Economic theory was developed based on the first law of thermodynamics, which is conservation of energy and matter (Beinhocker 2006, 66–68). A basic assumption of economics is that when any source of material or energy becomes scarce, the price will increase which will cause new sources of material and energy to be developed. This assumption was reasonably valid in an earlier age when society was not perched on the edge of sustainability. Standard economic theory assumes an infinite amount of earth ecology to provide materials and energy, and to dispose of wastes (Beinhocker 2006, 68–74).

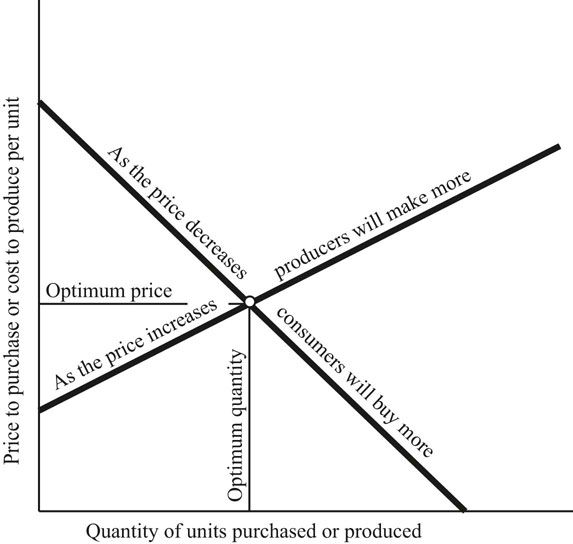

The central idea of economic theory is that supply and demand will create a fair price for goods and services used by the economy. The demand curve represents the fact that, as the price of a product decreases, consumers will buy more of that product. The cost or supply curve represents the fact that, as the price of the product increases, the producer has an incentive to produce more of the product.

The price of a product is determined by where the demand curve crosses the cost curve (Figure 7.1). The curve ignores where the materials and energy come from to make the product and where the waste products from making the product are disposed. This information is compressed into the cost of production. There is no direct way for economic theory to consider the environmental cost of the production. The curve also ignores time. It represents an instant in time. The way economic theory represents time in its calculations is through interest rates. A given quantity of money is worth more today than a year from now because the money could be invested and earn interest in a bank or a return on an investment. This is a correct and valid concept. However, from an environmental point of view the time value of money causes materials and energy to be more valuable used today, in a business venture, rather than being conserved for later use. This brings up the need to define various forms of sustainability.

FIGURE 7.1 Supply and demand curves determine optimum production.

Source: EPA 2010.

The strongest form of sustainability requires that natural capital; forests, rivers, oceans, and so on, be maintained into the future as a separate entity from human made capital. Forests provide oxygen, slow and filter storm water runoff, provide habitat for animals, moderate climate extremes, and, when sustainably harvested, supply wood for future generations. This stronger form of sustain ability calls for the actual service flows from the environment to be maintained over time, rather than the value of the service flows not declining (Wackernagel and Rees 1996, 37).

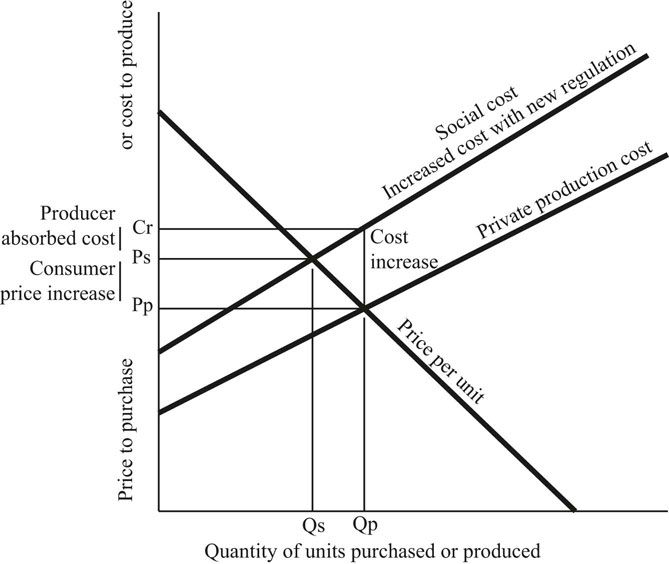

Most industries have a waste flow from their industrial processes. As an example, consider a paper mill located on a river. The waste stream can be dumped into the river at no cost to the paper producer. The waste stream will cause pollution in the river. The demand and cost curve diagram can illustrate the economics of the situation, by including a cost curve that includes the social costs of the pollution (Figure 7.2).

