The Scale of Globalisation

What the previous chapters each show, in their different ways, is the complex relationship between architecture, urbanism, cultural identity and globalisation. There can be little doubt that the cities around the Persian Gulf have undergone a process of urbanisation and modernisation over the past few decades; they are clearly not the same places they used to be. But as previous accounts of urban modernisation reveal – with the classic still being Marshall Berman’s All that is Solid Melts into Air – it is far from being an even or consistent process.1 The effects of uneven modernisation around the Gulf have been discussed throughout the chapters of this book. Today there are now the almost tired older centres of development such as Abadan/Khorramshahr or Kuwait City or Dammam; as well as busy newcomers like Manama or Doha or Abu Dhabi or Sharjah, epitomised above all by Dubai; or indeed the places in Iran where modernisation has the most potential to rush ahead in future, including Bushehr, Kangan/Banak, Bandar Abbas, Qeshm, and, above all, Kish Island. In general, the cities on the western Arabic coastline are larger and more central to their own country’s economic and cultural life, while those on the eastern side tend to be far smaller and more marginal within Iran, at least for the present. This final chapter will not attempt to force any simple conclusion, especially given that modernising processes and their effects are still so uncertain in the Persian Gulf. Instead, I will set out some thoughts about the subject of architectural globalisation and also point to new tendencies, drawn from a critical perspective, which can suggest other ways to design for Gulf cities in the years ahead.

From the outset, I should make clear that I am not a fan of the usual definitions of globalisation within architectural discourse. Critics have rightly warned of the danger of treating globalisation as if it were somehow a natural and inevitable process.2 But it seems equally dangerous to portray globalisation as if it were merely a construct of neo-liberal economics which architecture have then to decide whether to ‘react against’, ‘work within’, etc.3 What is needed instead is to find ways of talking about globalisation that do not simply play into the hands of the powerful elites which currently dominate global capitalism – instead, the aim ought to be to pull apart the material and ideological mystifications of globalisation.

19.1 Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in Hong Kong by Foster + Partners (1983–1986)

We have to do this because globalisation, however it is defined, is the crucial transformation of our age. All other issues, including our widespread worries about climate change and loss of biodiversity, follow in its train. Yet it is equally obvious that architecture still has a difficult time in adapting its discourses and practices to suit global conditions. What is often referred to as architectural globalisation often doesn’t have that much to do with it, or else stems from its least interesting or appealing aspects. Instead, there needs to be fresh thinking about architectural globalisation, something I will attempt in this essay by arguing for a change in conceptions of scale away from the dimensions of form and space, to the dynamics of form and space. It is a process already happening through the emerging conditions of globalisation, as will be seen later when referring to some of the architectural initiatives now underway in the Persian Gulf – i.e. in a region of the world, as this book has shown, which offers an exemplar for studying the impact of globalising processes.

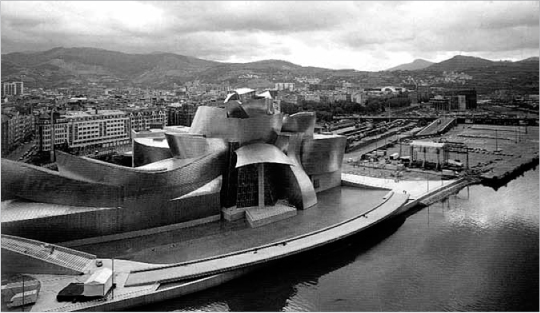

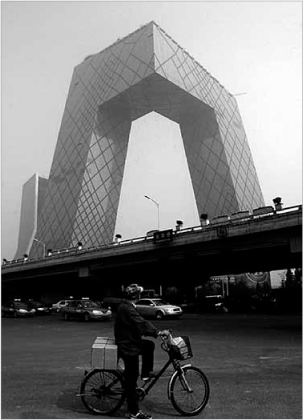

First, however, it is worth spelling out some of the problems with normal views about architectural globalisation. This can be done by considering three canonical buildings: the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank in Hong Kong, designed by Foster & Partners (1983–1986), the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao by Frank Gehry (1993–1997), and the Chinese Central TV Headquarters in Beijing by Rem Koolhaas/OMA (2004–2012). They have often been cited as icons of architectural globalisation from each of the last three decades. Yet in fact they are but part of a far older pattern of dominance whereby a few countries – firstly in Europe and later the USA – held cultural sway over what were regarded as relatively undeveloped or ‘backward’ places. Thus these three iconic buildings exist because of the imposition of supposedly ‘superior’ ideas and values from outside, and thus from above. It is certainly noticeable that none of the buildings picked up anything from engagement with its context that went on to change the subsequent designs of their respective architects in any meaningful way. It is the old pattern of imperialism and colonisation by any other name, once again making a fetish out of the public display of power and wealth.

19.2 Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao by Frank Gehry (1993–1997)

19.3 CCTV Building in Beijing by Rem Koolhaas/OMA (2004–2012)

Rem Koolhaas, the CCTV’s designer, is one of the smartest architects around, and as such is more than aware of that key tactic of the avant-garde, which is to declare a contradictory position to what one is actually doing while also showing one is aware of doing this. Hence we find an astonishingly self-conscious quote from Koolhaas in Der Spiegel when he says:

I have a very hard time with the expression “star architect”. It gives the impression of referring to people with no heart, egomaniacs who are constantly doing their thing, completely divorced from any context …4

And if that were not an astute piece of auto-critique, Koolhaas goes on to talk of the consequences for the ‘star architect’ in designing too quickly for yet another contentious brief in a place they know little about:

… There is less time available for research, so a tendency toward imitation develops. One of our theories is that one can offset this excessive compulsion toward the spectacular with a return to simplicity. That’s one effect of speed.5

From such a statement it is only a step to the empty symbolism of buildings such as the so-called ‘peace pyramid’ in Astana by Foster & Partners, opened in 2006 for the autocratic ruler of Kazakhstan, or Zaha Hadid’s ‘space age’ concoction for the SOHO Galaxy offices in Beijing (2010–2012). If this really were to be the end-goal of architecture after all those millennia of human society, then we might as well pack up and go home. But if we remind ourselves that what Koolhaas, Foster, Gehry, and now Hadid, are up to has relatively little to do with globalisation as such, then there can be another way forward.

