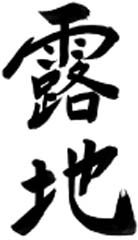

Anthropological perspectives on ritual are often based on the assumption that ritual can be described as an act that differentiates the sacred from the profane.1 A paradigm of how architecture and landscape can be used to produce a state of enlightenment can be found in the ritual environment of the tea garden, as developed for the Japanese tea ceremony. An important component is its connection with the teachings and beliefs of Zen philosophy, for Zen is integral to the essence of the philosophy of tea, in that it finds the ‘conception of greatness in the smallest incidents of life’.2 Through the heightened significance and consciousness applied to one’s actions, the profane act of taking tea is transformed into one of spiritual significance. The way of tea, chado (Figure 3.4.1), is an act of meditation and enlightenment revealing the harmony, respect, purity and tranquillity within.3 Nischke states that:

The more consciousness that is introduced into one’s actions, the more graceful they become. Thus what was usually referred to as the tea ceremony became a meditation, what was known as the tea garden or tea arbour became a temple.4

Zen rejects the world’s outward complexities and embraces an appreciation and awareness for the smallest incidents of life, which can be defined by the notion that, ‘the holy is the ordinary, the sacred is the profane’.5 Zen’s main discipline is that of the attainment of enlightenment, which the Japanese refer to as satori. It is through a wider understanding and awareness of the intricacies of the everyday social routine and mundane acts performed that enlightenment can be achieved.

The tea ceremony, chanoyu, is intricately connected with its setting, and this relationship is fundamental to the understanding of the way of tea. Within the ritual of chado, we are confronted with a complex series of actions and symbolic gestures, which culminate in the realisation of the sacred experience. Anthropologists often view ritualised actions taken as ‘thoughtless action’,6 which can be defined as, ‘routinised, habitual, obsessive, or mimetic – and therefore the purely . . . physical expression of logically prior ideas’.7 This method of analysis is referred to as the ‘thought–action dichotomy’, which suggests that ritual action is without conscious thought and is merely learned behaviour. When considering the way of tea from this position, chado demonstrates that it is, in fact, only through the integration of conscious thought with action that enlightenment can be achieved. Any suggestion that these two aspects are distinct within the tea ritual is ineffectual, for, in Zen, experience and expression are one.

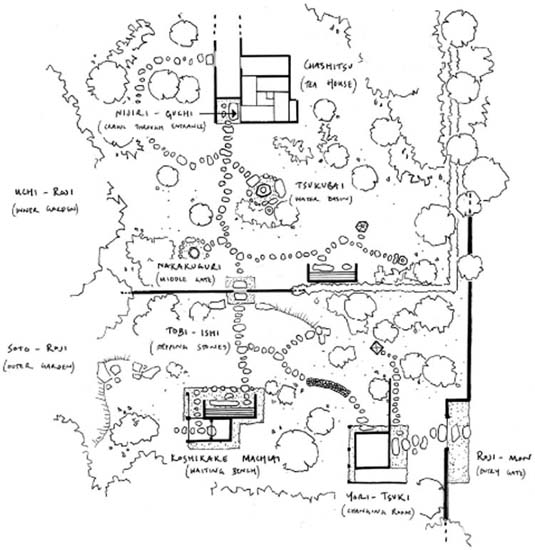

Figure 3.4.1 Plan of the double garden and tea house, showing the necessary buildings and important middle gate

Source: After plan in Keane 2009, p. 199

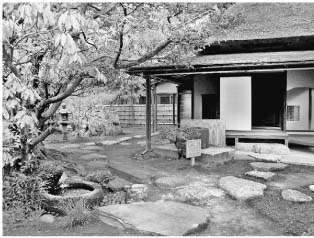

The symbolism and philosophies embedded within the tea house, chashitsu, and the tea garden, chaniwa (Figure 3.4.1), are vital in the creation of an enhanced mindfulness of one’s self and, thereby, the achievement of enlightenment. The elements within the tea ceremony and its ritual environment are embedded with symbolic devices that impact upon the ritual body. The fundamental feature that achieves this is the transitional route, or roji (Figure 3.4.3), which leads from the profane outer world to the inner sanctum of the tea house (Figure 3.4.2). The journey to the chashitsu is designed to increase the participants’ awareness and

