12

THE TACTILE LEGACY OF ALVAR AALTO AND ITS RELEVANCE TO CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE

Kenneth Frampton

Among the pioneers of the Modern Movement Alvar Aalto remains the one figure whose seminal contribution to the field seems just as valid now as it was at the end of his life. This claim may be justified on many levels, not least of which is the inherent sustainability of Aalto’s architecture, sustainable above all in his preference for using brick and wood which remain the two materials with the least embodied energy in terms of production. Apart from this attribute these materials would also ensure the social accessibility of his work and it is my belief that Aalto’s manner, particularly over the years from 1934 to 1968, was more accessible to the man-in-the-street than the architecture of any other pioneer whose work came to maturity over the same period. As Eduard and Claudia Neuenschwander were to demonstrate, in their study of the first decade of Aalto’s post-war work, in their book Alvar Aalto and Finnish Architecture of 1954, Aalto’s production was a symbiotic extension of Finnish environmental culture in every conceivable sense, encompassing not only his lifelong allusion to National Romanticism but also his recognition of the fact that the origin of Finnish vernacular culture was ultimately grounded in a perennial interface between wood, water and rock.

It was precisely Aalto’s sensitivity towards his native culture which enabled him to render his architecture accessible to society as a whole and it is this surely that is still one of the most fundamental challenges confronting the profession today, namely, how to continue with a liberative project of the Modern Movement, while also conveying a sense of security without descending into kitsch. Aalto recognized this challenge well before many of his contemporaries and it is my contention that through his biorealist corporeal vision of modernity Finland came closer than any other modernizing state to resolving this dilemma, particularly over the last two thirds of the twentieth century. In this regard, Scandinavian functionalism was always more nuanced than the normative aspirations of the Neue Sachlichkeit as this prevailed throughout the 1930s, particularly in Germany, Holland and Switzerland. This contrast between so called funkis manner and the productive preoccupations of the Neue Sachlichkeit was already manifest in Gunnar Asplund’s Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 which, as a subset of the international style, was softer in its syntax and thereby more humanly accessible than the Deutsche Werkbund Weissenhof Exhibition, staged in Stuttgart three years before. This shift exerted a decisive influence on Aalto as we may judge from his initial response to the Stockholm Exhibition:

The deliberate social message that the Stockholm Exhibition is intended to convey is expressed in the architectural language of pure spontaneous joy. There is a festive elegance, but also a childlike lack of inhibition about it all … this is not a composition of glass, stone and steel as a visitor who despises functionalism might imagine, it is a composition of houses, flags, flowers, fireworks, happy people and clean table cloths.1

