THE PERFORMANCE OF BUILDINGS, ARCHITECTS, AND CRITICS

Introduction

Buildings have to perform, accommodating the needs of inhabitants and accomplishing fundamental tasks like keeping out the rain or holding in the heat or cooling. Likewise, the architects who design buildings and the critics who assess them have to perform, meeting their professional responsibilities in the case of architects as well as garnering the attention of their audience in the case of critics. These various roles can seem at odds with each other. Some architects in the Howard Roark mold and some critics in Oscar Wilde fashion act as if concerns about the performance of a building are beneath them. At the same time, some experts in building performance sound like philistines when they dismiss the aesthetic concerns of architects and critics as a waste of time. Those polarized positions misunderstand what unites all three: their performance.

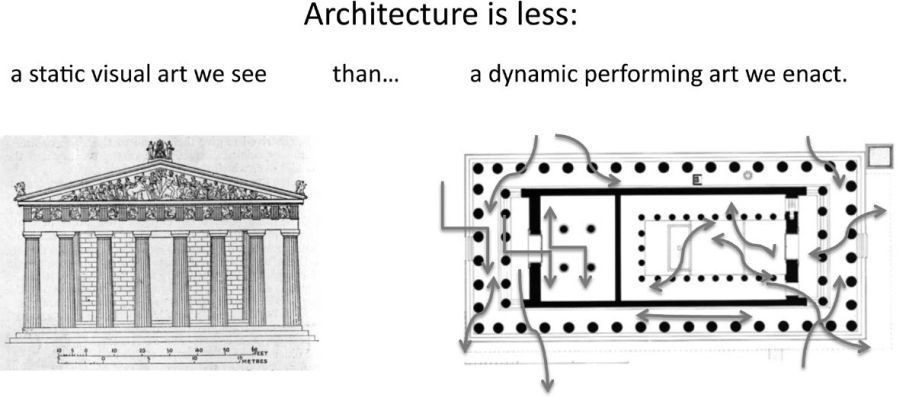

That misunderstanding stems, in part, from a tradition of seeing architecture as a visual art. That tradition has led architects and critics to focus on the form, space, and materials of a building, often assuming that it functions in the same way that artists and art critics assume that a painter knows how to apply paint correctly and so nothing needs to be said about it. That assumption changes, though, in light of the technological advances and increased complexity of buildings, causing us to view architecture not as a visual, but instead as a performing art (Figure 7.1). As in a theatrical, musical, or dance performance, the work of everyone involved in it matters: the performers, but also the director, set designer, sound engineer, costume crew, and so on. Like the performing arts, architecture also relies on the work of a project team – not just the architects, but the consultants, contractors, clients, inspectors – all of whose performance matters to the end result. And like the performing arts, architecture creates an experience for all who engage in it, and its success or failure at least in part depends on that.

Including architecture in the performing arts seems timely, as thinking about what constitutes performance has greatly expanded over the last several decades. The field of “performance studies” emerged in the 1970s, combining the traditional performing arts with social sciences like anthropology, sociology, and political science, and its practitioners study everything from religious rituals to community celebrations to political protests to workplace protocols as performances (Turner, 1986; Schechner 1988, 2002; Carlson 1996). The literature in performance studies almost never mentions architecture except as the backdrop to these other kinds of performances, and so plenty of opportunity exists for the architectural discipline to join this conversation.

FIGURE 7.1 Architecture is less …

Source: author.

A few have recognized that opportunity. Books like Architecture: A Performing Art (Andrews 1991) and Performative Architecture: Beyond Instrumentality (Kolarevic and Malkawi 2005) have connected architecture and performance, although they range from an explication of one architect’s own buildings to a diverse collection of essays based on a conference.

The performance and movement of users has also informed theories of space in popular architectural discourse, most notably in Bernard Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcripts (Tschumi 1995). In general, though, architecture has remained disconnected from the discipline of performance studies, which makes almost no reference to our field in its literature or core concepts. In this chapter, I hope to make that connection by drawing on concepts developed in performance studies to understand how we might design, evaluate, and critique buildings in new and more integrated ways.