19.4 SOHO Galaxy in Beijing by Zaha Hadid (2010–2012)

A similar problem exists in writings about architecture and globalisation. These texts tend to be rather limited in conception, and focus on one particular aspect such as the architecture associated with global finance (Anthony King), the internationalisation of design practices (Donald McNeill), or the possibility of an alternative regionalist approach (Liane Lefaivre and Alexander Tzonis), rather than attempting to write about the subject in a more rounded manner.6 A more in-depth analysis of contemporary globalisation has been published recently by Robert Adam, although his book too approaches the subject from what is an overly specific viewpoint, being largely concerned with how cultural identity can or cannot be expressed visually in architecture under globalising conditions.7

The resulting problem is that when we read accounts of architectural globalisation we tend to find authors lazily falling back onto one or more of the usual myths – one could even call them fallacies – about globalisation. Although each contains a trace of truth, as myths generally do, the net effect is to diminish the discussion of the subject. To tease this point out further, the five common fallacies can be categorised as follows:

1. The economic fallacy: i.e. that globalisation is essentially all about the working of multinational capitalism and its concomitant financial markets, money flows, and digitalised data transfers. This is of course an ideologically driven reification of globalisation which only ultimately serves corporate interests, stripping the term of any broader validity and reducing it to its most utilitarian tendencies. It is an attitude which also beleaguers even much of the best critical writing on globalisation, such as by Joseph Stiglitz or Hardt and Negri.8 And what the reductive economic viewpoint conceals above all is that cultural globalisation is by far the most vital component in the whole process, and indeed happens irrespective of problems with financial flows – as has been revealed during the worldwide recession that began in 2008 and which as yet shows little sign of ending in most countries.

2. The homogenisation fallacy: i.e. that globalisation is about smoothing out everything and creating a single world order, whereas in actuality it is constantly creating new kinds of difference and heterogeneity, and in ways that will never be uniform or consistent. As Henri Lefebvre once remarked, definitively: ‘No space disappears in the course of growth and development: the worldwide does not abolish the local.’9 Hence the dyspeptic vision of global uniformity has to be viewed instead as a symptom of deeper cultural anxiety about social change. Liane Lefaivre and Alexander Tzonis are particularly representative of this condition, for instance having written:

As globalization increasingly enters every facet of our lives, its homogenizing effects on architecture, urban spaces and the landscape have compelled architects to embrace the principles of critical regionalism, an alternative theory that respects local culture, geography and climate.10

As an observation it is totally wrong, of course, and as Mark Crinson and others point out too easily, critical regionalism is an inherently conservative viewpoint in which the original sense of a political critique of capitalism is lost, leaving only backward-looking romanticism.11 One could also voice the same point by taking another quote:

Some fear that the world is coming to dreadful uniformity and monotony. If so, this day is yet far off. At present we may shudder at the terrific, often senseless, variety of it all.12

The only problem is that the quote happens to be over 70 years old! It comes from Richard Neutra, an émigré Austrian architect in the USA back in the 1930s, and could be used word-for-word as a response to the doomsayers today.

3. The origination fallacy: i.e. that it is only about ‘Americanisation’ or ‘Westernisation’, when in fact globalisation is far more precisely defined as the condition that has arisen because of the ending of the post-war era of US hegemony. To many outside observers, America is now a quasi-empire in decline, as can be shown by economic figures: whereas in the mid-1960s the USA was estimated to account for about half of the world’s combined economy, today that figure is only about 25 per cent, and is falling. Although the US still possesses the biggest economy in the world, recent UN data shows that China overtook America in 2010 as the largest manufacturing nation, following a meteoric rise over the previous five years.13 As with Britain a century ago, America is now in the process of being economically eclipsed by other countries, with particularly China, India, Brazil and Russia forging a more complex balance of global power. This is why it is so important to keep in mind a broader historical account of globalisation, rather than sloppily confusing it as being equivalent to modernity, or to post-war American hegemony in the Cold War era. Instead, those might well have been its preconditions, but what we now conceive as globalisation emerged after the ‘Oil Crisis’ in the mid-1970s, along with other early signals of fading US hegemony.14

4. The novelty fallacy: i.e. that globalisation is an entirely new phenomenon, whereas of course it is being built on top of centuries-old structures of world trade and imperial conquest, and if anything is somewhat patched up and shaky. Indeed, the global movement of people seems the normative condition for humankind, and hence concepts of nationality or cultural fixity – as dominated during the age of ‘high’ capitalism – were perhaps more of a blip in history. Even the briefest glimpse at the Taj Mahal or Oxford’s Radcliffe Camera or the Hospital of Santo Antonio in Porto or Le Corbusier’s designs for Chandigarh – to cite just four of the countless examples available – shows that many seminal buildings are designed in complete contrast to indigenous traditions, yet have been welcomed and adopted as belonging to a place. Or to put it another way, if we believe geneticists like Steve Jones, then the mixing together of the global gene pool has always the main driving force for human societies, and modern technological lifestyles simply accelerate the process.15 It this is indeed the case, then the current fascination with multicultural cities and hybrid architecture echoes this underlying genetic trend.

