EMBODIED ENERGY AND THERMAL MASS

Sustainability is the careful use of resources to accomplish the fulfilment of current needs so that there will be resources remaining to accomplish the fulfilment of future needs. Easter Island is one of the most remote places on earth. It is 1,400 miles from the main part of Polynesia to the west and 2,300 miles from Chile to the east. Polynesians settled the island around 400 AD. The 64 square mile island was covered with a forest of palm trees. The population of the island grew, and the culture prospered. The Easter Islanders produced spectacular statues as part of their religious observances that they sculpted from volcanic stone and then transported the statues to sites near the water by rolling them on tree trunks. Along with other uses of the palm trees on the island, this practice eventually used up all the trees on the island. As the population exceeded resources and there were no trees to create boats and rafts to move on to other islands, a population crash reduced the once thriving culture to a primitive few survivors (Van Tilburg 1994, 50–53). One wonders, when the islanders cut down the last few trees, what were they thinking? Would we do such a thing?

This is a cautionary tale. The Easter Islanders did not use their resources in a sustainable manner. The combination of deforestation and isolation trapped them on their small island. With no escape and resources used up, the society and the population crashed into a primitive state. The Earth is our island. There is no effective escape to another Earth.

The decisions we make about construction are not unrelated to slowly cutting down all the trees on Easter Island. A simple choice between wood panel interior doors versus flush interior doors is a choice between 800,000 Btu/panel door versus 400,000 Btu/flush door in embodied energy. Which do you choose? Another example is tempered glass versus regular annealed glass. Tempered glass is stronger against breakage, and when it does break it falls apart into many glass granules. Annealed glass is not as strong and it breaks into shards of various sizes that can cut people badly. The building codes require tempered glass in doors and in windows that have sills below 18 inches from the floor. These requirements are to protect people from danger. Regular one-eighth inch annealed glass has an embodied energy of 35,000 Btu/square foot. Tempered glass is made from annealed glass by reheating annealed glass that has been cut to the appropriate size and then quick cooling it. The result is a glass with tension stresses on the surfaces of the glass, which gives tempered glass its strength and granular breaking characteristics. Tempered glass has about double the embodied energy of regular annealed glass, 70,000 Btu/square foot. An architectural choice to extend windows sills below 18 inches is comparable to the Easter Islanders’ cutting down the palm trees for the important job of rolling religious statues down from the quarry to sites near the water.

In thermodynamic calculations a control volume is mentally constructed around the process that is being studied. Then energy and mass flows entering and leaving the process can be accounted for using the first and second laws of thermodynamics. This is a useful procedure to apply to a passive solar design in order to include embodied energy along with annual energy use in design decisions. Decisions about the embodied energy of material choices like doors and glass can be made in a fairly straightforward way as long as the embodied energy information is known. However, a decision about how much thermal mass to use in a passive solar design involves both embodied energy and annual energy use. Likewise the balance between insulation levels and passive solar involves embodied energy and annual energy use.

The Passive Solar Handbook published by the California Energy Commission documents Calpas computer energy simulations for a 2,000 square foot house in various climate locations around California. Heating energy use variations caused by area of south glass and surface area of thermal mass for two levels of insulation for the house are presented in the handbook (Niles and Haggard 1980, 18–38).

The embodied energy of 1,000 square feet of four inch concrete with a quarry tile surface is 83 million Btus. The embodied energy of 1,000 square feet of wood frame floor with a hard wood surface is 18 million Btus. The difference is 65 million Btus. The 65 million Btu number is the additional embodied energy of 1,000 square feet of thermal mass floor over the choice of a wood frame floor.

Data from two locations was used to compare yearly heating energy savings from passive solar with the embodied energy in the concrete thermal mass necessary to achieve the savings (Table 16.1). Santa Maria, in the central coast of California, has a very mild climate (Niles and Haggard 1989, 120–121). Alturas, California, in a northern mountain location, has a much colder climate (Niles and Haggard 1980, 94–95). Dividing the annual passive solar heating energy savings into the embodied energy of the concrete thermal mass provides the years of annual energy savings needed to payback the embodied energy in the thermal mass.

