THE INFLUENCE OF THE “MILIEU” ON ARCHITECTURAL CRITICISM

Introduction

Criticism is an activity with a very broad cultural meaning whose purpose is to interpret and provide a context. It can be understood to be a hermeneutic that reveals the origins, relations, significances and essentials. The difficulty of passing judgement continues to increase in today’s age of uncertainty and questioning.

(Montaner 1999)

The critical question in this chapter, is the influence of the “milieu” on criticism and building performance evaluation. We will discuss how an understanding of the milieu as a concept is necessary to shed light on the contexts criticism seeks to explicate. In this particular case, the concept of milieu is understood to fall within the definition proposed by the geographer Augustin Berque: “as the relationship of a society to its environment” (Berque 1994). To define what is meant by criticism, we refer to an article in the Encyclopaedia Universalis (Devillard and Jannière 2007) and to an anthology of articles of criticism (Deboulet et al. 2008) in which the authors question beyond the criticism, the critical positions as well as the role of the criticism of architecture’s evolution.

Since the end of the 1980s, according to Hélène Jannière, criticism in specialized literature has become an “object of discussion” and, more recently, “an object of research,” both in France and internationally (Jannière 2008). “The need to reconstruct critical tools,” when faced with the “weakening of doctrines and reference points in architectural trends,” is perhaps one of the reasons for this interest (Jannière 2008).

In this chapter, we shall begin by identifying the respective distinctions and fields of criticism and POE/BPE (post-occupancy/building performance evaluations). Then, by underlining the need to take into consideration the reference milieus of the analysed building projects, we shall discuss the value of developing a hermeneutic approach to criticism and evaluation. Finally, “in today’s age of uncertainty,” we shall question whether the paradigm of sustainable development, adapted according to the milieus, could provide new reference points on which criticism and evaluation could be based. This ultimately facilitates an effort to develop common guidelines, which are important to re-establish the absent or weakened “reference points” mentioned by Jannière.

Architecture to envision changes for the future

What is criticism? An analysis of recent publications in France reveals the difficulty of defining it, and moreover, of specifying its origins. Valérie Devillard and Hélène Jannière, in their article for the Encyclopaedia Universalis, noted two schools of thought with regard to the historiography of criticism: one sees its beginning with the Renaissance and expressed through theoretical investigations and treatises; and the other envisages its beginning more with the publication of the first architectural journals towards the end of the eighteenth century, such as “1789 in Germany,” “1800 in France,” and their chroniclers (Devillard and Jannière 2007).

In the first case, the question was whether the premises of criticism should be based on the development of theoretical thinking and the existential distancing of mankind from its surrounding world; as science supplanted religion, there was less and less mysticism surrounding the natural world, and a more empowered feeling of man as having absolute dominion over it. In the field of architecture, the Renaissance is viewed as a specific moment that saw the birth of modern architecture when, similar to Man’s drawn distinctions between himself and the world he emerged from, the Architect started self-identifying as being distinct from the craftsman.

In the second case, by associating criticism with the development of academic and trade journals, criticism could then be partially linked to the “crisis of the unified world as developed by classical tradition” (Montaner 1999: 126). The evolution of techniques and the discovery of other cultures through journalism resulted in a multiplicity of choices and, in the absence of standards, a move toward eclecticism. In the eighteenth century, the search for universal values began to erode at the same time that convictions of beauty and proportion were linked to physiological phenomena. The journals and other media provided information, commentary, and judgment concerning these changes and directions.

The two schools of thought mentioned by Devillard and Jannière represent a foundation for criticism. However, several authors underline the singularity of the work carried out by the critic given that the contents are quite different from a large number of other texts and doctrines. These cannot be assimilated with other types of writings on architecture or magazine articles.

For Pierre Vago, director of the Revue Architecture d’Aujourd’hui from 1932 to 1947, criticism cannot be reduced to “research” or “theoretical dissertations,” even though it demands “the existence of judgment criteria based on reference data.” Criticism “is more than general, historical, sociological, philosophical or aesthetic studies,” even if it requires “a deep and wide-ranging understanding of all aspects of architecture.” Similarly, it cannot correspond to “a subjective and superficial opinion” (Vago 1964–65). According to the position held by Bernard Huet, chief editor of the Architecture d’Aujourd’hui magazine from 1974 to 1977, one should not confuse “criticism and the distribution of more or less complementary information.” According to him, “a journalist can be a critic” but “a critic should never be regarded as a journalist” (Huet 1995).

