8

Devotion

The devotional functions of churches were frequently important in their design and remained significant throughout the period studied here. The emphasis on the liturgical movement in writing on church architecture at the time and since has tended to obscure this feature of post-war church architecture, a highly distinctive aspect of Roman Catholic culture in post-war Britain. The liturgical movement contrasted the liturgy with popular devotions, which were viewed as motivated by individual piety and sentiment more than reason or doctrine. For Guardini, the liturgy’s ‘sense of restraint’ and rich symbolic world made it a higher form of worship than pious devotions.1 Yet Guardini argued that devotions were still important, even necessary, and could be improved through the influence of liturgy. Later, the emphasis on liturgy in church architecture marginalised devotional features in churches, as the ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ implied:

The practice of placing sacred images in churches so that they may be venerated by the faithful is to be firmly maintained. Nevertheless, their number should be moderate and their relative location should reflect right order. Otherwise they may create confusion among the Christian people and promote a faulty sense of devotion.2

Liturgical movement writers could be scathing about the proliferation of statues in churches, doubting their efficacy in inspiring devotion.3 Decades later, however, a perceived loss of devotional imagery and ritual began to be felt with nostalgia, becoming a frequent criticism of the Second Vatican Council. There had been, it was thought, a ‘widespread collapse of the older devotional system’, as distinctive Catholic iconography had been replaced by banal and generic images.4

By the 1970s, many clergy were cautious with statuary. St Aidan in Coulsdon, south London, by Burles, Newton & Partners, for example, was spartan and lacked conventional imagery or indeed any special place for it. A small figurative crucifix by Dunsten Prudens was suspended in the Blessed Sacrament chapel, and a processional cross was placed behind the altar, the only image canonically required in a Catholic church. On a side wall towards the rear of the nave was the only other figure besides the discreet Stations of the Cross, a sculpture of the Virgin and Child. Beneath it was the stand for placing candles to accompany prayer; but the statue was attached high up on the wall, precluding the pious intimacy of private prayer in a conventional side chapel. Moreover the figure itself was unfamiliar, primitive in feeling and made of black bronze by a Swiss Benedictine artist, Xaver Ruckstuhl, in the style of the altar and other furnishings he designed for the church and its reform-minded parish priest, Kenneth Allan (Figure 8.1).5 Coulsdon was unusually ascetic for a parish church, however; most had at least a separate Lady chapel.

8.1 St Aidan, Coulsdon, London, by Burles, Newton & Partners, 1966. Sculpture of the Virgin and Child by Xaver Ruckstuhl. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

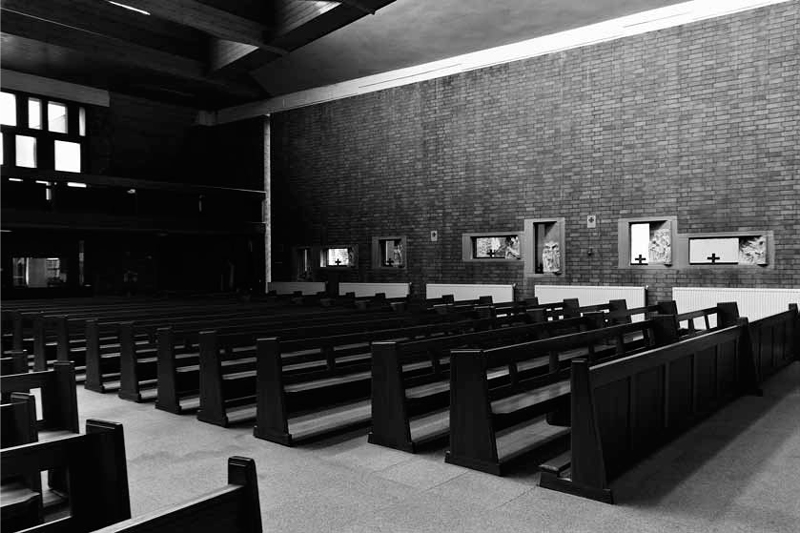

8.2 St Clare, Blackley, Manchester, by Weightman & Bullen, 1956–58. Mosaic of St Clare by George Mayer Martin; Stations of the Cross by David John. By permission of David John. Photo: Ambrose Gillick, 2012

Before the Second Vatican Council, churches normally had chapels or niches along the sides of the nave containing statue shrines; side altars were placed at the heads of each aisle dedicated to the Virgin Mary, St Joseph or the Sacred Heart, while statues of lesser saints were placed elsewhere. At Weightman & Bullen’s St Clare in Blackley, for example, the Lady altar was placed at the front to the left of the sanctuary, the Sacred Heart to the right, and three side chapels along one side contained statues of St Francis and associated saints, since this church was run by Franciscans (Figure 8.2). Architects would often design spaces in anticipation of an accumulation of statues: at St Paschal Baylon in Liverpool, architect Sydney Bolland incorporated shelved niches for statues framed from the nave with plain columns, and designed bare panels above each column to receive the Stations of the Cross, all acquired later rather than designed for the church. Church buildings were populated with familiar figures that supplemented worshippers’ experience of divine transcendence with more accessible intercessors with God.

The Church often intervened to approve, moderate or condemn popular devotional practices.6 The arrangement of images in the church was also a method of constraining the laity’s enthusiastic devotions within an authorised and co-ordinated space. Nevertheless clergy and dioceses in Britain were often active in promoting non-liturgical devotions. Many devotional events took place in and around church buildings built by clergy specifically to accommodate them and formed an important part of the architect’s brief.

EUCHARISTIC DEVOTIONS

Despite the liturgical movement’s emphasis on the sacramental action of the Eucharist, the Vatican also affirmed the importance of non-liturgical devotion to the Blessed Sacrament in the tabernacle, maintaining its significance even after the Second Vatican Council. The ‘Instruction on the Worship of the Eucharistic Mystery’ advised that ‘devotion, both private and public, toward the sacrament of the altar even outside Mass … is strongly advocated by the Church, since the eucharistic sacrifice is the source and summit of the whole Christian life’.7 Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, its display outside the tabernacle in a monstrance for public veneration, was encouraged, provided it was separate from the Mass, which now could not take place with the sacrament exposed.8 For Catholics in Britain, devotion to the reserved sacrament was one of the most important activities outside the Mass and required specific architectural forms. It was also a characteristic aspect of Catholicism in relation to other denominations, contributing to a Catholic sense of identity. Bishop Beck warned that liturgical developments should not weaken devotion to the sacrament: ‘The frequent reception of Holy Communion, as well as public and private visits to the Blessed Sacrament, form part of the Catholic way of life’, he wrote, cautioning architects against excluding this important custom.9

One form of this devotion was private prayer in view of the tabernacle. The view was important: as David Morgan observes, devotional images are used for their effects of concentrating the mind and stimulating profound internal engagement with their object.10 The tabernacle with its veil and lamp was such a focal point for meditation, a recognisable sign of the ‘real presence’ of God within the church. Prayers could be said anywhere, but in front of the tabernacle they had a focused character, and the sense of divine presence was more keenly felt. Catholics who passed a church would doff a hat or make the sign of the cross, but would also feel an urge to enter, to ‘visit’ the Blessed Sacrament.

Devotion to the Blessed Sacrament could be an argument for having a church in the first place. The liturgy did not require a church – it could take place in a room in a house or a rented hall; reservation of the Blessed Sacrament, however, did require a dedicated space. At the new parish of the Holy Family at Pontefract in Leeds, parish priest John Hudson began by saying Mass in a school, but urged Bishop Dwyer to allow him to build a church, hoping not to have to begin with a temporary church hall:

A Church-Hall never seems to be regarded as more than a glorified Mass-Centre, and it seems almost impossible to prevail upon parishioners to pay visits to the Blessed Sacrament etc. For the sake of all the Catholics in the Parish, but especially the children, I feel that a Church is a necessity.11

Hudson’s wish was soon granted, and one of the most striking modern churches of the diocese opened in 1964, designed by Derek Walker with liturgical movement principles in mind. On the opening of the church, Dwyer was keen to emphasise its primary function of accommodating the liturgy, but he also acknowledged its devotional use:

The Parish of the Holy Family is rightly delighted that a permanent home for Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament is now in its midst. … We have the great privilege of His abiding presence in the tabernacle. Make it your practice to visit the Blessed Sacrament as often as you can.12