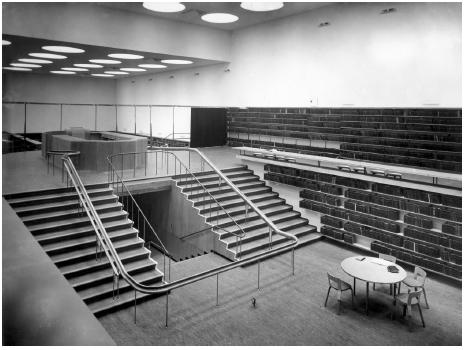

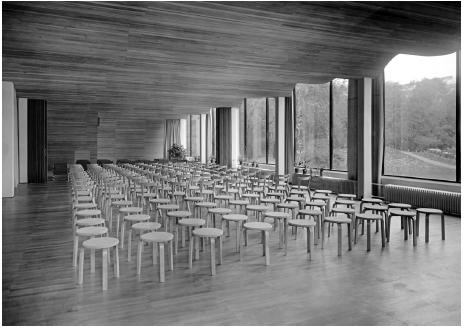

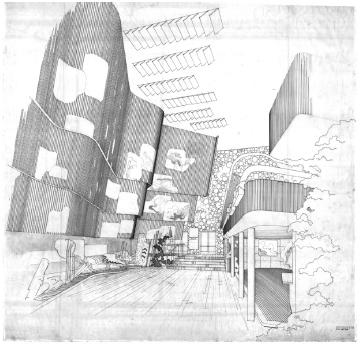

Aalto sympathized with the latent social democratic ethos as this had been conceived by the director of the Swedish Arts and Crafts Society, Gregor Paulsson. The funkis sensibility seems to have arisen out of a some kind of symbiotic exchange between Asplund and Aalto just prior to the Exhibition for with its cylindrical skylights, lacquered mushroom columns, wooden handrails, and louvered ceiling lamps, Aalto’s Turun Sanomat Building, realized in Turku in 1929 evidenced a subtly nuanced sensibility within the overall severity of its cubic form. In fact Aalto’s Turku building may have prompted Asplund to liberate himself from the rigid civility of Nordic Classicism not only on the occasion of the Stockholm exhibition but also in his Brandenburg department store, completed in Stockholm in 1935. This was the same year in which Aalto realized his Viipuri Library, the initial design for which had been influenced by Asplund’s Stockholm public library of 1926. With its cylindrical anti-glare skylights, ergonomic handrails, Artek timber furniture and its serpentine acoustic ceiling, the Viipuri Library achieved a new kind of tactile functionalism that went beyond the populism of the Stockholm Exhibition (Figures 12.1 and 12.2).

Figure 12.1 Alvar Aalto, Viipuri Library, interior photo; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

Figure 12.2 Alvar Aalto, Viipuri Library, interior photo; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

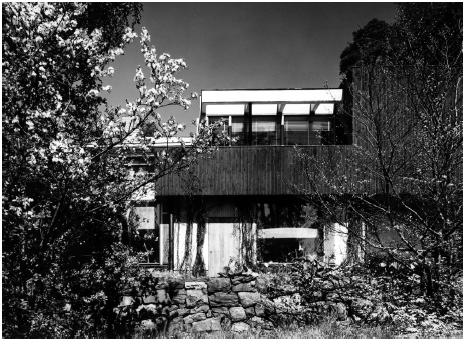

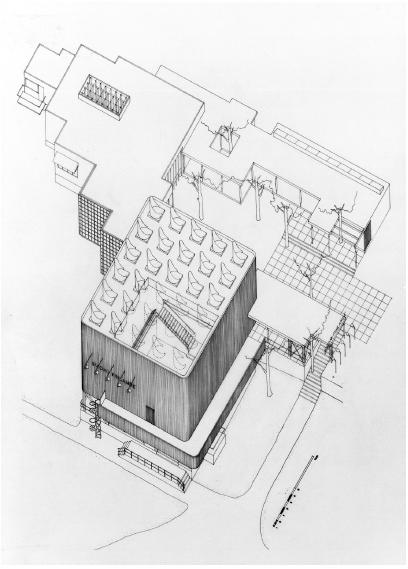

Aalto’s tactile approach to both form and material first emerges in his own house constructed in the Helsinki suburb of Munkkiniemi between 1934 and 1936 (Figure 12.3). Comprised of whitewashed load-bearing brickwork and vertical timber siding, this is for the first time when we will encounter this particular juxtaposition in his work, the juxtaposition of milled timber, the opposition that is between milled timber cladding and rough timber balustrading from which only the bark has been stripped; the two being brought together in conjunction with plate glass and a rubble stone walling. This modern reinterpretation of the Finnish vernacular will come more fully into its own with his Finnish Pavilion designed for the World Exhibition staged in Paris in 1937 (Figure 12.4). This last was built almost exclusively of wood consisted of single story open-sided gallery, which culminated in a top-lit exhibition hall clad, on all four sides, with ribbed timber siding. The exhibition, staged at the height of the Spanish Civil War, was followed in 1939 by the New York World’s Fair and by the outbreak of the Second World War. In Finland these events were accompanied by a three and a half month bitter struggle against the Soviet Union, the so-called Winter War, a conflict, which will be resumed in the so-called Continuation War of 1941 to 1945.

