer, in which an adjudicator would select a single planning scheme for the city centre.32 Herbert Manzoni, Birmingham’s city engineer and surveyor, was given this role.33 The three technical officers submitted their proposals anonymously in January 1944,34 and, in May, Manzoni reported that he had selected a winning entry,35 which was later revealed to be the work of John Collie, the city engineer.36 After some modifications, the winning scheme was adopted by the city council in June. It superseded all previous planning schemes, including the Diagonal Road Scheme.37 Craven resigned his post, and Collie was appointed as planning officer, in addition to his responsibilities as city engineer.38 After further amendments, Collie’s scheme was published in 1945, in a book entitled Sheffield Replanned.39 It included images of a new Beaux Arts-style law courts building, terminating a grand boulevard, to be called New Chester Street. Closer inspection reveals that the 1945 plan did not follow the Beaux Arts model: New Chester Street would not have connected two civic spaces, its other end leading to nothing more than a traffic roundabout. Unlike those in the Diagonal Road Scheme, the civic spaces proposed under the 1945 plan were ill defined and irregular (Figure 2.7.2). The pedestrian’s experience was generally neglected. In particular, passengers leaving the railway station were expected to cross a busy arterial road, before entering a subway tunnel with no visible exit (Figure 2.7.3). This contrasts sharply with the dignified route from railway station to city centre that had been envisaged in the Diagonal Road Scheme.

Figure 2.7.2 Detail of the plan published in 1945, showing the proposed Civic Circle ring road encircling the city centre and the proposed New Chester Street leading to a new law courts building

Source: Town Planning Committee, Sheffield Replanned. © Sheffield City Council

Figure 2.7.3 The proposed exit from Sheffield’s main railway station, as seen from the station roof

Source: Town Planning Committee, Sheffield Replanned. © Sheffield City Council

The geometry of moving bodies

So, if the 1945 plan was not intended to enhance the pedestrians’ experience, what were its author’s aims? According to a statement in Sheffield Replanned:

The initial requirement is to produce a road layout which . . . relieves . . . traffic congestion, and removes the danger created by uncontrolled traffic in heavily used streets. Any street layout which does not achieve this has failed in its primary purpose, however attractive or symmetrical it may appear on plan.40

Providing for motor vehicles was given priority over and above the arrangement of space. Motor cars first appeared in Britain in around 1894,41 and by 1938 there were nearly 2 million licensed cars on Britain’s roads.42 This increase led to traffic congestion. For example, in 1938, approximately 1,750 vehicles per hour were recorded as passing along Sheffield’s High Street during peak periods.43 The rising number of cars produced more traffic accidents. The approximately 1,700 road deaths nationally recorded in 1919 more than quadrupled to 7,343 by 1934.44 To address these problems, from 1930 onwards, the Ministry of Transport issued guidance on the design and layout of roads.45 This recommended that fast-moving through traffic be separated from slower-moving local traffic and from pedestrians. One consequence of this segregation was that roads for through traffic, the so-called arterial roads,46 could be designed following different formal rules from those applied to local roads, to enable the arterial roads to accommodate vehicles moving at relatively high speeds. A car travelling through a bend experiences a centrifugal force, which can cause it to skid or overturn.47 The speed of the car and the radius of the curve determine the magnitude of this centrifugal force, and it was understood that this force could be reduced by ensuring that every bend had a constant radius of sufficient magnitude.48 An additional recommendation was that transition curves, which do not have a constant radius, be introduced between straight and curved sections of road, so that the centrifugal force would be applied to the car gradually.49 The resulting geometry, featuring large-radius curves and clearly visible in the drawing for Sheffield Replanned, is different from that used in Beaux Arts planning. It was also believed that, within cities, arterial roads should be laid out using the ‘wheel and spokes’ model of city planning, in which radial roads were bisected by ring roads, so that through traffic could be directed away from the city centre.50 The Ministry of Transport used financial incentives to promote ring-road schemes in the 1930s,51 and Manzoni selected Collie’s scheme precisely because it was the only one to propose a ring road around the immediate centre of the city.52

Conclusion

A number of possible causes for the dispute between Sheffield’s technical officers can be identified. Town planning was not yet fully established as an independent discipline, and Craven seems to have been held in low regard by his colleagues. Prior to Craven’s appointment, it was the city engineer’s responsibility to prepare planning schemes, and the dispute was partly about who should wield this power. It was also a dispute between architects and engineers, for Davies, as city architect, found his plan rejected by Collie, city engineer. For Collie, the imperative was to find a solution to the problems caused by the rising number of motor vehicles, an issue the Diagonal Road Scheme failed to address. However, this concern does not explain why Collie’s team so effectively ignored the pedestrian’s experience in devising the 1945 plan. Perhaps the dispute between Sheffield’s technical officers is best characterised as a disagreement about which forms of knowledge have validity. Collie and his team prioritised an approach to planning based on mathematically verifiable knowledge, such as statistics on traffic density and accident rates, and the forces acting on a vehicle moving through a bend. By contrast, the Diagonal Road Scheme was based on principles that had their origin in the classical world, not in modern science. Collie and his team seemingly did not accept the (morphological) principles on which the Diagonal Road Scheme was based; moreover, they neglected the pedestrian’s experience. Arguably, this is because the rationalistic approach lends itself to design for the movement of motor vehicles. By contrast, the bodily, sensual experience of moving through the city as a pedestrian is not easily described in mathematical terms.

Notes

1 See, for example, Gordon Cherry and Penny Leith on the authors of the Advisory Handbook published by the Ministry of Town and Country Planning in 1947 (HMSO 1947); Cherry and Leith 1986, p. 96.