5. The technological fallacy: i.e. that globalisation is driven by trans-spatial technology and thus is essentially about information flows, digital telecommunications, the internet, long-haul air travel, etc. These technologies have even invented their own fictions such as cyberspace or the global internet map. But while these trans-spatial technologies undoubtedly aid the spread of globalisation, again they remain something different. So whenever one hears that globalisation is failing because of technical problems with the internet, such as viral attacks or cyber wars, it is entirely misguided. Technology can only ever be a concretization of existing social relations, never a major driver in itself, and therefore globalisation occurs irrespective of technology. Let us also not forget that technology tends never to be used in the ways it was intended, nor in the end can it offer solutions as such, only different methods of organising things. As David Edgerton usefully reminds us, in general it is older forms of technology which work better.16

Having identified the five fallacies which prevail in normative discourse about architectural globalisation, it becomes obvious that we need a far more dynamic and nuanced formulation. If one looks at other academic disciplines, there has been a more searching effort to define globalisation, thereby revealing aspects that are extremely relevant to architectural production. Here, for example, is a definition from the German social philosopher, Jurgen Habermas:

By ‘globalisation’ is meant the cumulative processes of a worldwide expansion of trade and production, commodity and finance markets, fashions, the media and computer programs, news and communication networks, transportation systems and flows of migration, the risks engendered by large-scale technology, environmental damage and epidemics, as well as organised crime and terrorism.17

Analysed in this way, globalisation is revealed as a complex and intertwined network in which multiple points of influence impact on each other, and these in turn are influenced by interaction with countless other nodes. Globalisation can thus be conceived as a field in which a multitude of actors and agencies are constantly operating, rather than the linear process with unmediated flows of influence under ‘classic’ imperialism. This suggests a cultural model that rejects binary divisions such as centre/periphery, global/regional or global/local – or indeed any notion that a single ethnic group or country can hold some kind of truth which they then ‘diffuse’ or ‘disseminate’ to others via colonisation or other means. Instead, what do exist are complex trans-cultural networks of exchange in which any attempt to posit a hierarchy is futile. The result of all this, as many observers point out, is that the defining basis of globalisation is the hybrid.18 Above all, global hybridity creates and also thrives in a condition which is heterogenic, fluid and fissured.

Hence what architecture requires is a deeper vision of globalisation closer to what Stuart Hall terms ‘globalisation from below’, by which he refers to the mass movement of people across the world and the opening up of cultural practices like architecture at a fundamental level.19 Much of this human movement is of course driven by desperation and fear, and is deeply traumatic and exploitative; it can also be said to do little to alter existing imbalances of power in societies. Yet nonetheless it opens up greater opportunity and hope than existed previously for the majority of the world’s people. Globalisation is therefore not at all synonymous with the tough invisible processes of top-down ‘economic globalisation’ as described by analysts like Saskia Sassen, although such factors are indeed part of it.20 Instead it is the cultural changes deriving from the migration of people and their ideas which offer the greatest creative potential for architecture in a rapidly transforming world. As one example, a few years ago the British building press reported, somewhat excitedly, that a third of people in architectural offices had been born overseas: yet there wasn’t even a flicker of concern – with most believing the figure was probably higher, especially in London. If British architecture can be seen as healthier than ever, which certainly appears the case, to a large extent this is a product of those who were not born British. One only has to look at Zaha Hadid (Iraq) or David Adjaye (Tanzania/Ghana) or Niall McLaughlin (Ireland), and so on, or at buildings by the likes of Herzog and de Meuron (Switzerland), designers of the Tate Modern, to realise just how vital non-Brits are in energising the scene.

What is required is a time-sensitive conception of globalisation that connects us both to ‘deeper history’ and, as far as possible, to futurology. What, for example, will globalised architecture look like in the 22nd century? Here, however, I prefer to draw out the creative potential of globalisation by examining its spatial dimensions, and thereby to question the whole notion of scale. In this regard, it is essential to recall that the term ‘globalisation’ operates both as a reference to a direct observable process that we can see happening in contemporary cities, and at the same time as a cipher or metaphor (in a similar way to the term ‘architecture’). Globalisation possesses many fascinating spatial characteristics, with the most commonly cited being the diminution, indeed erasure, of previous conceptions of distance and time. Yet equally important is the inner dimension which is created by our subjective experience of living in the world. After all, globalisation is also something which occurs inside us as an internalised process as we inhabit our everyday living spaces, and therefore it is not just a big nebulous entity that occurs somewhere ‘out there’. In other words, we experience an interior globalisation. As a historical precursor, Mies van der Rohe observed the emergence of what he called a new kind of ‘global feeling’ in the 1920s. This, Mies noted, was not to do with the vast infinite scientific cosmos of Copernicus and Newton, but rather was happening because mankind was running out of space to expand into, hence a need to expand inwards into our own minds:

This again is a cosmos, but in a new sense we see it as being without astronomical limits. It is a cosmos seen from a human perspective as the living room that we have been assigned as a field related to our own specific powers of knowledge and creation.21

Such recognition immediately poses a problem for imagining the scale of globalisation. We can no longer rely on the vague idea of a balancing out between larger-scale global forces and smaller-scale local forces. We need to think beyond the clichés (i.e. global = big, local = tiny) to devise some more fluid conceptions of scale. In part, my interest in this topic stems from the frequent criticisms by architectural practitioners of the imprecise use of scale by students when drawing using CAD software, since it gives them the ability to morph their designs continuously, thereby sidestepping (or indeed ignoring) the traditional references of standardised architecture scales such as 1:1 or 1:20 or 1:1000. It is a worry that is now being intensified by the advent of parametric design techniques, and by recent tropes of emergence and environment, which are usually backed up by some kind of attempt to explain architecture as a system or network or rhizome, in a post-humanist sense.22 In reaction to these more fluid conceptual schemata, with their seeming preoccupation with complex curvilinear surfaces, many architects seem keen to reassert the principle of fixity of scale as an instinctive mechanism that can give physical form to invisible trans-spatial systems and processes. But although one can understand anxieties about misconceptions of scale, all it really does is to voice deep unease about contemporary cultural changes.