With regard to these assertions, the citation highlighted at the beginning of this chapter by Joseph Maria Montaner also expresses the role of criticism: “to interpret and provide a context,” to offer “a hermeneutic that reveals origins, relations, significances and essentials.” Faced with an architectural project, whether or not built, the critic proposes “an analysis, explanation, and appreciation in accordance with both general and specific data” (Vago 1964–65). To place the context and the process leading to the development of an architectural work into perspective, the critic can base himself on the social sciences that developed considerably throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, the critic, in order to contextualize a work and evaluate its meaning and interest, cannot just base himself on objective data. He assumes a position by making judgments with regard to the architectural works that he observes. In this sense, the POE/BPE can provide solid foundations on which to make judgments. However, as underscored by Pierre Vago, judging the value of an architectural work requires “a general culture and a vast historical and technical understanding.” This implies, “virtually on a day-to-day basis, to be aware of what is being said, written, drawn, invented or constructed in the world over a period in which everything is in constant change.” It is then necessary to have “the capacity, in the glowing heart of this cauldron of ideas, to pick out the lines of force and constants on which a conviction can be based” (Vago 1964–65). In this manner, the POE/BPE make it possible to check and quantify proposals, compare performances, and to allow architectural criticism to express changes in culture and the capacity of architectural works to be representative of this cultural context.

Why are hermeneutic approaches to milieus necessary?

While the role of critics consists partly of evaluating the contexts of the works and their potential for making the latter clearer, one of the difficulties lies in experiencing them in the milieu within which they are developed, i.e. without simply projecting one’s own culture and one’s own milieu when making judgments. In other words, to understand these milieus, it would seem essential to take into consideration the various types of relations between societies and individuals and their surrounding world. These relations depend on the cultures, the periods, the geographies, and the level of development of the societies. They also influence the way societies are lived in, the way the environment is perceived, and, as a result, the architectural choices that are made. The elucidation of these ties and their contribution to the design process imply the use of a hermeneutic approach by the critic that will assist him in understanding the foundations of the architecture through the designer’s intentions, and the milieu in which it is built. While some of the questions raised on an international level go beyond national borders, the manner in which they are understood and resolved varies according to the local milieus. At the same time, although a critic must be able to analyze a building while taking its milieu into consideration, he should also be able to envisage its meaning while abstracting the particular milieu.

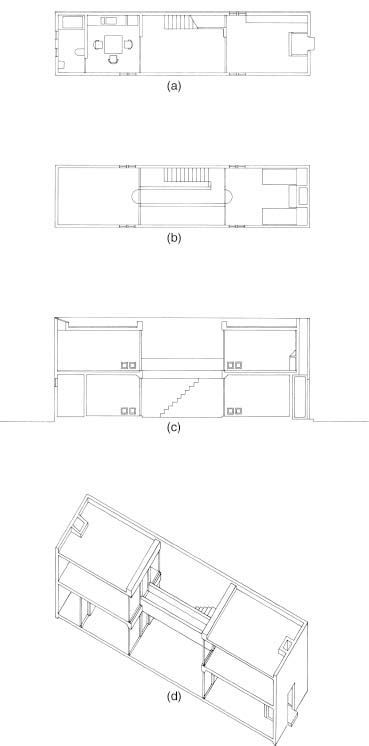

To understand these necessities, let us for example look at the Azuma House by Tadao Ando which was built on an approximately 3.30 m × 10 m plot in the Sumiyoshi district of Osaka in the middle 1970s (Figure 9.1a–d). The simplicity of this building, entirely constructed from raw concrete, with a closed façade on the street side, and forming three identically sized spaces around a central courtyard, sent a clear message from the architect: to insure that the inhabitants and people in general retain links with natural elements. Despite the modesty of this building, the force engendered by the simplicity of the layout and the architectural choices helped his message acquire international status.

However, if one were to provide a detailed criticism of this building and go beyond a cursory reading, it is essential to clearly understand the architect’s way of thinking and the perception of Japanese towns in the 1970s whose chaotic nature at that time was judged to be generally negative. Faced with this urban situation and at the beginning of his career, Tadao Ando explained that it was impossible to retain the idea that housing units face nature, and to keep the traditional relationship that the Japanese have always maintained with their environment. His intention was to re-establish this relationship, but in a contemporary manner. To achieve this, he built architectural prototypes intended to be generators of emotions, within which inhabitants would find themselves in contact with a “nature made abstract,” the “wind made abstract,” the “rain made abstract,” and the “sun made abstract,” all through the architecture.