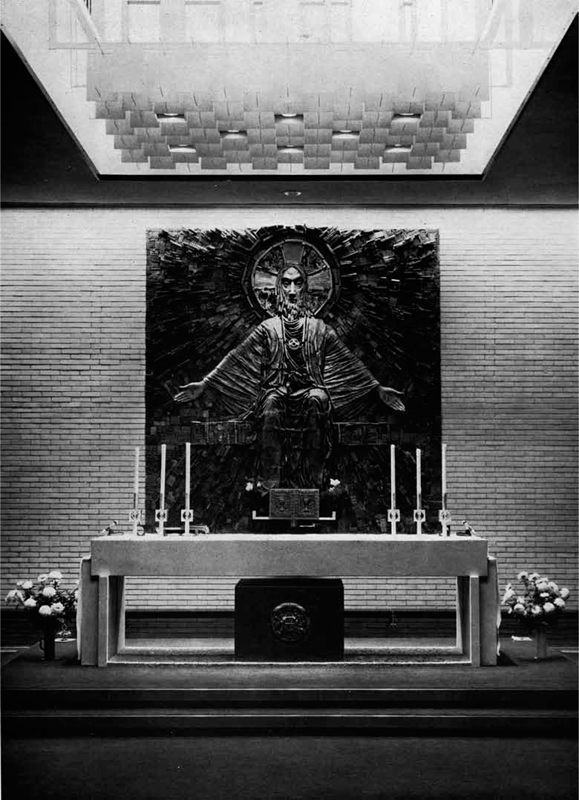

With the altar set forward for Mass facing the people, the tabernacle was set into the reredos, but it remained a strong visual feature of the interior, set at the foot of Robert Brumby’s ceramic mosaic figure of Christ in Majesty (Figure 8.3).13

Dual-purpose church halls were often designed to allow visits to the Blessed Sacrament while the building was otherwise closed or in use: in some, folding partitions across the sanctuary enclosed a permanent worship space with separate access to one side. When architect Lionel Prichard & Son presented plans for such a building in Widnes, the Archdiocese of Liverpool requested more room between altar and screen ‘to enable people to make private visits whilst the hall was in use’.14 Even when separate Blessed Sacrament chapels were planned in churches after Vatican II, devotional visits were used as justification, perhaps pre-empting criticism of any weakening of this devotion, an explanation given at St Mary, Leyland, for example.15 If it was expected that a church would be locked, the visual aspect of devotion to the sacrament could be satisfied by a glazed screen or window in an unlocked vestibule, an arrangement built into many small churches, such as that of St Pius X at New Malden by Francis Broadbent.16 Visibility could also be problematic. The parish priest of St Alexander in Bootle, a church by Velarde, removed its glazed narthex screen in 1964 and replaced it with a wall to block the view from the street when the doors were open. When questioned by the diocese, he argued that the wall ‘ensured protection and reverence for the Blessed Sacrament’, presumably from being ignored or mocked by passers-by during Mass. The diocese, however, insisted that he insert a window.17 Looking into a church and seeing the tabernacle when passing was an important custom for Catholics and one that clergy aimed to sustain.

Public forms of devotion to the Blessed Sacrament also had architectural requirements. The most common was Benediction, a service of prayers and hymns to accompany the display of the host in a monstrance. The monstrance was often placed on a temporary ‘throne’ or pedestal on or behind the altar, sometimes sheltered with a canopy. A pedestal could be built into the reredos behind the altar, a common arrangement in pre-war churches, also employed by Adrian Gilbert Scott at Sts Mary and Joseph, Poplar, where the crucifix would be removed and replaced by the monstrance, steps behind the altar giving access. Bishop Dwyer of Leeds complained that modern altars, lacking suitable structures behind them, had unworthy arrangements for exposition, and asked all parishes to ensure they at least used temporary thrones.18 Even in the late 1960s, the use of a high throne was still expected, though the hierarchy preferred it only for ‘solemn annual occasions’.19 Of these occasions the most important was Quarant’Ore, consisting of exposition for a continuous period of 40 hours with processions of the monstrance through the church, often co-ordinated across parishes so that there was continual, or at least frequent, exposition throughout each diocese.20 During this period parishes would compete in the lavishness of their ephemeral church decorations, loading altars with flowers and candles.21

8.3 Holy Family, Pontefract, Leeds, by Derek Walker, 1964. Reredos of Christ in Majesty, candlesticks, altar sculpture and tabernacle by Robert Brumby. By permission of Robert Brumby. Photo: J. Roberts & Co., 1964. Source: Leeds Diocesan Archives

In some churches, exposition was not just regular but permanent, the building accommodating this distinctive requirement. Two religious orders made permanent exposition a feature of their rule. The Blessed Sacrament Fathers arrived from branches of the order in America, settling in Liverpool, where Lionel Prichard converted a cinema into a chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, and in Leicester, where they ran the parish of the Blessed Sacrament at Braunstone and commissioned a new church from Bower Norris.22 The exterior of Norris’s Byzantine-Romanesque brick building had a ‘monastic simplicity’ suited to the order but a ‘grand scale in keeping with the noble purpose of perpetual adoration’, in the architect’s words; symbols of the monstrance on its gateposts were the only decoration. Inside there was a substantial reredos with the monstrance throne high up at the rear of the sanctuary under a framing arch.23 In London, the convent chapel of the Sisters of the Adoration Réparatrice in Chelsea served a similar function. The order came from France in 1898, and, following war damage, its new chapel of 1959 was designed in a modern, Perret-influenced style by Corfiato. The nuns occupied a screened section of the nave near the sanctuary, while the laity occupied the area behind them. An unusually tall reredos had a high platform to which the monstrance was permanently fixed so that it was visible beyond the screen and dominated the interior.24

Meanwhile every parish church celebrated one liturgical event that included formal devotion to the Blessed Sacrament: the feast of Corpus Christi, on a variable date in spring. The monstrance was carried in procession by the celebrant, attended by clergy and servers and followed by the congregation. In many parishes, such processions took place around the grounds of the church or in the streets immediately outside, and so sufficient outdoor space around the building was needed. By the 1950s, public processions reached a peak of enthusiasm and parishes would combine for processions of the Blessed Sacrament through their towns. An article in the Catholic Herald in 1951 contrasted the processions of 20,000 people in Middlesbrough, the streets lined with onlookers, with the equally zealous procession of a hundred faithful through the streets of the rural town of Machynlleth.25 Processions would pause at makeshift altars decorated to receive the monstrance; hymns were sung and Benediction given, often at civic landmarks and private houses.26 The feast of Corpus Christi was not just a popular devotion but a liturgical one following Sunday Mass, instituted by the Vatican and especially promoted at the Counter Reformation, cultivated by the clergy in Britain and fervently celebrated by the faithful.

Despite the perception of a decline in devotion to the Blessed Sacrament after the Second Vatican Council, it continued to thrive throughout the 1960s with the support of the hierarchy: Cardinal Heenan, writing in 1966, urged Catholics not to abandon devotions as a consequence of the liturgical revival, though the urgency of his appeal suggests they were already beginning to wane.27

MARIAN DEVOTIONS

The next most important and frequent devotion was to the Virgin Mary. If a Catholic church had only one shrine or statue outside the sanctuary, it would invariably be dedicated to the Virgin. Separate Lady chapels continued to be common into the 1960s and could be used to celebrate Mass on weekdays. They would often be used for private prayer to the Virgin, such as the recitation of the rosary, accompanied by the lighting of candles. There were many more public forms of devotion, however, with implications for architecture.

Many churches were dedicated to the Virgin Mary, using different titles – Our Lady of Lourdes and of Fatima celebrated her apparitions; Our Lady Help of Christians, Queen of Peace, Queen of Heaven, Star of the Sea, and the Immaculate Heart of Mary were associated with set devotions or prayers. Parishes often acknowledged their dedication in decorating churches. One of the most extravagant was St Mary at Failsworth in Manchester, designed by Tadeusz Lesisz of Greenhalgh & Williams and opened in 1964. Lesisz moved his firm’s church architecture away from its earlier modernism towards a Romanesque basilican style, and though designed around 1961 this church ignored the NCRG’s ideas about liturgy and architecture and the growing demand to limit the devotional aspects of churches. The artworks at Failsworth were conventional in style (though nothing was mass-produced) and depicted a cycle of Catholic beliefs about the Virgin. Dominating the interior was the mosaic reredos, designed by a young parishioner, B. Nolan, and made by an Italian mosaicist (Figure 8.4). Its image of the Virgin was based on the ‘Miraculous Medal’, worn by many Catholics as part of a Vatican-approved devotion following the visions of a nineteenth-century French nun, St Catherine Labouré. Over the church’s mosaic figure, angels holding a crown indicated the Coronation of the Virgin as Queen of Heaven, recently accepted into Catholic doctrine by Pius XII. This figure dwarfed every other element of the sanctuary, even dominating a frieze of Eucharistic symbols: liturgy was effectively made secondary to the presentation of Marian devotion.

