9

TOUGH LOVE

A study of the architecture of Pezo von Ellrichshausen

David Leatherbarrow

Love that has yielded to the right order can no longer be understood as craving and desire because its direction is not determined by any particular object but by the general order of everything that is.1

Hannah Arendt

In Built upon Love Alberto Pérez-Gómez linked together three concepts that can be said to be essential in any architectural work: project, program and promise. I have called them “concepts,” which they are of course, but they can also exist concretely and give durable form and legibility to spatial and social agreements (Figure 9.1). He addressed the interrelationships of these three terms in the second part of the book, where the meanings of the prefix pro were described.2

Project making, to start with the most obvious case, is essentially prospective. Projectum, the English word’s Latin stem, meant something cast or thrown forward. With respect to architectural drawing, Robin Evans captured this sense of the word very well when he described the construction of a perspective as a “projective cast.”3 Alternatively, one can think of the flight of a fisherman’s baited hook, sent on its way in the belief that a catch is somewhere “out there,” the wide target of the cast. Advance is also indicated by the term’s cognates: projectile, projection, projector, and so on. Yet, the advances to which Pérez-Gómez refers occur not only in space but time; pro indicates temporal progress as well as spatial projection. Priority can refer to phase or position, something anterior or in front of. Projects move forward in weeks, months, and years, just as they advance outwardly in feet or meters. As such, a project constitutes something like an offering, extended to another person or place, whereby relationships change. Donations of this kind often involve giving ones word – making a promise – that in turn inaugurates a program of activity or involvement. In architecture, narrowly defined, a program is a proposal for new ways of living in altered settings and spaces. Still another pro- word points to the enactment of a program and its promises: every project unfolds as a process, over which architects have no more than partial control. The full realization of a project, program, or promise is also conditioned – maybe largely so – by the pre-existing structures or order of the world in which it is to find its place and play its role. In the epigraph cited above, the world, “the general order of everything that is,” is the target of desires (projects) that have, Hannah Arendt says, “yielded to the right order.”

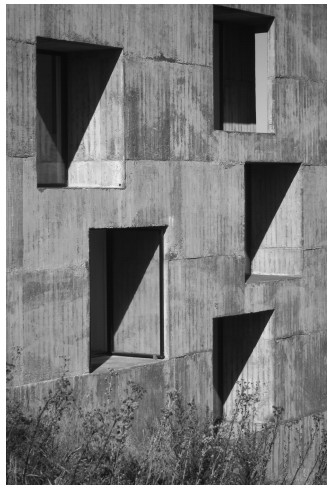

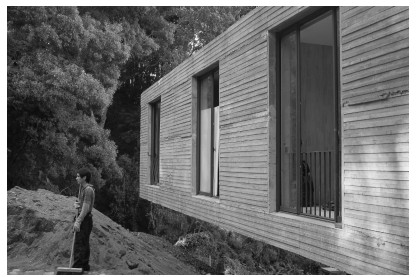

Figure 9.1 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Poli, 2002–5, side elevation (photo by author)

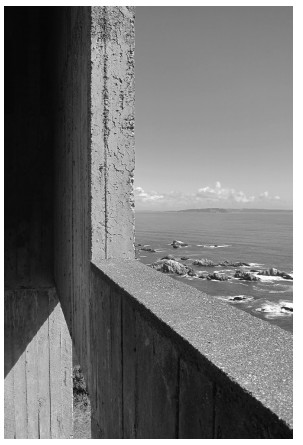

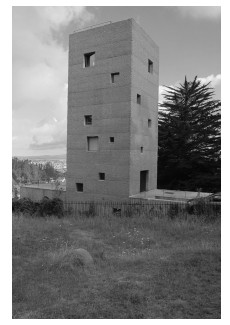

Figure 9.2 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Poli, 2002–5, window frame (photo by author)

“For love of the world” is the answer Arendt gave when asked why she had devoted her entire life to philosophy. So important was the theme that she first thought to use the Latin version of the phrase (amor mundi) as the title of the text ultimately published as The Human Condition.4 The world she had in mind was not, of course, the planet earth, not even the natural world; it was all of that plus the human order that had (and has) been discovered and established within it – including all of our buildings, cities, cultural institutions, stories, histories, laws, and so on. Another evidence of her long-standing concern with the adventures of affection is the title and subject of her first book, Love and Saint Augustine. The true correlative of desire, she argued, is something lacking in one’s life, something or someone wanted as a counterpart. A sense limitation is required for this experience – self-limitation especially, sensed at the edge or boundary of one’s abilities or capacity – and something beyond it, some image of richness or abundance, in a person, a place, or some wider quarter of the world (Figure 9.2). Anne Carson, in Eros: The Bittersweet, described this liminal situation under three interrelated headings: “Finding the Edge,” “Logic at the Edge,” and “Losing the Edge.”5 In architecture an analogous relationship exists between the needs of the work and the resources of the world, played out at the building’s borders, through elements that enclose and open the interiors, constructed of course, and defined geometrically. Were we to ask the architects whose work I will consider, Mauricio Pezo and Sofia von Ellrichshausen, why their buildings are defined so substantially, precisely, and resolutely, I suspect their answer would be some equivalent to Arendt’s for love of the world, for they, too, explore the spatial, social, and personal “logic at the edge.”

