16

TOWARDS AN ECOLOGY OF THE PALLADIAN VILLA

Graham Livesey

… our house would emerge as permeated from every direction by streams of energy… . Its image of immobility would then be replaced by an image of a complex of mobilities… .1

Henri Lefebvre

The villas by Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) in the sixteenth century for the terra firma, or mainland, region of the Veneto were designed primarily for the nobility of Vicenza and Venice. They were typically the centerpieces of working farms, and supplemented the incomes of the owners; they also provided a place for culture, recreation, leisure, and entertainment. The Palladian villa remains a distinct and comprehensively studied sub-type within the historical typology of the villa, and yet much of the scholarship surrounding the Palladian villa concentrates on the formal qualities of the buildings; relatively little has been written about how the Palladian villa was occupied. Here the functional organization of the villa and the use of furniture will be briefly studied in order to address the notion that all buildings and environments constitute ecologies.

An ecology is defined as the vital interaction between organisms and the environments they occupy, and is a concept that was devised in the mid-nineteenth century.2 Ecologies are measured in terms of how they function as habitats, which necessitates examining flows of populations, energy, water, waste, nutrients, and the like. Ecologies can be productive or not, and they are subject to a wide range of events. Ecologies constructed by humans also include technologies, economies, and socio-political systems, as humans modify and adapt to environments through the creation of clothing, objects, shelter, settlements and organizations. The overall behavior of an environment evaluates the productivity of that environment in terms of the energy employed, the distribution of nutrients and waste, the health of populations and also the economic, social and political dynamics of the system. Over time well-functioning ecologies support a complex range of species and tend towards dynamic balance, despite being continuously subject to changing arrays of forces.

The landscape ecologist Richard T.T. Forman has developed a method for examining the behavior of ecologies based on the “patch,” “corridor,” and “matrix.”3 This method examines the structure and performance of landscapes against various flows and population systems. Patches are defined territories or spaces that have a discernible composition, shape, size, edge characteristics, and adjacencies.4 A patch or territory, for example a room in a building or a small park in a city, has a latent functionality that is activated by populations that inhabit it and by the characteristics of the patch. In the case of architecture this has to do with how internal spaces are arranged, and how these relate to a larger context. Landscape ecologists employ the notion of “patch dynamics” to describe how a group of spaces might behave over time according to changing arrangements.

The behavior of a group of patches is influenced by the boundaries that both separate and unite adjoining territories or spaces. Boundaries, such as walls, and how they are composed, is also an essential factor in looking at the performance of an architectural ecology.5 Buildings are arrangements of spaces that are either functionally predetermined or open. The productivity of a building’s arrangement depends on the dynamics that occur within the internal spaces, and between the building and its context. Much of this depends on the size, shape, and location of a space, and the porosity of the boundaries that define that space. For example, walls in buildings function like membranes in that they filter a wide range of flows from heat, light, sound, and water, to animals, humans, and vegetation. Doors and windows are used in architecture as devices for crossing boundaries, and for regulating flows. The arrangement of spaces in a building and the interconnections between the spaces establish an ecological and functional potential. This is completed by how humans interact with the spaces, and how they modulate the environment through the use of furnishings and possessions.

Agostino Gallo, writing in 1566, describes in detail the pleasure of villa life including the benefits of fresh air and good food, the freedom and ease of living in the country, the enjoyment of watching peasants working, and the various activities the inhabitants enjoyed (hunting, conversing, reading, playing games, dining, and listening to music). His protagonist portrays a typical day in the villa:

First of all, I usually get up at dawn, and these days I join my companions at that hour to go out hawking… . Then we come home and often eat together… . Over the meal we talk about what we have discovered and caught … until it is time to rest or to attend to some necessary business. After that we often find ourselves getting together again to read, play cards or board games or chess, sing or play musical instruments… . After we have amused ourselves in this way, we walk in a group to visit this friend or that… .6

