The Schools

The 1950s Hertfordshire schools and those designed by the A&BB in the 1950s and 60s came to constitute a canon for educationalists and designers in the English regions during these years. These were mainly schools for younger children but there were also secondary schools amongst the better-known and most celebrated. Certain schools attracted a great deal of national and international attention. Study tours were conducted, publications, films, exhibitions and articles were produced in several different languages indicating international as well as national interest. These schools demonstrated elegance in construction reflecting the best in engineering and use of new materials, utility and sobriety in cost-planning, and respect for the visual arts through integrating work by some of the best artists in the country at the time. Educational achievement was also viewed as important but was not the most vital immediate consideration as that was expected inevitably to follow in time with the school in action. That they were visually pleasing, welcoming, warm and vibrant places, supporting a complex variety of different learning situations would, it was believed, eventually ensure a raising of standards. But more than this, the schools would encourage development of character and self belief to the extent that children would confidently and securely move from the primary to secondary school and beyond.

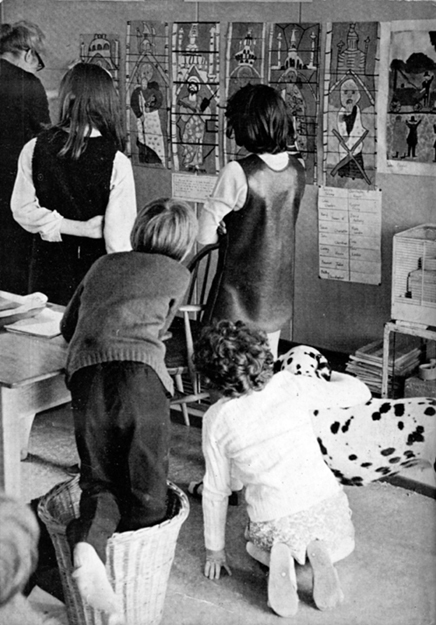

While the earlier Hertfordshire schools were not notably advanced in their educational practice, by the mid 1960s there was clear evidence, in primary schools designed under the influence of the Development Group of a move towards realizing progressive practices through the material environment. In this sense, education and architecture grew more inter-related; architects were increasingly knowledgable and expert in education while some teachers were becoming spacious in their reflection on their practice. We shall see that this confidence was strengthened by a Trans-Atlantic and European consensus among progressive educators and architects as to how schools of the future, especially for the younger child, should look and feel. For older children, a parallel approach envisaged a place that at its heart embodied a vision of learning through engagement of body, hands and mind.

This period witnessed a massive growth in media and communications in traditional and new popular forms. In England, the architectural press regularly featured articles on schools and nurseries stressing their domesticity, comfort and progressive pedagogies. Publication of the Plowden Report on primary education in 1967 spurred further interest in the subject and in 1972 BBC TV produced a series of documentary films about seven schools entitled ‘The Expanding Classroom’.1 At Eveline Lowe primary school in Southwark, London, the programme opened with a view inside the ‘kiva’ room where children relaxed on high bunks, and potted plants surrounded the presenter who remarked, ‘while this might look like a home, it is in fact a school’.2

By the time of Mary’s retirement in the early 1970s, school, at least for the young, was becoming a more comfortable and certainly a more open environment. This placed new demands on a teaching profession that was in the main poorly equipped to teach inside anything other than a box-like classroom. However, in pockets around the country, particularly in Oxfordshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire as well as in London, were teachers committed to new ways of realizing their vocation. They were supported by a network of Chief Education Officers, local advisers and HMI who understood the need for teachers to become more spacious in their thinking.

Not only did these schools attract attention from UK media, but they were of international interest too. In the mid-1960s, a team of educators and film makers from Norway, led by Torvald Slettebø spent six weeks in various Oxfordshire schools, including Finmere, to record and study how they operated, paying attention to how the building supported teaching and learning. The results were published in a booklet entitled ‘Åpne Skoler’ (Open Schools). Slettebø also made a documentary about schools in the West Riding of Yorkshire which was broadcast on Norwegian television as well as 20 films for national TV marketing Oxfordshire ideas. These had a profound effect on the design of Norwegian schools at the time.3

Development project schools were the outcome of meticulous educational planning. While standardized prefabricated parts were used in some early examples, no school was the same, and nothing was repeated exactly. Rather, knowledge was gained in the process of design and construction on each commission that helped to shape the next project. Mary and David usually worked together on each building from the planning stages through to publication of a Building Bulletin outlining in full detail knowledge gained from the process. Their approach also pervaded the general work of A&BB between 1949 and 1972. The development projects themselves only constituted a small part of their total activity; they spent a greater proportion of time on design studies and investigations. A full list of schools completed during these years is given below, where schools on which the Medds worked directly are indicated.4

5.1 Front cover of booklet ‘Åpne Skoler’. IOE Archives, ME/G/19/1

5.2 Back cover of booklet ‘Åpne Skoler’. IOE Archives, ME/G/19/1

ST CRISPIN’S SECONDARY MODERN SCHOOL, WOKINGHAM, BERKSHIRE; MINISTRY OF EDUCATION DEVELOPMENT GROUP (JOB ARCHITECTS DAVID MEDD, MARY CROWLEY, MICHAEL VENTRIS) BUILT 1951–1953. HILLS SYSTEM. LISTED 1993. EXTENSIONS ADDED WHEN THE SCHOOL BECAME A COMPREHENSIVE, 19765

The first school designed and built by the Ministry of Education as a forerunner to promote ideas about secondary modern education and to test the cost limits for school building imposed in 1950, St Crispin’s was designed to accommodate 600 boys and girls, and so was far larger than the primary schools A&B Branch had produced hitherto. It contained a multi-storey ‘tower’ that boldly announced the school within a 49 acre site. The technical aspects of the design, completed by David Medd, adapted the Hills standardized system, now based on a smaller 3 foot 4 inch grid. One of the technical goals of this school was to ‘take prefabrication upstairs’, in Stirrat Johnson-Marshall’s phrase.

Mary together with HMI Leonard Gibbon, worked out the accommodation needs and David remembered it as ‘an anxious moment for us, because it was the first school to demonstrate the new cost limit regime’.6 Andrew Saint has remarked on the challenge of designing this new type of secondary school and how it proved more difficult than designing for primary education. He also claims that St Crispin’s at Wokingham probably had more influence in its educational planning than any other British school built since the Second World War.7 It was certainly noticed outside the UK and was included in Alfred Roth’s selection of the most significant schools for his 1957 edition of The New School. Its impact was due to a combination of factors not least of which was the relative informality of its architecture and the suggestion, through the spaces and facilities provided, of a more integrated approach to education in academic and vocational subjects. The extensive gardens reflected not only a recognition that many pupils would leave school for careers in horticulture but also John Newsom’s particular emphasis on strengthening links between gardening and the natural sciences.8

According to Roth, the most distinguishing feature of St Crispin’s was its successful combining of classrooms in one four-storey building with the loose grouping of special purpose or common rooms in single storey blocks surrounding it. ‘This principle of concentration and decentralization in one and the same layout gives, in spite of its size, a happy impression of variety and intimacy.’9 He also noted the feature of a common area provided for every three classroom groups to support project and group work, as well as the provision of somewhat larger (616 square foot) classrooms intended for more informal teaching and learning. General teaching rooms arranged in a classroom block had adjoining workrooms with sinks and benches.10 Here we see Mary’s ingredients of planning and a belief in the application of planning principles developed in primary and infant schools adapted in an appropriate fashion for the older child.