Similar images were scattered throughout the church. Hanging in the entrance arch was a figure of the Virgin in aluminium by E. & J. Blackwell to Lesisz’s design depicting the Immaculate Conception – the doctrine of the Virgin’s freedom from original sin declared by Pius IX in 1854, a subject of St Catherine’s visions and, it was believed, further confirmed by the apparitions at Lourdes. The figure at Failsworth evoked the Lourdes apparitions, the church’s surrounding arch recalling the famous grotto (Figure 8.5). In a stone frieze above the windows, also by Blackwell, were depictions of the rosary meditations, suggesting that parishioners might have gathered to recite its prayers in procession around the church. Inside, the Lady chapel contained a statue described as a vision of St Catherine of Mary as Queen of the Universe, while stained-glass windows depicted further Marian attributes. The west window, finally, had been rescued and adapted from the demolished Victorian church and showed the Assumption, the ascension of Mary into heaven, also established as doctrine by Pius XII. Other devotional images were also present: a side chapel to the Sacred Heart containing a reredos from the Victorian church; a chapel to Saint Anthony; the Stations of the Cross.28 The parish of Failsworth conceived of its church as a devotional shrine, its architecture organising and framing a coherent iconography.29

Even when the liturgical movement was accepted, Marian devotions could still be cultivated as one aspect of a participatory parish culture. Gerard Goalen’s plan for Our Lady of Fatima at Harlow, for example, may have aimed at a congregational focus on the central altar, but his elevations were intended as a field for devotional imagery. Charles Norris’s dalle de verre windows illustrated the apparitions at Fatima in the nave and progressed to the rosary scenes in the transepts (Plate 12).30 The parish priest, Francis Burgess, was a member of the order of the Canons Regular of Mary Immaculate and encouraged Marian devotions at Harlow. These revolved around two statues of Our Lady of Fatima, circulated between parishioners’ houses where they would become the focus for family prayers including the recitation of the rosary, strongly advocated by Pius XII.31 The church building was undoubtedly also used for such devotional activities, and its stained glass embodied this parish community’s cultivation of devotion, especially through the prayers of the rosary. Liturgy and devotion were not so much in tension as complementary to each other in the religious practices of the faithful.

8.4 St Mary, Failsworth, Manchester, by Greenhalgh & Williams, 1961–64. Reredos mosaic of Our Lady of All Graces designed by B. Nolan. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2012

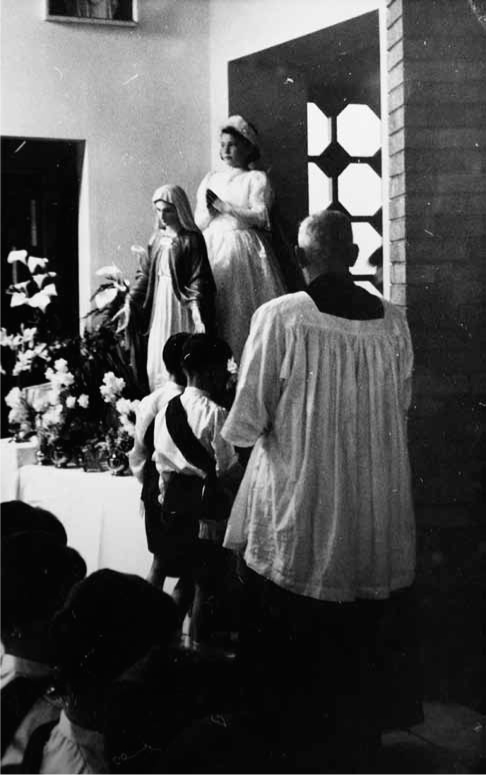

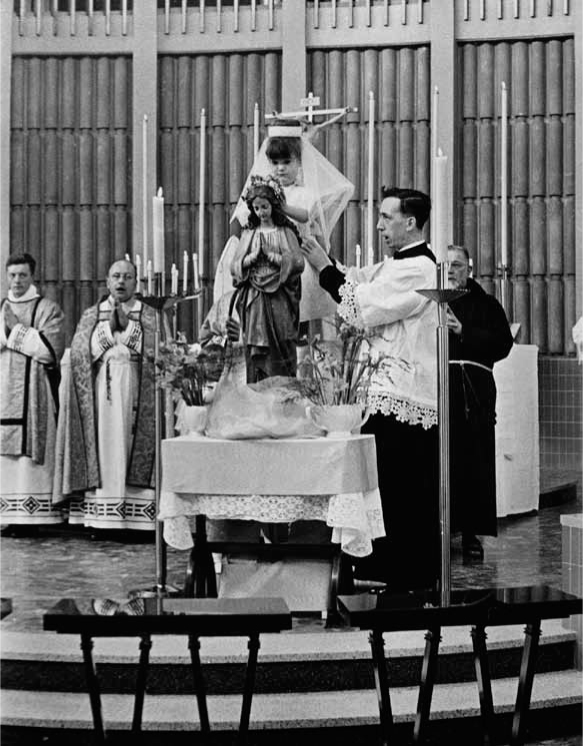

Many parishes in Britain held annual May processions at least until the end of the 1960s, usually in the grounds of the church and sometimes in the streets around it. The May devotions were a Catholic variant of a custom in many British towns of crowning a local girl as the May Queen and holding a procession: Catholics instead channelled this form into a devotional event. The May Queen, chosen from a parish’s schoolchildren, led a procession to place a crown of flowers on the statue of the Virgin brought out from the Lady chapel for the occasion. A temporary shrine decorated with flowers would be made, sometimes outdoors, sometimes inside the church: at St Stephen, Droylsden, for example, the statue was taken from its chapel and placed in front of the opening (Figure 8.6). In some places these events even took place in the sanctuary: ‘There is not much edification nor encouragement to piety and reverence, to see May Queens and retinue strutting about the High Altar to the accompaniment of clicking cameras and craning necks’, wrote one correspondent to a Catholic newspaper; yet it remained a popular practice, approved by parish priests (Figure 8.7).32 With such events in mind, Catholic churches were designed with prominent chapels for the statue of the Virgin and ample external space.

8.5 St Mary, Failsworth, Manchester, by Greenhalgh & Williams, 1961–64. External sculpture of the Immaculate Conception and Mysteries of the Rosary by E. & J. Blackwell. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2012

8.6 St Stephen, Droylsden, Manchester, by Greenhalgh & Williams, 1958–59. May devotions, 1960s. Photographer unknown. Source: parish archive. Courtesy of the Diocese of Salford

An important feature of Marian devotion was the pilgrimage to a shrine associated with her apparitions. Pilgrimages to Lourdes featured strongly in post-war Catholic life in Britain thanks to an ever-increasing ease of travel. Devotion to St Bernadette and the Lourdes apparitions also entered British churches. Many were dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes, St Bernadette or the Immaculate Conception, the doctrine that resulted from the apparitions, and many more churches had images and shrines associated with this devotion. Sometimes such shrines were built outside the church, and some were extravagant facsimiles of the famous grotto. This practice had persisted since the nineteenth century: the imitation grotto imaginatively transported its viewers to the original shrine, arousing the devotional fervour of pilgrimage in the more limited confines of the parish.33 Occasionally replica grottoes became pilgrimage sites in their own right: at Carfin in Lanarkshire, parish priest Thomas Taylor had founded such a shrine in the 1920s that, with inventive plumbing, even possessed the original’s sacred spring, becoming a national centre of pilgrimage in Scotland. A new circular church was built for it by Charles Gray, opened in 1973, though crowded ceremonies were normally conducted in the open air.34 The church of St Bernadette in Lancaster by Tom Mellor contained plentiful open ground intended from the start to be used for devotions. A Lourdes grotto was created under Mellor’s concrete campanile by Preston architect Wilfrid Mangan in 1965, several years after the church’s opening, though it had been intended originally: the architect’s perspective showed an arched opening in the tower’s basement and a pool of water in front of it; above the grotto was an open section in the campanile intended as a pulpit (Figure 8.8).35 Mangan’s plans included a paved ‘amphitheatre’ intended to accommodate crowds of visitors for ceremonies under the tower.36