FIGURE 9.1 Azuma House by Tadao Ando in Osaka: (a) floor plan level 1; (b) floor plan level 2; (c) cross section; (d) isometric

Source: Tadao Ando.

Deciphering Tadao Ando’s intention and architectural mechanisms thus requires a hermeneutic effort from the critic who is obliged to understand the meaning that this architect gives to the concept of nature, as well as to that of the living space, and more generally, the architectural elements he uses. This means making reference to Japanese tradition, as well as a clarification of the large number of influences linked to his design approach (Nussaume 1999). For example, while Tadao Ando uses raw concrete walls, floors, and ceilings, his fundamental desire is that they should be invisible in order to let the space express itself. To achieve this, his finished concrete has a glossy, smooth texture that creates an effect of massiveness in the unconscious of the inhabitants, while also offering a sense of considerable depth in the spaces inside his buildings. That way, confronted with the environment of Japanese cities where it now no longer seems possible to open up buildings, Tadao Ando combines the value of the presence of the walls, while at the same time, he attempts to have them disappear.

Without this understanding of the architect’s intentions, it is impossible to make a deep critical analysis of his works. When it comes to what he judges to be a “superficial comfort,” with which one might agree or disagree, they undoubtedly have considerable meaning in a Japanese environment. Carrying out this type of hermeneutic approach proves itself necessary. It also applies to the POE/BPE that should take into consideration the milieu of the architectural works. This would facilitate judging the validity of the architect’s intentions, and it would assist the criticism by making them clearer.

Can the paradigm of sustainability provide a unified conceptual framework and reference point for criticism?

While books and articles concerning criticism have multiplied over the past few decades, this interest can at least be partially conceptualized as a response to the architectural and societal situation noted at the end of the twentieth century by François Chaslin. This was the period during which he was chief editor at Architecture d’Aujourd’hui. He noted a dual apparent phenomenon: “the collapse of theoretical and philosophical bases of the federal systems that somehow permit the establishment of a classification of architectural trends”; it was also a period that saw the development of theories alongside the growth of a generalized, universal, and transcontinental phenomenon of the “starchitect.” According to François Chaslin, the period was characterized by a generalized intersubjectivity: in order to exist on the stage in the eyes of opinion, architects (and the same applies to artists) must be exposed to the critique of their fellow architects and even their clients. Furthermore, architects must develop their own particular approach, highlight their differences and develop an identifiable style (Chaslin 1990). Faced with a lack of authority or a major principle on which to base his judgments, the critic is simply left with his taste and emotions to discuss trends.

However, we might now ask ourselves if this type of situation is not beginning to radically change. Does the increased strength of sustainable development in terms of both theory and practice give us unique reference points from which to criticize and evaluate architectural, urban, and even landscaping projects? For future generations to develop, we need to affirm the importance of public interest in the various social, ecological, economic, and cultural concerns, thus representing new paradigms for judging architectural works. In a large number of countries, regulations and certifications (e.g. Haute Qualité Environnementale (HQE) in France; BRE Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) in the United Kingdom; Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) in the United States, Deutsches Gütesiegel Nachhaltiges Bauen (DGNB) in Germany, etc.) accompany the growing awareness and reaction to these concerns. The measurement of a building’s environmental impact from its design through to its completion, during its use and even its entire life-cycle forms part of a standard evaluation process that provides the basis for making judgments. POE/BPE type evaluations actively contribute to these measures by offering systematic analyses of construction projects.

Having said that, it might also be worthwhile to question the very concept of sustainable development. Up to what point does it represent a hegemonic doctrine? Could it be considered to represent a risk of systemization insofar as new trends in architecture are concerned? Faced with regulations, including energy regulations, which are increasingly restrictive, professionals are now questioning the often highly technical and expensive methods used to resolve problems raised by sustainable development (Nussaume 2012). A call for the publication of papers, made in 2013 by the Université de Saint-Lucas in Brussels, and called “Architecture and Sustainability: Critical Perspectives,” raised questions concerning these sustainable development paradigms and proposed placing this concept and its influence in perspective. It indicated the need to “focus more on ‘ways’ of conceptualizing ‘sustainability’ with a ‘pluralist imagination’ rather than to search for a universal one-size-fits-all type of sustainability notion.” In this sense, the idea of the call for papers was to think of the theme of sustainability not as a “static notion or a fixed ideal or a set of principles/attributes that can be simply added onto a conventional design process, building or a city,” but rather as “an intrinsic value as a dynamic integrative framework.”