A more productive approach is to unpick the way in which architects have hitherto tried to conceptualise scale. Linked closely to the objectification of dimensional measurement, which began with bodily or musical scales and was then abstracted in Enlightenment tools such as the metric system, by the twentieth century a definite sense had evolved of the hierarchy of different architectural scales and what these meant.23 Eliel Saarinen, for one, declared: ‘Always design a thing by considering it in its next larger context: a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in a city plan.’ Louis Kahn, in his celebrated acceptance speech when receiving the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal in 1971, made the observation that ‘the building is a society of rooms … the street is a room or agreement … [and the] city from a simple settlement became the place of institutions’, positing a clear conceptual difference between each of these scales.24 Advances in astrophysics and magnification/quantum physics were the source for the Eames’ celebrated ‘Powers of Ten’ film in1968.25 Rem Koolhaas was later to repackage the same hierarchical schema – this time using the language of fashion design – in his book S,M,L,XL in the mid-1990s.26 The problem, however, was that a structured belief in categorical differences of physical scale was also introduced into thinking about globalisation through the idea of local-versus-global, with its patently false binary premise. This has created many adverse effects, not least the frequent and banal use of skyscrapers as the grand motif for globalisation, with the current fascination being focussed on the world’s tallest building – the Burj Khalifa tower in Dubai at 828 m high – but with that likely to be overtaken soon.

19.5 Burj Khalifa in Dubai by SOM (2004–2010)

Urban theorists like Doreen Massey or Manuel Castells have long argued that there is always a complex interlinking process, and indeed a wrapping together, of the local and global in every city.27 Yet for some reason this message still hasn’t quite penetrated into architectural thinking. Hence I would suggest that it is better for us now to drop the schemata of local/global, or ‘glocal’, or whichever term, and instead start to conceive of globalisation in terms of an absence of restraints rather than something that possesses any specific scalar properties. If globalisation can thus seen more as a void or vacuum which provides spaces for things to happen in, then differentiated notions of scale collapse, becoming endlessly intertwined and superimposed on each other. As a concept, it seems closer to space-time in advanced physics, or to Deleuzian assemblages, or indeed the highly mutable software of contemporary computer-aided design. It also allows for the fact that there will continue to be endless urban variations across the world, as well as myriad smaller urban variations within every city, and never patterns of fixity. The dropping of the binary terms of local and global also gets us around the impossibility – indeed danger – of trying to define what might be classified ‘local’ or ‘global’ today in a multicultural city like London, or indeed the thorny problem of deciding who can legitimately claim the authority to be able to give phenomena one of these binary classifications.

Crucially, a more fluid approach also enables us to sidestep the ‘big building syndrome’ of starchitects like Foster or Koolhaas, and look with equal if not even more interest at the creative possibilities of smaller or medium interventions as elements of ‘globalisation from below’. What are needed are new constellations of meaning, new groupings, and interlinked research networks to investigate global architectural phenomena. It is also vital to note that small-scale and medium-scale designs probably offer more interesting and vital tools for creative architectural practice, for four reasons:

1. Architectural innovation mostly arises from the faster and subtler inter-changes which happen across different cultures, rather than from within established cultural blocks with their entrenched power structures.

2. The smaller scale of operations and uneven patterns, fissures and fractures made possible today by globalisation also offer more fertile sites and opportunities for inventive design.

3. Buildings can no longer hope to be symbolic or iconic, given that developed societies don’t hold any fixed and readily agreed social meanings; buildings are still of course representational, albeit now representative of the values of ordinary everyday life as opposed to the unique and powerful, as in the past.

4. Small-scale projects can respond more subtly and directly to the ecological consequences of globalisation, especially if ones looks at the issue of social sustainability, which today has become the key design challenge facing any developed society.

With this more critical view of architectural globalisation in mind, the rest of this essay will look at creative possibilities within the architectural and urban conditions of the Persian Gulf – a context described so vividly in the previous essays. The first point to make, when looking at different kinds of architectural practice in the region, is that so far there has been very little exploration of the collapsed-scale view of globalisation that would enable more fluid readings of forms and spaces in buildings. It is noticeable for instance that, just as in the case of Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel and Frank Gehry in their grandiose cultural institutions for Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi, Rem Koolhaas only ever seemed to be thinking at the very largest global scale when producing his design for ‘Waterfront City’ in Dubai.28 OMA’s vast masterplan envisaged an entire new urban district for 1.5 million inhabitants, although due to the economic recession it stands almost no chance of being built. Koolhaas nonetheless set out his design approach:

My goal is to establish a section of the city in Dubai that is a true metropolis. That includes, most of all, a true public space – not the caricature of a public space, meaning shopping malls. I am very grateful to the government in Dubai for the fact that we will have a court there, hospitals and the terminus stations for two subway lines. In other words, this space will have a recognizable identity, ingredients of what characterizes Dubai, but also a real urban life … [which] isn’t lacking, but it is confused. We have a neighborhood there called Deira, which is completely urban. It’s unbelievably dense, mixed, exciting and beautiful – the type of beauty that will probably need our protection soon. In fact we, as city planners, will have to spend more time in the future thinking about how to plan and preserve at the same time.29

His concern to mesh into the existing fabric of Deira, as an older part of Dubai, and thus to reactivate its downtown areas – not through a typical shopping mall, but by street-based mixed-use urban design – echoes the approach of Allies and Morrison outlined by Tim Makower in his essay on the Msheireb project in Doha. Unlike Allies and Morrison, however, there was never any indication from Koolhaas of how the smaller and more intimate details of his Dubai masterplan might fit into, or modify, daily patterns of urban life. OMA’s design for Waterfront City remained at the broad-brush level of urban iconography.