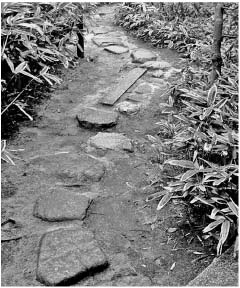

Figure 3.4.3 Tobi-ishi, the stepping stones that draw attention to your gait

Source: Photograph by Chris Hill

consciousness of each action performed. Everyday activities such as walking, eating and drinking, which one would normally perform almost unconsciously, become elevated to a heightened state of awareness generated by the arrangement and devices used within the ritual setting. This feature of the tea ceremony is directly linked to Zen ideologies, fundamental to the creation of the art of tea, in that, ‘the more conscious we are of our daily activities, the more conscious we become of ourselves’.8

A defining element for the ritual environment of the tea ceremony is the emphasis placed upon the threshold. Doors and gates punctuate the progression of spaces leading to the tea house and increase appreciation of the transition from the profane to the sacred. In Japanese Gardens: Right angle and natural form, Nitschke goes on to suggest that, ‘the more barriers that have to be passed on the way to the soan, the tea arbour, the more sacred the site appears’.9 Addressing ritual and sacred space, Eliade considers the threshold in depth, identifying the significance of this device in separating the sacred from the profane. The symbolic emphasis contained leads him to conclude that the ‘threshold is the limit, the boundary, the frontier that distinguishes and opposes two worlds – and at the same time the paradoxical place where these worlds communicate, where passage from the profane to the sacred world becomes possible’.10

The first threshold encountered by guests on arrival at the roji-mon is the entry gate, which marks the entrance into the sacred realm of the tea garden. As a signal that the host is prepared and anticipating their arrival, the gate is left partially ajar, a subtle device repeated throughout the journey to the tea house to signify each barrier and the associated invitation to pass through it. The guests proceed to the yori-tsuki, the changing room, where they remove their outside clothes and change into the ceremonial plain kimono, split-toed socks (tabi) and sandals (yori), supplied by the host. This simple act once again signals a subconscious transition into the sacred realm and prepares the participant for the ritual experience. After they have changed, the guests move to the koshikake machiai, the waiting bench, where they sit and contemplate the garden, admiring the flowers and scroll displayed. Once the host has prepared the tea house and is ready to begin the ceremony, he or she walks from the chashitsu, through the garden to the koshikake machiai to summon the guests. The host then returns to the tea house to make the final preparations and leaves the gates to the tea house, the naka-kuguri and nijiriguchi, partially ajar in anticipation of the guests’ arrival. The principal guest leads the group in a single-file formation through the chaniwa towards the naka-kuguri gate. The chaniwa is divided into two main parts, the inner and outer roji. The area of the chaniwa situated between the roji-mon and naka-kuguri is referred to as the soto-roji.