It did however prove more difficult to break the mould in secondary school typology and to realize a radically different form of school to stand in equal parity of esteem alongside the grammar school.11 At St Crispin’s the plan became in David’s words ‘a straightforward expression of the school curriculum’.12 However, there was more scope for experimentation in such a school especially if led by a sympathetic personality and the first head teacher to serve at the school was noted for his more informal approach to discipline.13 Mary and David had time to investigate the subject with Michael Ventris (1922–1956)14 as a team member and David remarked ‘In these projects, one of many such, we never expected to produce a better school, but one which would display some principles we upheld, some fruits of our investigation, some ideas which may be beneficial and even some to avoid.’15

5.3 Plan of St Crispin’s Secondary Modern School, Wokingham. Development Group, A&BB, MofEd in collaboration with Berkshire County Council. IOE Archives, ME/V/2/7

St Crispin’s did contain elements of a radical reappraisal of a school for children less academic than their peers selected by examination for grammar school. However, at secondary level a deeply entrenched separation of curriculum subjects taught in their own classroom spaces operated, and as the school population grew, the common areas attached to classrooms and intended for group work soon came to be taken over as general classrooms. At some point in its history, walls were erected to produce more classrooms from common and general work areas. A further consequence of that was the cramping of circulation areas, something the Medds had carefully tried to avoid; the original plan virtually eliminated corridors – the dining area and small hall doubling as circulation space in the same way that would be achieved at Woodside Primary (below) some years later.

5.4 A&BB at St Crispin’s school with MBC tucked behind group with L. Gibbon. IOE Archives, ME/E/1/2

St Crispin’s was a statement of Modernism and the design of its buildings declared that the most innovative environments were required as a means of coming to know what a secondary modern school might be. One of the several unusual features of St Crispin’s was a 36 foot high ‘skylon’ equipped with meteorological instruments, a scaled down model of the 300 foot structure erected on the South Bank as a showpiece for the 1951 Festival of Britain.16 This was built in the handicraft workshops by an inspired teacher and pupils a short time after the school opened,17 and stood as a visual symbol of St Crispin’s as a modern school fit for the technological challenges of the future.

The school building was remarkable in other ways and featured ceiling decorations and murals representing the seasons designed by Fred Millett.18 There was also a mural by Oliver Cox installed along the outer long wall of the dining room. While these aesthetic features were admired at the official opening of the school, a boy leaning out of a window was reported as shouting ’If it had been built in marble it would still be a bloody school.’ The school attracted national and international attention as ‘An Experiment in School Architecture’.19 As the local press reported on its opening, ‘the building differs radically from the usual conventional planning for the entire design has been based on educational needs and not on a preconceived plan pattern’.20 The architects John Stillman and John Eastwick-Field wrote a series of articles about the technical development of the school for The Architects’ Journal published in 1952 and 1953.21

5.5 Pupils and teacher erecting a ‘skylon’ at St Crispin’s School. The tower was equipped with meteorological measuring devices. IOE Archives, ABB/A/3/7

5.6 Mural ‘Modular Girl’ by Fred Millett and Oliver Cox, St Crispin’s School. IOE Archives, ME/E/1/2

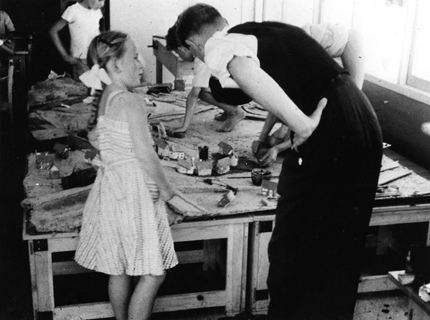

There was much that was technically new about St Crispin’s but more important in situating Mary and her influence was its design around a set of distinctive educational ideas. These were not entirely her own but arrived at in collaboration with HMI Leonard Gibbon, a respected special adviser for secondary education deriving ideas quite probably from conversations with pioneering secondary heads such as Alex Bloom. In a similar fashion to the new thinking on primary schools, the secondary modern was declared to have grown ‘out of the problem itself – the educational needs and activities of its parts’.22 While there were no preconceptions to the design, Mary would have had in mind the Cambridgeshire Village Colleges conceived under the direction of Henry Morris, and certainly the mural art by Fred Millet and Oliver Cox were of a quality that Morris would have approved. The provision for informal drama and musical activities achieved through a split level ‘small hall’ underlines the centrality of arts in the curriculum as envisaged. The ideal that children would learn through first hand experience and practical activities as well as through traditional methods was an important aspect of the education to be developed in such schools.

Such an arrangement corresponds to the Crow Island elementary school already well known and celebrated among the architectural profession, and provides evidence that for the Medds, principles of planning for the younger child were applicable and adaptable in secondary schools.

WOODSIDE JUNIOR SCHOOL, AMERSHAM, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE; MINISTRY OF EDUCATION DEVELOPMENT GROUP (JOB ARCHITECTS J. S. B. COATMAN, MARY CROWLEY, DAVID MEDD, CLIVE WOOSTER) BUILT 1956–1957. LISTED 199323

5.7 Mary with colleagues on site at Amersham, 1956. IOE Archives, ME/D/22

I remember well at Woodside school, Amersham we decided to have a pond and a shelter in the courtyard come what may, which was put in at the start, not something to be cut out at the end.24

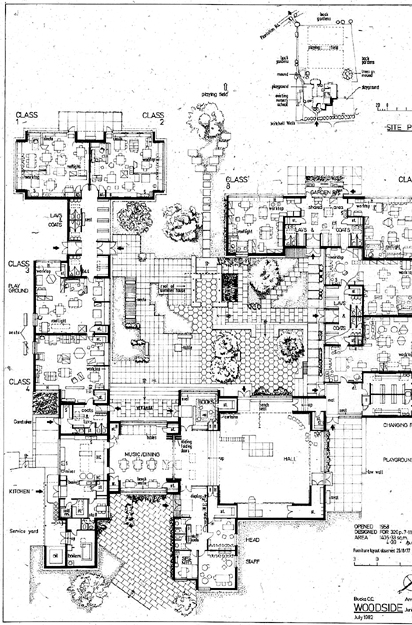

This was the first non-prefabricated construction by the Architects and Building Branch of the Ministry of Education and involved a large team consisting of ten architects and assistant architects, seven quantity surveyors and assistants and a senior member of HMI. However, the Medd stamp is visible throughout. With characteristic respect for scale, comfort and well-being, the Medds considered that the junior school child was relatively deprived ‘commanding no more area than a 5–6 year old yet with pupils who are larger and covering a wider curriculum’. Woodside was the research response. Designed in cooperation with Buckinghamshire LEA, it was a two form entry (eight class) junior school. Research underpinning its design was rooted in careful measurements of children’s physiological characteristics and the Building Bulletin published as the school opened its doors contained detailed information on average elbow heights from the floor of children of junior school age. From this the heights of door handles, drinking fountains, standing work surfaces, wall-benching, heater cabinets, moving lockable units and storage units – the tops of which were intended as working surfaces – were arrived at. The range of eye levels of children, seated and standing, was calculated to inform heights of mirrors and window transoms so that the view out to the nearby landscape would not be interrupted. Various body measurements and analyses of children’s posture formed the basis of design for tables and chairs.25