8.7 St Catherine of Siena, Birmingham, by Harrison & Cox, 1961–65. May devotions, 1960s. Photographer unknown. Source: parish archive. Courtesy of the Birmingham Roman Catholic Diocesan Trustees

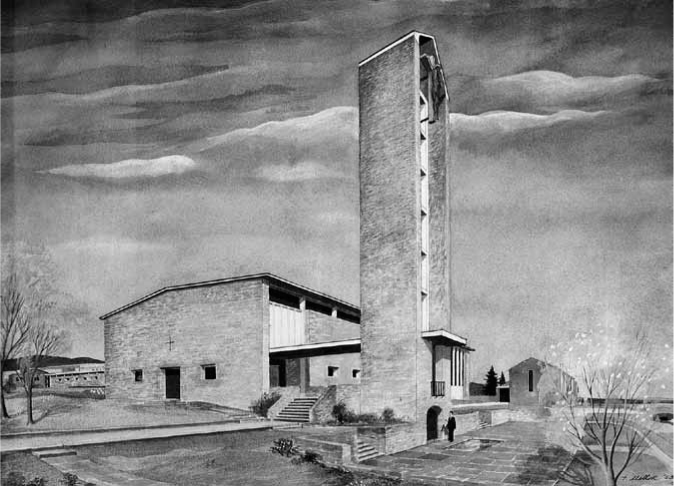

8.8 St Bernadette, Lancaster, by Tom Mellor, 1958. Perspective by the architect dated 1955. Courtesy of David Mellor. Source: parish archive

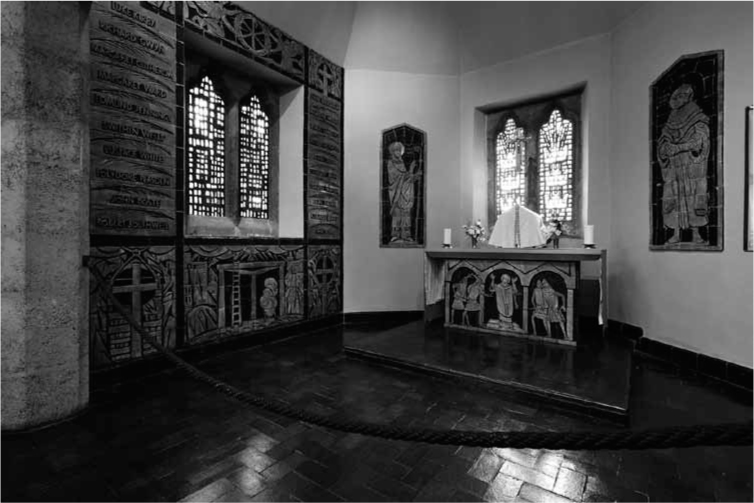

The diocese of Lancaster was in fact dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes, and, in thanksgiving for having escaped serious bomb damage in the Second World War, its bishop, Thomas Flynn, commissioned a shrine, the votive chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes in Blackpool, designed by Velarde and completed in 1957 (Plate 13, Figure 8.9). The cost was raised from the contributions of parishes across the diocese. It had little real function, not serving as a parish church: it was located near a hospital, where it might have catered for nurses or visitors, and may have been intended as a gathering point for pilgrims to Lourdes, including hospital patients, departing from Blackpool airport.37 It soon became associated with a convent of the Adoration Réparatrice. Enriched with integral carving by David John, it was a small, elaborate building, a dazzling display of gold mosaic and deep colours framing John’s understated figure of the Lourdes apparition over the reredos. Its main purpose seems to have been simply to exist as a continuous act of devotion in its own right by all the Catholics of the diocese.

STATIONS OF THE CROSS

The Stations of the Cross were another important devotion with a prominent place in nearly every Catholic church in Britain. Like Marian devotions, the Stations hinged around visual cues provided by images, and architects often considered them an important function in church design. The Stations, formalised by the Church in the eighteenth century, consisted of a series of prayers and meditations with ritual actions including genuflection at 14 episodes in the Passion of Christ, beginning with the condemnation of Christ by Pilate and culminating in the entombment. Some episodes were drawn from the Bible and others were traditional, such as the miraculous imprint of Christ’s face on Veronica’s veil. Regulations attached to the devotion established rules for its minimum form, prescribing a series of prayers made in procession past wooden crosses attached to the church’s walls. Images were not formally required, but were normally hung alongside the crosses, and often included the crosses in their frames. A physical procession was theoretically required, but if necessary the congregation could remain in the pews, turning to watch the priest and servers as they moved.38 The devotion was practised regularly as a public ceremony and also privately, especially in Lent. The rules set by the Church for this ritual were established in connection with the indulgence it granted and were carefully followed, the Clergy Review often advising priests on the correct forms of the devotion.39

8.9 Votive Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes, Blackpool, by F. X. Velarde, 1955–57. Integral sculpture by David John. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2011

Though never required in a church, the Stations were nearly always present. The competition brief for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral stated that the 14 positions for the Stations had to be marked on competition plans, and when competitor Clive Entwistle asked whether these were obligatory the answer was affirmative and that they must be placed in the nave.40 Gibberd’s design had 16 slim structural supports surrounding the nave, and when in 1964 the cathedral committee came to consider the Stations there was some debate. One member thought they were ‘not a necessary part of the furnishing of a church or cathedral, but concerned rather with private devotions’, and that as there was already a set in the crypt the cathedral did not need another. Gibberd suggested that plain crosses might be placed in the nave, but, the committee agreed, ‘it was felt that this would not be popular with the people’. The faithful expected images, and, though the clergy were sympathetic, they deferred a decision indefinitely.41 This was an unusual situation, however, and even those writers who followed the liturgical movement generally thought this devotion should have a significant place in the church. Crichton’s ‘Dream Church’, for example, envisaged the Stations as a painted frieze in a circular aisle wide enough for a full procession.42

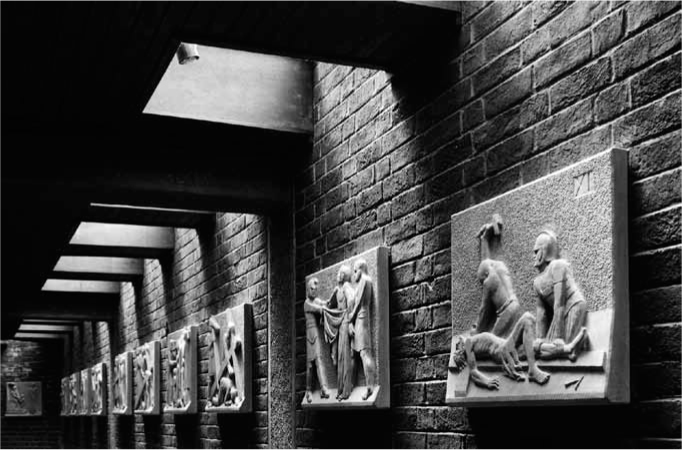

As a popular, non-liturgical devotion, it was important to clergy that the Stations of the Cross should contain images that ordinary parishioners could use as devotional aids, and so the events of the Passion had to take a recognisable form, inspiring meditation on the sufferings of Christ. In Edinburgh, for example, Archbishop Gray assiduously solicited opinions from clergy and laity on abstract designs by Fred Carson for Stations at the new church of St Gabriel at Prestonpans, concluding that the artist’s work ‘may indeed be the artistic pattern for the future, but if so we are not yet prepared for it’ and refusing to endorse the commission, and though what must have been a revised design did eventually proceed, an abstract treatment remained unusual.43 Eric Gill’s Stations at Westminster Cathedral were the most important precedent for artists commissioned by modern architects for stone panels: hieratic figures were thought capable of expressing strong emotions without sentimentality to assist the viewer in meditation.44 At Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow, for example, Irene Foord-Kelcey’s Stations of the Cross were, like Gill’s, in Hopwood stone and boldly primitive in style, described in emotional terms: her interpretation of the narrative was an unfolding of ‘the entire tragedy, Love, Agony, and Death’; the women of Jerusalem demonstrated their ‘utter desolation’, as ‘each figure seems obsessed by grief’ (Figure 8.10).45 Even as late as 1970, a modern church could receive Stations loosely inspired by those of Gill: at John Rochford’s church of St Paul at Wood Green in London, the commission was given to Michael Clark, who had stayed at Gill’s community at Ditchling. His stone reliefs were less stylised than Gill’s but hardly more realist: their figures were taut with unreleased emotive energy, drenched in white raking light from above the processional strip of space that Rochford had designed for them (Figure 8.11).