Architecture as performance

What changes when we conceive of architecture as a performing rather than a visual art? It shifts our attention away from thinking of a building as an aesthetic object created by an architect toward inquiring into how it came to be, how many people engage with it, and how it changes over time, much as we would the performance of a play or musical piece. The role of the building evaluator and critic changes as well. A building becomes not something to look at and judge, like a painting, but instead something to experience and assess on its own and in comparison with other work, as we might a drama.

Perhaps the greatest change comes in valuing the work of everyone involved in architecture. Viewing architecture as a visual art has led to an over-emphasis on the work of the design architect, with very little if any attention paid to the large teams of people who design, detail, and construct a building and not enough attention paid to how the building performs after completion in terms of its operation and inhabitation. Unlike most of the visual arts, the performing arts remain a collective and collaborative activity that has a life long after the playwright, composer, and choreographer have completed their work, with the continual reinterpretation of its meaning and purpose by those who perform and experience it. The same holds true for architecture, which of all the arts remains one of the most collaborative and most expensive, with all of the people involved in it deserving of recognition and their work, worthy of assessment.

Not everyone plays the same role in the performance of architecture. Architects remain the instigators of work and the ones who orchestrate its design and construction much as a conductor or director would do. The inhabitants of a building play a role similar to that of the audience in a performance, experiencing the production over and over and responding to it in subtle ways and altering it in the process. And the evaluators and critics of a building, like those in the performing arts, serve to capture those responses and assess the meaning of what they have seen and heard, benchmarking that against other performances and situating the work in the history of the field, to current thinking in the discipline, and to the ideas and values of a culture or community.

Performance studies has identified several ways of thinking about what it means to perform, each of which has something to offer architecture. I will look at three of these conceptual frameworks, and connect them to the design, evaluation, and criticism of buildings (Bell 2008).

Mimicking, making, and moving

Aristotle viewed performance as a kind of mimesis or mimicking of life, which we experience in order to better understand ourselves (Aristotle 1952; Goffman 1959). In modern times, theorists like the anthropologist Victor Turner have argued that performance involves “poiesis,” the Greek word for making, in the sense that we make or enact our culture as we perform (Turner 1982). Others like the ethnographer Dwight Conquergood have likened performance to “kinesis,” the Greek word for moving, arguing that when we perform, we challenge cultural norms and move culture forward in the process (Conquergood 1992).

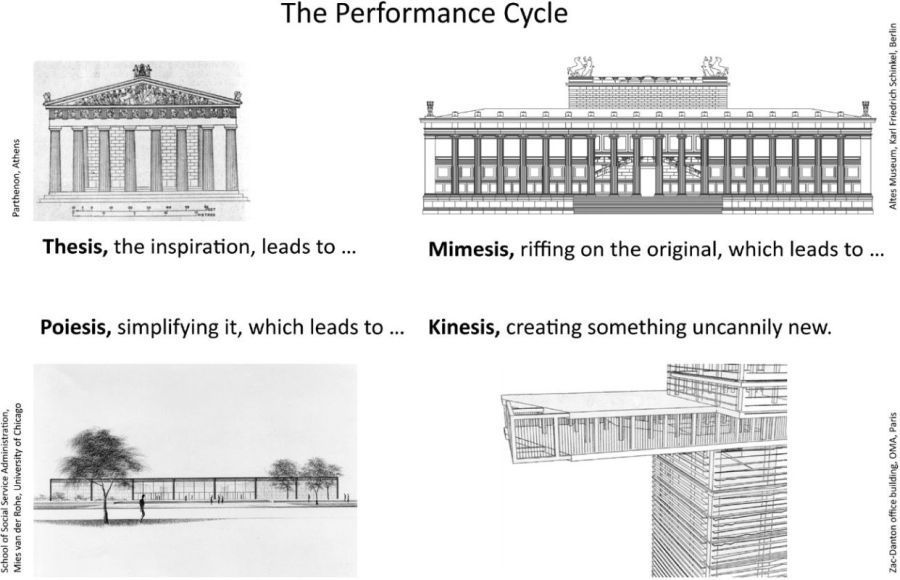

Those ideas about performance have also played out in architecture (Figure 7.2). Most architects prior to the twentieth century, for example, largely engaged in a kind of mimesis, mimicking the styles of previous buildings in incremental and evolutionary ways. Over the last century, poiesis and kinesis came to characterize architecture much more, with the modern emphasis on the making of architecture and on architecture showing how it was made, as well as on originality of architecture, moving the field forward by breaking with the past.

