7

Liturgical Change

CHURCH ARCHITECTURE BEFORE LITURGICAL REFORM

The previous chapter aimed to give a brief narrative of the liturgical movement in British Roman Catholic church architecture through a small number of protagonists, examining people and buildings that were unusually advanced in their thinking and influential on later developments. This chapter considers the more typical experiences of church architects and clergy in Britain during this time of change, looking at the transformations that took place in the liturgy from the 1950s until the 1970s, the influence of NCRG debates on architects, and their effects on parish church architecture.

I begin by looking at the architectural aspects of liturgy before reform. Liturgical movement writing viewed contemporary liturgy as the culmination of a long deterioration characterised by clericalisation, the liturgy becoming distant from the people, performed in splendidly decorated chancels divided from the laity and viewed from afar, with the congregation reduced to mere spectators. Such accounts, however, were motivated by a reforming agenda. While there is evidence for passive congregations, the basilican form itself did not preclude participation and could be designed with participation in mind: practices were more complex than the theory suggests.

Most large churches of the 1950s and early 1960s had long rectangular naves, but it had been an important principle since the Counter Reformation, accepted with renewed interest in Britain in the late-nineteenth century, that everybody should see the sanctuary and follow the Mass. Seeing was the key, yet visibility was a principle that the liturgical movement questioned, since vision implied spectatorship whereas ‘active participation’ demanded action. The NCRG and others therefore criticised churches that appeared to limit lay involvement in liturgy. The separation of sanctuary and nave with solid altar rails, high contrasts of light between nave and sanctuary, and a monumental distant altar implied a supposedly faulty conception of liturgy as a spectacle.