The method that society uses to modify this situation and enforce the social cost on the industry in question is to create regulations that control the amount of pollutant that can be dumped into the environment. The business environment generally resists regulations. They claim that it increases costs, and thus reduces competiveness and potential job growth. The question is, Why resist regulations if the costs can be passed on to the consumer in higher prices? Regulations that require a business to reduce its dumping of pollution into the environment incur an increase in their marginal cost. Demand for the product being produced generally does not change with the imposition of the new regulation. The result is that only part of the cost of the regulation can be passed on to the consumer. The remaining cost is borne by the business, which will reduce profits (Turner et al. 1993, 243).

The supply and demand curves showing the difference between the private cost curve and the social cost curve that includes the cost of pollution can also be used to explore the consequences to society of only considering private costs. There is too much of the product produced. More pollution is produced. The price of the product is not high enough. Since the cost of the pollution is external to the private economic decision there is no incentive to improve the situation. And finally, reuse or recycling of the pollutant is not considered because there is no cost to dumping the pollutant in the environment (Tietenberg 1996, 48).

When a resource is owned privately the owner has a strong incentive to conserve the resource since a decline in the value of the resource is a personal loss. When a resource is owned in common there is a tendency for multiple parties to harvest as much of the resource as they can.

Renewable common property resources, such as fish in the sea, provide an opportunity for a sustainable source of food year after year, if they are managed properly. Consider how a fish population grows. Starting from a small population, the fish growth rate will increase as more fish are available to reproduce. The growth rate will reach a maximum and then decline, as the population of fish reaches the quantity that the environment can maintain. Now consider what happens as a fisherman who owns the fishery catches fish from this population. The population will decline, which will result in an increase in fish reproduction to replace the fish lost to the fisherman. There will be a maximum quantity of fish that the fisherman can take out of the fishery year after year that leaves enough fish uncaught so that they can reproduce to replace the fish taken away by the fisherman. This is the maximum sustainable yield. An owner of the fishery would have an incentive to never go beyond the sustainable yield because he would be concerned with future yields, and since he owns the fishery he would be rewarded with the future yields. Actually, the most profitable yield of fish is less than the sustainable yield because it takes effort to catch the fish and profit is revenue from the catch minus effort. Profit is maximized at yields less than the sustainable yield where, since there are more fish available, they are easier to catch (Tietenberg 1996, 272–276).

FIGURE 7.2 Including the social cost of an industry’s pollution with regulations causes changes in price and quantity produced.

Source: EPA 2010.

When the fishery is owned in common, problems arise. No one fisherman can be assured that his maintaining fish catches at or below the sustainable limit will reward him with future fish catches year after year. So every fisherman in his self-interest catches as many fish as possible. This drives the catch beyond the sustainable limit, and, as the technology of catching fish improves, the fish population can be driven close to extinction (Tietenberg 1996, 280).