Architectural education has followed a similar path. Most students begin with imitation (mimesis), referencing the work of those who have come before them and to some degree mimicking the ways of thinking and speaking that characterize the discipline. As students become more proficient, they begin to make more original contributions to a field (poiesis) and in some cases, make a discovery or frame an argument that moves the entire field forward (kinesis).

That same framework also applies to the roles that architects, critics, and building evaluators play. Those who evaluate the performance of buildings do so through a kind of mimesis: gathering data about an extant building, comparing those findings to established benchmarks, and assessing them in terms of the existing literature. They do not mimic, but they do adhere closely to what we know in order to understand a new situation. And while they are not mimes, they do attend to the subtle ways in which bodies inhabit and interpret space.

The designers of buildings perform a kind of poiesis. Even when influenced by the past or an existing context, architects almost always make something new: physically, in the form of a new building or renovation, and culturally, reflecting their own ideas as well as those of clients and communities. Like the ancient poets who first engaged in poiesis, architects obviously play a central role in the making of architecture, but rarely do they fully understand the meaning of what they have made.

FIGURE 7.2 The performance cycle

Source: author.

That role falls to the critics, who operate through kinesis: assessing where the field is moving, what has helped or not helped it move forward, what constitutes a move backward, and what all of this movement means. Critics, in that sense, serve as intellectual kinesiologists, studying the movement not of bodies, but of minds, not just the thinking of individual creators, but also the collective mind of the discipline and the larger culture.

Like actors in a play, the architect, critic, and building evaluator have complementary roles to play in the performance of architecture. One does not trump the other nor can one occur without the other, any more than a play can run without all of its characters interacting on an equal footing. All three roles – mimesis, poiesis, and kinesis – contribute to successful performance, and that remains as true for architecture as for theater, music, and dance.

Enabling, knowing, and judging

A performer needs to have the ability, knowledge, and judgment to perform and here, too, performance studies has something to offer architecture. The ability to perform goes beyond talent and technique of the performer; it includes the ability of people to attend a performance. In that sense, a performance constitutes a community of all of the people involved in it – the performers and audience as well as everyone else responsible for some aspect of putting it on. And in the process, a performance can create a group identity or challenge assumptions of the community of people involved (Bell 2008). A building does the same. The ability of those who design and construct it remains just one part of an ongoing process in which the building enables – or inhibits – others from performing their duties as they live and work.

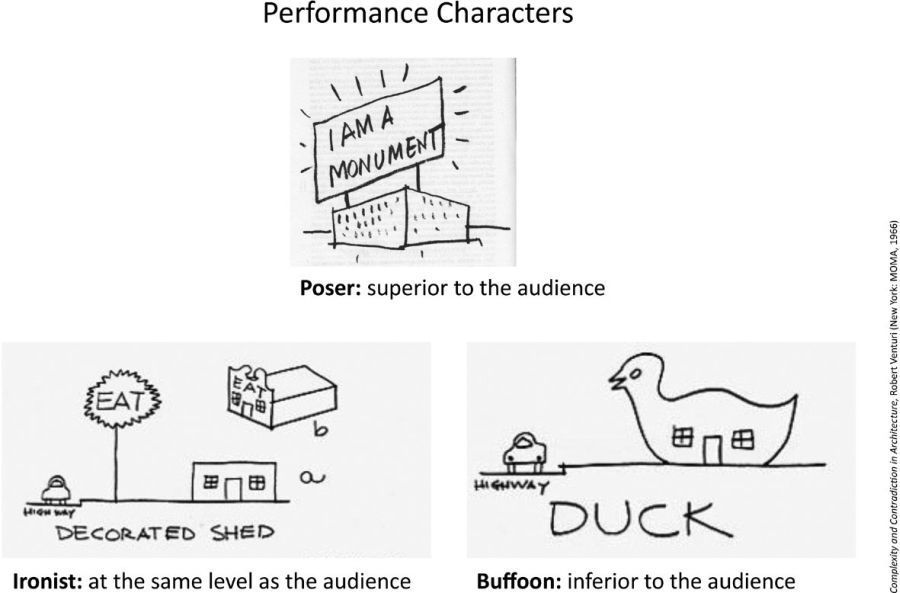

FIGURE 7.3 Performance characters

Source: author.

