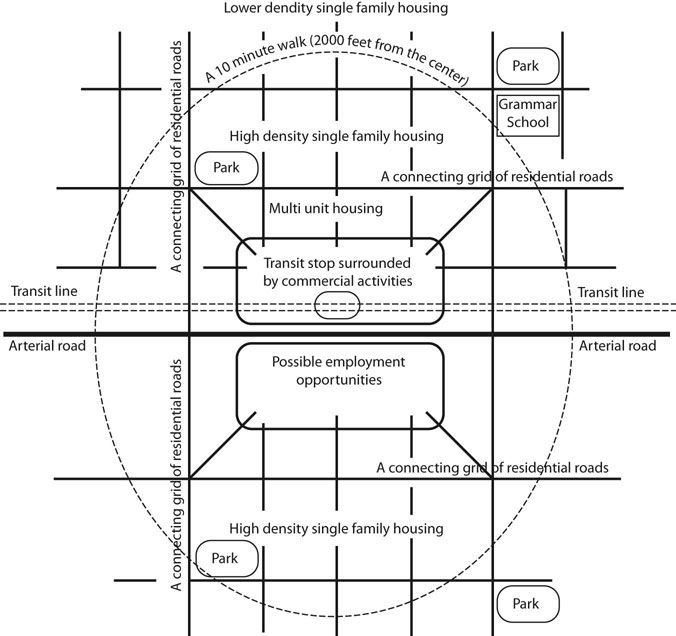

Transit oriented development (TOD) has overlapping goals with New Urbanism. However, transit oriented development is more focused on how the transit system relates to the development. The guidelines call for commercial and employment uses located near the transit stop, so that the rider gets off the light rail in a town center. The residential development around the town center needs to have enough density to support the town center and the transit stop. The average density is 18 units to the acre made up of a mix of 26, 16, and 10 dwelling units per acre with the higher density near the commercial core. All of this is located within a 10 minute walk to the transit stop (Figure 30.1). It is envisioned that there is a range of TODs with the more urban TODs along the main transit line with a relatively large commercial core, down to neighborhood TODs with a smaller commercial core and a higher percentage of residential development. The neighborhood TODs would be located on feeder transit lines. The TODs are a high density area, so public parks are a necessary part of the mix. Small and medium size parks need to be sprinkled around the development. The urban core should have civic buildings. Secondary areas, extending out about one mile from the commercial core of the TOD, contain mostly single family houses. This additional population helps support the commercial development and the transit stop (Calthorpe 1993, 56–61). The TOD, at 20 units per acre, has about 2,800 households. The secondary area, at 10 units per acre, has about 20,000 households.

Neighborhood TODs should have a mix of 10–15 percent public spaces, 10–40 percent core commercial, and 50–80 percent housing. Urban TODs should have 5–15 percent public spaces, 30–70 percent core commercial, and 20–60 percent housing. The neighborhood TODs located on feeder transit lines should be located so that the transit time to the urban TOD, where the main transit line is located, is about 10 minutes, which is about 3 miles. In order to achieve the residential density necessary to populate the TOD with enough households and provide choices for the residents, a mix of residential units is necessary. The mix should include apartments and condominiums, townhouses, duplexes, and single family houses. The street pattern in the TOD needs to be a grid of some sort providing multiple paths to the core commercial area and transit stop. This grid needs to extend out into the secondary area surrounding the TOD. Buildings both commercial and residential should create a streetscape. Commercial buildings need to face directly onto the street, with parking on the street and parking lots if necessary in the center of blocks (Figure 30.2). Residential units should also create a street presence, with small front yard setbacks and porches to create a friendly community environment. In order to reinforce the vitality of the core commercial areas of the TODs it is necessary to space them out at least one mile apart, and the zoning should not allow strip commercial development along the arterial roads that connect the TODs.

FIGURE 30.1 Transit Oriented Development (TOD) creates a walkable neighborhood around a commercial core with a transit stop at its center.

Source: Calthorpe 1993.

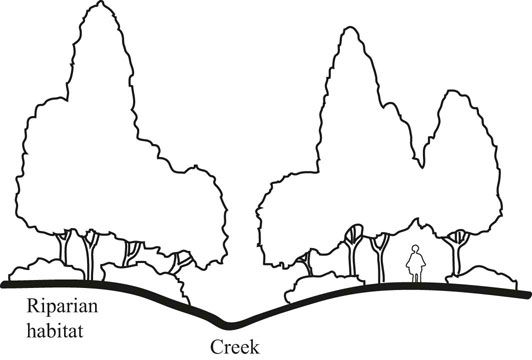

Existing landscape drainage, wetlands, and creeks need to be respected and can be incorporated into the open space of the development (Figure 30.3). Indigenous plantings create a pleasant and easily maintained landscape (Calthorpe 1993, 62–75).