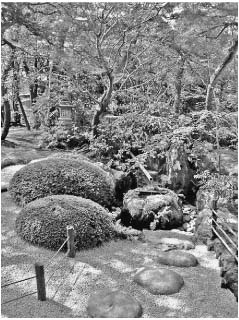

The soto-roji is the mediator between the profane world and the inner sacred space of the chashitsu. The aesthetic qualities of the separate areas of the garden are extremely distinct from each other, with the soto-roji more elaborate in design, with rich foliage and planting. The stone pathway, nobedan, is generally more direct, and the structure of the paving stones is more ordered, than those within the uchi-roji. The temporal nature of the roji is dramatically important to the preparation of the ritual body and mind. Nitschke suggests the notion of ‘experiential time’ within the tea garden as a device with which to create the ritual environment and goes on to say that one can ‘expand space by increasing experiential time through the reduction of speed and the obstruction of movement’.11 Through the introduction of winding pathways, stepping stones and obstacles such as the naka-kuguri, the tea garden forces the participants to slow their movement and become more conscious of each step taken. The time spent progressing through particular areas of the garden also subtly increases the perceived distance from the mundane outer world and thereby enhances the ritual experience of the participant. In addition, the roji is used as a device to cleanse ‘the dust of the world from one’s heart and mind’.12 In The Way Of Tea: A symbolic analysis, Kondo suggests that, with the symbolic nature of ‘the purity, freshness and naturalness of the garden, the transfer of symbolic qualities intensifies’.13 This sensory cleansing is a primary aspect of the intimate connection between Zen and chado, and it is the outer roji’s main purpose to cleanse the senses and remove the defilements of the outer world, creating purity, sei, and tranquillity, jaku, within the ritual body. Rather than denying sensory stimulation, the tea garden and tea house intensify sensory experience through an amplified focus upon such simple acts as contemplating the setting of the tea house, smelling the rich foliage of the garden, listening to the boiling water in the kettle, tasting the tea and handling the utensils. In the Hagakure: The book of the Samurai, Nakano Kazuma states that, ‘when thus all the sense organs are cleansed, the mind itself is cleansed of defilements’.14

Transition from the soto-roji to the uchi-roji is achieved through the middle crawl-through gate, the naka-kuguri. The naka-kuguri is a stand-alone timber wall or fence, with a pitched roof and small, window-like opening. This opening is placed approximately half a metre above the ground, with large ‘trump stones’, or yaku-shion, either side of it, upon which the guests stand as they enter. The gateway measures approximately 1 metre square, so that the guest is required to squeeze and bow while passing through into the inner sanctuary of the garden. This use of threshold is a powerful device to inculcate humility and reverence in the guest, as demonstrated through the chado principle of kei. Upon entry into the uchi-roji, the atmosphere of the garden changes dramatically (Figure 3.4.4). The vegetation is extremely basic – primarily mosses and simple foliage. The aesthetic qualities of this area follow wabi sabi, the appreciation of the imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. It is through this concept that jaku, the chado principle of tranquillity, is manifested. Wabi can be defined as a ‘quiet, sober refinement or subdued taste’, whereas sabi is the ‘beauty or serenity that comes with age’.15 When related to the inner roji, the subdued and refined qualities of the arrangement and planting all contribute to this sense of an ‘aesthetic of poverty’.16

Figure 3.4.5 Tsukubai, close-up, with water ladle: all the implements must be beautiful and worthy of contemplation

Source: Photograph by Chris Hill

Figure 3.4.8 Roji

Source: Drawn by Masashi Minagawa Source: Drawn by Masashi Minagawa Source: Drawn by Masashi Minagawa

A fundamental element of the design of the chaniwa as a whole is the consideration of juxtaposition. The contrasting aesthetics and ambience felt within the different spaces enhance the ritual environment of the outer and inner roji. This is demonstrated by Nitschke in the notion that, ‘what is to be empty must first be filled’,17 which suggests that, to achieve the meditative qualities of the way of tea, as evident within Zen doctrine, the consciousness of the transition between the profane and the sacred is vital. Therefore, in contrast to the soto-roji, which focuses on a purification of the ritual body, the uchi-roji’s primary function is to increase the consciousness of the guests’ movements and ritual body. Devices such as the stepping stones (tobi-ishi) (Figure 3.4.6) and water basin (tsukubai) demonstrate this effectively. The tobi-ishi lead the guests from the naka-kuguri to the entrance of the tea house. The stones are arranged in a haphazard formation to elevate the basic act of walking to one of heightened consciousness, which enhances the connection between the ritual body and the natural surroundings of the roji.