5.8 Plan of Woodside Primary School at Amersham. Development Group, A&BB, MofEd in collaboration with Buckinghamshire County Council. IOE Archives, ME/V/2/7

Each classroom was planned to be different in character and grouped in four pairs, one for each year, with ample space; 4.39 square foot per pupil for a total of 320 pupils. Each of the eight classroom spaces were designed as a separate entity with a character of their own and arranged in two groups of four to facilitate cooperation between classes and to avoid the need for corridors. Constructed in brick and designed to incorporate some of the rationalization already realized in system building, each pair of classrooms for the four year groups was designed to reflect the developing curriculum.26 Each pair of classrooms shared use of a linked practical space or bay where children might carry out large-scale work such as modeling or construction as supported in a similar fashion at Crow Island School in Winnetka.27 The hall, square rather than oblong, provided a link between the two sets of classrooms. The outside environment was planned with as much care as the inside. The interior court provided a focal point and was planted to significantly increase and enhance educational possibilities, a space that was ‘always full of activity’. A series of small linked courtyards formed by the arrangement of the buildings created what David Medd called ‘the heart of the school’. These courtyards were planned with the idea that they would serve the whole curriculum, becoming the school’s shared focus. ‘The courtyard was as much the teaching area as the non-teaching area so to speak.’28

5.9 The courtyard at Woodside School, Amersham. IOE Archives, ME/E/4/9

5.10 Children building a model town in the general work area attached to their classroom at Woodside School, Amersham. IOE Archives, ME/E/4/10

5.11 Light fitting designed by David Medd. IOE Archives, ME/E/4/12

Woodside was a light and bright school, ample fenestration creating an open atmosphere. Lighting was considered not only in terms of engineering but also through careful attention to the likely educational arrangements to be experienced in any location. The Medds were confident that ‘most of the work would go on in small groups in all parts of the room, and not always in straight lines facing one direction, (this) emphasized the importance of good lighting everywhere, in whatever direction a child might face’.29 To support the research, scaled models were made of each of the workrooms to test the effects of both lighting and colour. Artificial lighting was used but with careful avoidance of the institutional effect this can often bring by means of using seven different styles of light fitting. It was felt that local lighting in the bays of workrooms above wall-benching, would provide a welcome change of character. Lampshades designed for this purpose included cylindrical ’tins’ perforated top and bottom, made from polished and lacquered copper, closely resembling those that Mary and David had observed and sketched in Finland while visiting Aalto’s Finnish Engineers’ Club in Helsinki.30

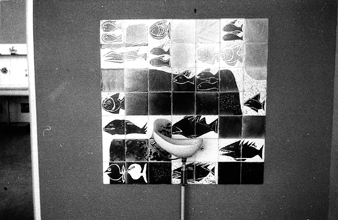

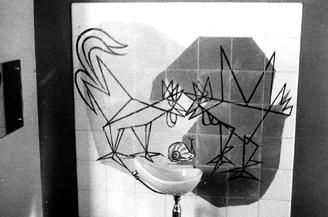

Due to careful gathering of anthropometric data, Woodside saw major advances in furniture design where all items were designed by David, contributing to newly published British Standards Institution specifications for furniture. As in many of the schools designed at the time, the Medds were able to enhance the unique character of spaces by integrating original art work into the building. In this case, ceramicist Dorothy Annan produced decorative tiles for the splash backs of drinking fountains and sinks designed by Adamsez to David Medd’s specifications (Figs 5.12, 5.13 and 5.14). In this way it was intended that ‘the craftsman’s contribution should be associated with the things one uses, ubiquitous and not confined to one selected spot’.31 Annan produced a mixture of animal designs including a sketch of cockerel and snails with a dark blue line on a yellow background that one reviewer thought ‘extremely lively’.32

HMI Robin Tanner made a formal inspection of the school at its opening and was delighted with the building. ‘There were no surprises anywhere. Coming into the building was rather like coming home’. He had expected to see fine attention to detail and was not disappointed.

I found myself drawing door and window fastenings, the display units etc – nothing has been left to chance. The use of hanging textiles (and the lovely choice of these) gives what most new schools lack, namely an inhabited and cared for appearance. Texture everywhere is as important as colour … the link too with the outside world (in colour) is extremely satisfying (and) the scale of everything seems absolutely so right for children.33

5.12 Sinks with splash back tiles by Dorothy Annan. IOE Archives, ME/E/4/9

5.13 Water fountain with decorative tiles (fish motif) by Dorothy Annan. IOE Archives, ME/E/4/12

5.14 Water fountain with decorative tiles (cockerel and snail) by Dorothy Annan. IOE Archives, ME/E/4/12

On the other hand, Tanner was already disappointed with the newly appointed head teacher and ten class teachers, finding only one of them suitably appreciative of the potential offered by the building.34 The head teacher lined pupils’ desks in rows and chose a traditional approach not entirely in sympathy with what the design offered or permitted. Tanner was also scathing about the head teacher’s wife who, filling a gap as a temporary teacher, had ‘introduced pitifully vulgar and ugly cut-out friezes into the (class) room, which I hope the Medds will never have to see!’

For decades, the teaching staff at the school effectively resisted the building and the Medds were disappointed to the extent that they did not return for many years. However, for a short time during the late 1960s the school began to operate in ways more akin to the progressive philosophy and practice that the Medds had intended. This was under the headship of Gordon Morris, 1967–1971.35 At this time Christian Schiller visited the school during the 1970s on a number of occasions, the last time with Mary in July 1977 shortly after its conversion by the Medds into a middle school.36 Student teachers attending Schiller’s London University of Education teacher training course were taken to Woodside regularly which he declared was his favourite primary school. But the conjoining of architecture and education at Woodside was short-lived. In 1982, on visiting, David Medd noted the fall in the numbers of children attending and was disappointed to see that while no accommodation was closed off, ‘the extensions’ meaning the workspaces ‘are little more than a repository for furniture’.37 The story of Woodside underlines the importance of teachers understanding and being in sympathy with the intentions of the designers and it is through habitation that the possibilities are realized or rejected.