Such an approach – the stone plaque embedded in or attached to the wall – was only loosely integrated with architecture, and many modern architects tried to incorporate this devotional function more rigorously into their designs. At their church of St Martin at Castlemilk in Glasgow, MacMillan and Metzstein of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia made the Stations an articulating element (Figure 8.12). Windows in the side walls of this church were combined with the Stations. Plaster casts of typical church furnishers’ images were cut down and inserted into the 14 splayed embrasures. The pious images therefore satisfied conventional devotional desires, but, in their almost ghost-like presence, must have been intended by the architects as more like quotations of the kitsch, an ‘as-found’ element brought into the architecture in the manner of the Independent Group. Though integrated, however, these panels revealed themselves to be superfluous, since the wooden crosses that constituted the canonical form were separate, attached to the window sills and silhouetted against the coloured glass. These unconventional Stations gave ritual meaning to the architecture of the nave walls as a strong visual feature of the church’s interior while creatively exploring the implications of the ritual’s rules.

8.10 Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow New Town, by Gerard Goalen, 1954–60. Stations of the Cross by Irene Foord-Kelcey. By permission of Christopher Foord-Kelcey. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

8.11 St Paul, Wood Green, London, by John Rochford, 1967–72. Stations of the Cross by Michael Clark. By permission of Joseph Lindsey-Clark. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

8.12 St Martin, Castlemilk, Glasgow, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1957–61. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

Other architects incorporated Stations more literally into the windows. At Weightman & Bullen’s Holy Ghost at Bootle in Liverpool, opened in 1958, Joseph Nuttgens made the Stations in stained glass, lit from outside when used after dark.46 Stained glass was normally associated with a decorative rather than devotional purpose; here, however, architect and craftsman gave the stained-glass window a new functional role in the church building. Reynolds & Scott later did the same at Christ Church, Heald Green; Peter Langtry-Langton incorporated more modern stained glass Stations at St Joseph, Hunslet, and Gillespie, Kidd & Coia employed Sadie McLellan for this purpose at the Sacred Heart in Cumbernauld (Figure 7.13). At the English Martyrs, Horley, architect Justin Alleyn commissioned stained-glass Stations that were especially clearly related to the church’s plan. Fourteen slot-shaped windows articulated a processional circuit around the octagonal nave, with expressive modern versions of the scenes in dalle de verre by Fourmaintraux, also lit from outside (Plate 14).47

Linear friezes of Stations were perhaps easiest to integrate into the church’s design: at St Aidan at Acton, two horizontal slots in the side aisles were filled with blue and gold mosaic, a background for figures by Arthur Fleischmann.48 More dramatic was F. R. Bates, Son & Price’s church of St Francis of Assisi in Cardiff. Adam Kossowski made several sets of Stations for churches across England and Wales in glazed ceramics, but at St Francis he went much further. Instead of hanging work on walls, he was given a curved balcony frontage in an arc around the church and used it to give the scenes a setting and an effect of movement (Plate 15). A backdrop of green sgraffito depicted buildings and hills and his ceramic pieces were placed over the top, the pink cross making a rhythmic motif across the frieze. A passageway between pews gave a processional route sufficient for priest and servers to pass under the Stations in sequence, the images visible to the worshippers from their seats. It was an innovative work that dominated this small modern church, articulating its space.

The Second Vatican Council prompted a significant shift in ideas about devotions, centring on the practice of indulgences. Devotions before the Second Vatican Council were highly motivated by indulgences, attached by the Church to set prayers and actions: the indulgence would be phrased as an equivalent number of days or months of fasting, or would be ‘plenary’, fully preparing the subject for heaven. A ritual stance towards devotions was encouraged because indulgences only applied when the actions or prayers to which they were attached were performed correctly, and so indulgences also helped to regulate popular devotion.49 Reformers, however, worried that the faithful treated such devotions as magical acts rather than genuine prayer capable of bringing the individual closer to God.50 Consequently Paul VI announced in 1967 that indulgences were to be reduced and simplified and loosened from their connections to specific objects or places.51 This reform aimed to change the emphasis in devotions from public ritual actions towards personal, thoughtful piety.

The Stations of the Cross were revised the following year. The devotion still attracted a plenary indulgence, but its rules were relaxed: 14 Stations were required, but their visual forms were undefined; a processional movement was still required, but the prayers did not have to relate to the conventional episodes and could instead be a general meditation on the Passion. These changes increased the latitude for creativity in the design of the Stations, a freedom made use of at Clifton Cathedral. Here, the architects wanted the Stations to be integral to the architecture and commissioned William Mitchell, a well-established architectural sculptor who had recently made the doors and bell tower at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Mitchell had previously refused a commission for Stations for the seminary chapel at Kirkby Lonsdale in Lancashire, doubtful of their contemporary relevance. When he presented his ideas and sketches to the clergy at Clifton in 1972, they constituted such a departure from the norm that they were sent for approval to Annibale Bugnini, Secretary of the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship at the Vatican.52 Mitchell’s new series omitted all but one non-scriptural event, added the Last Supper to the beginning of the sequence and the Resurrection to the end, and included Christ’s forgiving of the repentant sinner on the cross.53 This revised sequence made significant changes to the focus of this devotion, away from the suffering of Christ and towards the more general significance of the Passion and Resurrection. Mitchell conceived of his new series as more relevant for the modern world: the agony in the garden, for example, represented contemporary conditions of stress and anxiety.54

8.13 Clifton Cathedral, Bristol, by Percy Thomas Partnership, 1965–73. Stations of the Cross by William Mitchell. By permission of William Mitchell. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2013

The architects made the Stations an important feature of the interior of the new Cathedral with large panels along the processional circuit around the rear of the nave (Figure 8.13). Mitchell’s technique incorporated them literally into the fabric of the architecture: the building’s walls were of a fine board-marked concrete, and the Stations were made with a fast-setting cement called ‘Faircrete’ into which the designs were rapidly drawn. The immediacy of the technique, Mitchell thought, would prevent conventional forms from creeping into his work.55 The figures were bold and primitive, heads, hands and clear symbols in low relief. Their placement in the cathedral gave them a distinct relationship with the liturgy, reflecting the primary concern of clergy and architects at Clifton and the liturgical movement aim of making devotions more liturgical. Since the revised sequence began with the Last Supper it already contained a liturgical allusion; the Resurrection scene, moreover, depicted Christ’s hands breaking bread in reference to his appearance at Emmaus. Clifton’s Stations of the Cross therefore began and ended with Eucharistic motifs, suggesting an understanding of the Passion in relation to liturgy and making this devotion more relevant to the principal purpose of the church building. With newly written prayers and images that were unfamiliar to the faithful, Clifton’s Stations were designed to rouse worshippers out of ritual habits to force them to think in a new way about this devotion, even as its customary prominence in the church was maintained.

PILGRIMAGE

In comparison with the sobriety and ubiquity of the Stations of the Cross, the custom of pilgrimage was entirely different, attended with festivity and focused on unique, special places. Though pilgrimages have often been attributed to the laity as spontaneous responses to miraculous events, post-war British pilgrimages were organised by the clergy and deliberately invented – or reinvented – to stimulate the devotion of the faithful. Architects and artists participated in this invention, providing spaces with a heightened sense of the sacred as frames for pilgrimage activity. Victor Turner’s anthropological theory of pilgrimage describes it as a rite of passage, occupying a liminal place imbued with qualities associated with sacredness where pilgrims can briefly subvert authorised rules of conduct in an atmosphere of fellowship, or communitas: though he also notes that religious authorities often intervene to regulate it and subdue any excesses.56 Pilgrimage shrines offered the promise of special contact with the sacred and personal transformation, prompted by a surfeit of symbolic objects, images and activities.57 Moreover, Turner sees a resurgence in pilgrimage in the twentieth century as a popular reaction against modernising and iconoclastic tendencies in the Church.58 More recently Robert Maniura has noted the highly variable and flexible nature of pilgrimage devotions: ‘pilgrimage has no rubric’, he writes, and many kinds of actions and experiences may be available at a shrine.59 As with other devotions, the central principle of pilgrimage is vision: ‘the people come “to see the image”’ – a principle certainly maintained in the revived pilgrimages of post-war Britain.60

A significant concern of British Catholics was that the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII and the subsequent Protestant Reformation had obliterated all historical pilgrimage shrines. Even when the buildings and sites of shrines remained in the care of other denominations, nearly all devotional features, including the bodies of saints, were lost. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the absence of the relics and shrines of the saints was keenly felt and nostalgically evoked in new churches. For Catholics the landscapes of England, Scotland and Wales were marked by sites of loss, inspiring efforts to revive and restore the ancient shrines and their pilgrimages. Among them, two post-war examples stand out as particularly important: the shrine of St Simon Stock at Aylesford Priory in Kent, and that of Our Lady of the Taper at Cardigan in Wales.