The limitation inherent in conceptualising and designing at a single scale is something which is also all too common among indigenous architectural practices on both sides of the Persian Gulf region. Thus while most of these firms almost always claim to work with existing architectural and urban forms, in reality this is never really done using a fluid engagement with different scales of design. A very well known Arabic architect in the region is Ibrahim Jaidah, the energetic force behind the Arab Engineering Bureau (which has offices in Doha, Abu Dhabi, and Kuala Lumpur). Typical projects tend to be the office towers and luxury apartments found in so much new development in cities along the Gulf’s western coastline. Jaidah claims his approach is to evoke traditional urban motifs while also embracing western-style modernity.30 One outcome is the Barzan Tower in West Bay in Doha – nominated for an Aga Khan Award in 2004 – which meshes together a quasi-Arabic facade at its base and a mirror-glass tower above, in a manner that seems reminiscent of 1980s post-modernism. Elsewhere, Jaidah’s interest in evoking traditional design, while also equipping it with the latest servicing standards, is exemplified in his award-winning Al-Sharq Village and Spa, again in Doha. It is an Arabic-style hotel and resort for wealthy Qatari residents and overseas visitors. Yet this kind of project, of the kind so often validated by the Aga Khan Trust Award, and which fits in well with the demands of culturally conservative clients, is only fixated with visual references to the forms and symbols used in traditional Arabic architecture, never its spatial meanings and relationships. There can also be little doubt that this approach is holding back the emergence of subtler, more hybrid contemporary architecture in the Persian Gulf. A similar limitation applies to the traditional-style housing estate on Amwaj Island in Muharraq, or the Al Zamil office tower in Manama (winner of an Aga Khan Award), or the Novotel Al Dana Resort in Manama (another Aga Khan Award winner), all of them designed by the team led by Souheil El-Masri of Gulf House Engineering in Bahrain.31 Nor is this stasis in design ambition limited to Arabic countries along the Persian Gulf. The same problem is mirrored all too often along the eastern side of the Gulf, where a variety of pseudo-traditional Iranian buildings are being constructed with non-functional wind-catchers and other superficial historical symbols, again squeezing out the possibility of more creative thinking.

This is not to deny that there are younger and hungrier practices appearing on the radar within the Persian Gulf region. X-Architects were founded in Dubai in 2003 by Ahmed Al-Ali and Farid Esmaeil with the express intention of being more critical and innovative in approach, as can be seen for instance in their Xeritown master-plan for a 60-hectare sustainable city in the desert close to Dubai (2007), or on the Ain Al-Fayda National Housing Proposal for Al Ain in Abu Dhabi (2009).32 Furthermore, in a recent issue of Architectural Design, Michael Hensel and Mehran Gharleghi put together a fascinating survey of innovative projects by younger Iranian architects, although notably none of those featured operate in cities along its Persian Gulf coastline.33 Given therefore the stifled quality of so much of the architectural design culture in the Gulf region – a condition which seems entirely at odds with the dramatic globalising changes taking place – the new result is that much of the best new thinking comes from at least some of the western architects who are designing projects for the region. This in itself is perhaps not that surprising, since it accords with my previous observation that innovation takes place more readily at the intersections and crossovers between cultures, and not from within cultural blocks. Soon of course the architects of the Persian Gulf region will be driving the new creative ideas, yet for the moment of cultural transition it appears to be these external agents who are breaking the moulds.

Although the amount of work being done by western practices has declined substantially since economic recession started to bite in 2008, there are notable ongoing activities especially in terms of low-energy sustainable design. Aside from the aforementioned Msheireb project, which is reshaping a sizeable portion of downtown Doha, the most famous is Foster & Partners design for Masdar City.34 This project sits slightly to the south-east of the city of Abu Dhabi, close to its international airport and main university, and in essence is creating a new suburban university quarter. The buildings are focussed on the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology (MIST), which is being run in conjunction with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The project is largely funded by the Abu Dhabi government through various companies set up for the purpose. The initial phase of Masdar City is due for completion in 2015, and is already receiving wide publicity for its mass transportation system, electric cars, emphasis on walkability, low-energy prototype buildings, and extensive use of solar panels and other high-tech applications. However, Masdar can equally be criticised as being an expensive, top-down, government controlled, commercialised approach that has eradicated any genuine sense of experimentation from the equation. If the future of energy-efficient building really needs to have so much money spent on it, then we are left with a real conundrum about how global resources should be used.

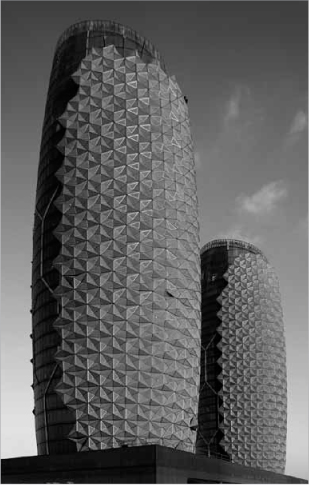

Far more innovative is another major research initiative set up in the rival city of Doha, called the Qatar Pilot Plant; it forms one of the initial stages of the much larger Sahara Forest Project, which hopes to find ways to farm the desert lands of North Africa and the Middle East. The ideas for the Qatar Pilot Plant are coming from an international research consortium with partners in the UK and Norway, including Bill Watts from Max Fordham LLC in London.35 Operational from December 2012, this experimental low-energy centre in Doha is being built on land owned by a leading fertiliser company. Its express intention is to remain as open and flexible and creative in its thinking by incorporating elements such as algae, sea plants, saltwater greenhouses, etc within its integrated system of renewable fuel sources. Already crops have managed to be grown in an otherwise hostile setting. A different attempt to find a more responsive method of energy-conscious design, this time at the level of building detail, is a new environmental technique to shade all-glass office towers which has been devised by Aedas under the lead of its former research director, Peter Oborn36 (see Plate 31). In a new pair of blocks in Abu Dhabi, called the Al Bahar Towers, the office towers are wrapped with a series of aluminium-framed folding screens faced with polytetraflouroethylene (PTFE). The screens are carefully monitored and controlled by computers to open and close in response to the sun’s movement. It transforms what are otherwise standard towers into exquisitely encrusted examples of performance art, in effect by deploying a mechanical mashrabiya screening. At an even bolder sculptural level, the dramatically curvilinear Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies, located in Doha’s Education City, is now being completed on site by the Anglo-Spanish practice of Mangera Yvars. Also part of their scheme is a mosque to serve the wider university campus.