FINMERE VILLAGE SCHOOL, OXFORDSHIRE; MINISTRY OF EDUCATION DEVELOPMENT GROUP (JOB ARCHITECTS DAVID AND MARY MEDD WITH PAT TINDALE, BUILT 1958–1959. ENLARGED 1973, LISTED 1993)38

Initially, the Ministry of Education had invited Mary and David to speak on the subject of ‘the village school’ at an event in Buckinghamshire and to write a Building Bulletin with this as a focus. They admitted their lack of knowledge about the subject and suggested that they might learn through building, so Finmere School, Oxfordshire alongside Great Ponton, Leicestershire, together afforded possibilities of researching village schools in general through actual design and construction. While Mary and David designed Finmere, the architect Pat Tindale took responsibility for overseeing construction since Mary and David were in the USA for the whole year during this period.39

5.15 Plan of Finmere School. IOE Archives, ME/Z/5/2/150

In Oxfordshire, under the guidance of Chief Education Officer A. R. Chorlton, HMI Robin Tanner40 and primary adviser Edith Moorhouse, there had developed an interest in the potential cooperation and collaboration between schools and teachers across the expanses of rural land that divided one school from another.41 Visits were exchanged and these were seen as vital for invigorating primary education by local HMI. Such was the case in Oxfordshire where, as Robin Tanner recalled ‘ideas spread as teachers made experiments in creating a new kind of learning environment within old buildings’.42 Edith Moorhouse was convinced that the needs of teachers and pupils were changing and devoted her career to ensuring that teachers in Oxfordshire were trained to be spacious in their thinking and progressive in their practice. She was aided in this by HMI Eric Pearson.43 There was also, in Oxfordshire, a commitment to challenging the traditional character of schools through the medium of in-service training. Moorhouse had attended Christian Schiller’s summer school courses, met the Medds and recognized the opportunities for transformation offered by school building renewal. She carried through a belief held in common with the Medds that only the best was good enough for children and that they should be surrounded by decent modern buildings, honest crafts and good art. Likewise, painting and crafts were regarded as a means to growth and intellectual development rather than an activity to supplement the core curriculum.44 To support this, Tanner advocated the development of a ‘workmanlike internal classroom environment of quality with a great deal of thought about the objects and tools to be placed within the primary classroom’.45

Moorhouse was described by the Medds as ‘one of the few “space persons” in education who have the ability to see educational ideas in terms of the arrangement of space needed for the activity’.46 A great sense of trust and mutual understanding developed between the personalities involved in Oxfordshire who all became close friends of the Mary and David. In her role as primary adviser, Moorhouse had recruited George Baines from a headship in Buckinghamshire to lead in a newly-designed school in the small Oxfordshire village of Eynsham. Baines had attended courses organized by Schiller and Tanner and was known to the Medds as one of the primary teachers able to understand the environmental needs of young children. Through his innovations with furniture, materials and space in the primary school in his first headship at Brize Norton and later at Eynsham Baines became known nationally as a key advocate of child-centred education.47

5.16 Finmere School, outside. DLM personal collection

Finmere was considered the first opportunity to put ‘new life’ into a deprived type of school. The range of work for about 50 pupils from 5–11 years and 2 teachers, demanded a new look at the normal pattern of 2 classrooms.

The school was divided into three spaces which, when required, could be opened up to be used as one by means of moveable walls. The spaces were planned down to the smallest detail including the furniture layout.48 The two central spaces were further subdivided into a library, sitting room (for children) including a ‘fire place’ and a bed, cooking area and general practical area or ‘bays’ for construction work. There might have been an open fireplace, as was the case at Crow Island, but in adapting the idea to a smaller building there was instead an electric radiator to sit around. The bed was set in a small alcove, curtained off. All of the spaces had easy access to a shared verandah and open playing field with a specially constructed mound for play. According to Schiller, for the first time ever Oxfordshire children and their teachers were released completely from the confines of walled boxes and given a planned environment of opportunities.49

Finmere, like all of the Medd schools, was research in practice and its development according to David, ‘made us analyze the ingredients of primary education which helped us in our next school in Southwark’.50 From this time on, we see the set of five ingredients being referred to for development projects directed by the Department and also reflected in schools designed by local authorities influenced by the Medd approach, such as Eynsham Primary School in Oxfordshire.

Eynsham came to be known as one of the most advanced primary schools in Britain. It received an average of 30 visitors a week shortly after its opening in 1967, some from as far afield as the USA. While the building was designed by Oxfordshire County Council architects it certainly was influenced by a common philosophy shared by the head teacher, George Baines, Christian Schiller and the Medds. Mary Crowley’s ingredients were certainly an integral part of the design. At Eynsham, each child had its ‘home bay’ where it started and ended the day with its home teacher within a family group of mixed aged children. The bays doubled up as interest areas; one for sand, woodwork and construction, one for role play, others for mathematics, cooking or quiet reading.51 The Medds maintained a strong friendship with George and Judith Baines for the rest of their lives and their mutual respect was the foundation for reinforcing a relationship between progressive or child-centred teaching and learning on the one hand, and school architecture on the other. From Baines’ experiments and improvisations with furniture and space at Brize Norton Primary School the Medds had realized the planning of Finmere school and from that experience went on to develop their ideas in a more challenging inner city environment.52

EVELINE LOWE NURSERY AND PRIMARY SCHOOL, MARLBOROUGH GROVE, LONDON BOROUGH OF SOUTHWARK; DES DEVELOPMENT GROUP (JOB ARCHITECTS DAVID MEDD, MARY CROWLEY, JOHN KAY, NORMAN REUTER) WITH LCC (ILEA AFTER 1965), DESIGNED 1963–1964, BUILT 1965–1966. LISTED AT GRADE II IN 2006. EXTENDED 2011)53

Eveline Lowe had been designed at the time when the influential Plowden Report was being prepared and its features anticipated recommendations to be made by the Central Advisory Council under Bridget Plowden reviewing primary education in England.54 The original school, Rolls Road, had been destroyed by bombing in the Second World War. The name of the new school was significant. Eveline Mary Lowe had been an elementary school teacher who entered local politics in London, elected to the London County Council to serve as a Progressive Party councillor in 1922 and as a Labour Party councillor in 1925.55 In 1939 she became the first female leader of London County Council. The school is in Southwark where Eveline Lowe had lived and in the ward she represented.56 As such it was sited in a densely populated part of London, just off the Old Kent Road. But the Medds believed it was possible and important for children’s well-being to bring the best features of a village school into this tight urban context. As David Medd explained, ‘the design breaks down what might have been an institutional block into something like a small village that he (the child) can wander around without being aware of the whole’.

Eveline Lowe, unnamed and known as ‘Rolls Road’ during its design, was under construction in 1965, supervised by Norman Reuter. Guy Hawkins, an architect working alongside David and Mary at the A&BB Development Group was put on the team to detail and develop the external works for the nursery unit. To prepare for this, as was now routine, Hawkins visited several primary and nursery schools in South London, ‘selected for the quality and forward-looking character of their work or for the interest of their organization and methods’57 where he talked with teachers to get ideas. Hawkins designed low walls, planting beds, and a splash pool, broadly in accordance with the Medds’ original plans. David Medd was at the time much occupied with designing a full range of furniture for the school, both loose and fixed, and the selection and detailing of worktops, sinks, shelving, pin boards, chalkboards and curtains, as well as the lighting and colour schemes with great attention to the detail of these matters.58

At Eveline Lowe the Medds refined their planning ‘ingredients’ of designing schools for younger children. By this time they believed that as long as these ingredients were present, one could be confident that education would flourish in the hands of ‘good’ teachers while the emphasis on each would vary within the total area available.59

As well as producing a Building Bulletin about the evolution of the school design, the Medds expanded on how their planning ingredients were essential elements in the required ‘built in variety’ in an article they co-authored for The Froebel Society Journal in 1971, The ‘home base’ should not be merely a material space but a place where children would meet and talk together with their teacher in an atmosphere of mutual trust ‘amongst things that belong to them and are made by them, making it feel their own. This is a comfortable, soft friendly place to be in with curtains, pictures, flowers, a carpet, window seat, possibly a bed to rest on.’60

5.17 Ingredients of planning. IOE Archives, ME/M/10/2

5.18 Ingredients of planning, outside. IOE Archives, ME/M/10/3

Therefore the home base was the antithesis of the traditional classroom, the notion being that a child could only thrive and learn well in an environment that supported strong healthy relationships with peers and teachers. A key point was that it would be neither large enough nor furnished for everyone to sit at tables and chairs. In these ways it would be made difficult to teach in traditional ways and the hegemony of the formal classroom was challenged.