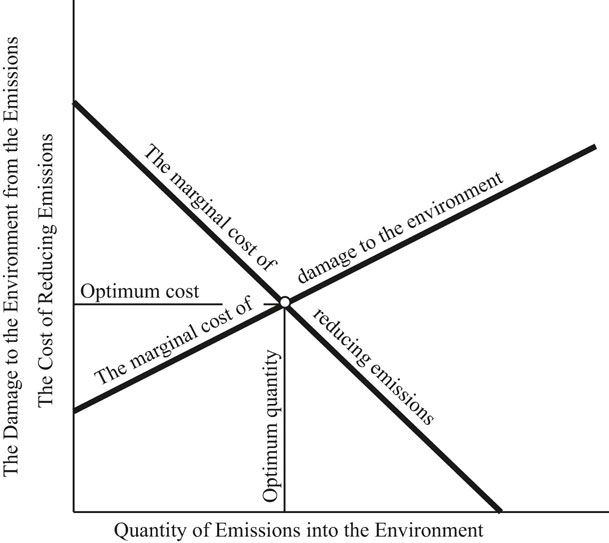

Society produces waste in various forms. Economic theory can help determine the optimal amount of effort to apply. The cost of processing waste so that it does not reach the environment increases exponentially as the process approaches the point of allowing no waste. The cost of the marginal damage to the environment increases exponentially as more waste is allowed to be dumped into the environment. Where these two curves cross is the optimal amount of waste processing (Figure 7.3) (Turner et al. 1993, 254).

FIGURE 7.3 The economics of determining optimum waste disposal into the environment doesn’t consider how much waste the environment can handle.

Source: EPA 2010.

This analysis is purely economic. There are two problems. The first is, Can the environment handle this amount of waste? The second is, How do we set a value on damage from waste disposal into the environment? A strong sustainability response to this problem would be to determine the amount of waste that the environment in question can process naturally. And in addition, strong sustainability would try to find an industrial process that could use the waste in question as an input. Waste is food in a natural ecosystem.

The use of paper in the newspaper industry provides an example of decisions about waste streams The cost of using virgin pulp to make new paper starts high at zero recycling and curves down to no cost at 100 percent recycling. The cost of using recycled paper starts at zero when no recycling is used and increases to a high amount when all recycled paper is used. Adding these two curves together produces a private optimum cost curve resulting in a decision to use a mix of virgin and recycled paper that minimizes costs. There are social costs related to the disposal of the paper that is not recycled. There is a cost to the environment caused by the waste stream degrading it. The cost to the environment starts high, with no recycling of paper, and decreases as recycling increases. The social optimum recycling is the sum of the private cost curves and the social cost curves. The social optimum calls for the recycling of significantly more paper than the private optimum (Tietenberg 1996, 187–189).

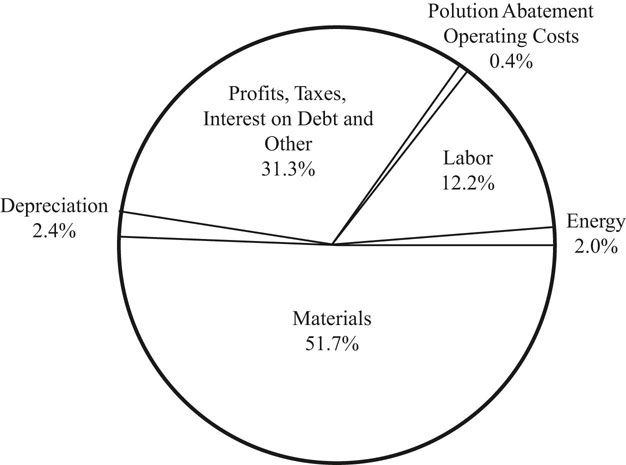

FIGURE 7.4 Pollution abatement costs are a small percentage of total manufacturing costs.

Source: EPA 2010.

Since the social costs are external to the private economic decision, it is difficult to achieve the social optimum recycling amount. The traditional answer to this kind of problem is a government regulation that requires the social optimum recycling. But, as we saw earlier, only part of the cost of the regulation can be passed on to the consumer as a price increase so businesses resist regulations. However, the average pollution abatement cost of manufacturing companies in the United States is only 0.4 percent of operating costs, and only 1.2 percent of operating costs in the paper industry, which has the highest pollution abatement costs (EPA 2010, 9–7).

Economics can be applied to the optimum harvesting of wood from a forest. When a forest starts growing the volume of wood produced increases rapidly. This is followed by a period of constant growth in the volume of wood produced. Finally, as the forest matures the volume of wood produced begins to decrease, reaching a point where the mature forest has no increase in wood volume. From an economic standpoint, there are two points where harvest is considered. The first harvest point is at the point where the rapid increase in volume of wood levels off to steady growth. After this point incremental growth is declining. The second harvest point is at the end of the steady growth period before the declining growth of the maturing forest begins. After this point there is a decreasing volume of wood produced each year (Tietenberg 1996, 248–254).