19.6 Al Bahar Towers in Abu Dhabi by Aedas Architects

19.7 Close-up of ‘mashrabiya’ installation on the Al Bahar Towers

19.8 Villa Anbar in Dammam, Saudi Arabia by Peter Barber (1992–1993)

19.9 Entrance pool in the Villa Anbar

19.10 View of chauffeur’s house in the Villa Anbar

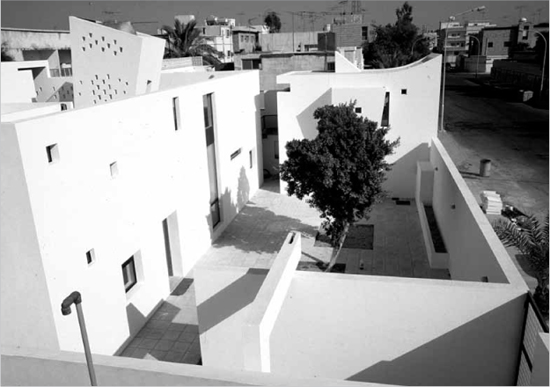

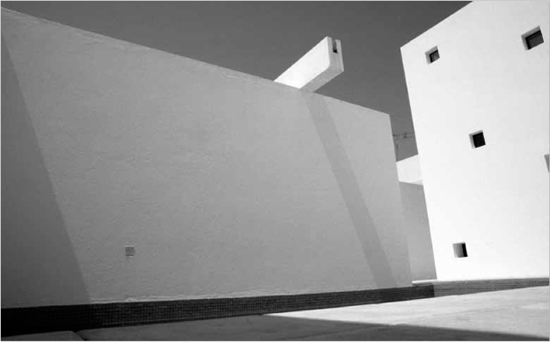

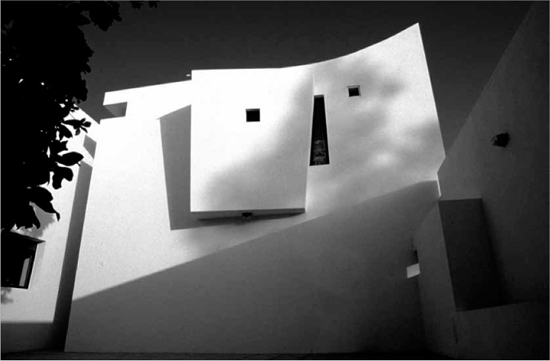

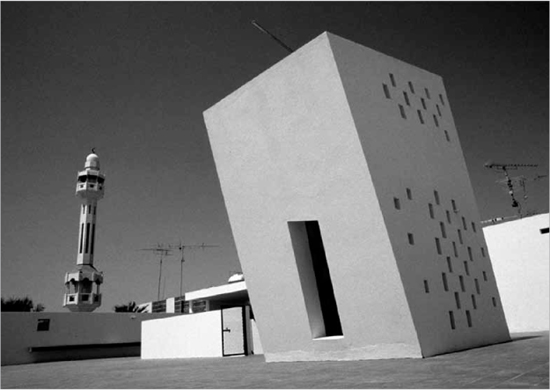

However, probably the most interesting attempt as yet to introduce transformative architectural ideas into the Persian Gulf region comes from an older project, back in the early-1990s, for the Villa Anbar in Dammam, Saudi Arabia.37 It was the first project designed by Peter Barber, now a leading housing designer in the UK. Barber lived on site and worked with local craftsmen for a year to deliver what is an undeniably beautiful modernist house with many nods to Le Corbusier, Luis Barragan, etc. (see Plate 32). In addition, Barber’s design also expresses the power relations contained within the dwelling, firstly by giving dramatic form to the chauffeur’s apartment in the front courtyard, through a sweeping roof, and secondly by playing on the gender politics inside the house. The client was a leading Saudi female novelist, and hence while the internal planning conforms to the usual separation of male and female spaces, the twist is that there is a small slot with a sliding shutter that links the two living rooms – with the latch for this shutter placed on the female side so they can look into the male spaces if desired, but not the other way around. Overall it represents an elegant and thoughtful piece of architecture, which was shortlisted for an Aga Khan Award but in the end possibly proved too radical for some tastes.

19.11 Rooftop view to the local mosque

19.12 Interior of maid’s room on the rooftop

Intriguing as these innovative projects are, they are all somewhat expensive examples, rather than truly nimble creative explorations. Instead, what would most help architectural practice for countries along both sides of the Persian Gulf is the spread of small-scale innovative projects which respond to, and thereby capture, the possibilities presented by rapid global change. Here the best exponents are probably the more experimental architectural teachers and researchers working in the Gulf, such as George Katodrytis of the American University of Sharjah. The projects that Katodrytis sets his students require them to unravel and record the hidden daily activities of Dubai, and at the same time look for chances to design according to emerging socio-economic trends in the city. It is an approach based less on formal aspects of design and more on the reading the hidden urban networks and systems in these Gulf cities, seeing the latter as constantly in flux. Rather than being held in sway by the apparent novelties of computer design, or the fixed visual symbols of past Arabic or Iranian architecture, the inspiration comes from everyday lived practices. Intellectual support for this position is given through the argument offered by Teddy Cruz – a Guatemala-born architect who operates in San Diego and Tijuana on either side of the US/Mexican border – when discussing the tasks for architects today:

Architectural practice needs to engage in the re-organization of systems of urban development, challenging political and economic frameworks that are only benefiting homogenous large-scale interventions managed by private mega-block development. I believe the future is small, and this implies the dismantling of the LARGE by pixilating it with the micro: an urbanism of retrofit.38