In particular this passage describes the social and recreational activities of noblemen enjoying the benefits of life in a late Renaissance villa. The women who also occupied the villa would have had a much more restricted existence, following very different patterns of living.7 This wide range of activities would have been supported by a host of servants whose labor was essential to operating the house and the farm.8

In his famous treatise The Four Books on Architecture (I quattro libri dell’architettura), originally published in 1570, Palladio, in his precise manner, elaborates on a villa in which the owner can pass his time “improving his property and increasing his wealth through his skill in farming,” and enjoy the benefits of life in a rural setting.9 The siting of the villa as part of a working farm was a crucial decision, and despite the lack of site drawings in Palladio’s oeuvre, contemporary studies demonstrate how carefully he located the villas.10 In siting the villa and outbuildings, and arranging internal spaces, Palladio was very conscious of factors such as access, wind, orientation to the sun, views, and less commodious factors such as dampness.11 A range of outbuildings, including the barchessa, either attached to the villa, or not, would have accommodated servants, animals, implements, and storage. In the flat landscape of the Veneto the villas were typically located facing a river or canal; this landscape had been engineered for some time in order to provide drainage, irrigation, and transportation systems.12 Ultimately, the siting of the building and the arrangement of the internal spaces contribute to the ecological effectiveness of a design.

The internal organization of the villa that Palladio developed responded precisely to the needs of his clients, judging from the popularity of his designs. Palladio’s villas followed a repeating pattern that organized rooms according to public (entrate, sale), semi-private (stanze, camere, camerini), and servant’s areas. The servants’ working spaces were typically arranged on the lower level with kitchens, cellars, and the like, while the main rooms were formally grouped on the piano nobile, which was elevated above ground level, around the main sala; the upper mezzanine levels were typically used as granaries and servant’s quarters.13 The piano nobile was sandwiched between the working, or less noble, areas of the house, internal stairs were discretely hidden within the fabric of the villa to accommodate the functioning of the villa, and external stairs typically provided dramatic access to the loggia from the estate.

The loggia was a vital element in the house working in tandem with the sala (Figures 16.1 and 16.2), or main hall, as it provided a transitional space between interior and exterior and was used for leisure, dining, and viewing the surrounding countryside.14 The sala (and entrances), as the most public space in the house, would have been used mainly for entertaining, conducting business, and for parties, banquets, performances, and weddings, and was typically a large formal room. The other, more private, rooms (stanze, camere) were equally distributed on either side of the public spaces and were multi-functional.15 The Palladian villa plan is characterized by its careful and symmetrical arrangement of spaces within a controlled form, akin to that of the human body. To some extent the organization of the villas reflected the arrangement of the palaces Palladio’s clients occupied in Vicenza and Venice, the Venetian palace being formally organized on the piano nobile level around the portego.16 Palladio writes of convenience, that it “will be provided when each member is given its appropriate position, well situated, no less than dignity requires nor more than utility demands; each member will be correctly positioned when the loggias, halls, rooms, cellars, and granaries are located in their appropriate places.”17 The rigorous “systematization”18 of the villa plan was a new aspect of Palladio’s designs, as was the controlled balancing of the facades and placement of openings (Figure 16.3).

Figure 16.1 Andrea Palladio, Villa Godi (1537), view from loggia (image courtesy of Johannes Niemeijer)

Figure 16.2 Andrea Palladio, Villa Pisani (1543–45), view of sala or main hall (image courtesy of Johannes Niemeijer)

Palladio, through the establishment and refinement of the villa plan was creating a series of spaces, or an ecology, that responded to both internal and external forces. The differing sizes of rooms (small, medium, and large) were suitably arranged, proportioned, and connected in order that they can be “mutually useful.”19 In his treatise, Palladio writes:

The small ones [rooms] should be divided up to create even smaller rooms where studies and libraries could be located, as well as riding equipment and other tackle which we need everyday and which would be awkward to put in the rooms where one sleeps, eats, or receives guests. It would also contribute comfort if the summer rooms were large and spacious and oriented to the north, and those for the winter to the south and west and were small rather than otherwise, because in the summer we seek the shade and breezes, and in the winter, the sun, and smaller rooms get warmer more readily than large ones. But those we would want to use in the spring and autumn will be oriented to the east to look out over gardens and greenery. Studies and libraries should be in the same part of the house because they are used in the morning more than at any other time.20