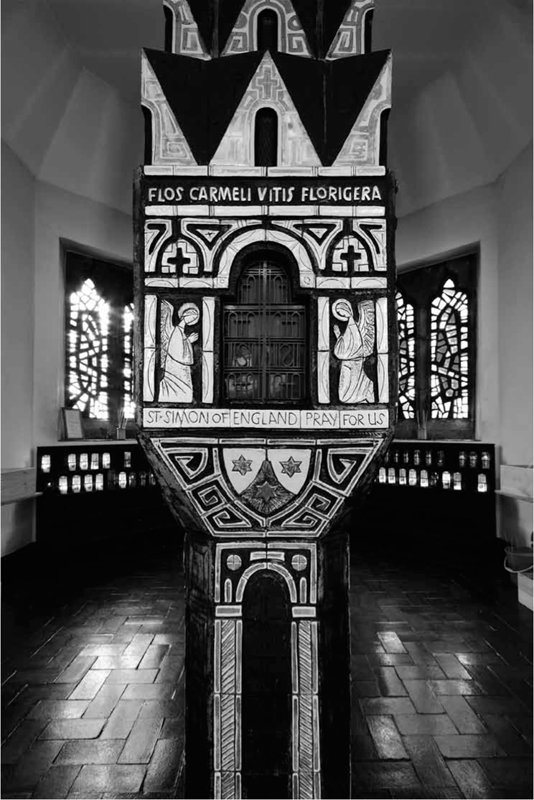

Aylesford Priory, near the pilgrim route to Canterbury, was a Carmelite foundation established in the thirteenth century and handed over to secular use with the dissolution of the monasteries, its fifteenth-century church subsequently demolished.61 One of its earliest abbots had been St Simon Stock, reputedly witness to a vision of the Virgin Mary that inspired a devotion known as the ‘scapular’. This was a brown cloth, later reduced to a small piece of cloth bearing an image of the Virgin, whose wearers were assured an indulgence, a devotion that became almost as popular as the rosary.62 The Carmelite order reestablished itself in Britain in 1949 when a group of Irish monks purchased the remaining cloistered cottages at Aylesford, arriving with a dignified procession.63 Two years later they were given a relic of the skull of St Simon Stock by the cathedral of Bordeaux. The transfer of the relics, hailed as a ‘homecoming’ of the saint by the Catholic press, was accompanied by ceremonies that attracted over 20,000 visitors.64 The priory soon became a major pilgrimage site through the enthusiastic publicity of the prior, Malachy Lynch, and a few years later Adrian Gilbert Scott was appointed as architect to build a new chapel and accompanying shrines to transform it into a worthy pilgrimage centre. Lynch also set about creating a hub of Catholic artistic and craft activity along the lines of Gill’s colony at Ditchling, and attracted Kossowski to contribute his most important body of work to extend and complete the buildings.65

The romantic liminal setting of the priory was an attraction to pilgrims: though the town of Aylesford was easy to reach from London, visitors had to cross a bridge over the Medway river and climb a hill to its concealed site, a journey evoked in spiritual terms in journalistic reports.66 The site’s qualities of loss, ruination and recovery were also powerful, as the ruins of the medieval church were discovered on the site and many of its stones used for new buildings when work began in 1954.67 Adrian Gilbert Scott’s design for a new church did not, however, attempt to replicate the old: instead it preserved the sense of loss by placing a sanctuary under a broad tower and leaving the nave open to the sky (Figure 8.14). The open-air gathering had become a feature of pilgrimage experience in Britain since medieval churches were not available for Catholic use, and it was consciously retained at Aylesford. The building consisted of a complex series of chapels distributed along cloistered walkways framing the open-air nave. It was a network of interconnected shrines, its elevations forming a self-effacing backdrop for a profusion of devotional imagery. The chapels were decorated with vivid ceramics and sgraffito by Kossowski, who also made many of the liturgical furnishings, and Charles Norris contributed dalle de verre windows (Figure 8.15). One chapel was dedicated to Carmelite saints, another to the English Reformation martyrs; there was a chapel to St Anne, the mother of Mary; and behind the sanctuary was the shrine to Simon Stock containing Kossowski’s towering reliquary, installed in 1964 (Figure 8.16). Michael Clark was commissioned for a figure of the Virgin of the Assumption, ceremonially installed over the high altar against a glittering ceramic backdrop by Kossowski.68 There was a ‘rosary way’, Kossowski’s earliest work at Aylesford, a series of majolica plaques around a garden behind the shrine. Pilgrims visiting Aylesford would undertake the primary ceremonies of Mass and Benediction in the open nave, but multiple dispersed and secondary devotional activities were available too: visits and prayers at the reliquary and other chapels; the Stations of the Cross; and recitation of the rosary in an imaginative and romantic setting. It was an encapsulation and intensification in one evocative site of all the main devotional activities of Roman Catholicism.

The site became a pilgrimage centre, ‘the foremost shrine of Our Lady in England’, with the co-operation of the hierarchy.69 Bishop Cowderoy of Southwark led frequent ceremonies attended by thousands. When the relic was installed, he celebrated Mass in the presence of the bishop of Bordeaux and a representative of the Vatican.70 Cowderoy declared in a sermon that he ‘could never be tired … of encouraging by every means in his power this great work destined to play a great part in the bringing of this land back to be Our Lady’s Dowry’, and the Vatican granted a plenary indulgence for pilgrims at his request.71 Lynch, meanwhile, was adept at publicity and fundraising, attracting volunteer donors and builders through ‘Our Lady’s Building Company’, whose 25,000 members received a newsletter and reports of miraculous events.72 It was an orchestrated plan to capture the imaginations and harness the devotional desires of British Catholics.

8.14 Aylesford Priory, Kent, by Adrian Gilbert Scott, 1954–64. Central sculpture of the Virgin Mary by Michael Clark. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

8.15 Aylesford Priory, Kent, by Adrian Gilbert Scott, 1954–64. Chapel of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales: ceramics by Adam Kossowski; dalle de verre windows by Charles Norris. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

8.16 Aylesford Priory, Kent, by Adrian Gilbert Scott, 1954–64. Reliquary of St Simon Stock by Adam Kossowski; dalle de verre windows by Charles Norris. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

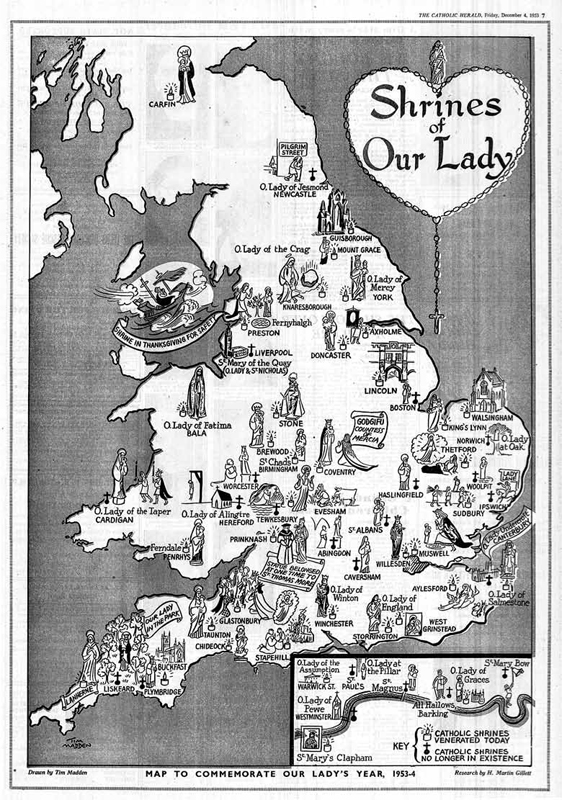

Pilgrimages in Britain continued to grow after the Second Vatican Council. At Our Lady of the Taper in Cardigan a church was built after the council that reconciled devotional practices to liturgical ceremonies in a manner informed by the liturgical movement. This shrine was also newly ‘restored’ after the Second World War. In December 1953, on the eve of a ‘Marian year’ announced by Pius XII, Cardigan appeared on a pictorial map in the Catholic Herald showing the modern and medieval Marian shrines of England, Wales and the south of Scotland made by Catholic historian Martin Gillett and illustrator Tim Madden, later also issued as a poster (Figure 8.17).73 This striking image interpreted Britain as a lost landscape of Marian devotion, complete with iconic statues and miraculous apparitions. The former medieval shrine of Our Lady of Cardigan, the subject of a recent booklet by a local historian, was prominently marked. Gillett and the parish priest of Cardigan, George Anwyll, persuaded the bishop of Menevia, John Petit, to revive the shrine.74