Alvar and Aino Aalto first visited the United States in 1938 and Alvar Aalto would return there in the following year to supervise the construction of the Finnish National Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. Aalto’s pavilion in New York was another tour de force in timber construction, which as an interior was virtually an inversion of the Paris pavilion (Figure 12.5). At the same time, the thematic was virtually identical, namely, the representation of Finland as a rising industrial nation, based on a forest economy and committed to a social-democratic program of modernization. In physical terms this pavilion was a fifty-two foot high cavernous space dominated by an undulating inclined wall made up of a reiteration of vertical timber patterns and divided horizontally into a geometrically progressive sequence of four successive tiers, respectively representing the country, the people, the workaday world, and, at the lowest level, the products of the national timber industry, which varied from the rolls of newsprint to skis, propellers and Aalto’s bent and laminated Artek furniture. Above this tactile display of industrial products on the ground floor, the various facets of Finnish life were represented by large blown up photographs of varying size and shape. There was something about the rhythmic dynamism of this montage that recalled El Lissitzky’s agit prop setting for the Soviet contribution at the International Hygiene Exhibition staged in Dresden in 1930. What was unique here, however, was Aalto’s particular approach to the plasticity of the space which, as with his famous Savoy vase of 1936, derived from his feeling for the organicism of the Finnish landscape inundated with lakes.

Figure 12.3 Alvar Aalto, Aalto’s Munkiniemi House, 1934 photo, image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

Figure 12.4 Alvar Aalto, Finnish Pavilion, Paris, 1937 axonometric view; image courtesy of Museum of Finnish Architecture

Apart from this vision of a mutually beneficial interplay between nature and culture, Aalto, like Gregor Paulsson, was convinced that a truly liberative modernity could not be achieved without the integration of architecture and design with radical social reform and it is this conviction no doubt that lay behind his traumatic disillusionment when the Soviet Union gratuitously invaded Finland in 1939. Around this time Aalto, together with Paulson and his wife, Aino Aalto, would become preoccupied with cultivating a Third Way between the totalitarianism of the USSR and the freewheeling rapacity of American capitalism. Their particular brand of welfare state humanism was to have been proselytized through publication of an international magazine entitled The Human Side, a project which, despite having selected topics and authors for the first issue, was totally eclipsed by the outbreak of the Second World War.

Figure 12.5 Alvar Aalto, Finnish Pavilion, New York, 1939 perspective; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

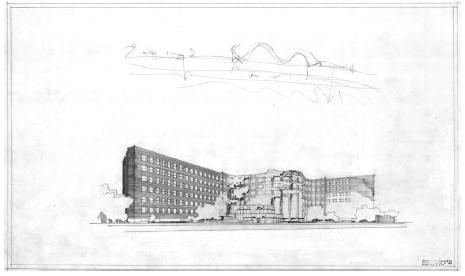

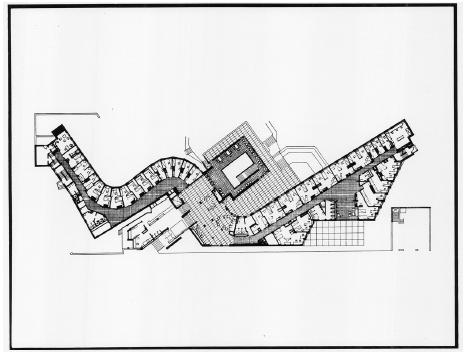

Aalto’s successive exhibition pavilions for the Finnish state exemplified this progressive ideology while, at the same time, affording him occasions on which to demonstrate the organic heterotopia of his emerging maturity, first, in 1937, in a quasi-constructivist reinterpretation of the Karelian vernacular, and second, in 1939, when he produced a mesa-like metaphor for the edge of a forest in the form of an undulating cliff-like face which will be later transposed into the brick escarpment of the Baker House dormitory block, completed to his designs in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1949 (Figures 12.6.a and 12.6.b).