Performance also involves a way of knowing, a way of learning about others and also about ourselves. This notion of performance suggests that we understand some things only through their enactment, “in and through the body,” as Elizabeth Bell puts it, and through the careful observation of bodies in space. Architecture performs in this way as well. It creates the spaces within which bodies move, relationships occur, and interactions of all sorts happen among people. A building offers not only the setting within which people perform, but also a reflection of how we enact our daily lives.

Finally, performance offers a critical perspective as well. Every performance, in some way, comments upon the world around us and a good performance should leave us questioning our assumptions and imagining new ways of being in the world. Good architecture should do the same. A building never offers a neutral background to the dance of life; every decision made about a building involves a critical assessment of a situation and even when a building makes an attempt at complete anonymity, that in itself serves as a critique of those buildings that don’t.

Architecture always engages all three modes of performance. It enables the people who make or inhabit it, it reveals things about ourselves in the process, and it forces us to make a judgment about it, positively or negatively. Still, different players in an architectural performance may emphasize one mode or another.

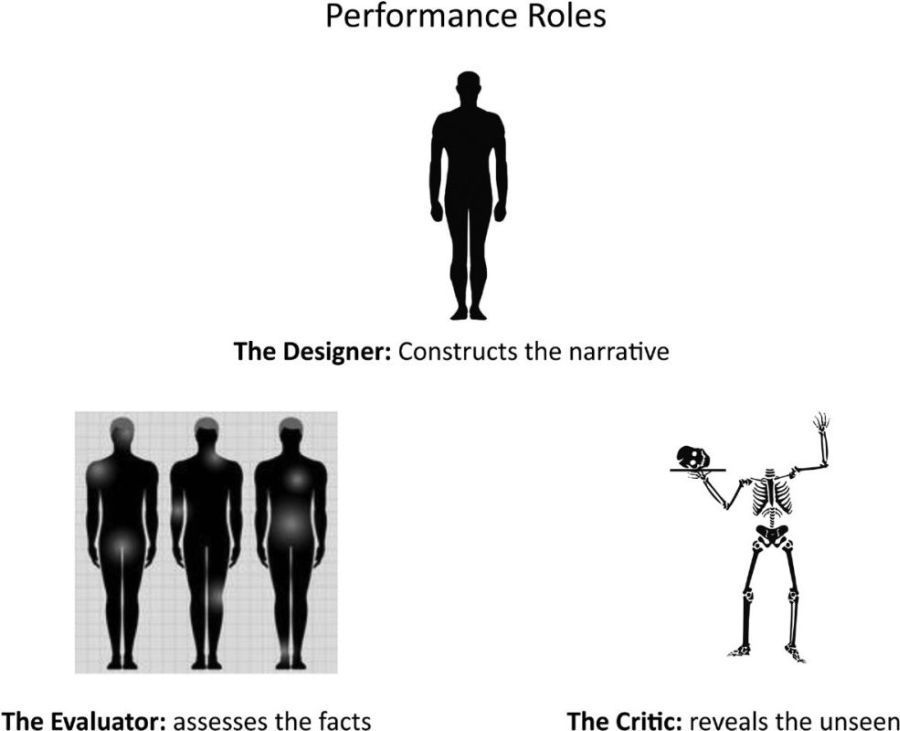

The designer of a building typically serves an enabling role, creating the spaces within which the relationships, identities, and cultures of people play out. The evaluator of architecture, in contrast, often takes the knowing role, concentrating on what we understand about a building through careful observation and precise measurement of its performance. And the critic, in turn, plays the critical role, raising questions about what a building means, about the assumptions behind it, and about what it suggests about the larger world of ideas or things.

The ancient Greeks distilled those three roles into stock characters: the poser who acts superior to the audience, the ironist at the same level as the audience, and the buffoon inferior to the audience (Aristotle 1952) (Figure 7.3).