The final gesture enacted by the guests before entering the chashitsu is the ritual purification performed at the tsukubai, a stone water basin (Figures 3.4.7 and 3.4.8). Tsukubai appear at numerous religious sites across Japan and are used to ritually cleanse the hands and the mouth prior to entering a sacred site or building. In this situation, the chado principle of purification, sei, is once again demonstrated, as the oral and haptic senses are cleansed of contamination. It can be suggested that, within the symbolic nature of ‘the purity, freshness and naturalness of the garden, the transfer of symbolic qualities intensifies’, and Kondo goes on to identify that, ‘the ritual ablution with water not only washes away the “dust of the world”, it also metonymically transfers the qualities of water – freshness and purity – to the persons of the guests themselves’.18 The tsukubai is further used to increase the consciousness in the simple act of washing and the actions taken to do so. Tsukubai literally translates as ‘the place where one has to bend down’, and it is this bowing motion that induces the impression of humility and awareness of one’s self.

To enter the tea house, the guest must first pass through the final threshold, the nijiri-guchi, a small, crawl-through entrance no more than a metre in height and width. The nijiri-guchi limits the movement of the participant and acts as a device ‘to increase one’s consciousness of one’s own body, and in addition . . . requires everyone to bow and be humbled, regardless of social status in the ordinary world’.19 Through this simple device, the transition from the rich nature of the garden into the simple, tranquil interior is emphasised dramatically. The psychological effect upon the guest is fundamental, and Nitschke illustrates this through the summation that, ‘what one wants to enlarge, one first reduces experientially’.20 The door is left partially ajar once more, to signal that the host is ready for the guests to enter. The principal guest enters first, removing his sandals, and places them on the stone adjacent to the entrance. The guests follow, with the final guest shutting the door firmly behind them to close off the inner sanctum of the tea room from the outer realm of the garden. The sound of the door closing signals to the host that the tea ceremony can begin.

Considering the ritual of the tea ceremony itself, it cannot be interpreted as a single, defining moment; rather, it is a combination of its individual parts and the relative consciousness that these elements induce in the participant, for, ‘by its precise orchestration of sequence and the interrelations among symbols in different sensory modes, the tea ceremony articulates feeling and thought, creating a distilled form of experience set apart from the mundane world’.21 The stages that a participant of chado is led through are precisely orchestrated to provide an intricate sequence of ritual experiences. It is a system of symbols and devices that enable the cleansing of the senses and an increased mindfulness of the self, achieved through a complex combination of mechanisms. It is through the juxtaposition of formality, distinction of the sacred and profane, an intensification of sensory perception, heightened awareness of movement, connection of the ritual body and environment that ultimately culminate in an enhanced consciousness of one’s self.

‘One approaches not a sacred object or space, but oneself; and now the most holy self is the fully transparent or aware one.’22

Notes

1 Eliade 1959.

2 Okakura 1956, p. 52.

3 The tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522–91) set these four terms as the key principles of chado. He is attributed with defining what is considered to now be the ‘way of tea’.

4 Nitschke 1993, p. 76.

5 Ibid., p. 73.

6 Bell 1992, p. 19.

7 Ibid., p. 19.

8 Nitschke 1993b, p. 150.

9 Ibid., p. 153.

10 Eliade 1959, p. 25.

11 Nitschke 1993, p. 35.

12 Sen 1979, p. 3.

13 D. Kondo (1985) The way of tea: A symbolic analysis, Man, New Series (Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute), vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 287–306, p. 301.

14 Suzuki 1973, p. 281.

15 Freeman 2007, pp. 22–3.

16 H. Plutschow (1999) An anthropological perspective on the Japanese tea ceremony, Anthropoetics, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 8.

17 Nitschke 1993, p. 3.

18 Kondo 1985, pp. 287–306, p. 301.

19 Nitschke 1993, p. 75.

20 Ibid., p. 37.

21 Kondo 1985, pp. 287–306, p. 302.

22 Nitschke 1993, p. 75