Teddy Cruz’s projects are themselves deeply ambivalent and fertile in their reading of scale, allowing for the kind of user input to architectural design as hinted at by earlier schemes like Corbusier’s Plan Obus for Algiers, while avoiding the level of state control or physical megastructures that such modernist projects seemed to require. Cruz’s neighbourhood-level projects also chime closely with the complex hybridity created by what Lefebvre described as ‘planetary urbanization’, rather than the outdated notion of treating cities as single distinctive entities. This is not to make the argument that somehow ‘small is beautiful’, but rather to recognise and welcome the sheer intricacy of contemporary urban conditions. A generation ago, Kenneth Frampton wrote of oppositional projects like these as being ‘urban enclaves’ which sought to resist but could never grapple with the increasing domination of consumerist culture, as if their small scale had to be recognised as an inherent problem.39 But now with increasingly relevant theories of the cumulative and disproportionate power of ‘small change’, as proposed by theorists like Nabeel Hamdi, we no longer need to believe in Frampton’s implicitly pejorative reading of the issue of architectural scale.40 Thus we can see that the designs by George Katodrytis through his Sharjah students, and also his practice, StudioNova, try to tap into these everyday flows.41

19.13 Dubai Hub project by StudioNova Architects

19.14 View from within the Dubai Hub

These last examples hint at the kinds of explorations which can be made possible by problematising the concept of scale within globalisation. By avoiding any sense of privilege for large-scale projects, and transferring our attention instead to the social dynamics of scale, the situation contains far more design hope than the deathly monuments of Foster, Gehry and Koolhaas. Smaller projects might not be seen to change the world, and of course always run the risk of being dismissed as marginal: but this ignores the fact that they can be equally as powerful in their design ambitions, and above all, they don’t close down creative possibilities. Network connections such as through the internet are also expanding their influence immensely. We therefore have to stop thinking of globalisation as something vast. Perhaps instead we should try to imagine it as the smallest thing we can possibly conceive of. Globalisation does not have to be about the mega-project, the ostentatious, or the shallowly symbolic. It is certainly not the preserve of profit-hungry multinational corporations, or would-be powerful states, nor is it a vast nebulous entity that is out of control and trying to control us. Rather its essence lies at mutable scales, in the fluid, the unfinished, the fissured and the everyday, as opposed to the generalised. Or to borrow a maxim, globalisation is in the details.

NOTES

1 Marshall Berman, All That is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London/New York: Verso, 1983).

2 Antoine Picon, ‘What has happened to territory?‘, in David Gissen (ed.), Territory: Architecture Beyond Environment – Architectural Design Special Issue, Profile no. 205 (May/June 2010), pp. 94–96.

3 This kind of conceptual error is typified in the comments on Middle Eastern architecture by Cynthia Davidson, which posit architecture as a separate object in relation to ‘global capital’. See: Cynthia C. Davidson (ed.), Legacies for the Future: Contemporary Architecture in Islamic Societies (London: Thames & Hudson/Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 1998), pp. 8–9.

4 ‘Rem Koolhaas: An Obsessive Compulsion towards the Spectacular’, quote taken from interview in Der Spiegel, 18 July 2008, viewable at the Der Spiegel Online International website, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/rem-koolhaas-an-obsessive-compulsion-towards-the-spectacular-a-566655.html (accessed 16 November 2009)]

5 Ibid.

6 Anthony D. King. (ed.), Culture, Globalization and the World-System (London: Macmillan, 1991); Anthony D. King, Spaces of Global Culture: Architecture, Urbanism, Identity (London/New York: Routledge, 2004); Donald McNeill, The Global Architect: Firms, Fame and Urban Form (London/New York: Routledge, 2009); Liane Lefaivre & Alexander Tzonis, Architecture and Regionalism in the Age of Globalization: Peaks and Valleys in the Flat World (London/New York: Routledge, 2012).

7 Robert Adam, The Globalisation of Modern Architecture: The Impact of Politics, Economics and Social Change on Architecture and Urban Design since 1990 (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012).

8 Examples include: Thomas Frank, One Market Under God: Extreme Capitalism, Market Populism, and the End of Economic Democracy (New York: Anchor Books, 2000); Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA/London: The MIT Press, 2000); David Held et al., Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture (Cambridge: Polity, 1999); Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and its Discontents (London: Allen Lane/Penguin, 2002); Joseph Stiglitz, Making Globalization Work (London: Penguin Books 2006); Joseph Stiglitz, Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010).

9 Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford: Blackwell, 1974/91), p. 86.

10 Liane Lefaivre & Alexander Tzonis, Critical Regionalism (Munich/Berlin/London/New York: Prestel, 2003), p. 164: See also the discussion in Lefaivre & Tzonis, Architecture and Regionalism in the Age of Globalization.

11 Mark Crinson, ‘Singapore’s moment: Critical regionalism, its colonial roots and profound aftermath’, The Journal of Architecture, vol. 13, no. 5 (2008): 585–605.

12 Richard Neutra, ‘Regionalism in Architecture’ (1939), in Vincent B. Canazaro, Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity and Tradition (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), pp. 276–279.

13 ‘Top Ten Countries for Manufacturing Production in 2010’, Curious Cat Investing and Economics Blog website, http://investing.curiouscatblog.net/2011/12/27/top-10-countries-for-manufacturing-production-in-2010-china-usa-japan-germany/ (accessed 12 September 2012).

14 This historical argument is made more extensively in Murray Fraser (with Joe Kerr), Architecture and the ‘Special Relationship’: The American Influence on Post-war British Architecture (London/New York: Routledge, 2007), pp. 14–17.