Figure 12.6.a Alvar Aalto, Baker House, plan; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

Figure 12.6.b Alvar Aalto, Baker House, perspective; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

Aalto’s move into brick as the primary material came with the brick-faced pulp mill that he designed for Ahlstrom; a vast industrial plant built on a backwoods site in Sunila in 1938. However, this shift did not entail any kind of aversion to wood as we may judge from Aalto’s Otaniemi sports hall and the Karhula Glassworks Warehouse, both dating from the early 1950s and both demonstrating quite brilliant tectonic exercises in the use of timber structure. Much the same may be found in the numerous industrial structures that he built over this same period as in the timber clad, steel-framed Varkaus saw mill of 1946.

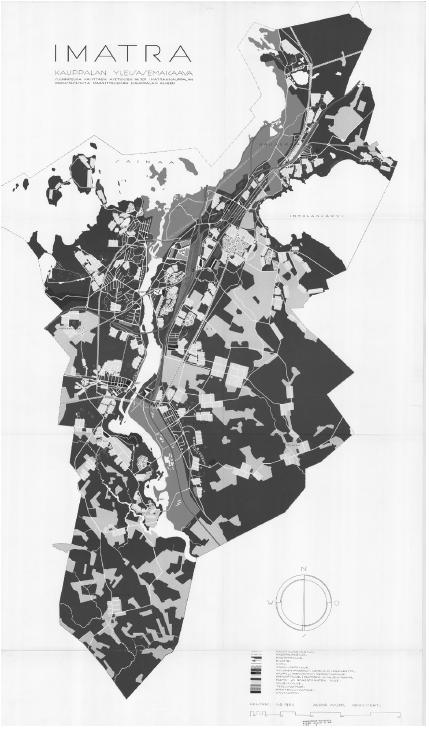

Aalto’s most comprehensive projection at this time in relation to Finland’s rapidly expanding timber industry was his regional plan for Imatra worked out over the years 1947–53 (Figure 12.7). In this and other regional plans of the period, Aalto developed his somewhat mythical concept of the “forest town,” as opposed to the Anglo-American Garden City as first fully exemplified in Unwin and Parker’s Hampstead Garden Suburb of 1905. In total contrast, Aalto’s Imatra plan posited a relatively dense cellular residential aggregation which would be integrated as interstitial form into an organic patchwork of arable land, densely wooded areas and industrial enclaves, the whole being fed by a continuous linear road and rail infrastructure, thereby establishing a continuous nature/culture mosaic in which anything as altruistically controlling and conformist as a public park would have been totally out of place.