The geometries used by Pezo von Ellrichshausen seem simple, disarmingly so (Figure 9.3). In a time when formal experimentation often seeks novelty above all else, the plans and sections of these buildings appear out of season, at least initially. Yet, if a desire for something spectacular does not prevent us from looking at their work more closely, the designs reveal exceptional refinement, elegance, and inventiveness. Here is my opening question about their work: how can inventiveness occur when plans deploy familiar forms, forms that might seem to result from uncritical borrowing?

The square appears in the plan of many of these buildings, variously resized or adjusted proportionally, by doubling, adding or subtracting a half or the length of the diagonal – nothing new in that. Likewise axial symmetry, seen so often in this work, is an unfashionable but well-known instrument of plan arrangement; although the lines of composition in these layouts generally do not structure spatial passage, the main rooms of the Cien House and the mid-plan stairway of Arco House are exceptions. And finally, the nesting of smaller spaces within proportionate subdivisions of primary forms is an equally recognizable motif of compartition – Alberti, whose term I am using, argued for this procedure centuries ago. Assuming that the reuse of familiar techniques is not an end in itself, two explanations suggest themselves: either Pezo von Ellrichshausen intend their geometries to be representational in some way, or they are mechanisms of design technique. Nuanced differentiation shows that there is nothing mechanical about these arrangements. Nor does formal variation appear to be the aim, even if it is in evidence; rather, it is the result of precise attunement to the requirements of inhabitation and the opportunities of the location. If one says these plans are representational, it is because they anticipate and trace patterns of inhabitation, proportioning, one can say, the ratio between what the work lacks and the world supplies. But this kind of specification is only the first indication of their allegiance to the principle of amor mundi.

Figure 9.3 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Gago, 2011–12, windows of façade (photo by author)

The imitation of praxis (mimesis tes praxeos) is the principle that governs plot composition, according to Aristotle’s Poetics6 (see Figure 9.4). He was concerned with tragic drama, but the etymological ties between the words plot, plat, and plan suggest there is no mistake in applying his principle to architecture too. Art does not fashion likenesses of people and things, but of their behaviors, how they interact with one another and the world, their “performances,” which can be inspiring or disgusting, and everything in between. Action is the key. Again: drama does not imitate people but what they do; more exactly, what they should or should not do, which is why poetry is more true (to what life can be) than history, which only reports what has happened. Articulating their own emphasis on performance – but not in the narrow sense of the word that is common in today’s talk about high performance buildings – Pezo von Ellrichshausen’s buildings define enclosures not geometries, settings prepared to accommodate typical patterns of living, not create interesting plans and profiles. Similarly, lines of symmetry are lines of sight or movement. Further, nested forms cluster co-dependent purposes: cupboards buttress workspaces, for example, and closets support the use of bedrooms. When geometries are disciplined in these ways everyday life unfolds freely. Instead of requiring attention, the forms adopt a reticent stance, rather like a silent witness attending to some unselfconscious act of generosity – not of giving, but of allowing. Quiet but ready, provisioning in their buildings expect to be consulted only when the practices of dining, sleeping, conversing, or working need a little support – limiting their involvement to the anticipations and tracings I mentioned earlier.

Figure 9.4 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Cien, 2008–11, kitchen (photo by author)