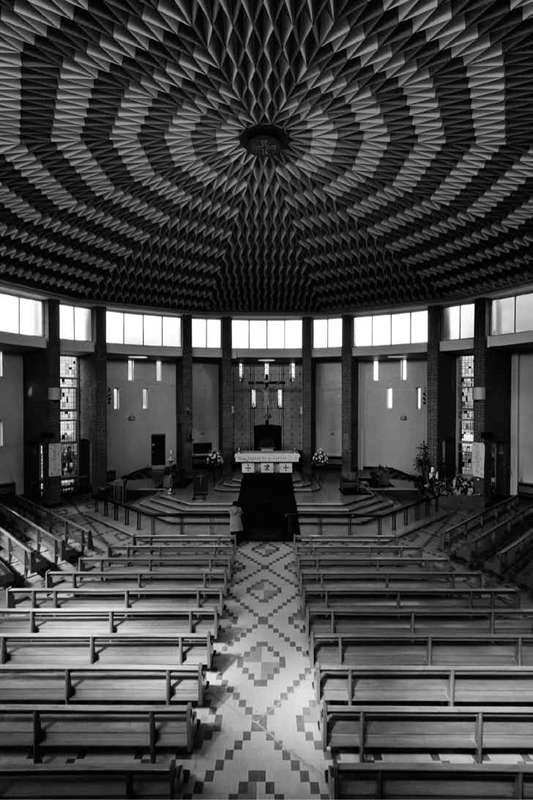

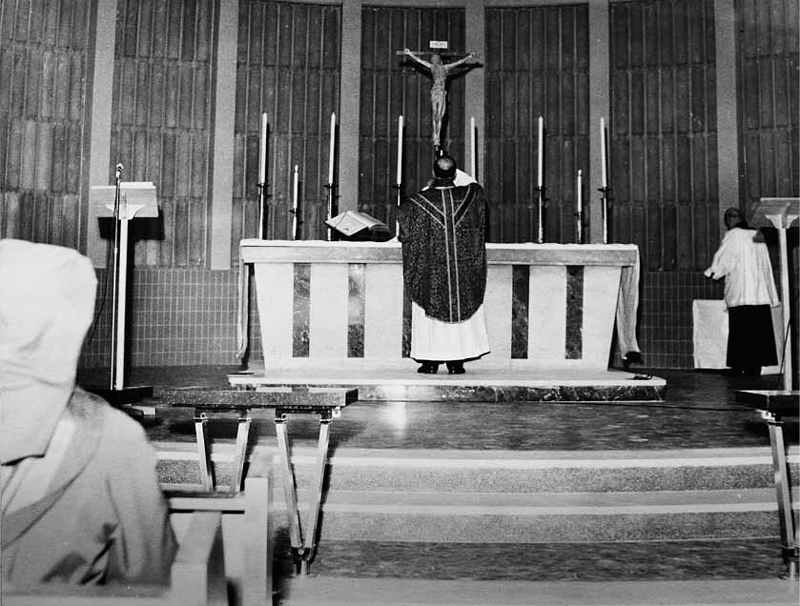

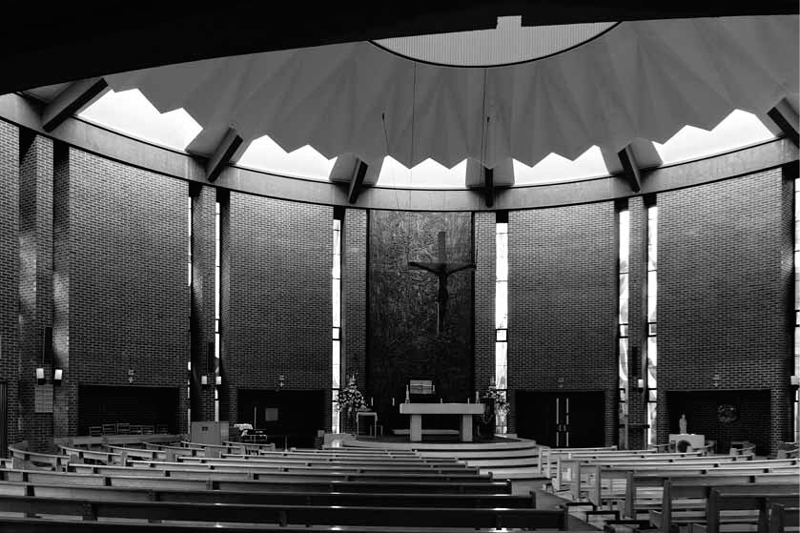

Britain was relatively late in adopting European styles of liturgical innovation and participation. While the dialogue Mass was common across France and Germany by the 1940s, as late as 1958 at least six British dioceses still prohibited it.1 In 1958, the Vatican allowed parishes to say the dialogue Mass without diocesan permission, and only then did it become common in Britain.2 Yet even in the 1960s, the dialogue Mass was often rare enough to be remarkable.3 Dioceses varied widely: ‘In Edinburgh, dialogue Mass is widespread and congregational participation is often excellent’, wrote one observer in 1962. ‘To go to Glasgow to Mass is to pass into a different world, mute and frustrating.’4 The Latin Mass without congregational participation remained normal in many places until relatively late. Mass facing the people was rarer still. Even when a priest followed the liturgical movement, he would not necessarily face the congregation. At Desmond Williams’s circular church of St Mary in Dunstable, certainly influenced by liturgical movement notions when it was designed around 1960, the altar was placed against a reredos at one side of the seating (Figure 7.1). Early designs for the circular church of St Catherine of Siena at Birmingham similarly placed the altar against a reredos at the rear of its platform, and though it was built with a central altar, the opening Mass of 1964 was said facing away from the congregation (Figure 7.2).5

The faithful did not always apparently want to participate in the liturgy. The liturgical movement aimed to direct the congregation’s attention to the liturgy because many worshippers indulged in unrelated devotions during the Mass. These included public recitation of the rosary, advocated during Mass throughout October by Leo XIII in 1884 and sometimes maintained in Britain until the Vatican discouraged ‘pious exercises’ during the liturgy when promoting the dialogue Mass in 1958.6 A common objection to the dialogue Mass, meanwhile, was that it disturbed the worshipper’s meditation and the church’s feeling of sanctity.7 There were further ways in which congregation and liturgy could be divided, as sociologists John Rex and Robert Moore studying Irish immigrants at a temporary church in Birmingham found:

The … Mass Centre is filled at each Mass with men, women, children, and babies; these latter two groups maintain continuous diversions and a level of noise that makes it difficult to follow the service. Sermons are short and the setting of the liturgy on a stage under stage lights with the congregation below and occasionally engulfed by noise and disturbances, separates the people from the ritual and heightens the observer’s sense of ‘us down here’ watching something going on ‘up there’.8

Before Vatican II, the normal experience of liturgy for most Catholics was of a Latin rite performed by the priest, often with psychological or social barriers to participation.