Explaining, revealing, and story telling

We go to performances for essentially three reasons, to engage in some sort of story, told through words, music, and/or movement that explains or reveals something important about the world. The sociologist Paul DiMaggio has categorized theory in a way that also applies to performance. We have “narrative” performances that tell us how the world works, “covering” performances that explain what the world is, and “enlightenment” performances that help us see the world in a new way (DiMaggio 1995). DiMaggio argues for hybridizing these types and that advice applies to architecture as well. Every building, to some extent, results from a narrative about a situation that reflects what clients or communities face at present and that reveals what they hope for the future. And every actor in the architectural performance – the architect, critic, and building evaluator – have to do this as well, telling some sort of story about what a building is and what it will enable those who inhabit it to do or become.

And yet, here too, everyone in an architectural performance has his or her own part to play (Figure 7.4). The architect has to tell a story about past work in terms of the present commission as well as construct a narrative about how a new design responds to what those who commissioned it wanted. The evaluator of a building, once completed, has to cover as many of the facts about it in order to assess its performance and explain to others what the data show. Finally, the critic has to enlighten others about a building in some way, convincing an audience why it matters and helping people see not just a building, but also the world around them in a new way, fresh with possibility.

Every performance, like every theory, says DiMaggio, is a “social construction after the fact,” a way of understanding or justifying what has happened or what we have done (DiMaggio 1995). That remains true of architecture too. Architects respond in intuitive as well as rational ways to a client’s needs and building’s program and site, and often the story about how and why a design evolved becomes an after-the-fact rationalization of decisions, the larger meaning of which the architects may not fully understand. A different “after-the-fact” quality pertains to the building evaluator and critic as well. Both have to respond to what already exists, the social and physical construction of architecture. And both have to construct a story after the fact to explain what they have found or what they see there, whether it be an explanation about why a building does not work as intended or an argument about why a building does not live up to its aspirations.

If a performance requires all three activities – story telling, explaining, and revealing – the last of the three, though, distinguishes good work from great. We all like a good story and value a clear explanation, but art at its best reveals something fundamental that we haven’t yet realized or something new that we haven’t thought of before. We seek out performances in hopes of finding such revelation, which helps explain why people will go to extraordinary lengths to visit great buildings. Such structures continue to enlighten us in some way.

FIGURE 7.4 Performance roles

Source: author.

A new role for the critic

From that perspective, there exists a hierarchy among the three players we have followed in an architectural performance. While the visual arts have traditionally privileged the architect over all others, the performing arts suggest a different sorting of roles. The playwright and composer, like the architect, play the key role of providing the material that gets performed and as with a theatrical script or a musical score, the architect’s design becomes the basis for all the other action. Likewise, as with a director or conductor, the orchestrator of a building – the person who understands how it all goes together – also plays an essential role. That analytical function, be it of a contractor prior to a building’s completion or a performance evaluator afterward, makes the work a reality and makes it last.

Still, in the performing arts, the interpreters of the work – the actors, musicians, and dancers – tend to get the most attention. They become the “stars” that audiences relate to, in part because the audience members see themselves in or resonate with the performers. In architecture, that interpretive role remains largely unfilled. “Star” architects have tended to fill that vacuum as interpreters of their own work, even though, as the work’s creators, they often don’t fully understand its larger meaning.

This suggests, instead, a new role for the critic, not as someone who just tells a story about a building or just explains what it might mean, but also someone whose interpretations of a building reveal something new about the world around us and about others and ourselves. Such critics have existed in architecture: Jane Jacobs almost single-handedly stopped modern urban renewal and Robert Venturi turned austere modernism on its head (Jacobs 1961; Venturi 1966). But we need many more such critics willing and able to do the same, interpreting the architectural world in some revealing or enlightening way … as I have tried, successfully or not, to do here.

References

Andrews, J. (1991) Architecture: A Performing Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aristotle (1952) Poetics, trans. Ingram Bywater. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bell, E. (2008) Theories of Performance. London: Sage.

Carlson, M. (1996) Performance: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Conquergood, D. (1992) “Ethnography, Rhetoric, and Performance.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 78: 80–123.

DiMaggio, P. (1995) “Comments on ‘What Theory is Not.’ ” ASQ 40: 391–97.