The planning of enclosed rooms was developed at Eveline Lowe and there were several different quiet areas built in. These enclosed spaces might be used for quiet activities such as reading or story telling or for making a noise such as music but it was envisaged that no more than ten children at a time might gather there with or without their teachers. In planning, each group of 30 pupils was to have its own withdrawal space connected loosely to its classroom area- ‘group C’ had its ‘bedroom’ and ‘group B’ its ‘kiva’ while yet another group was provided with an uninterrupted space but with plenty of furniture and fittings to help subdivide when required. A photograph published in the Building Bulletin shows a group with its slightly raised carpeted area suggesting quiet reading beyond another group of children working around a table, some sitting, some standing. In the same image, there is a glimpse into the ‘Quiet Room’ between two other rooms, presenting a view reminiscent of the paintings of interiors by the Dutch seventeenth-century artist, Pieter de Hooch, a favourite of Mary’s.61 ‘Built in variety’ was an educational aspirations of this approach to planning, amplifying in the design of new schools what seemed to be required through observing teachers working in less than adequate conditions. Such variety was aural as well as physical and Eveline Lowe was an experiment in built in variety of soundscape.

One of the seven different ‘quiet areas’, the ‘kiva room’, attracted particular attention and was one of the many ideas that Mary and David had acquired during their year of travel in the United States. The ‘kiva’ (a private meeting place for Pueblo Indian communities) was furnished simply with a round table and a rocking chair and its furnishing with carpet and wooden bunks created a close acoustic (Fig. 5.19). This was a cosy space of approximately 12 feet by 12 feet with two steps forming perimeter seating around three sides and two small windows with light curtains. Some of the walls were timber-clad and some were covered with domestic patterned wallpaper complemented by the bamboo light-shade which David Medd had designed and had especially manufactured for the school in Bangkok. Off one side were four bunks and on another wall, shelves for books. This was designed to be a place where, ‘children can get away from the clutter and paraphernalia of their other work and sit around on their haunches and listen to or talk with their teacher, all forty of them or in ones and twos.’

The general work areas were where larger groups of children might gather and these were conceived as relatively uncommitted spaces where temporary groupings might come and go and ‘structured situations be contrived by means of trolleys, screens, worktops and tables’. The various bays might be more specifically set up to indicate the kinds of activities that could occur there, including ‘wet and messy, where water, clay, earth, plants, insects, fish, animals can be dealt with’.62 The final ingredient was provision for regular use of the outdoors through careful consideration given to landscape and to covered areas (verandahs) immediately outside the buildings. The Medds indicated in their writing together how the outside should be more broadly defined.63 Given the kind of teachers who understood the emerging potential of the school and its situation,

work can overflow from the building into covered areas and garden courts; into the surrounding landscape of farms and suburbs, streets or docks. And whatever the site, there is always something to exploit and make the best of … (grass, a stream, local materials, rough ground, excavated earth, walls of a disused shed – these could all become starting points for work and play).64

And given architects who sufficiently understood education and its changing requirements, it would be possible to ‘resist the pressures of the engineers of interior space who would have our buildings offer all protection and no connection’.65

‘Out goes the classroom and in comes the Kiva’ – Daily Mail comment on Eveline Lowe.66

Spaces were designed to offer and suggest a variety of possible uses and throughout the school the materials chosen were designed to counter any institutional character replacing it with an impression of domesticity. This was expressed by the Medds as the ‘inherent quality’ they were striving for in an architecture that would stimulate the senses and enliven the experience of overall warmth together with ‘the coolness or clarity of lighting; the woodiness of wood, the whiteness of white, the softness of a carpet, the smooth matt surface of a clean table’.67

Such de-institutionalization implied a shift from teacher-directed learning to self-directed learning. This was believed to be the dominant trend and a sign of a modern and high quality education. With this in mind, a long corridor area was clad in timber and divided into bays which might be used for study and group learning during parts of the day and could be adapted for dining in family groups at lunch times: a combination of circulation, dining and exhibition space. In other words, such a space was never envisaged to be a corridor but was to be useful throughout the school day, performing a number of functions.68 On the other hand, a negative unpredicted outcome of this layout in practice was that children in the bases nearer the hall were regularly disturbed by children from more distant bases passing through on their way to PE or music, as there were no separate corridors.

The emphasis on the senses, so evident in the careful interior decoration and use of materials and colours was as important to the Medds as the structural shell and overall plan. This nuanced response to modernism might have been identified as ‘romantic pragmatism’ from an architectural point of view but from an educational perspective, this betrayed an allegiance with the child in an environment that they had no choice but to inhabit every day. It might at least be the sort of place a child felt comfortable to be in.

5.19 The Kiva, Eveline Lowe School. IOE Archives, ABB/A/35/18

5.20 Plan of Eveline Lowe Nursery and Primary School, Southwark. Development Group, A&BB, MofEd in collaboration with the Inner London Education Authority. IOE Archives ME/R/3/36

The layout was linear and straggly, due to the site, but this gave rise to a number of very pleasant and useful outdoor areas, enclosed by the building on two or three sides, some covered with a translucent roof. The school influenced a generation of school architects concerned with primary school planning particularly in London.69 Nora Goddard, an Inner London Educational Authority Inspector was seconded to the secretariat of the Plowden Committee and joined the planning team for the new school. It was conceived of and designed with a complete range of furniture, including rocking chairs made by David Medd’s father.70

The interior and exterior spaces for play, study, teaching and learning fundamentally questioned the traditional arrangements of classroom spaces normally found in a primary school. The planning of the school was conceived of as research in practice and celebrated as such. Soon after its formal opening, the Sunday Telegraph Magazine carried an illustrated article about its features entitled ‘School Without Classes’. It reported that in the grounds there were plans to construct an aviary, an adventure playground and a zoo which a neighbouring secondary school would help to build. In a densely-populated city environment where play space was so scarce this was seen to be vital and the subsequent Building Bulletin published to report on the design of Eveline Lowe envisaged the development of an adventure playground to the east of the site at the point at which an incendiary bomb had destroyed the previous school building during the war.71

5.21 Pupils caring for school pets at Eveline Lowe School, 1960s. IOE Archives, ME/V/2/1

In an era that encouraged experimentation and breaking out of old moulds, it was believed that innovative and inspirational teachers would discover or develop an independence of spirit coupled with an inclination towards team teaching and collaboration. The plan of Eveline Lowe was intended to support such practice demonstrating the most innovative and forward looking pedagogy of its time.

