THE SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT OF ARCHITECTURAL CRITICISM AND PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

Introduction

This chapter addresses the socio-cultural context of architectural criticism and evaluation studies. It considers understanding the context for the critic, evaluator, project or building, and the society at large as a key factor that influences the outcome of these studies. While this book attempts to demonstrate that the “two currently divergent paradigms of architectural criticism and building performance evaluations can co-exist and even complement each other,” I argue that there is a critical and dynamic context that should be considered when initiating criticisms and evaluation studies, and when attempting to understand their value to the individual, society, and profession.

The political, economic, social, and cultural context of studies influences the instigation and function of these studies in intellectual, professional, and scientific aspects of society. Democratic and autonomous societies value personal opinions and user feedback more than autocratic or authoritarian societies. The value of a qualitative approach is inferior to that of a quantitative approach in less developed societies. Cultural beliefs and attitudes continue to affect how people view criticism and evaluation studies. The following account attempts to highlight significant contextual issues that should be understood in order to improve the impact of criticism and evaluation studies in different socio-cultural realms.

Recent trends

Since the end of the twentieth century, the field of architectural criticism and evaluation has witnessed the advent of a new shift in focus from criticism to evaluation, assessment, and performance. It also witnessed the praise of quantitative methods over qualitative ones. “Announcing the death of criticism is nothing new,” wrote Hélène Jannière (Jannière 2010). This is attributed partially to the pressing requirements of the realm of scientific research and granting agencies that value the measured over the perceived and the quantitative over the phenomenological. This shift is also attributed to the emergence of new types of organizational clientele and decision-makers who prefer to utilize quantitative and statistical evidence during decision-making. As Rendell put it, “very few critics seem willing to reflect upon the purposes and possibilities of architectural criticism, or to consider their choice of subject matter and modes of interpretation and operation” (Rendell 2005).

As sustainability is becoming increasingly a requirement, the increase in applying different sustainability assessment and rating systems poses a new challenge to the field. Most projects are obliged to provide evidence of their sustainability strategies, energy conservation, reduction of carbon footprint, and concerns for world climate change. Yet, there is increasing criticism that “these tools [are] still unable to estimate the actual project outputs of sustainable projects, as sustainable measures and technologies can turn out differently in the use-phase. Also, the influence of project end-users is underestimated and not considered properly in these tools” (Abdalla et al. 2011)”

Criticism failed to provide an alternative to evaluation and assessment studies. As Bürger put it, “We live in an age in which the spirit of critique has become strangely numb” (Bürger 2010). There was a time during the mid-twentieth century when criticism was considered the drive to initiate change and improvement of the profession. This period was followed by a period of increased success in evaluation research. The rise of post-occupancy evaluation (POE) research was followed by a more holistic evaluative research covering all building aspects known as building performance evaluation (BPE). It was a clear shift of focus from the “occupant” to the “building” in an effort to achieve more recognition from the prevailing scientific community.

A chronic problem in the field is the value and benefits of its results, and how are they are utilized by practitioners, decision-makers, and users. As pointed out in the Federal Facilities Council (FCC) report:

only a limited number of large organizations and institutions have active POE programs. Relatively few organizations have lessons from POE programs fully incorporated into their building delivery processes, job descriptions, or reporting arrangements. One reason for this limited use is the nature of POE itself, which identifies both successes and failures. Most organizations do not reward staff or programs for exposing shortcomings.

(Federal Facilities Council 2001)

Among the barriers to making POE more effective, the report added: the difficulty in establishing causal links between positive outcomes and the physical environment; reluctance by organizations and building professionals to participate in a process that may expose problems or failures; fear of soliciting feedback from occupants on the grounds that both seeking and receiving this type of information may obligate an organization to make costly changes to its services or to the building; lack of participation by building users; and failure to distribute information resulting from POEs to decision-makers and other stakeholders (Federal Facilities Council 2001). Knowledge gained from evaluation studies should be fundamental for an informed new buildings and projects decision-making process.

Defining the socio-cultural context

The term “socio-cultural” is an umbrella term that encompasses the social and cultural aspects that exist in a particular context. According to the American Heritage Dictionary, socio-cultural means “of or involving both social and cultural factors” (The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language 2011). It suggests the inseparable nature of culture and society.

Socio-cultural studies traditionally focused on the interface between society and culture and its impact on people and their actions. This approach was “first systematized and applied by L. S. Vygotsky and his collaborators in Russia in the nineteen-twenties and thirties. [It was] based on the concept that human activities take place in cultural contexts, and are mediated by language and other symbol systems” (John-Steiner and Holbrook 1996). While this chapter attempts to demonstrate the impact of socio-cultural context on architectural criticism and evaluation, it does not attempt to lessen the impact of other economic, environmental, or technological factors. And, as Bürger “politely” put it, “the general political climate can probably not be denied” (Bürger 2010).