None of this decision making considers the ecological value of the forest to produce oxygen, and provide habitat for a diverse population of flora and fauna, some of which could turn out to be very valuable to society.

Large oil spills cause damage to the environment, which causes economic damage to the people who live in the area of the spill and create their living from the environment. As the amount of precaution is increased the expected penalty payout decreases and the cost of the precaution increases. The intersection of these two cost curves would represent the optimum amount of precaution. However, the oil companies are large and wealthy so they can afford armies of lawyers to defend themselves against payouts. The end result of this is that decades can go by before payouts are made. Because the time value of money reduces the penalty payout amount, the penalty amount is less than it would have been, resulting in a reduction of the optimum amount of precaution taken by the oil companies (Tietenberg 1996, 448–450).

The economy of the United States and the world needs to grow at a rate of 3 to 4 percent per year to be considered healthy. This is a problem. The material resources of the Earth are limited, and the ability of the Earth to absorb the waste products of economic growth is also limited. A 3 percent per year growth rate results in a doubling in 23 years. A 4 percent per year growth rate results in a doubling in 18 years. To envision the consequences of exponential growth consider as an example a suburban county outside a large city. Only 25 percent of its land area is covered with subdivisions and strip malls, which leaves plenty of open space for quality of life. If this county has a growth rate in land use of 4 percent per year, 18 years from now the county will be 50 percent covered with subdivisions and strip malls, and in 36 years all of the land area of the county will be covered with subdivisions and strip malls. If the county council initiates Smart Growth concepts and can reduce the land use growth rate to 2 percent per year, the county will be half covered in 35 years and completely covered in 70 years. Even modest growth, if it is exponential, causes explosive results.

Herman Daly’s and John Cobb’s book, For the Common Good, tries to address the problem of growth. One issue they present is that the gross domestic product (GDP) does an incorrect job of measuring the real gross domestic product. The following two examples illustrate the measurement problem. The GDP counts as a positive number the oil we take out of the ground and burn up to fuel our society. This would be equivalent to a person spending part of his savings in a year but considering it current income for that year. A related problem is oil spills. When a large oil spill happens, such as the Exxon Valdez, the cost of the cleanup is considered a positive addition to the GDP. This would be equivalent to a person spilling oil or something else on their living room carpet and then considering the cost of cleaning up or replacing the carpet as positive income for that year (Daly and Cobb 1994, 62–84).

Herman Daly has produced a per capita index of sustainable welfare. The sustainable index, which corrects for the issues mentioned above, is relatively flat. It shows a slight growth in the mid-1960s and a slight decline in the late 1970s, with a slow rise after that (Daly and Cobb 1994, 464).

We need to discover how to create an economy that grows qualitatively, not quantitatively. At some point we will all have to decide that there are limits on the amount of goods we can produce and own. Quality of life will have to outweigh having three more and bigger wide screen TVs.

It seems clear that depending on economic theory alone to guide society’s decisions about the environment is a mistake. As an example, consider that

a complete loss of expected world GNP 100 years from now, at current interest rates, would have a present value of about one million dollars. This is trivial in comparison to the present value of potential loss of controlling the greenhouse effect because clean up monies would be spent in the near future.

(Tietenberg 1996, 394)

There are two approaches to this problem and we may need to use both of them. One approach is to admit that we can never know enough to manage the entire ecosystem of the earth. The result of this admission would be to leave enough wild ecosystems alone so they can provide important natural services like oxygen production to keep the human race alive. The second approach would be to research how the ecosystems of the world work so that we can live in a non-destructive relationship with nature. Ecosystems are complex and self-affine across many scales. This diverse complexity creates stability. A failure of one or even many individual components doesn’t cause collapse. Unfortunately our current economic system tends to find easy feeding in focused areas like the financial sector feeding on mortgage securities and their related derivatives. The result of this monoculture is boom and bust. The human economy needs to mimic the natural world and become more diverse, complex, and layered across size, from large to small.