Such a vision of course depended entirely on a teaching staff that understood the building and its potential. Eveline Lowe was initially led by head teacher Betty Aggett, in whom the Medds had great confidence. Aggett had been able to prepare fully for taking over the school by obtaining experience of primary teaching around the country during a sabbatical year, meeting ‘others in her profession whose work had been influential in primary school practice… In this way she made valuable links with schools in other authorities and achieved a keen understanding of the directions and opportunities of her own school.’72 Her deputy was Henry Pluckrose who had a special interest and expertise in art and craft in the primary school.73 The team of educators and architects who worked on the plans were committed to a shared view of education and worked with a ‘common vocabulary of design’.74 In later years, the school was led for many years by Gary Foskett, a teacher who had as a pupil attended schools designed by the Medds and who understood the kind of education these architects had envisaged at Eveline Lowe.

All plans for Eveline Lowe were drawn up with the furniture carefully organized as a test of the adequacy of space standards. This was not intended to be prescriptive as the Medds believed and trusted that furniture layouts would change as teachers and pupils took control of their environment. They were inspired by the approach of Larry Perkins and his team of architects in the USA who used model furniture to encourage teachers to experiment with spaces and equipment. At this time too, the Medds were beginning to be involved in extensive in-service training courses for teachers in which they also used model furniture to encourage discussion.

DELF HILL MIDDLE SCHOOL, LOWMOOR, BRADFORD; DES DEVELOPMENT GROUP (JOB ARCHITECT DAVID AND MARY MEDD, GUY HAWKINS) WITH BRADFORD METROPOLITAN DISTRICT COUNCIL, DESIGNED 1966, BUILT 1968–1969, DEMOLISHED 200175

The focus of the Medds’ work in the 1950s and 60s had been mainly in the provision of buildings for younger children although they had worked on secondary schools at Hertfordshire and at the Ministry of Education. However Mary was particularly interested in the planning implications of the abrupt transition occurring in the English system from primary to secondary school around the age of eleven. One solution explored during her time at the Ministry, for easing children’s experience of transfer was the concept of the middle school. This possibility was much favoured by her as it suggested an extension of primary education principles into the secondary school for older children. Another idea was the ‘lower school’ as a space of distinct character within secondary institutions where a child could move gradually from the generalist classroom towards specialist teaching and facilities.76

By the early months of 1966 the team had started work on Delf Hill Middle School, in Bradford, thought to be ‘one of the best examples of Mary’s approach to planning’.77 Delf Hill was in fact one of the last projects Mary Crowley worked on at the DES before retiring in 1972. One of the ideas mooted in the work leading up to the Plowden Report (1967) Children and Their Primary Schools, was the possibility of varying the traditional age of transfer from primary to secondary school, and having ‘first’ and ‘middle’ schools, which would effectively prolong some of the approaches to teaching practiced in the primary school for one or two more years. Middle schools with age ranges of 9–14 or 9–13 were envisaged, but there was no model yet developed. As such, it was considered appropriate that the A&BB Development Group should investigate. Mary gave a presentation to the Branch on the question of Middle Schools design where she analysed how much space and money an eleven year old pupil would cost in a middle school compared with a secondary school. The result was convincing and illustrated the importance of the middle school in the context of transition from small primary to large secondary.

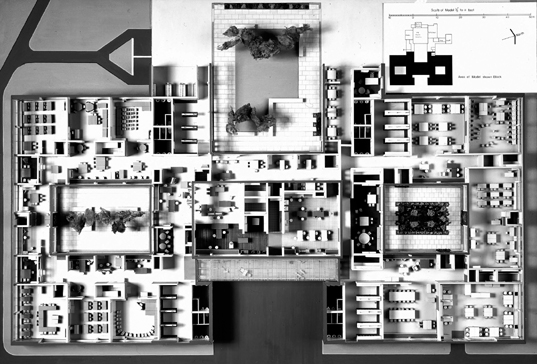

5.22 Model of Delf Hill Middle School, Bradford. Development Group, A&BB, MofEd in collaboration with the City of Bradford. Victoria and Albert Museum, Architecture room.79 RIBA Photographic Collection

There were also pedagogical arguments in favour of the middle school, an organizational structure adopted by many Local Educational Authorities in the late 1960s and 1970s.78 It was more popular in some areas than others and suggested a new type of building might be designed to fit the needs of this age group and the education they were to enjoy. The Medds considered the middle school to be a progressive innovation as did one of its advocates, Alec Clegg, Chief Education Officer for the West Riding of Yorkshire. However, Christian Schiller, Staff Inspector for Primary education and friend of both the Medds and Clegg, was firmly opposed, believing that the middle school would harm the achievements to date of the primary sector. Clegg, while sympathetic, was less convinced than Mary by the educational arguments for extending the character of primary school design in to this age group. The A&BB group initially planned to work with Clegg but differences of approach led them to proceed elsewhere. Bradford LEA provided an opportunity.

Working for Bradford was, of course, a kind of homecoming for Mary. J. S. Nicholson, prospective head of the new school and editor of Education in Bradford 1870–1970 was especially delighted to meet and work with Mary as he was acutely aware of the contribution to the city that her father Ralph had made at the turn of the twentieth century.

5.23 Children playing outdoors Delf Hill Middle School, Bradford. Development Group, A&BB, MofEd in collaboration with the City of Bradford. IOE Archives, ME/V/2/1

The school was built in the SCOLA system of construction (Second Consortium of Local Authorities). As at Finmere, Woodside and Eveline Lowe, the Medds were able to design every aspect of the interior. Careful measurements were made of the children to ensure, for example, that the two tiers of lockers above the coat hanging pegs could be reached by all of the children.80

The working area within the school, with 420 pupils, was divided into four single-storey teaching centres, each for 105 children, and 4 teachers for the basic curriculum. Each of these centres was further divided into areas for collective work and smaller areas for small group or individual work providing for built in variety. From there, pupils would go to more specialized centres for science, languages, PE and drama and music that were situated around a sheltered garden. As David Medd later reflected ‘there were no rows of look alike classrooms’.81 Chalkboards were provided in various colours: dark red, dark blue and dark green (corresponding to British Standards).82 These were intended for the children’s use. In 1975 the school, which boasted ‘superb kitchens and workshops for the use of both sexes’,83 was celebrated as entirely modern in a BBC television programme, ‘Delf Hill Middle School – A New Way of Learning’, which was broadcast about its educational aims.84

A favourable analysis of Delf Hill by a member of staff who evidently understood the architects’ intentions was recorded in the early 1970s by David Medd in his notebook.

I loved it and so did the children and staff. It made us develop cooperative teaching, it prevented us from formalising our relationships with the children and indeed its greatest gift to us was the way in which it united us all staff at all levels, children staff and even all our visitors. We had something like 1500 visitors. In spite of the very young and inexperienced staff, it was possible to manage. In the conventional school building with classes shut away, this would have been asking for disaster.85

5.24 Delf Hill interior looking across one of the bases to a shared work area. IOE Archives, ME/V/2/1

COMPREHENSIVE SCHOOL ADAPTATIONS FROM EXISTING BUILDINGS

While 1967 had seen publication of the Plowden Report on primary education in England, attention was turning to secondary schools given the Labour government’s policy of strongly encouraging LEAs to move from a selective to a comprehensive system.86 A national campaign for comprehensive education had been launched and across the country questions raged about what such a school was and might be.