The years to energy payback are all reasonable numbers until a closer look shows that the first 1000 square feet of thermal mass saves 21 million Btus per year, but the addition of another 1,000 square feet of thermal mass only adds a few more Btus of savings. It would be more accurate to compare the marginal energy saving benefit of adding additional thermal mass (Table 16.2).

TABLE 16.1 Simple energy payback of the embodied energy in concrete thermal mass, with the yearly energy savings from a direct gain passive solar heating system

Thermal mass area (sq ft) | Embodied energy (MBtu) | Yearly energy savings (MBtu) | Years to energy payback |

Santa Maria, California, 300 sq ft of south glass | |||

1,000 | 65 | 21 | 3.1 |

2,000 | 130 | 23 | 5.7 |

4,000 | 260 | 25 | 10.7 |

Alturas, California, 300 sq ft of south glass | |||

1,000 | 65 | 21 | 3.1 |

2,000 | 130 | 25 | 5.2 |

4,000 | 260 | 28 | 9.3 |

Source: Niles, Philip, and Kenneth Haggard. 1980. The California Energy Commission Passive Solar Handbook. Sacramento, CA: The State of California Energy Resources Conservation and Development Commission. Pages 95 and 122.

TABLE 16.2 Marginal energy payback of the embodied energy in concrete thermal mass, with the yearly energy savings from a direct gain passive solar heating system

Thermal mass area (sqft) | Embodied energy (MBtu) | Yearly energy savings (MBtu) | Years to energy payback |

Santa Maria, California, 300 sq ft of south glass | |||

1,000 | 65 | 21 | 3 |

2,000 | 130 | 2 | 33 |

4,000 | 260 | 2 | 65 |

Alturas, California, 300 sq ft of south glass | |||

1,000 | 65 | 21 | 3 |

2,000 | 130 | 4 | 16 |

4,000 | 260 | 3 | 43 |

Source: Niles, Philip, and Kenneth Haggard. 1980. The California Energy Commission Passive Solar Handbook. Sacramento, CA: The State of California Energy Resources Conservation and Development Commission. Pages 95 and 122.

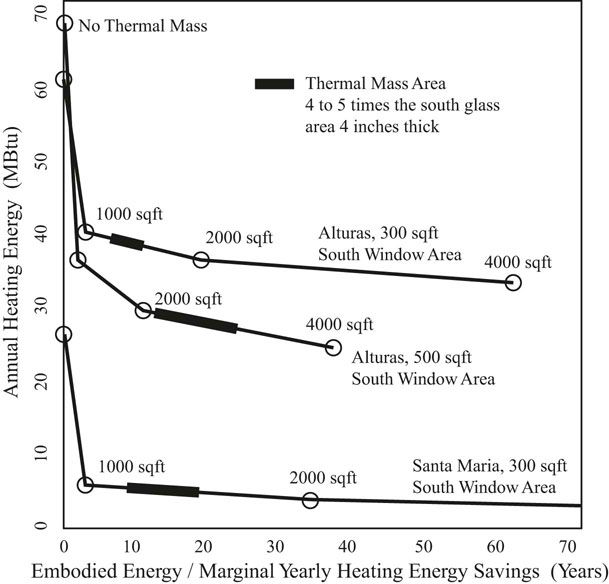

A graph of the marginal annual heating energy use versus the years to payback the embodied energy in the concrete thermal mass necessary to create the savings presents the data more clearly (Figure 16.1). Note the diminishing return of adding excess thermal mass. The rule of thumb to provide four to five times the window area in thermal mass four inches thick is reinforced by this analysis. Four to five times 300 square feet of glass is 1,200 to 1,500 square feet of thermal mass area. This suggested thermal mass area is located on the curves at the beginning of the point of diminishing returns. Installing more thermal mass than this is a waste of the embodied energy involved.