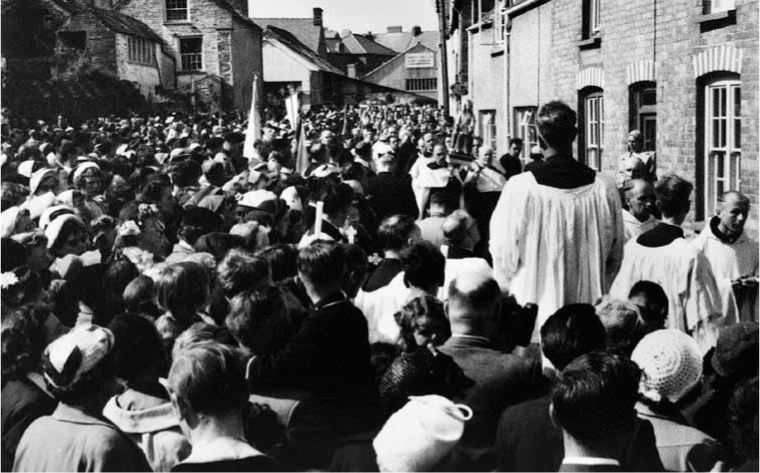

Gillett became involved in its establishment at the bishop’s request: he had named it ‘Our Lady of the Taper’, as its medieval statue was thought to have held a candle, and he oversaw the creation of a statue by Benedictine sculptor Vincent Dapré. The new statue was blessed by Cardinal Griffin in Westminster Cathedral in 1956 and toured the diocese of Menevia before arriving in procession at Cardigan, where it was solemnly installed by Petit in the tiny parish church (Figure 8.18).75 Seamus Cunnane succeeded Anwyll as parish priest in 1962 and assiduously promoted the shrine as a pilgrimage centre, campaigning for a new church capable of accommodating pilgrims and ceremonies. Nevertheless Cunnane thought that the small size of the existing parish church was not a hindrance to the pilgrimage: rather than bringing the statue into an open space, he wanted pilgrims to overflow from the church and to enter later for private devotion, considering the experience of visiting a shrine an important feature of pilgrimage.76 When a new church eventually became possible, he retained this idea in its design.

The old church was not only too small but was also threatened with demolition to make way for a road, so a new site and building were necessary.77 Petit wanted to acquire Cardigan’s medieval castle, perhaps to recreate a medieval pilgrimage atmosphere and lend historical authority to the restoration of this devotion, but Cunnane instead found a site with room to expand and open grounds for gatherings of the faithful in a more suburban location.78 Cunnane closely directed the architect, Merrick Sloan of Weightman & Bullen, in the new church’s design, considering how pilgrimage activities would take place in and around the building. The statue shrine, a glazed tower with room for only a few people, was separate from the church, linked to it by a wall surrounding a courtyard from where it could be viewed by the assembled crowds (Figure 8.19). The shrine kept this devotional activity apart from liturgical events so that congregations attending Mass would not be distracted by devotions. The timber-framed church was relatively small for parish use, but for large gatherings of pilgrims the faithful could stand in the open courtyard, glazing at the rear of the nave allowing them to see inside. Cunnane and his architects embraced the Catholic pilgrimage culture of outdoor settings and the sense of fellowship given by a dense crowd, combining this occasional devotional function with the building’s more regular liturgical use. The opening and consecration ceremony for the church in 1970 demonstrated its pilgrimage functions. A procession through the town brought the statue from the old church to the new shrine, and its taper was lit by Gillett in front of the crowds in the courtyard.79 The church of Our Lady of the Taper demonstrates the enormous and continuing popularity of Marian pilgrimage devotion in post-war Britain even after the Second Vatican Council: modern in style and architectural approach and purpose-built to contain popular devotions in carefully considered relationship to the liturgy, the church sustained the popular religious enthusiasm of Catholics in post-war Britain in accordance with the tenets of the council.

8.17 ‘Shrines of Our Lady’, from Catholic Herald (4 Dec. 1953), 7. Drawn by Tim Madden. Courtesy of the Catholic Herald, catholicherald.co.uk

8.18 Pilgrimage of Our Lady of the Taper, Cardigan. Undated photograph, appearing to show installation of new statue in 1956. Photographer unknown. Source: Menevia Diocesan Archives. Courtesy of the Diocese of Menevia and Canon Seamus Cunnane

8.19 Our Lady of the Taper, Cardigan, by Weightman & Bullen, 1970. View from courtyard: statue-shrine to the left; church in the centre; presbytery forming wall to the right. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

NOTES

1 Guardini, Spirit of the Liturgy, 18, 56, 60–61.

2 ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’, in Abbott (ed.), The Documents of Vatican II, 175.

3 Crichton, ‘Art at the Service of the Liturgy’, 170.

4 Margaret Hebblethwaite, ‘Devotion’, in Hastings (ed.), Modern Catholicism, 240–41.

5 Kenneth Allan, ‘Obviously Post-Vatican II’, Catholic Herald (3 Mar. 1967), 6; ‘The Good Church Guide: St Aidan’s, Coulsdon’, Clergy Review 58 (1974), 552–4.

6 See Robert Anthony Orsi, The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880–1950 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985).

7 Sacred Congregation of Rites, ‘Instruction on Worship of the Eucharistic Mystery’ (1967), art. 58. The Catholic Liturgical Library, http://www.catholicliturgy.com/index.cfm/FuseAction/DocumentContents/Index/2/SubIndex/11/DocumentIndex/338 (accessed 12 Sept. 2012).

8 Ibid., arts 60–66; cf. pre-conciliar instructions in Fortescue, The Ceremonies of the Roman Rite, 351.

9 George Andrew Beck, ‘Liturgy and Church Building’, 163.

10 David Morgan, The Sacred Gaze: Religious Visual Culture in Theory and Practice (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 50.

11 John E. Hudson (parish priest, Holy Family, Pontefract), visitation paper (12 Oct. 1958) (Leeds Diocese Archives [LDA], Parish File for Holy Family, Pontefract).

12 George Patrick Dwyer, foreword to souvenir booklet, Holy Family, Pontefract (1964) (LDA, Parish File for Holy Family).

13 See also CBRN (1964), 131–5; ‘7 New Churches’, Architectural Review (Oct. 1965), 256–8.

14 Sites and Buildings Commission (19 Nov. 1957) (LRCAA, Finance Collection, 12/S3/III).

15 CBRN (1959), 172.

16 CBRS (1956), 48–51.

17 Minutes of meetings of the Council of Administration, Archdiocese of Liverpool (13 Apr.; 6 July 1964) (LRCAA, Beck Collection, 5/S3/I).

18 George Patrick Dwyer, letter to clergy (ad clerum) (3 Apr. 1962), Acta ecclesiae Loidensis 31 (LDA).

19 ‘Statement and Directives on Devotion to the Blessed Sacrament drawn up by the Archdiocesan Liturgical Commission and Circulated to the Clergy with the Approval of the Archbishop’ (c.1968) (LRCAA, Beck Collection, 5/S3/IV); see also National Liturgical Commission of England and Wales, Pastoral Directory, 19.

20 Diocese of Salford, Almanac for 1965, 25–7 (SDA); Fortescue, The Ceremonies of the Roman Rite, 349–58.

21 For example CBRN (1956), 93.

22 CBRN (1972), 160–61; ‘U.S. Priests Coming to Leicester’, Catholic Herald (24 Aug. 1951), 5.

23 CBRS (1956), 98–9.

24 CBRS (1959), 39–42; see also ‘New Chapel on Site of Saint’s Home’, The Universe, Scottish edn (14 Nov. 1958), 9; Patricia E. C. Croot (ed.), A History of the County of Middlesex, vol. 12: Chelsea (London: Institute for Historical Research, 2004), British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=28726 (accessed 18 Oct. 2012).