In 1965, the Labour government’s Circular 10/65 initiated secondary level education reorganization in the regions and the DES eventually had to offer guidance on how to proceed. The idea was that educators should look at buildings and architects look at education in a cooperative effort towards knowledge exchange and construction. By 1967 most of the Development Group, including the Medds, were working on this now urgent challenge. Mary dealt, as usual, with the organizational and numerical questions, and David did some of the design studies. The Group turned to Scandinavia and Sweden in particular to learn more about comprehensive schools and their design. Sweden had embarked on developing a fully comprehensive system after the Second World War and so had good experience to draw from.87 Therefore in November 1967, the Medds and four others – educators and architects – travelled to Sweden for a nine day official visit. The educators were an HMI, as well as deputy education officers from Manchester (Kenneth Laybourne) and Berkshire (John Hornsby), the two authorities with whom the Development Group were working at that time on the design of new comprehensive schools. After they returned they published Design Note Four about what they had learned.

The visit was arranged by the head of the school planning branch at the Swedish National Board of Education. Four regions were studied: Stockholm city, Järfälla, Västerås and Örebro. These were at the time considered to be Sweden’s ‘most progressive and education minded areas’.88

The importance of Sweden in this respect had been underlined in the early 1960s through publication of the results of ‘the Swedish Study’ by Stuart Maclure, an educational commentator and journalist well known to and respected by the Medds. The principal findings of a study conducted by Professor Husén and Dr Nils Svenson had shown that removal of streaming had not harmed the brighter children and benefitted previously low achievers. The Grundskola (comprehensive schools for children 7–16) were found throughout Sweden and the best of these were visited by the team form the UK.

During their formal visit the Medds and the team met educationalists and architects at the Swedish National Board and visited schools built by the Stockholm Board of Education.89 They also met for dinner at the Hotel Reissen on Stockholm’s waterfront, familiar to Mary from her time spent there before the war.90

At Jakobsberg they visited three schools including a ‘vocational’ school, while at Västerås, just outside Stockholm they visited a variety of schools including a nursery and a ’Free-time home‘. In their social time they took in a visit to the new concert hall at Västerås. Typically, they did not confine themselves to looking at schools for older children but whenever there was a chance, took the opportunity to visit kindergarten and nurseries which they found to be exemplary and charming. ‘The domestic atmosphere, the design of related practical areas, resting areas and so on were precisely what English infants’ (5–7 years) teachers were working towards.’

In Örebro, they had discussions with the director of schools and chief architect. They visited schools including a 1–6 grade school at Varbergaskolan, but also made a detour to visit the town library and youth club used by children in their lunch break. There they took lunch themselves and visited the ’Free-time home’ at Oxhagen near Varberg.

The attitudes towards the education of the younger child they encountered in Sweden were to Mary’s and David’s liking, especially commitment to a unified curriculum that avoided prematurely separating ‘academic’, ‘practical’ and ‘aesthetic’ work. The less formal approach to learning-through-doing they encountered in the schools for younger children they thought was leading entirely in the right direction. They noted that the area per pupil allowed in these schools for the younger children was generous, and practically double that for equivalent English schools. Classrooms were well equipped and modern, especially with regard to visual aids, and their lighting and ventilation was excellent.

Their impressions of the relationship between architecture and pedagogy at the Grundskola were less favourable as the rigid formality of classrooms and corridors did not seem to be as educationally adventurous as some of the community centres and youth buildings they visited where they saw ‘excellent accommodation for hobbies, social events, exhibitions, games, discussion groups, amateur drama etc’. Here they could observe Swedes taking the opportunity of integrating school buildings into the planning of other public buildings and facilities in a way that resembled the intention of Cambridgeshire Village Colleges of, the 1920s and 30s. As David noted optimistically, in Sweden, ‘the school is at the heart of things, in a way which surely is going to encourage a new and more cooperative attitude to the school by the community’.91

Henry Morris was never far from their minds when they viewed or were concerned with the development of community schools for older children. A short time after the visit to Sweden, Mary acknowledged the indirect influence of Morris in a letter to Harry Rée.

What Henry Morris did in Cambridgeshire has been a definite influence in our whole general approach … there is not much direct evidence of this influence in most of the projects we’ve been personally concerned with, simply because there weren’t sufficient openings. But both in Oxfordshire and at Eveline Lowe, relationship with the neighbourhood were much discussed. And in the work we did both for ’Half Our Future’ and for ’Plowden’ this was very much in our minds.92

NOTES

1 Central Advisory Council for Education (1967) Children and their Primary Schools (The Plowden Report). London. HMSO.

2 Eileen Molony (1914–1982) was a BBC television producer involved in the production of a wide range of programmes, particularly in the areas of travel, natural history, education and child development. She produced the television series ‘The Expanding Classroom’ which was first broadcast in 1969 and intended to provide an insight into schools which were implementing some of the recommendations of the Plowden Report.

3 An online version of ‘Åpne Skoler’ is available at http://www.agderkultur.no/Oxfordshire-skole/Side1.htm. Accessed: 29 August 2012. The films can be viewed online at www.agderkultr.no.

4 See Appendix 1.

5 See Maclure (1984) p. 140; 200; Saint (1987) pp. 133–5; Building Bulletin, 8. December 1955.

6 DLM notes on the archive, 1946–1972, p. 3.

7 A. Saint (1987) p. 133.

8 D. Parker (2005) John Newsom. A Hertfordshire Educationalist. Hertford. University of Hertfordshire Press. p. 37.

9 A. Roth (1957) p. 211.

10 Seaborne and Lowe (1977) p. 190.

11 The grammar schools were selective and provided an academic education.

12 DLM (2009) p. 25.

13 Eric Bancroft served as head teacher 1953–1971. For the first seven years, pupils were not expected to be entered for academic examinations.

14 Michael George Francis Ventris qualified as an architect from the AA in 1947. Ventris worked on St Crispin’s while cracking the Minian Linear B alphabet in the evenings.

15 DLM (2009) p. 25.

16 DLM (2009) p. 25.

17 The Times Educational Supplement, 21 October 1955.

18 The murals were painted over at a later date but parts were recovered and restored in 2011 and 2012.

19 The Listener, 13 October 1955, p. 591.

20 The Wokingham and Bracknell Times, 29 February 1952. p. 1.

21 The Architects’ Journal, 16 October 1952, pp. 469–75; 4 December 1952, pp. 670–76; 8 January 1953, pp. 41–4.

22 BB, 8, p. 2; Saint (1987) p. 134.

23 BB, 16; M. Seaborne and R. Lowe (1977) The English School its Architecture and Organisation Vol II 1870–1970. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul. pp. 172–3; The Architects’ Journal, 1 August 1957; 13 November 1958; Education, 27 September 1958. pp. 403–10; The Times Educational Supplement, 3 January 1958.

24 DLM (2009) p. 22.

25 BB, 16. p. 15. The statures of two-thirds of the children who were to enter the school were taken as this research was to inform the British Standards Furniture range. Surveys had shown that only 5 per cent of school pupils had desks and chairs which were correctly proportioned to their bodies.

26 C. Burke, A. Clark, D. Cullinan, P. Cunningham, R. Sayers and R. Walker, R. (2010) Principles of Primary School Design. London. Feilden, Clegg and Bradley Studios.

27 See below, pp. 183–9.

28 British Library interview with MBC, Tape 4.

29 BB, 16, p. 44.

30 See below, p. 164.

31 DLM (2009) p. 29. One is reminded of Mary’s deep appreciation of the decorative tiles she saw on her visits to Holland as a young woman with her father in the W.C. of her favourite hotel.