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.

Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Kolarevic, B. and A. Malkawi (2005) Performative Architecture: Beyond Instrumentality. New York: Routledge.

Schechner, R. (1988) Performance Theory. New York: Routledge.

Schechner, R. (2002) Performance Studies: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Tschumi, B. (1995) The Manhattan Transcripts: Theoretical Projects. New York: St. Martin’s Press/Academy Editions.

Turner, V. (1982) From Ritual to Theatre. New York: PAJ Publications.

Turner, V. (1986) The Anthropology of Performance. New York: PAJ Publications.

Venturi, R. (1966) Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. New York: Museum of Modern Art Press.

Following Part I (Introduction), in its exploration of the intellectual history and milestones of modern architectural criticism, the authors of Part II begin to set the stage for this book’s review of emerging methods of inquiry that take “architecture beyond criticism.” In itself, this theme opens up a broad space for fresh interpretation. Lurking beneath each chapter is an historical tension between science and hermeneutics. Aesthetic interpretation of building form and empirical assessment of building performance seem like two incompatible traditions of thought. The question of their convergence could not come at a better time, since the entire industry, theory included, is shifting rapidly toward orientation to objective evidence and data. The chapters, both in the previous Part I and the Parts III–V that follow, try to sort out whether empirical evidence has a place in cultural criticism; whether cultural criticism can effectively engage the technical complexity of environmental systems, both human and natural; and whether between them there could not be emerging opportunities for authentic hybridity, for an improved and integrated or synthetic approach, such as the habitability framework proposed in Chapter 1, among others described in this volume. Allow me to call the convergence of these two distinct vocabularies – one empirical, the other hermeneutical – “built environment criticism.”

Can criticism properly understood accommodate these two estranged intellectual traditions, separated since the mid-twentieth century by what C. P. Snow described as “a gulf of mutual incomprehension” (Snow 1959)? To be sure, the role of the critic is distinct from that of the architect or scientist, different also from the constellation of agents and actors who produce, operate, and occupy buildings. Likewise, the role of the critic is different from that of the scholar for whom architecture and its variegated contexts are targets of design inquiry and research. A critic’s job, Ezra Pound declares, is to “make a personal statement, in re measurements he himself has made … KRINO, to pick out for oneself, to choose. That’s what the word means” (Pound 1934). Dictionaries agree: a critic is “a person who judges the merits of literary or artistic works, especially one who does so professionally”; as Pound notes, it comes from the Greek word krinein, to judge or decide (Oxford English Dictionary 2014). In this context judgment is not juridical, but it often involves moral, ethical, and aesthetic pronouncements, sometimes based on objective evidence, but most of the time based on informed opinion.

Architecture ≈ classical music

Part of the challenge of assessing architectural criticism’s proper role and subject is to stabilize what it is we’re talking about when we talk about architecture. Into this question Tom Fisher introduces a novel swerve that deserves more exercise (Fisher, Chapter 7). His argument for architecture as a performing art puts me in mind of a prescient comment issued by the novelist William Gibson during a presentation at Peter Eisenman’s 1990 Anyone conference. This was the first of eleven such conferences Eisenman hosted in the run-up to the new millennium: “If the people who are currently building nanotechnology and virtual reality have their way with us, I think that what we think of today as architecture will be considered as something like classical music … I don’t think architecture will even be an issue if technology runs the course that it’s currently setting for itself” (Gibson 1991). In the two decades since Gibson offered these remarks, virtual technologies – parametric design, geographic information systems, building information modeling, and product life-cycle management, among other developments – have transformed architecture and the building industry. Suppose in its slowness to adapt to these seismic changes, architecture is indeed heading the way of classical music. What are some of the implications of this analogy?

Gibson, who coined the term “cyberspace,” issued this prediction before a small, select audience of the world’s leading avant-garde thinkers. Gibson seemed to infer that high architecture – physical, permanent, heavy, expensive, arcane, and self-referential – might further reduce to the kind of connoisseurship Aaron Davis references in his Chapter 2. Gibson’s analogy questions high architecture’s relevance, not its integrity, since so long as there is an elite workforce capable of producing and performing classical music, there will always be a small but persistent audience willing to pay to listen to it. Classical music will always count, no matter how small the audience is, likewise highbrow architecture. Wealthy individuals, corporations, cultural institutions, governments, well-resourced arbiters of fashion, and collectors of fine art will always seek some measure of what David Remnick calls “wildness” – “too far enough” (Remnick 2012).