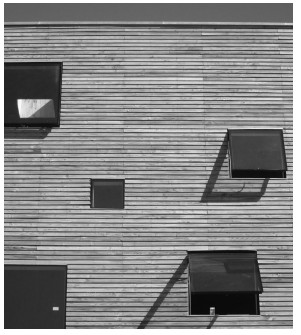

Support such as this seems effortless. What is more, these configurations show impressive economy. I do not mean the tight-fisted, sparing sort, but the elegance that results from a sharing of spaces that hold common interest. Proportioning is, after all, a way of giving each person or place the right portion or share, as in a meal. There are a very few corridors in these buildings; typically patios or entry halls combine and condense circulation requirements. Likewise, storage and service spaces are normally packed into wall thicknesses, making the space of the room as generous as possible. And the furniture that is not freestanding and centrally located is also immured into load-bearing depth – seating alcoves, benches, etc. – so that the movements of residing have the fewest constraints, as in the Abba, Gago, and Solo Houses, for example. The seating alcove of Casa Cien can serve as an example of these kinds of settings: a room within a room has been carved out of wall thickness, with its floor raised to seat-height and ceiling lowered to the right proportion, and equipped with all the instruments of domestic comfort and intimacy: concealed bookshelves of unequal depth to the left and right, a fireplace in the deeper niche, seating cushions, and a central window to the side slope. Its compactness allows corresponding openness to the room it adjoins, a much more ample setting, comparatively public, and emblematic of the composition of the whole, but nevertheless engaged with the alcove because the surfaces of both are clad with the same painted timber and their geometries are entirely congruent. One suspects that these economies resulted from painstaking studies of intervals and alignments, worked and reworked until their number and variations were reduced to fullness, fullness of potential. My main point is that the labor of design is not in service of pleasing geometry – certainly not that alone, even though it is pleasing – but the performances and practices the forms accommodate and represent (Figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Cien, 2008–11, sitting alcove (photo by author)

The part-to-counterpart relationship one sees in the plans of these projects is also apparent in their sections and elevations, but with a difference. What the program is to the plan, topography is to the section and elevation. With the word topography I mean land of course (terrain), together with its less weighty other half (climate, atmosphere, densities, and distances), but also the cultural aspects of a place (settlement patterns, histories, and characters).7 Obviously, content as rich as this exceeds what any single building cansupply – the “world” to which Arendt’s love and Carson’s “reach” referred. Once architecture’s essential poverty is observed, elements such as apertures become instruments of longing.8

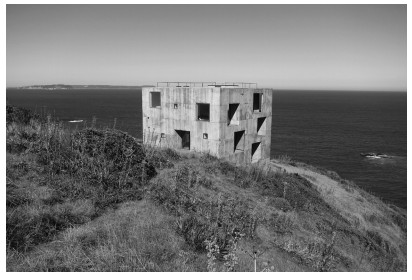

Many, though not all, of the sites on which Pezo von Ellrichshausen have built are sloped. In response, their projects adopt either of two siting strategies: rising above the fall of the terrain or cutting into it. This alternative was set out clearly decades ago by Marcel Breuer in Sun and Shadow, where he observed in a chapter called “Architecture in the Landscape” that a building is always and inevitably “a man-made thing, a crystallic, constructed thing … that should not imitate [the forms of] nature … but be a thing in itself.”9 The work’s artificiality meant either of two approaches to siting could be adopted: placing the house on columns, above uneven terrain, allowing passage below, or installing it into the land, elaborating its levels, and permitting free movement from inside to outside. Breuer admitted that he sometimes tried to combine these approaches. Pezo von Ellrichshausen have not used columns to raise their buildings above the land, but they do surmount a number of their sites. This strategy can be seen in the Sota, Abba, Guna, and Solo houses, for example. The stone and soil of Casa Guna’s site, for example, slopes into the small bay of a lagoon, while the platform on which the rooms have been distributed hovers above, its load-bearing walls drawn within, where they do their work quietly and in shadow (Figure 9.6). Pezo von Ellrichshausen have also taken an approach that is similar to Breuer’s second strategy, as can be seen in the Gago, Faro, Cien, Fosc, and Poli houses. Seen from the side, Casa Cien conceals a number of its stacked decks, within and above the site’s slope; but a single platform opens at the front to allow an entry stair to descend and extends at the back to expand the guest bedroom. Both siting methods lead to the multiplication of platforms, below, within, and above the building’s basic volume.

Another way to think of this is to view the building as a very big stairway with each of its platforms (inside or out) serving the function of a landing, connected to others and the wider milieu by a few intermediate steps, so that the building-stairway continues the approach and extends the departure. Pezo von Ellrichshausen have suggested as much in a comment they offered about the Cien House: “decisive coincidences such as the number of steps on a hill path nearby, an old cypress … , or even the elevation above sea level that defines [the] podium can explain this building’s silhouette” (Figure 9.7).10 Well, at least partly. The stairway sense of the section, its continuity within and extension beyond the building’s proper limits, allows the work’s involvement with natural and cultural dimensions of the ambient surround, dimensions that are not properly the building’s own (Figure 9.8).