Figure 16.3 Andrea Palladio, Villa Pisani (1543–45), view of facade facing courtyard (image courtesy of Johannes Niemeijer)

From this quote it is evident that Palladio very carefully oriented each of the rooms; it can also be deduced that the occupation of spaces shifted according to the seasons and times of the day. The size, shape, and proportion of rooms were vital to the functioning of the house and the harmony of the architecture, as was the relationship between rooms and the outdoors, as precisely determined by the placement and size of doors and windows.21

Beyond the design and arrangement of the rooms in the villa, are the vital connections between spaces and the site itself. In the treatise Palladio also devotes some text to describing the size, location, and ornamentation of doors, windows, and stairs. For example, writing about windows, he states:

One should, therefore, take great care over the size of the rooms which will receive light from them [windows], because it is obvious that a larger room needs more light to make it luminous and bright than a small one; and if the windows are made smaller and less numerous than necessary, they will be made gloomy; and if they are made too large the rooms are practically uninhabitable because, since cold and hot air can get in, they will be extremely hot or cold depending on the seasons of the year, at least if the region of the sky to which they are oriented does not afford some relief.22

The attention to creating a harmonious whole, through the arrangement of spaces and the careful design of openings in walls, remains a hallmark of the Palladian villa. Despite the seeming neutrality and formality of the spaces, the various rooms that comprised the living rooms of the villa were carefully sequenced and each had distinctive qualities based on size, shape, and location.23 The villas were normally occupied during the warmer seasons, particularly during the planting and harvesting months. Activities on the piano nobile level of the villa included sleeping, dressing, eating, socializing, recreation, study, entertaining, and working; each of these uses required spaces, furniture, and other objects.24 The use of the rooms would vary, depending on who occupied the house, with any of the larger stanze/camere able to be a bedroom.25 When not occupied, the villas would have been relatively bare except for beds, and a few remaining items; the smaller rooms that were used as libraries or studies likely retained possessions throughout the year.26 Therefore, vital to the functioning of the villa was the employment of furniture, which allowed for the continuous rearrangement of the internal spaces; a defined group of spaces to be given a functional flexibility that allowed the entire group of spaces, or the dynamic of a group of patches, to be reorganized, or adjusted to changing ecological factors.

As Jean Baudrillard points out in his book The System of Objects, objects employed in traditional everyday life involved forms of embodied energy, energy that came from human labor and animals.27 Baudrillard writes, that in traditional, or pre-industrial settings:

Man’s profound gestural relationship to objects … epitomizes his integration into the world, into social structures… . We cannot help but admire scythes, baskets, pitchers or ploughs, amalgams of gestures and forces, of symbols and functions, decorated and stylized by human energy and shaped by the forms of the human body, by the exertions they imply and by the matter they transform… .28

These objects, including furniture, necessarily engage in the exertions and gestures of the human body and its involvement in space. It can be inferred that furniture mediates between ourselves and the spaces we inhabit, engages in a variety of energy flows, and allows for the creation and maintenance of ecologies. Baudrillard notes that objects in traditional systems were based on human efforts that were “embedded in human relations.” Similarly, the occupants of the Palladian villa, through their own actions and those of servants, participated in an ongoing negotiation with their environment through architecture and its furnishings. J. Macgregor Wise has described the creation of home, or habitat, as the continuous “organization of markers (objects) and the formation of space… . Home can be a collection of objects, furniture, and so on that one carries with one from move to move.”29 He suggests the arranging of objects, the organizing of space, and the presence of family and friends, is part of the identity making associated with home. As Wise states, the creation of home is a continuous activity that occurs everywhere we go, through “the arrangement of objects, practices, feelings and affects.”30 The flows of energy in a house create both harmonious and conflicted conditions, aided by the arranging of furniture, or the continuous creation of “home.”31 Domestic actions participate in a wide range of flow patterns and continuous exchanges of energy.32