With that said, let’s take Gibson’s analogy at face value – let’s say architecture in fact “goes the way of classical music.” The United States has 117 orchestras with budgets in excess of $2.5 million. This number suggests that the country supports fewer than 12,000 full-time payroll positions to support public demand for the live and recorded performance of classical music, roughly 11 percent of the total number of registered US architects. If architecture goes the way of classical music, assuming comparable rates of attrition, by extrapolation the need for intern architects would reduce from 5,000 per year, the current rate, to roughly 440. If Gibson’s prophecy comes to pass, the market would require about five schools of architecture, down from the current roster of 130 accredited programs. Surviving schools might then assume the role of elite music conservatories, supplying the pipeline for the dozen or so large offices we’ll need to sustain design and produce what Michael J. Lewis calls “swagger building” (Lewis 2002). Needless to say, a reduction in demand of this magnitude might also influence the structure of state regulation.

If such a future leads to the diminution of licensed practice, we therefore might also witness a shift back to vocational training to supply the construction and real estate industries with digital modelers, much the way musicians who train in high school and college supply the market for the much broader and robust popular music industry. These recharacterized programs might become lesser departments of architecture, operating like today’s lesser departments of music, servicing majors who contemplate careers in commercial as distinct from cultural production, in service to real estate developers and contractors. Programs in building information management might likewise proliferate, the twenty-first-century equivalent of “drafting,” delivering to the market a skilled workforce able to manage the virtual modeling platforms that enjoy increasingly wide use in the construction industry. Strictly speaking, building information management needs no regulation, so long as there are professional engineers nearby to oversee building systems, technology, structure, and safety.

If virtual reality has its way, Gibson seems to say, economic forces will either shrink or transform the demand for architectural services, further diminishing the profession’s authority and relevance, further shrinking its public intelligibility, further limiting the number of architects who achieve the status and recognition with which we associate success, and further confining its value to the appetites and budgets of wealthy patronage and philanthropy. As for the rest of the tiny percentage of buildings in the developed world designed by licensed architects, much like commercial songs and soundtracks, they will pass by borne on the wide currents of popular culture, forgettable because trivial. That said, classical music, like art and theater, will still need its few famous critics.

There is not a little merit in Gibson’s prediction, as far as it goes. Twenty-five years later, the profession still lionizes Pritzker laureates and still covets scarce magazine covers, despite the fact that so few architects can expect to see their efforts ever published. Moreover, the global, hyper-democratic space of teletechnology and social media generates and disgorges novelty at a rate that almost precludes lasting recognition. Celebrity still depends on older, slower media – books, magazines, newspapers – which increasingly favor photography and graphics over text, since fewer and fewer members of the profession and the general public read reflectively. Even without industry data to support these trends, the audience for high-style architecture – like the audience for high art and classical music – represents a minuscule fraction of the number of people on this planet who might benefit from architectural knowledge – who, for example, still lack safe, habitable dwellings, workplaces, and neighborhoods, such as the 60 percent of the planet (4.8 billion people) who suffer inadequate sanitation, or the 30 percent (2.5 billion people) who lack any sanitation whatsoever (Hensman 2013).

Despite such discouraging ratios, design fame remains the pinnacle of achievement in both the education and practice of architecture. The aforementioned Pritzker Prize and the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal recognize achievement in building design and building design alone. Not surprisingly, most of architectural criticism, and most academic studio critics, reward objects and their appearance over what Fisher characterizes as their “performance,” though this is a far more appropriate program of evaluation, since in theater and film more people enjoy high recognition for “back of house” technical achievements. The problem is not design in itself; great design will always generate what Stan Allen calls “difference that makes a difference” (Allen 2009). The problem is rather the peculiar way the schools and the profession bind design into practices that habituate criteria for success. About the worst thing you can say about a student of architecture is that he or she isn’t a very good designer, and we see no rush to challenge the values on which critics base anointment and dismissal.