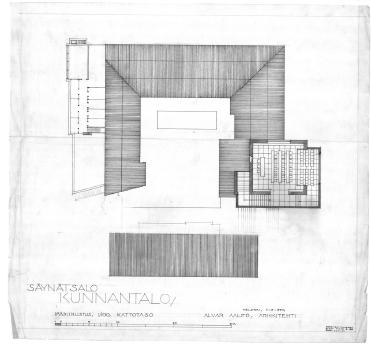

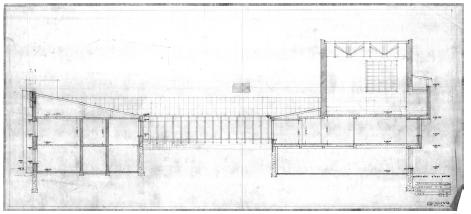

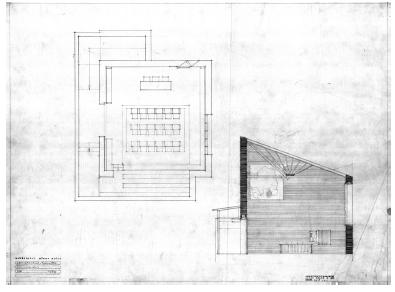

It was a sign of postwar austerity that Aalto’s next canonical building was not a luxury villa but a small municipal building, namely, the brick-clad Saynatsalo Town Hall which was the winning design of a competition held in 1949, the building being realized two years later. Comprising a spiraling mass-form which culminated in the mono-pitched roof of its council chamber, Saynatsalo, comprising both the town hall and the local library, was laid out around the square arena of an elevated atrium situated one floor above the general level of the street (Figures 12.8.a, 12.8.b and 12.8.c). This podium would be accessed by two different kinds of stairways, the one monumental in dark granite, and the other a roughly stepped approach covered with grass, where the rudimentary risers were made of split tree trunks held in place by stakes. Where the former, dressed in stone so as to signify civic deportment, brought one to the level of the public library and the municipal offices, the latter alluded to the vernacular roots, which were always lying just beneath the surface in Aalto’s architecture. That Aalto valued brickwork very highly is evident from all the industrial work that he built during this period and from the praise that he accorded to the masons who built Saynatsalo. Something of the Baltic vernacular was surely hinted at in the false crenulations of its brick walls and in the atypical twin timber trusses fanning out above the council chamber to support the purlins of the mono-pitch roof.

Figure 12.7 Alvar Aalto, Imatra town plan; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

This brings me to that which is still one of most fertile aspects of Aalto’s on-going legacy, namely, his proclivity from Saynatsalo onwards to treat almost every building as if it were a micro-landscape in itself and, further, by virtue of this intrinsic topographic inflection, to open the building not only to an organic grounding of the work in a specific site but also to the rhythmic reciprocal articulation, not to say animation of the site in terms of what is, in effect, nothing more than singular intervention. But beyond this, depending on the circumstances and the scale, Aalto would also conceive a potential civic intervention as a megaform capable of being read as an artificial land-form in itself.

Figure 12.8a Alvar Aalto, Saynatsalo, plan; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

Figure 12.8b Alvar Aalto, Saynatsalo, section A; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

Figure 12.8c Alvar Aalto, Saynatsalo, section B; image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

What is one of most surprising and refreshing aspects of this proposal, at least as we may perceive it in model form, is that the autoroute entry and the existing railhead are treated as part and parcel of the same plastic composition, as are the one-off cultural buildings to be built as a sequence on the other side of the Toölö Lake. Even more compelling perhaps is that the historic content of the city would have been incorporated into this large scale intervention had it been executed. Existing institutions such as the Parliament, the National Museum and the Olympic Stadium would have been harmoniously incorporated into the panoramic vision. In this scalar and strategic range, passing from the Imatra Plan to the Vogelweidplatz stadium and his automobile topographic proposal for the center of Helsinki, we have ample evidence of Aalto’s continuing relevance for the specific challenges facing the practice of architecture and urbanism today.

I have in mind Paul Ricoeur’s recognition of the continual uprooting of the late modern world where the challenge increasingly becomes, as he put it, how to become or remain modern and yet, at the same time, return to sources. Similarly, we have to recognize that the megalopolis is a universal condition that we have no choice but to come to terms with as a universal phenomenon. In this regard, it is increasingly clear that some form of landscape urbanism offers the most plausible generic strategy with which to overcome the loss of the historic city. Thus, Aalto’s informal linear city mosaic of Imatra may well serve as a valid strategic model, wherein urbanism is posited more as a critical ecological pattern than as any kind of coherent whole. And it is under a similar rubric that the one-off building, either as a megaform or as a more modestly scaled civic intervention, may yet be brought to yield unforeseeable catalytic ramifications for the future of urban form.

This, then, is the range of Alvar Aalto’s continuing legacy extending from the phenomenological subjective experience of relatively intimate continuing environments to the strategic potential for appropriate large scale interventions in which the ultimate aim is not some identifiable whole or norm but rather the confirmation of a fragmentary yet nonetheless relatively harmonious large scale organic process and prospect.

Notes

1 Alvar Aalto, “The Stockholm Exhibition 1930,” in Göran Schildt, Ed., Alvar Aalto in His Own Words (New York: Rizzoli, 1998): 72.