According to Oxford Dictionaries, criticism means “(1) the expression of disapproval of someone or something on the basis of perceived faults or mistakes, (2) the analysis and judgment of the merits and faults of a literary or artistic work” (Oxford Dictionaries 2013). Criticism is perceived as personal opinion of a “recognized critic” based on experience and intellectual procedures aiming at highlighting success and failures of a “significant” project. Aiming at the professional press and community, criticism utilizes specialized terminology, usually out of the reach of the public. Being limited to “visual/aesthetic concerns, such as form, composition, order, etc., but it typically does not cover the addressing of needs for major stakeholders in buildings,” as indicated by Davis and Preiser (Davis and Preiser 2012), architectural criticism had limited impact and value in the public realm. Recognition that architecture criticism is in a state of “crisis” is found in most parts of the world. According to Stead:

Local commentators commonly complain that Australian architectural criticism is “not critical enough”, and that it is characterized by mild, politely descriptive, aesthetic or formalist approaches. Springing from this are a whole string of further assumptions – that critics are not sufficiently objective, that they are biased by their own connections within the small and close-knit architectural community, that they are complicit with the commercial bias of the journals, that they are timid and afraid of litigation, and that for all of these reasons architectural criticism is as nauseatingly sycophantic as it is irrelevant and ineffectual.

(Stead 2003)

On the other hand, attempts were made to bring architectural criticism to the public realm by appointing critics to write columns in popular newspapers, but their rapid disappearance from daily newspapers sends an alarming signal. Although Vanessa Quirk commented that we might think that “The Architect Critic Is Dead” when critics like Paul Goldberger left their long life career in architecture criticism to other media empires (Quirk 2012), as Alan Brake argues, “all the blogs, websites, and publications that cover architecture and urbanism” created a new platform for architectural criticism (Brake 2013).

While architectural criticism has lost some ground in popular newspapers and magazines, architectural evaluation has grown in scientific and academic domains. It has become recognized as a legitimate research area worthy of receiving research grants and professional commissions. For example, POE was defined by Preiser et al. as “the process of evaluating buildings in a systematic and rigorous manner after they have been built and occupied for some time” (Preiser et al. 1988). Its focus on methods and process allowed it to be recognized as part of the scientific research domain. Yet, for many architects, professional magazines continue to be the major source of information and inspiration during the design stage. Also, the scientific language, terminology, and jargon used in evaluation research are not fully grasped by the average architect seeking useful information applicable in the design stage. Evaluation and criticism continue to be post facto activities aiming at finished products and they appear not to be useful during the design stage. This is largely attributed to the languages used in communicating results and recommendations that remain unfamiliar to the design profession. As argued by Preiser et al.:

It is acknowledged that criticism in architecture is not based in scientific inquiry and does not appear to have developed as a clear discipline with its own boundaries in both the Western and non-Western regions. Nevertheless, POE is increasingly accepted as part of the academic and professional activities ranging from the classroom to building commissioning now required by many governments and building authorities.