FIGURE 16.1 Marginal embodied energy payback times in years for concrete thermal mass used in a direct gain passive solar heated house in Alturas, California, heating degree days 6,553, and in Santa Maria, California, heating degree days 2,773.

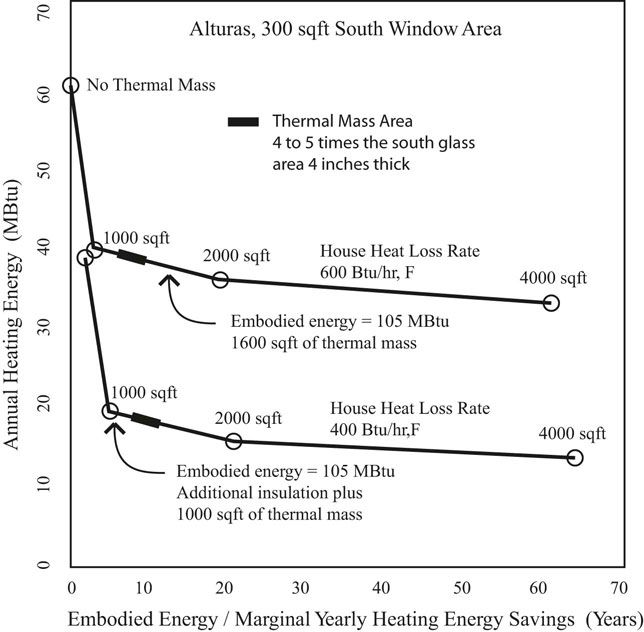

The insulation level on the Alturas house can be increased reducing the heat loss rate from 600 Btu/Hr-F to 400 Btu/hr-F. The additional insulation has an embodied energy of 40 million Btus. The curve of marginal heating energy use versus embodied energy payback for the better insulated house starts out lower and slightly to the right because the insulation saves energy but does cost some embodied energy. It is clear in this comparison that insulation pays back its embodied energy much faster than passive solar pays back embodied energy (Figure 16.2). A sustainable society needs to pay attention to efficiently using its resources, in this case the embodied energy in thermal mass.

In their book Five Degrees of Conservation, Lance LaVine, Mary Fagerson, and Sharon Roe compare the cost benefit of five different houses in Minnesota. They studied a moderately insulated house, a super insulated house, a partially underground passive solar house, a double envelope house, and a house with both active and passive solar. Their results in order of cost effectiveness were as follows. The super insulated house cost $23 per 10 million Btus saved. The moderately insulated house cost $42 per 10 million Btus saved. The double envelope house cost $76 per 10 million Btus saved. The partially underground passive solar house cost $391 per 10 million Btus saved. The house with both active and passive solar cost $398 per 10 million Btus saved (LaVine et al. 1982, 60).

FIGURE 16.2 Marginal embodied energy payback times in years comparing using more concrete thermal mass, with using higher levels of insulation for a solar heated house in Alturas, California, heating degree days 6,553.

These results clearly indicate that the most cost effective way to reduce energy use in houses is to insulate them very well. Adding complicated passive and active solar features decreases the cost effectiveness of the houses.

The embodied energy and cost effective analysis presented above indicate that high gain (large glass area and lots of thermal mass) passive solar doesn’t make sense. The fact that insulation is considerably more efficient at saving energy than high gain passive solar is an opportunity to apply more sophisticated low gain passive solar. Make sure the sun comes into the kitchen and breakfast area in the morning. Also provide morning sun in the master bedroom to provide a gentler wake up than an alarm clock. In addition an eastern location for the master bedroom provides a cooler environment for sleep at night. The living room and or the family room are mid-day uses and thus should have mid-day sun. The dining room, an evening use, can benefit from western light. All of these low gain passive solar features can be handled with a modest glass area and a modest amount of thermal mass since the thermal insulation is doing most of the work.