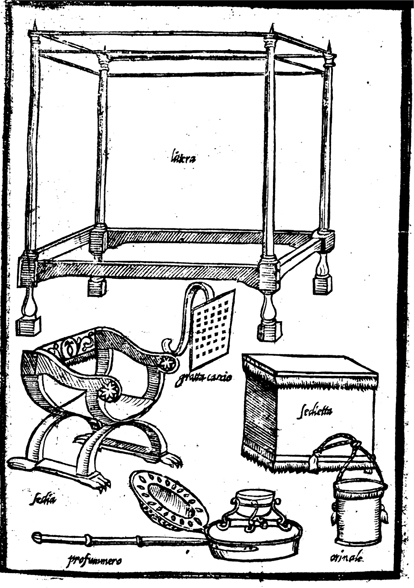

The owners of Palladian villas would have brought their furniture (móbili) and smaller personal items with them on each visit by cart or barge, packing these up when returning to town (Figure 16.4).33 This supported the adaptability of the internal spaces. Discussing the camere, or secondary rooms, found in Venetian palaces, Patricia Fortini Brown notes that they were spaces primarily used for sleeping, being occupied by beds and fireplaces. However, they had further functions:

The camere were also used for dining, for small formal dinners and for large banquets when guests spilled over from the portego, as well as for everyday meals during cold weather… . Tables on trestles, which could easily be set up in different rooms, were the norm in this period. Wall hangings, table linens and other objects were moved around as needed.34

Figure 16.4 A Renaissance bed, chair, stool, urinal and incense burner in Bartolomeo Scappi, Opera dell’arte del cucinare, Venice, 1570

One must assume that the secondary rooms in the Palladian villas were used in a similar manner. Beds would have occupied the spaces, and would not have been moved back and forth between villa and palace like the smaller furnishings (tables, chairs, stools, benches, chests, etc.). Beds were often the center of the house during the Renaissance, and were often shared, being “important sites for sociability.”35 Brown notes that after the bed, the chest was the most important piece of furniture in the Venetian camere of the period, and like the room itself, was multi-functional in that it provided storage (for clothing, linen, books, and small items), acted as a seat, could be used as a table, and provided a display surface for a runner or carpet.36 Chairs, tables, and a variety of fabrics would have completed the furnishings.37 Beyond the sleeping and dining functions, these spaces would also have been used as work and social places for women. Servants would have also been engaged in setting up rooms upon arrival, rearranging them as needed, and packing up for the return to Venice or Vicenza.

Life in the villa, despite the emphasis on rural tranquility, would have been busy, supported by the daily activities of served and servants. Much of the functioning of the villa would have depended on the interaction of spaces and flows of organisms, energy, air, water, nutrients, waste, and the like. The organization of building would have both enhanced and negated flow patterns. In particular, flows of energy are active in all aspects of villa from the embodied energy found in the material aspects of the house, to the active and passive energy systems, and the energy of the daily routines of living. As suggested above furniture plays a vital role in continuously modulating the various interior and exterior environments. This involves managing flow patterns, creating new ones, and dealing with the inevitable forces of inefficiency in the system.

The basic design of the Palladian villa appears to have been successful in meeting the needs of the Venetian and Vicentine clients, and has been a source of inspiration for subsequent generations of architects. Despite the symmetry of the villa plan, each room has particular qualities based on its size, shape, location and adjacent relationships (internal and external); when combined, this established a complex set of potentials. Palladio was sensitive to the specific needs of his clients, and to the concept of the rooms being multi-functional. Furniture was truly mobile and was used to continuously adjust the spaces of the house to changing users and to the seasons. In other words a productive relationship between furniture (móbili) and building (immóbili) was established. This resulted in a creative use of space, negotiated through changing furniture and spatial arrangements, rarely found in modern architecture.