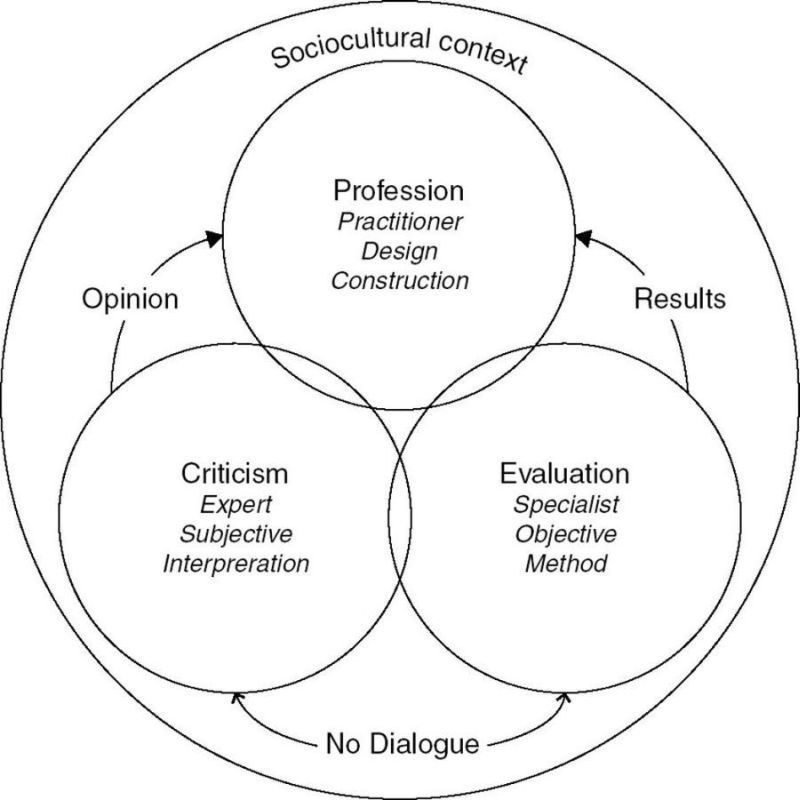

Do we need architectural criticism and evaluation to continue as separate realms or should they be combined in one? Davis and Preiser (2012) attempted to “bridge the gap between the affective and effective goals of architectural criticism” by exploring an “entirely new form of criticism that is instructive as both a tool to professionals and an explication of the built environment to the layperson beyond aesthetic platitudes” (Davis and Preiser 2012). To achieve integration between criticism and evaluation, they suggest: “For architectural criticism to be valid and comprehensive, the subjective or perceived criteria for criticism and the objective or measured criteria need to be brought together in a single coherent conceptual framework that can be communicated to others” (Davis and Preiser 2012).

Many factors affect the significance of criticism or evaluation studies. The first factor is the selection of what is studied or assessed. The location, size, and context of what is being studied are important factors. Individual buildings are the customary candidates for both criticism and evaluation studies. Aspects of study might include quantitative or/and qualitative factors such as aesthetics, function, performance, and energy consumption. While evaluation focuses on assessing performance, criticism focuses on impact, success and failures. The second factor is individuals, groups, or organizations that perform the study. Criticism is performed by an individual who has background, expertise, and knowledge allowing him or her to comment and express professional opinions about a building or projects. The critic might be a native of the place where the subject of study is located or might be a foreigner using the project to express an opinion or view point. As Davis points out in his chapter, “Criticism in its intended form, is a reasoned and thoughtful examination of a subject within an arc of an historical and philosophical context.” It suffers under the impulses of “the cacophony of media options and cultural histories that act as tools of estrangement.” Finally, the subject of study is usually a building or project of significance or public importance to the community. Critics rarely study projects used by poor or marginalized populations. The critic’s intention is to provide the professional community with evaluation, assessment, or appraisal of a building or a project. On the other hand, evaluation is usually performed by experts, or group of experts, focusing on the performance aspects of the building or project. Their diverse background allows them to evaluate different aspects of the project. Their aim is to provide feedback and assessment of the building performance from the point of view of the user, as well as its technical performance. The points of view expressed in these evaluation studies reflect specific users and buildings. While criticism focuses on project intentions, evaluation focuses on actual use and user feedback. The point of view of the critic or evaluator cannot be directly utilized in the design stage. While criticism is closer to the professional mode of work and thinking, its results remain remote from the architectural design process due to its specificity and limited generalizations.

Recognizing the socio-cultural context

While conducting various research studies in different contexts, several socio-cultural issues were identified. They ranged from mistrust of people in research and its benefits in changing their lives, and the use of research to harm them, to research as an accepted practice in a society. The political context might cause people to be suspicious of research efforts assuming that researchers are collecting information to harm them. In a village in Egypt’s countryside, people were hostile towards a research team, assuming they were collecting information and pictures of houses to inform authorities to demolish them.

“So what will be the benefit of your research for us?” asked one of my informants in a remote village in Nubia, Upper Egypt. He added, “We’ve received many researchers like you before. They all left and never returned again. Our life remained the same and never changed” (Mahgoub 1990). Should the researcher remain “objective” and “removed” from the situation in order not to fall into the trap of the anthropological syndrome called “going native”? Should he or she be “certain” that the research results will benefit his or her “subjects and informants” either as a “sample or population”? Should he or she remain a “stranger” and avoid becoming “native” (see Figure 21.1)?

In developing countries, research results do not help end users as they never reach authorities or decision-makers, and research is frequently influenced by bureaucracies and accepted practices. Phenomenological and qualitative research is usually considered “soft” and its results are unreliable. Research permits are limited to research that employs quantitative research only. While in most cases qualitative and ethnographic research reaches deep issues and gets in contact with people more than quantitative research, it is not considered as “valid” and “reliable” research. Research results challenge authorities’ agendas or assumptions. Policies established by centralized authorities direct research, imposing tight guidelines and areas of research priority. There is limited usefulness in the research results for the people who are affected by the socio-cultural context of funding and granting agencies. This continuing condition will limit research to certain areas and prohibits creativity, innovation, and exploration of new frontiers. It will also direct research away from daily concerns of people.