32 The Architects’ Journal, 1 August 1957, p. 192.

33 Robin Tanner Report on Woodside school at Amersham, 21 February 1958. ME/E/4/8. The colour specifications are documented. ME/E/4/5/1/2. See also ‘Colour and Finishes’, June 1957. ME/E/4/52/2. Mary had dealt with the choice of textiles.

34 The one teacher who Tanner thought was ‘the best person in the school’ was a Mr Longworth, who had trained at Bretton Hall College in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Seven of the ten class teachers were men.

35 This was W. G. Morris. I am grateful to Guy Hawkins for this information. The succession of head teachers at until 1982 Woodside were Rickerby, Thrower, Morris, Lovell, Bellchambers, Lewis.

36 In 1975, the school became an 8–12 middle School with 350 pupils in 11 classes, with 2 of these in mobile classrooms.

37 DLM notes on visit to Woodside County Junior School, 14 July 1982. ME/E/4/7.

38 BB, 3, HMSO, 1961; D. Rowntree, The Guardian, 25 May 1960; The Architects’ Journal, 30 June 1960, pp. 1005–6; BOUW [Dutch architectural journal], 133, 19 August 1961, pp. 1016–17; Sunday Telegraph, 21 November 1965; Education and Culture, 4, Spring 1967, pp. 19–22; The Plowden Report (1967) Children and their Primary Schools. HMSO, p. 396.

39 Tindale had worked alongside Mary Crowley and David Medd at Hertfordshire, the first of several AA students engaged in school work to help the overstretched architects in the summer vacation of 1946.

40 Tanner became HMI for Oxfordshire in 1956.

41 Moorhouse was appointed Assistant Education Officer for Oxfordshire in 1946.

42 Eric Pearson, cited in Marsh (1987) p. 55.

43 E. Pearson (1972) Trends in School Design: British Primary Schools Today. London. Macmillan.

44 Marsh (1987) p. 23; p. 25; p. 27.

45 Marsh (1987) p. 345.

46 Ibid. p. 65.

47 See Catherine Burke, Obituary George Baines, The Guardian, 27 October 2009. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2009/oct/27/george-baines-obituary.

48 ME/E/18/5.

49 Christian Schiller ‘Changing needs in the design context’, Built Environment, May 1972. p. 96.

50 DLM (2009)p. 30. BB 36, 47 and A&B papers, 16.

51 Brian MacArthur, ‘School without Classrooms’, The Times, 5 July 1968.

52 R. Tanner (1987) Double Harness. London. Impact Books. pp. 160–61. George Baines married Judith Purlock also a teacher. Their papers are deposited at the Institute of Education Archives. A documentary film ‘Conversations between Architects and Educators in Designing the Post-war School’ was made in 2007 featuring David Medd, George Baines and Judith Baines, deposited at the Institute of Education archives. The film was funded by The British Academy. http://www.education.leeds.ac.uk/modx/research/projects/conversations-between-architects-and-educators-in-designing-the-postwar-school. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

53 See Plowden Committee Report; BB, 36 & 47; Maclure (1984) p. 166, 167; Saint (1987) p. 155, 92, 93; ‘The 3 ½ to 9 Age Groups: A New Approach to Primary School Design’, The Architects’ Journal, 17 February 1965.

54 The Plowden Report (1967).

55 Eveline Mary Lowe (née Farren) (1869–1956). The Progressive Party was a political party based around the Liberal Party.

56 Eveline Lowe also became for a short while vice principal of Homerton College, Cambridge where she had trained to become a teacher.

57 BB, 36, p. 5.

58 We know from Mary’s travel diaries how often when visiting schools and kindergarten abroad she had paused to take careful note of such features as curtains, blinds, colours, pin-boards and light.

59 The five ‘ingredients’: a home base; an enclosed room; a general work area; particular bays; and a veranda or covered area. BB, 47, Eveline Lowe School Appraisal. DES (1972) pp. 20–21.

60 David and Mary Medd (1971) p. 9.

61 BB, 36, 31.

62 David and Mary Medd (1971) p. 9.

63 Colin Ward and Tony Fyson (1973) Streetwork. The Exploding School. London. Routledge.

64 David and Mary Medd (1971) p. 10.

65 Ibid. p. 10.

66 DLM (2009) p. 31.

67 David and Mary Medd (1971) p. 11.

68 DLM (2009) p. 32.

69 See for example, Prior Weston Primary, 1968 in R. Ringshall, M. Miles, and F. Kelsall (1983) The Urban School. Building for Education in London 1870–1980. London. The Architectural Press. p. 77. Also St Paul’s, Bow Common ‘Primary Instruction’. Robert Waterhouse, Design Journal (1972). Available online at VADS online resource for the visual arts: http://vads.ac.uk/diad/article.php?title=280&year=1972&article=d.280.26. Accessed 29 August 2012.

70 DLM letter to author, 30 December 2006.

71 The adventure playground was never built, Sunday Telegraph magazine (date); BB, 36. The neighbouring secondary school pupils did help to construct a boat for the primary school children to play in.

72 BB, 36, p. 3.

73 Pluckrose later was head of the Prior Weston primary school that continues to support many of these interests in its new premises at Whitecross Road, Prior Weston Campus, London.

74 See C. Burke ‘“Inside out”: a collaborative approach to designing schools in England, 1945–1972’, Paedagogica Historica, 45, Issue 3, June 2009, pp. 421–33.

75 Saint (1987) p. 155, 156; Maclure (1984) p. 192, 193. BB, 35.

76 On this subject, Mary was in disagreement with Christian Schiller who was not in favour of middle schools. Alec Clegg had misgivings about them too.

77 DLM letter to author, 21 August 2006.

78 The middle school was supported by the 1964 Education Act.

79 Model 1969 by P. R. Carstairs. Perspex, coloured card, paper and sponge 100 × 750 × 523 mm. Given by the Department of Education and Science RIBA: MOD/EDUC/9. Currently exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

80 David Medd commented that they found a two feet difference between the shortest and the tallest school pupils. DLM (2009) p. 35.

81 DLM (2009) p. 35.

82 BS5252 Framework for Colour Co-ordination for building purposes.

83 Richard Bourne (1993) ’The Gentle Sex‘, Education + Training, 12, no. 3. pp. 86–7.

84 Eileen Molony ‘Model of Delf Hill Middle School’; (film). Institute of Education archives.

85 DLM notebook, 20 December 1971. DC/ME/C/1/16.

86 Anthony Crosland,Circular 10/65 see http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/des/circular10-65.html. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

87 In 1950 Sweden introduced the enhetsskola or general school for 7–16 year olds. In 1958 the enhetsskola became försöksskola, which in 1962 changed name to grundskola.

88 DLM typed notes, Nov/Dec 1967. ME/G/26/2.

89 Satraskolen, Bredangskolen.

90 Notes of the visit to Sweden, 20 November 1967. ME/G/26/2.

91 DLM notes from Sweden (1967) p. 4. ME/G/26/2.

92 MBC letter to Harry Ree, 24 May 1971. Rée was at the time researching a book on the life of Henry Morris. HR 22/175.