Faced by these questionings and doubts, it is now up to the critic, using POE/BPE as a conceptual base, to explain the directions and the choices made by the designers, without exclusively focusing on “technical aspects,” and by also incorporating the “aesthetic dimensions.” To this end, the critic needs to analyze the contexts of the solutions arrived at by architectural projects to achieve sustainable development by applying a hermeneutic approach that takes into consideration the particular requirements of local milieus and their various social, cultural, economic, and ecological foundations (Nussaume and Perysinaki forthcoming).

Conclusion: criticism, a directional compass for a world in constant change

The acceleration of our understanding in fields such as social sciences and the development of POE/BPE now allow us to better analyze contexts, and the design processes for architectural, urban, and landscaping proposals. Nonetheless, the world continues to change and both techniques and needs are constantly evolving. Consequently, faced with the transformation of territorial contexts, the expectations of inhabitants, lifestyle concepts, and ways of regarding the city are all subject to new paradigms. Confronted with changing problems, the role of designers is to find ways in which to meet the needs of programs and assure levels of technical and spatial requirements, as well as question their future development and find new paths generated by these changing requirements. With regard to this dynamic, the POE/BPE framework represents “safeguards,” but it is up to the critic to evaluate the proposals in accordance with the values of the new directions proposed by the works that he judges.

The incorporation of sustainability, depending on the needs of society, is currently a key issue which can lead toward a common direction between criticism and POE/BPE. To achieve this, critics need to be able to estimate the values of the proposed changes, that is, to put into perspective the proposals made by the architects concerning the paradigm of sustainable development and to take into consideration the diversity of the milieus. If this is not done, criticism and POE/BPE risk simply being tools leading to the homogenization of buildings and landscapes, thereby representing undifferentiated ideas.

References

Berque, A. (ed.) (1994) Cinq propositions pour une théorie du paysage. Seyssel: Champs Vallon.

Chaslin, F. (1990) “Un état critique.” L’architecture d’Aujourd’hui 271. Reprinted in A. Deboulet, R. Hoddé, and A. Sauvage (eds), La critique architecturale: Questions – Frontières – Desseins. Paris: Les éditions de la Villette, 2008.

Deboulet, A., R. Hoddé, and A. Sauvage (eds) (2008) La critique architecturale: Questions – Frontières – Desseins. Paris: Les éditions de la Villette.

Devillard, V. and H. Jannière (2007) “Critique architectural.” Encyclopaedia Universalis. http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/critique-architecturale/ [accessed August 4, 2013].

Huet, B. (1995) “Les enjeux de la critique.” Le Visiteur 1. Reprinted in A. Deboulet, R. Hoddé, and A. Sauvage (eds), La critique architecturale: Questions – Frontières – Desseins. Paris: Les éditions de la Villette, 2008.

Jannière, H. (2008) “Débat sur la critique 1980–2000: Typologies, Frontières, Autonomie.” In A. Deboulet, R. Hoddé, and A. Sauvage (eds), La critique architecturale: Questions – Frontières – Desseins. Paris: Les éditions de la Villette.

Montaner, J. M. (1999) Extract from Arquitectura y critica. Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, coll. GG, Basicos. Reprinted in A. Deboulet, R. Hoddé, and A. Sauvage (eds), La critique architecturale: Questions – Frontières – Desseins. Paris: Les éditions de la Villette, 2008.

Nussaume, Y. (1999) Tadao Ando et la question du milieu. Paris: Éditions le Moniteur.

Nussaume, Y. (2012) “Pour une architecture vernaculaire ‘d’avant-garde.’ ” In O. Vadrot (ed.), Gilles Perraudin. Dijon: Presses du réel.

Nussaume, Y. and A. Perysinaki (forthcoming) “Critical Perspectives on Sustainable Development: Reading the Pillars in the Architectural Design Process of Wang Shu.” In Architecture and Sustainability: Critical Perspectives – Generating Sustainability Concepts from an Architectural Perspective (preliminary title). Brussels: Sint-Lucas Architecture Press.

Vago, P. (1964–65) “La critique architecturale entre carcan et utilité.” L’architecture d’Aujourd’hui 117. Reprinted in A. Deboulet, R. Hoddé, and A. Sauvage (eds), La critique architecturale: Questions – Frontières – Desseins. Paris: Les éditions de la Villette, 2008.