25 ‘Parish of 50 Has Its Procession’, Catholic Herald (1 June 1951), 5.

26 ‘Benediction in the Market Place’, Catholic Herald (12 June 1953), 7; ‘A Moment of Reverence’, The Universe, Scottish edn (13 June 1958), 16.

27 John C. Heenan, Council and Clergy (London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1966), 90.

28 St Mary’s, Failsworth: 1845–1964 (Manchester: n.p., 1964) (parish archive); see also CBRN (1964), 77–81.

29 For a more critical view, see Walker, ‘Developments in Catholic Churchbuilding’, 382.

30 Charles Norris, ‘The Stained Glass Windows’, in Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow: Opening Souvenir Booklet (Harlow New Town: n.p., 1960), 44 (BDA, I3).

31 Elinor Moreton Smith, ‘Recent Catholic Development in Harlow’, in Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow: Opening Souvenir Booklet (Harlow New Town: n.p., 1960), 21, 27; Francis Burgess (parish priest, Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow) to Bernard Patrick Wall (bishop of Brentwood) (20 Feb. 1956); Burgess to George Andrew Beck (bishop of Brentwood) (14 July 1954) (BDA, I3).

32 Sacerdos, ‘May Queen Unsuitable Customs’, Catholic Herald (31 May 1957), 2.

33 See for example McDannell, Material Christianity, 155–62; see also Ruth Harris, Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age (London: Allen Lane, 1999), 72–84.

34 Solemn Opening of the New Church of St Francis Xavier, Carfin (Carfin: n.p., 1973) (SCA, HC/57).

35 Tom Mellor, watercolour painting (1955) (parish archive of St Bernadette, Lancaster); CBRN (1958), 135; also Aedificatio: A History of St Bernadette’s Church, Bowerham, Lancaster (n.d.), 12–14 (Lancaster Roman Catholic Diocesan Archives [LRCDA], Parish File).

36 Wilfrid C. Mangan, plan drawing (9 Aug. 1962) (parish archive, St Bernadette, Lancaster).

37 For example ‘A Prayer Fashioned in Stone’ [newspaper cutting], Blackpool Evening Gazette (13 May 1982), 12 (church archive, Our Lady of Lourdes, Blackpool); see also English Heritage, ‘Thanksgiving Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes’ (30 June 1999), http://list.english-heritage.org.uk/resultsingle.aspx?uid=1387319 (accessed 23 Oct. 2012).

38 Fortescue, The Ceremonies of the Roman Rite, 242–3.

39 J. O’Connell, ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 40 (1955), 537–40; L. L. McReavy, ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 42 (1957), 554–6; Urban Judge, ‘Erection of the Stations of the Cross’, Clergy Review 44 (1959), 682–5.

40 Architectural Competition for the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, 19; Clive Entwistle to Mgr Turner (cathedral competition secretary, Archdiocese of Liverpool) (25 Nov. 1959) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/VIII/A/12); competitors’ questions and answers (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/VIII/A/17).

41 Cathedral Executive Committee (12 Nov. 1964) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/XI/A/5).

42 Crichton, ‘A Dream-Church’, 73.

43 Gordon Gray (archbishop of Edinburgh and St Andrews) to Walter Glancy (14 May 1965) (SCA, DE/39/29).

44 Roulin, Modern Church Architecture, 34–5.

45 ‘The Stations of the Cross’, in Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow: Opening Souvenir Booklet (Harlow New Town: n.p., 1960), 58 (BDA, I3). The sculptor’s surname was often written, as here, ‘Foord-Kelsey’.

46 CBRN (1958), 42–8; attributed to Joseph Nuttgens by Paul Quail, Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen untitled draft news sheet (June 1957) (ASCA, uncatalogued).

47 CBRS (1962), 108–13.

48 CBRS (1962), 65–6.

49 On this idea, see for example McDannell, Material Christianity, 23–4; Victor Turner and Edith Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978), 193.

50 For example T. Corbishley, letter to the editor, The Tablet (27 Jan. 1962), 89; L. L. McReavy and J. B. O’Connell, ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 51 (1966), 804.

51 Paul VI, ‘Indulgentiarum doctrina’ (1967), The Holy See, http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/apost_constitutions/documents/hf_p-vi_apc_19670101_indulgentiarum-doctrina_en.html (accessed 31 Oct. 2012).

52 T. J. Hughes (vicar general, diocese of Clifton) to Annibale Bugnini (secretary of the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship, the Holy See) (12 Feb. 1972); Hughes to Bugnini (19 Oct. 1972); Bugnini to Hughes (20 Nov. 1972) (CDA, Cathedral File, ‘Way of the Cross’).

53 Typescript text of Stations of the Cross (c.1972); W. J. Mitchell (secretary to bishop of Clifton) to members of the Liturgical Commission of the Diocese of Clifton (10 Mar. 1972) (CDA, Cathedral File, ‘Way of the Cross’).

54 William Mitchell, telephone interview with Robert Proctor (23 Nov. 2012).

55 Ibid.

56 For example Victor Turner, Dramas, Fields and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press 1974), 166–230; Turner and Turner, Image and Pilgrimage, 27, 29–31.

57 V. Turner, Dramas, Fields and Metaphors, 197.

58 Ibid. 223.

59 Robert Maniura, Pilgrimage to Images in the Fifteenth Century: The Origins of the Cult of Our Lady of Częstochowa (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2004), 88.

60 Ibid. 90.

61 ‘Friaries: The Carmelite Friars of Aylesford’, in William Page (ed.), A History of the County of Kent, vol. 2 (London: Archibald Constable, 1926), 201–3, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=38223 (accessed 2 Nov. 2012).

62 Joseph Christie, ‘English Saints: St Simon Stock – A Sturdy Kentishman – England’s First Carmelite Friar’, Catholic Herald (16 May 1941), 6.

63 Douglas Hyde, ‘The Carmelites Kept Vigil at Aylesford: Home at Last’, Catholic Herald (4 Nov. 1949), 1.

64 ‘A Great New Shrine of Our Lady’, Catholic Herald (13 July 1951), 1; ‘St Simon Home in Triumph’, Catholic Herald (20 July 1951), 1.

65 Much of what follows borrows from Rosemary Hill, ‘Prior Commitment’, Crafts 172 (Sept.–Oct. 2001), 28–31; on Kossowski’s work, see Pearson, ‘Broad Visions’, 7.

66 [Michael de la Bédoyère], ‘Ancient Stones Guarded Secret’, Catholic Herald (28 Oct. 1949), 5.

67 ‘Ancient Stones are Used in New Shrine’, The Universe, Scottish edn (25 July 1958), 7.

68 ‘From Our Notebook’, The Tablet (26 Nov. 1960), 1088.

69 ‘Carmelites Come Back’, The Tablet (20 Sept. 1969), 938.

70 ‘A Great New Shrine of Our Lady’.

71 ‘Never Tired of Coming’, Catholic Herald (24 Aug. 1956), 7; ‘Inspiration to Great Courage’, Catholic Herald (4 Dec. 1953), 13.

72 Marian Curd, ‘Why Look Abroad for a Building Company?’, Catholic Herald (6 Feb. 1959), 5.

73 ‘Shrines of Our Lady’, Catholic Herald (4 Dec. 1953), 7; ‘The Map of the Year’, Catholic Herald (11 Dec. 1953), 1; Martin Gillett, ‘Our Lady’s Dowry’, letter to the editor, Catholic Herald (15 Apr. 1954), 2.

74 John A. W. Bate, ‘The Modern Story of Our Lady of the Taper’, Menevia Record (Feb. 1956), 10 (MDA).

75 Seamus Cunnane, Our Lady of Cardigan: A History and Memoir (Cardigan: n.p., 2006), 15–19; O.J.M., ‘Our Lady’s Triumphal Tour’, Menevia Record 4 (Aug. 1956), 10–12 (MDA).

76 Seamus Cunnane (parish priest, Our Lady of Sorrows, Cardigan) to John Petit (bishop of Menevia) (23 Mar. 1964), (MDA, parish file for Our Lady of the Taper, Cardigan); Seamus Cunnane, telephone interview with Robert Proctor (29 June 2012).

77 For example parish newsletter for Our Lady of Sorrows, Cardigan (28 May 1967) (MDA, parish file for Our Lady of the Taper).

78 Various correspondence (MDA, parish file for Our Lady of the Taper); Seamus Cunnane, interview with Robert Proctor (29 June 2012).

79 Cunnane, Our Lady of Cardigan, 29–31.