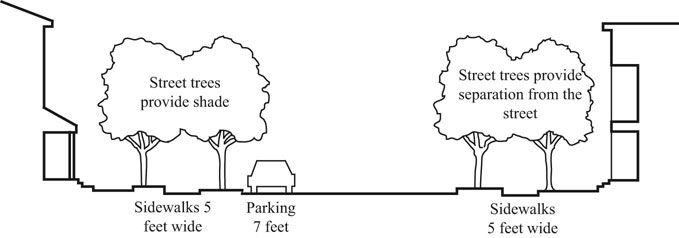

FIGURE 30.2 In the commercial core of the TOD the buildings need to front on the street with generous sidewalks and street trees.

Source: Calthorpe 1993.

FIGURE 30.3 The urban layout of the TOD needs to respect drainage land and drainage patterns. Creeks and wetland areas can be part of the park open space needs of the community.

Source: Calthorpe 1993.

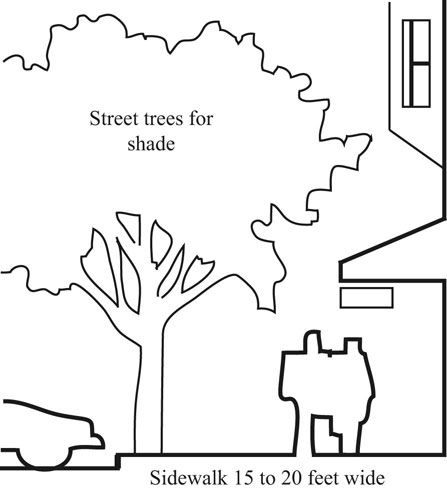

FIGURE 30.4 Sidewalks protected by street trees and parallel parked cars create a pleasant walking environment.

Source: Calthorpe 1993.

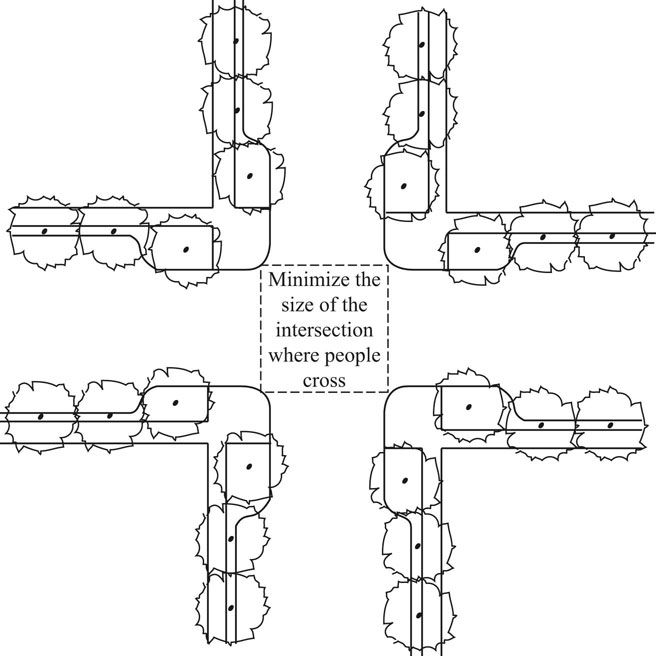

FIGURE 30.5 At corners, sidewalks need to widen out to the parallel parking line to minimize the size of the intersection. This makes crossing the street easier and slows cars down.

Source: Calthorpe 1993.

Parks of 1 to 4 acres need to be placed within a few blocks of everyone living in the TOD. Streets should be narrow enough to slow traffic. Street trees, spaced so that their canopies touch, create shade in summer, and, located between the sidewalk and the road, provide security for the sidewalk. Sidewalks should be a minimum of 5 feet wide, which lets two people walk side by side. On street parallel parking provides another buffer between the pedestrian and the moving cars on the street (Figure 30.4). At intersections, the sidewalk should widen out to the depth of the on street parking so that pedestrian crossing distance at the intersection is minimized (Figure 30.5). Larger parks with playing fields should be located on the boundary between the TOD and the secondary area. This boundary zone is also a good location for schools. A village green and a transit plaza should be about 2 acres in size and be located at the locus of the transit stop and the core commercial area. The transit stop needs to let residents off at the transit plaza with the core commercial shops in near proximity. Parking lots next to the transit stop are inappropriate. The intent is to create a walking environment. If parking is required it needs to be placed in the center of blocks away from the transit plaza. Kiss and ride drop-offs also need to be located away from the transit stop to avoid excess automobile traffic disrupting the pedestrian intent of the transit plaza and core commercial area (Calthorpe 1993, 87–106).

The overarching intent of transit oriented development is to create a denser living environment coordinated with an urban transit system. Urban households use 71 million BTUs per year for transportation and 80 million BTUs for running the household. Compare this to a suburban household that uses 237 million BTUs for transportation and 162 million BTUs for running the household (Calthorpe 2011, plate 3).