Architecture ≈ design

So what’s partially at stake in the discourse on the future of architectural criticism is the future of the profession. Increasingly, architectural educators argue that we should recast professional education as a foundation for alternative careers in design outside conventional practice and licensure. These educators envision architecture as part of a much larger field of “good design,” spanning the full spectrum of scales, from typefaces to territories. Few advocates argue this perspective more forcefully than Paola Antonelli, curator of art and design at the Museum of Modern Art. Antonelli’s assessment of design’s relationship to government and policy greatly extends its boundaries. She calls for “design applied not as a mere aesthetic or functional tool but as a conceptual method, based on scenarios that keep human beings in focus, with the means consequently allotted in elegant, economic, and organic ways to achieve the imagined goals.” She reminds us that design helped shape empires, dictatorships, and democracies. Her argument suggests that design reasoning applies to social as well as physical morphologies and processes, which by extension expands the integrative properties of architectural problem-solving beyond building form to any number of formal and political problems. Professional and post-professional curricula therefore can serve as the basis for alternative career paths that optimize architecture’s unique understanding of design methodology in fields outside traditional practice, such as marketing, organizational theory, and business management (Antonelli 2011).

Antonelli’s vision offers architecture new horizons of opportunity at a moment of profound technological and economic reorganization. However, the ultimate cost of this expansion may be the protected status of the title “architect,” which though greatly respected within this enlarged domain of practice may eventually pull loose from its weakened professional moorings, leaving what remains of licensure to burnish the identities of culturati and connoisseurs, the one-half-of-one percent wealthy enough to commission mansions, skyscrapers, museums, and symphony halls, with or without concern for design that improves health, reduces carbon, or adapts to changes in program or climate.

With that said, evidence suggests the beginnings of a shift in architectural criticism toward interdisciplinary perspectives. Take for example Places, an august print journal founded in 1983 by MIT architecture faculty, which in 2010 migrated to a website founded by the Design Observer Group, a consortium led by the socially progressive graphic designers Michael Beirut, William Drentell, and Jessica Helfand (Places 2014). The editorial diversification of Places augurs the diffusion of architectural criticism into Antonelli’s expanded field, alongside unregulated design disciplines – for example, graphic, product, and urban design – that practice at both smaller and larger scales. For its part, science has similarly introduced new, hybridized media for a new kind of integrative criticism, best demonstrated in the success of Places’ counterpart, a digital magazine called SEED – catchphrase “science is culture” – that features both short-form criticism covering science’s intersection with an exhilaratingly diverse index of 68 topic areas, blending science, engineering, policy, art, design, and economics within a single, coherent discourse (SEED 2014). Taken together as two examples of true intellectual hybridity, the editorial content of Places and SEED bridges the gulf between design and science. This gap earns further analysis in the parts and chapters that follow, where authors explore the commensurability of criticism and evaluation in our broadened engagement with environments whose boundaries expand beyond architecture in both directions, from the scale of hospital rooms and furniture to the scale of urban parks and cities.

References

Allen, S. (2009) Practice: Architecture Technique + Representation. New York: Routledge.

Antonelli, P. (2011) “We Have Only Begun to Tap into Design’s Real Potential to Serve as a Tool for Policymaking, Governance, and Social Agendas. When Used Correctly, It Can Integrate Innovation into People’s Lives.” SEED Magazine, February 1. http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/on_governing_by_design/ [accessed January 1, 2014].

Gibson, W. (1991) “Text(v)oid.” In Anyone. New York: Rizolli, pp. 162–63.

Hensmen, C. (2013) Keynote presentation. AIA Seattle Data-Driven Design Forum, December 10.

Lewis, M. J. (2002) “The ‘Look-at-Me’ Strut of a Swagger Building.” The New York Times, January 6.

Places (2014) http://places.designobserver.com

Pound, E. (1934) ABC of Reading. London: Routledge.

Remnick, D. (2012) “David Remnick on Bob Dylan.” Radio Silence (radio broadcast, September 4). http://vimeo.com/48856703 [accessed December 24, 2013].

SEED (2014) http://seedmagazine.com

Snow, C. P. (1959) The Two Cultures: And a Second Look. The Rede Lecture, 1959. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1964.