2 David Carr, in the Foreword to Husserl 1970, pp. xvi, xviii.

3 Ibid., pp. 15–16.

4 Ibid., p. 23.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid., pp. 47–8. Also see p. 45.

7 Ibid., p. 52.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid., p. 53.

10 Husserl 1982, p. 74.

11 Husserl 1970, pp. 24–8.

12 Ibid., p. 51.

13 Ibid., pp. 48–9.

14 For a more detailed account of these events, see Alan Lewis (2013) Planning through conflict: Competing approaches in the preparation of Sheffield’s post-war reconstruction plan, Planning Perspectives, vol. 28, pp. 27–49.

15 Special Committee re: Town Planning and Civic Centres (1936) First report, 19 June, with City Council Minutes [hereafter cited as Special Committee, Report]; Special Committee (1936) Third report, 28 August.

16 C.G. Craven (1938) Sheffield: The example of the replanning of a central area, Local Pamphlets, vol. 5, no. 3, 042 SQ, Sheffield Local Studies Library, 2.

17 Sheffield City Council (1939) Town and Country Planning Act 1932: Draft Sheffield (Central) Planning Scheme. Local Pamphlets, vol. 5, no.14, Sheffield Local Studies Library.

18 Sheffield City Council (1939) Minutes of the Council, 6 September, Sheffield Local Studies Library [hereafter cited as City Council, Minutes].

19 Planning officer in letter to city engineer, 10 November 1939, City Engineer’s Files, CA655(1), Sheffield City Archives [hereafter cited as CA655(1)]; Special Committee (1941) Eighteenth report, 21 April.

20 Philip Healy, ‘Sheffield at War’, in Binfield et al. 1993, pp. 243–5.

21 Letter from city engineer to town clerk, 31 December 1940, City Engineer’s Files, CA655(16), Sheffield City Archives.

22 Special Committee (1941) Eighteenth report, 21 April.

23 Ibid.

24 Raids worry planners, but 1939 Sheffield Plan still valid, Sheffield Telegraph, 17 February 1942, p. 3.

25 Special Committee (1941) Twenty-second report, December.

26 Town Clerk in letter to members of the Special Sub-Committee on Review of Planning, 20 March 1942, Minutes of the Special Committee re Town Planning and Civic Centres, 21 November 1938, CA674(54), Sheffield City Archives [hereafter cited as CA674(54)]; Special Committee (1942) Minutes, 16 March, CA674(54).

27 Handwritten notes on the first meeting of the Special Sub-Committee on Review of Planning, 27 March 1942, CA674(54).

28 City architect (1942) City of Sheffield – Proposed revision of the Sheffield (Central) Planning Scheme, 19 October, CA674(54).

29 Planning Officer (1942) City of Sheffield – Proposed revision of the Sheffield (Central) Planning Scheme, 19 October, CA674(54).

30 City Council (1942) Minutes, 2 December.

31 City engineer in letter to town clerk, 8 July 1942, CA655(1).

32 Report of the Special Sub-Committee on Review of Planning, 13 November 1943, City Engineer’s Files, CA655(2), Sheffield City Archives [hereafter cited as CA655(2)].

33 Ibid.

34 Report of the Special Sub-Committee on Review of Planning, 8 November 1943, CA674(54); for confirmation of city engineer’s submission see letter from city engineer to town clerk, 1 February 1944, CA655(2).

35 Minutes of the Special Sub-Committee on Review of Planning, 20 May 1944, CA655(2). Manzoni actually submitted his own planning scheme to Sheffield City Council, based on John Collie’s scheme.

36 Minutes of the Special Committee re Town Planning and Civic Centres, 12 June 1944, CA655(2).

37 Manzoni plan approved in principle, Sheffield Telegraph, 8 June 1944, p. 3.

38 Town Planning Committee, 4 August 1944, Minutes of the Council, Sheffield Local Studies Library [hereafter cited as Town Planning Committee, Minutes].

39 Town Planning Committee (1945) Sheffield Replanned (Sheffield: Sheffield City Council).

40 Town Planning Committee, Sheffield Replanned, p. 36.

41 Webb and Webb 1913, p. 240.

42 Hass-Klau 1990, p. 44. The precise number was 1,944,394.

43 Traffic figures for Central Area, 7 December 1943, CA655(2).

44 Hass-Klau 1990, pp. 40, 44.

45 See summary of the guidance issued by the department in HMSO 1943, p. 3; also see HMSO 1930.

46 The term ‘arterial road’ has been used in different ways by different writers. In particular, the Ministry of Transport, in the 1946 publication Design and Layout of Roads in Built-Up Areas, used the term to refer to ‘Roads serving the country as a whole, or a region of the country, and linking up the main centres of population’. Roads in built-up areas were labelled ‘through roads’. I use the term ‘arterial road’ here because it evokes the circulation of blood in the human body, and so encapsulates the notion of a road as a conduit for circulation, rather than a multipurpose space.

47 Batson 1950, p. 41.

48 Edric Tasker (1928) Superelevation, Proceedings of the Institute of Municipal and County Engineers, vol. LIV, 17 March: 1135; H. Criswell (1930) A simple treatment of superelevation, transition curves and vertical curves, as used on the Great North Road in the County of Rutland, 1925/26, Proceedings of the Institute of Municipal and County Engineers, vol. LVI, no.15, 21 January, p. 820.

49 Criswell, Simple treatment of superelevation, p. 826.

50 Cherry 1974, p. 25.

51 City engineer’s account of meeting with Mr Knight of the Ministry of Transport, 15 July 1937, City Engineer’s Files, CA655(3), Sheffield City Archives.

52 Minutes of the Special Sub-Committee on Review of Planning, 20 May 1944, CA655(2).