As a repeating group of spaces, the patch dynamics of the Palladian villa was supported by the siting of the villa, and the ability on the part of the users to move functions around in the various spaces of the building. The Palladian villa balanced urban and rural life, and responded to the landscapes and climate of the Veneto. The villas were simple and relatively inexpensive to build, and they reflected Palladio’s late Renaissance classicism and inherent analogies to the human body. The Palladian villa was a formal and repeating arrangement of rooms and elements guided by both urban and agricultural factors, that was then adjusted continuously in response to client needs and site forces. The villas brought together material elements (building, furniture), flows (air, water, energy), bodies (clients, servants, visitors), languages (speech, codes of behavior), and territorialities (rooms, landscapes) into a dynamic construct.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors for their input in developing the essay, Dr. David Monteyne for providing insightful comments on a late draft, and Johannes Niemeijer for graciously giving permission to reproduce images originally published in Palladio, the Villa and the Landscape (Basel: Birkäuser, 2011), co-authored with Gerrit Smienk.

Notes

1 Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. D. Nicolson-Smith (Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd., 1991), 93.

2 The term “ecology” was devised in 1866 by the German scientist Ernst Haeckel.

3 See Richard T.T. Forman, Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

4 Ibid., 43–142.

5 Ibid., 145–176.

6 Agostino Gallo, “The Advantages of Villa Life,” in James S. Ackerman, The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 131.

7 See Joanne M. Ferraro, Venice: History of the Floating City (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 79.

8 See Guido Guerzoni, “Servicing the Casa,” in At Home in Renaissance Italy, ed. Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis (London: V & A Publications, 2006), 146–151.

9 Andrea Palladio, The Four Books on Architecture, trans. Robert Tavernor and Richard Schofield (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997), 121.

10 See Gerrit Smienk and Johannes Niemeijer, Palladio, the Villa and the Landscape (Basel: Birkäuser, 2011).

11 Palladio, The Four Books, 121–122.

12 See Denis Cosgrove, “Platonism and Practicality: Hydrology, Engineering and Landscape in Sixteenth-Century Venice,” in Water, Engineering and Landscape, ed. Denis Cosgrove and Geoff Petts (London: Belhaven Press, 1990), 35–53.

13 See Paul Holberton, Palladio’s Villas: Life in the Renaissance Countryside (London: John Murray, 1990), 206–209, 229.

14 See Paolo Portoghesi, The Hand of Palladio (Turin: Umberto Allemandi & Co., 2008), 89–96. See also Palladio, The Four Books, 56–57.

15 Palladio, The Four Books, 57.

16 See Patricia Fortini Brown, Private Lives in Renaissance Venice: Art, Architecture, and the Family (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004).

17 Palladio, The Four Books, 7.

18 Rudolf Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1971), 70.

19 Palladio, The Four Books, 78.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid., 60–61.

22 Ibid., 60.

23 Holberton, Palladio’s Villas, 208–209.

24 See Robert Woods Kennedy, The House, and The Art of Its Design (New York: Reinhold Pub. Corp., 1953), 132–133.

25 Holberton, Palladio’s Villas, 225.

26 Ibid., 226.

27 Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects, trans. J. Benedict (London: Verso, 1996), 48.

28 Ibid.

29 J. Macgregor Wise, “Home: Territory and Identity,” Cultural Studies 14, no. 2 (2000): 299.

30 J. MacGregor Wise, “Assemblage,” in Deleuze: Key Concepts, ed. Charles Stivale (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 2005), 79.

31 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Eugene Rochberg-Halton, The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 86.

32 Ibid., 195.

33 Holberton, Palladio’s Villas, 225. See also Sir Harold Acton, “Introduction,” in Peter Lauritzen, Villas of the Veneto (London: Pavilion Books, 1988).

34 Patricia Fortini Brown, “The Venetian Casa,” in At Home in Renaissance Italy, 58–59.

35 Elizabeth S. Cohen and Thomas V. Cohen, Daily Life in Renaissance Italy (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 221–222.

36 Brown, “The Venetian Casa,” 61.

37 See Cohen and Cohen, Daily Life in Renaissance Italy, 221–224.