Figure 9.6 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Guna, 2010–12, side elevation (photo by author)

Figure 9.7 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Cien, 2008–11, side view (photo by author)

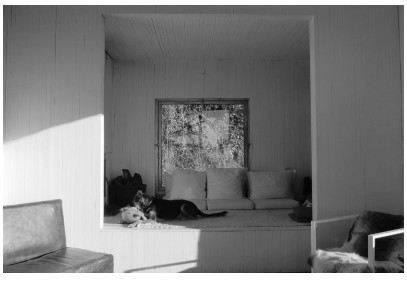

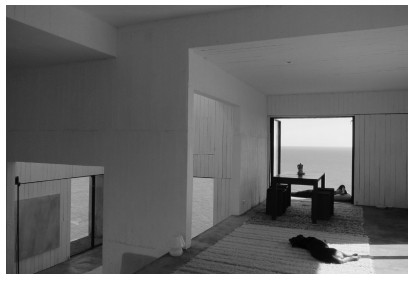

Something very similar happens with the apertures of these houses. Perhaps the most vivid case is the Poli House. Here the part-to-counterpart relationship unfolds by means of simply-shaped and sharply-cut openings in the building’s massive perimeter walls. It is hardly surprising to find walls as bulky as these in a landscape that suffers earthquakes with discouraging frequency. Yet, when inside this house, resistance to the wider landscape seems to have been the last thing the architects had on their minds, for the perforations in the perimeter welcome the site’s light, air, and sound so openly that the work seems best described as a receptacle, an open hand to all the world has to offer. The notion that the inside and outside should be connected is, of course, a commonplace of modern architecture. From the time of Le Corbusier’s “every inside is an outside” to contemporary arguments for “flowing space” we have been treated to countless attempts to remove what architecture seems particularly well-suited to provide: elements that divide, partition, and separate settings within the area on which one builds.11 Seeing the openings in these works as instruments of “flow” means overlooking their very hard edges, their sharp profiles, and their substantial back up, impassive as it is, resolute, and fully committed to resistance. The work opens itself to the world because all of its energies are concentrated on maintaining its own definition, not making any claims on what is not its own. Outward reach has not been accomplished because it was never attempted (Figure 9.9). Instead, the building is willing to wait – again like a silent witness – confident that the qualities of the world that will enrich its unpolished surfaces will make their appearance when they choose, according to their own schedule, with a force and direction they decide, according to the building’s expectations sometimes, often not, but always giving rhythm and amplitude to the life within its walls. Even though it argues for receptivity, the house does not adopt the restrictions that architecture called minimalist imposes on itself. Posited instead – through the procedures of construction craft as much as design and specification – are spaces and surfaces that resist what cannot be suffered and allow what will be enjoyed.

Figure 9.8 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Poli, 2002–5, interior (photo by author)

Figure 9.9 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Poli, 2002–5, interior (photo by author)

Rainer Maria Rilke defined love as an agreement that protects and nurtures individualities. It is, he said, just the opposite of a “quick commonality” that results from tearing down all boundaries. As if he were writing about concepts of connection and communication that are common in architecture, Rilke argued that “merging” is in fact senseless; when approximated it results in a “hemming in,” a denial of freedom. Differences and distances always exist, unyielding though they seem, tough though they may be. Far from being a problem, toughness of this sort allows for the emergence of a “marvelous side-by-side living.”12 The transactions between the work and the world instituted by the buildings of Pezo von Ellrichshausen advance the same thesis I think: caring for our lives and the environment by quietly and confidently staging their ever-changing interplay (Figure 9.10).

Figure 9.10 Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Casa Poli, 2002–5, exterior view (photo by author)

Notes

1 Hannah Arendt, Love and Saint Augustine, ed. Joanna Vecchiarelli Scott and Judith Chelius Stark (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996), 39.

2 Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Built upon Love (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2006), especially Chapters 8 and 9.

3 Robin Evans, The Projective Cast: Architecture and Its Three Geometries (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2000).

4 Elizabeth Yong-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt. For Love of the World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 324.

5 Anne Carson, Eros: The Bittersweet (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 30–52. The next two chapters, “Archilochos at the Edge” and “Alphabetic Edge,” place less stress on the spatial characteristics of this situation, more on its relationships to verbal expression and experience. The chapter titled “Reach” also addresses the spatiality of border experience, while the chapter called “Gone” elaborates its temporal order.

6 Aristotle, Poetics 1448a; for elaboration and commentary, see Ernesto Grassi, Die Theorie des Schönen in der Antike (Köln: Dumont, 1980), 125.

7 I have tried to develop these several senses of the term in Topographical Stories: studies in landscape and architecture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 1–16.

8 Kyra Stromberg has used an equivalent phrase, the window as a “place of longing” (der Sehnsuchtsort Fenster), in “The Window in the Picture – The Picture in the Window,” Daidalos 13 (1984): 59.

9 Marcel Breuer, “Architecture in the Landscape,” in Sun and Shadow (New York: Dodd, Mean & Company, 1955), 38–41.

10 Maurizio Pezo and Sofia von Ellrichshausen, “Cien House,” Harvard Design Magazine 34 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 110.

11 As with my brief comments on “compartition,” this sense of subdividing the space of the platform derives from Alberti’s account of what we now call plan making.

12 Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet (New York: Norton, 1934), 52ff.