More drastic is the submission of Arab critics and architects to Western theories due to the absence of native theories and schools of thought. Al Naim describes it as:

personalizing the criticism approach away from its academic basis by not producing serious academic studies for the field of architecture, and thus, ending up in generations of Arabs who do not ask critical questions about their practices and processes. They are ‘submitting’ to whatever they receive and accept it blindly.

(Al Naim 2010)

This condition is a reflection of a larger cultural crisis in the Arab world that is fully dependent on foreign technologies, professionals, and critics.

FIGURE 21.1 Researcher and informant dialogue

Source: author.

FIGURE 21.2 Profession, criticism, and evaluation dialogue

Source: author.

The gap between research and practice has been recognized since the end of the twentieth century. Efforts to bridge this gap included the establishment of “InformeDesign,” “an evidence-based design tool that transforms research into an easy-to-read, easy-to-use format for architects, graphic designers, housing specialists, interior designers, landscape architects, and the public” (InformeDesign 2002–2005). InformeDesign recognized the need “to bring research and practice aspects of the design professions together. InformeDesign aimed to bring research from a vast array of reputable research sources to the design community that address those challenges” (InformeDesign 2002–2005). Yet it ceased to continue due to lack of funds and is now idle. The designers of the built environment face a multitude of complex challenges: resource, social, environmental, behavioral, and design in nature (see Figure 21.2).

Conclusion

Criticism and evaluation impact can be improved if they recognize their shortcomings in communicating useful results to practitioners and decision-makers. They should focus on providing “practical” information to designers during the pre-design stage. While they both have their successes and failures, they remain marginal to professional practice. They should recognize the socio-cultural, for both the subject of study and the person studying, as a major factor in shaping the results. Recognition of continuous changes in clients’ and users’ interest is intrinsic to their future success. Clients are either becoming more sophisticated, requiring more information and evidence that the design will satisfy their needs and ambitions, or they are becoming more helpless and have no input in what is being designed for them by the professionals and decided for them by decision-makers. If both criticism and evaluation re-recognize their base in the architecture profession, their results will be more useful and practical. While criticism needs to become more research based and apply rigorous and systematic methods, evaluation needs to be more critical and produce more relevant results to the profession. Criticism and evaluation need to initiate a dialogue to achieve mutual strategies useful for the profession.

References

Abdalla, G., G. Maas, J. Huyghe, and M. Oostra (2011) “Criticism on Environmental Assessment Tools. Proceedings from IPCBEE 2011.” International Proceedings of Chemical, Biological and Environmental Engineering 6: 443–46. Singapore: IACSIT Press.

Al Naim, M. (2010) Safar Al Omran [Urbanism Genesis]. Nadi Al Sharquiah Al Adabi.

The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language (2011) http://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=sociocultural+&submit.x=59&submit.y=32

Brake, G. A. (2013) “Criticism is Dead! Long Live Criticism!” The Architect’s Newspaper. http://archpaper.com/news/articles.asp?id=6605

Bürger, P. (2010) “Definitions and Limitations of Criticism.” OASE Journal of Architecture 81: 14–32.

Davis, A. T. and W. F. E. Preiser (2012) “Architectural Criticism in Practice: From Affective to Effective Experience.” International Journal of Architectural Research 6(2): 24–42.

Federal Facilities Council (2001) Learning From Our Buildings: A State-of-the-Practice Summary of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (FFC Report No. 145). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jannière, H. (2010) “Architecture Criticism: Identifying Object of Study.” OASE Journal of Architecture 81: 34–54.

John-Steiner, V. and M. Holbrook (1996) “Sociocultural Approaches to Learning and Development: A Vygotskian Framework.” Educational Psychologist 31(3–4): 191–206.

Oxford Dictionaries (2013) http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/criticism

Preiser, W. F. E., H. Z. Rabinowitz, and E. T. White (1988) Post-Occupancy Evaluation. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Quirk, V. (2012). “The Architect Critic Is Dead (just not for the reason you think).” ArchDaily. http://www.archdaily.com/223714/the-architect-critic-is-dead-just-not-for-the-reason-you-think/

Rendell, J. (2005) “Architecture-Writing.” Journal of Architecture 10(3): 255–64.

Stead, N. (2003) “Three Complaints About Architectural Criticism.” Architecture Australia 92(6): 50–52.