15 Steve Jones, The Language of the Genes (London: Flamingo, 2000).

16 David Edgerton, The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900 (London: Profile Books: London, 2008).

17 Jurgen Habermas, The Divided West (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2006), p. 175.

18 See, for example, the discussions in: Jan N. Pieterse, ‘Globalization as Hybridization?’, in Mike Featherstone et al. (eds), Global Modernities (London/Thousand Oaks, CA/New Delhi: Sage, 1995), pp. 45–68; Jan N. Pieterse, Globalization and Culture (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004). For another interesting study: Sheila L. Croucher, Globalization and Belonging: The Politics of Identity in a Changing World (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004).

19 Stuart Hall, ‘Globalization from Below’, in Richard Ings (ed.), Connecting Flights: New Cultures of the Diaspora (London: Arts Council/British Council, 2003), pp. 6–14.

20 Saskia Sassen, Cities in a World Economy (4th Edition) (Thousand Oaks, CA/London: Pine Forge Press, 2011).

21 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, ‘On the Preconditions of Architectural Work’ (1922), in Fritz Neumeyer (ed.), The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), pp. 299–303.

22 The boldest statement about parametric design as an aspect of cybernetic systems theory is Patrik Schumacher, The Autopoesis of Architecture (2 vols, London: John Wiley, 2010/12): in response, and for an elegant dismantling of the misunderstanding of Deleuzian concepts and systems thinking in the design projects of Hadid and Schumacher, see Douglas Spencer, ‘Replicant Urbanism: The Architecture of Hadid’s Central Building at BMW, Leipzig’, The Journal of Architecture, vol. 15, no. 2 (2010): 181–207.

23 Rudolf Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (London: Academy Press, 1948/98); Robert Tavernor, Smoot’s Ear: The Measure of Humanity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007).

24 Louis I. Kahn, ‘The Room, the Street, and Human Advancement’, his acceptance speech for the 1971 AIA Gold Medal, viewable on the Louisiana Technical University website, http://www2.latech.edu/~wtwillou/A310_410_IDES_Images_sum04/Kahn_1971_AIA_Gold%20Medal.pdf (accessed 19 November 2010).

25 Charles and Ray Eames, ‘Power of Ten’ (1968), viewable on the YouTube website, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0 (accessed 18 January 2011).

26 Rem Koolhaas & Bruce Mau, S,M,L,XL (New York/Rotterdam Monacelli Press/010 Publishers, 1995).

27 Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society – Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture (2nd Edition, Oxford: Blackwell, 2009); Doreen Massey, ‘A Global Sense of Place’, in Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994), pp. 146–157; Doreen Massey, World Cities (Cambridge: Polity, 2007).

28 Office for Metropolitan Architecture, ‘Waterfront City, Dubai, UAE’, viewable on the OMA website, http://oma.eu/projects/2008/waterfront-city (accessed 12 September 2012).

29 ‘Rem Koolhaas: An Obsessive Compulsion towards the Spectacular’, quote taken from interview in Der Spiegel, 18 July 2008, viewable at the Der Spiegel Online International website, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/rem-koolhaas-an-obsessive-compulsion-towards-the-spectacular-a-566655.html (accessed 16 November 2009).

30 Arab Engineering Bureau website, http://www.aeb-qatar.com/ (accessed 15 July 2012): Ibrahim Jaidah, ‘Exploring Urban Identity in the Gulf Region’, paper presented to the Human Habitation: Architecture, Settlement and Cultural Identity in the Persian Gulf Region international conference organised by the University of Westminster’s Department of Architecture, held at the Royal Institute of British Architects, London, 5–6 October 2009.

31 ‘Gulf House Engineering’, viewable on the ArchNet Digital Library website, http://archnet.org/library/parties/one-party.jsp?party_id=12018 (accessed 15 July 2012); Souheil El-Masri, ‘Urban Transformations of Manama and Muharraq’, paper presented to the Human Habitation: Architecture, Settlement and Cultural Identity in the Persian Gulf Region conference.

32 X-Architects website, http://www.x-architects.com/index.php (accessed 28 November 2012).

33 Michael Hensel & Mehran Gharleghi (eds), Iran: Past, Present Future (Architectural Design special issue), vol. 82, no. 3 (May/June 2012).

34 Masdar website, http://www.masdar.ae/en/home/index.aspx (accessed 15 July 2012); ‘Masdar Development’, Foster + Partners website, http://www.fosterandpartners.com/Projects/1515/Default.aspx (accessed 15 July 2012).

35 ‘Qatar Pilot Plant’, Sahara Forest Project website, http://http://saharaforestproject.com/projects/qatar.html (accessed 31 January 2013); ‘Desert Blooms’, RIBA Journal (December 2012/January 2013), p. 14.

36 Peter Oborn (ed.), Al Bahar Towers: The Abu Dhabi Investment Council Headquarters (Chichester, Sussex: Wiley, 2013); ‘Al Bahar Towers’, viewable on the Aedas website, http://www.aedas.com/Al%20Bahar%20Towers (accessed 12 September 2012).

37 ‘Villa Anbar, Saudi’, Peter Barber Architects website, http://www.peterbarberarchitects.com/03_Villa.html (accessed 20 January 2013); Peter Barber, ‘Villa Anbar, Dammam, Saudi Arabia’, in Murray Fraser (ed.), The Oxford Review of Architecture – No1: Culture and Technology Issue (Oxford: Oxford Brookes University, 1996), pp. 10–19.

38 Teddy Cruz, ‘Mapping Non-Conformity: Post-Bubble Urban Strategies’ (2009), Hemispherica website, viewable at: http://hemisphericinstitute.org/hemi/en/e-misferica-71/cruz (accessed 21 March 2011).

39 Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History (London: Thames & Hudson, 1980), p. 297.

40 Nabeel Hamdi, Small Change: The Art of Practice and the Limits of Planning in Cities (London: Earthscan, 2004); Nabeel Hamdi, The Placemaker’s Guide to Building Community (London: Routledge, 2010).

41 George Katodrytis/StudioNova Architects website, http://katodrytis.com/main/ (accessed 21 June 2012).