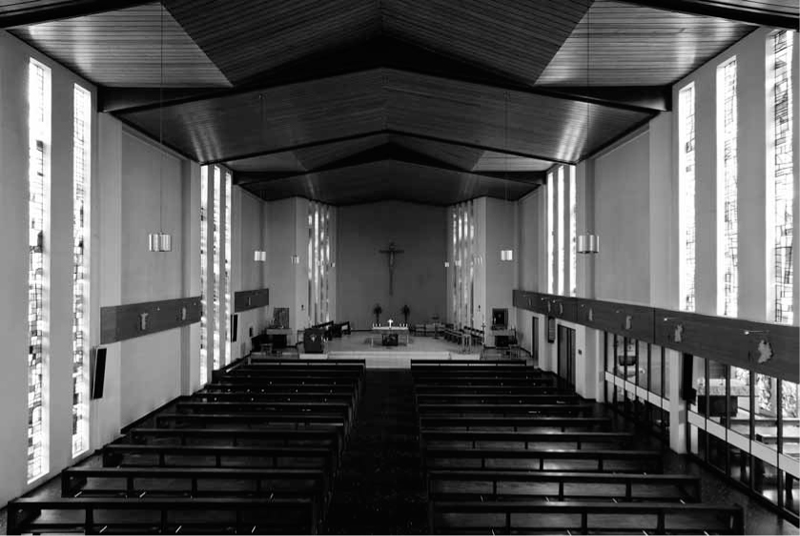

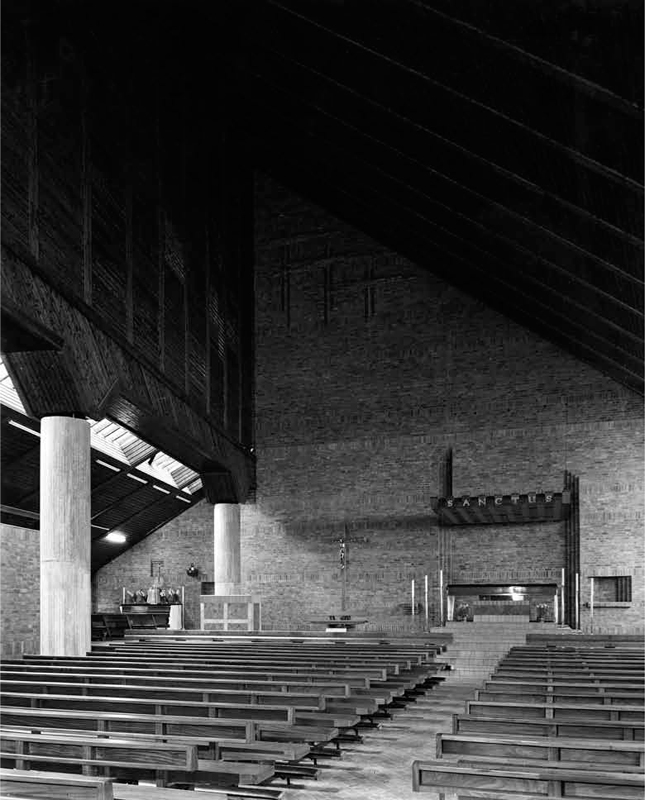

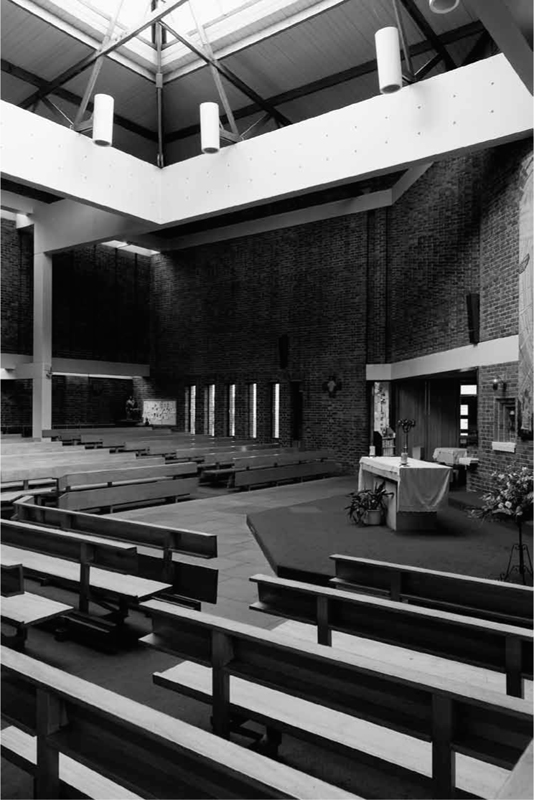

Architects could therefore endorse modern architecture without engaging with the liturgical movement. Long, narrow churches with splendid sanctuaries were built for clergy without a culture of liturgical innovation. Sanctuaries were often framed as separate spaces, as seen at Reynolds & Scott’s Sacred Heart, Gorton, Manchester (Figure 7.3); or more subtly with wider structural supports and a richer ceiling decoration, as at the same architects’ church at Hackenthorpe in Sheffield. St Stephen, Droylsden, in Manchester by Greenhalgh & Williams, though it was modern in style and its architects were aware of the liturgical movement, employed a conventional basilican plan: prominent brick walls flanked the sanctuary and splayed out towards the nave, the altar rail extending across them, while the altar was typically monumental in form and set against a reredos (Figure 7.4). Greenhalgh & Williams conceived of congregational participation primarily as a visual emphasis on the sanctuary achieved by making it the dominating feature of the building, visible to all and attracting attention through scale, richness, light and framing devices.

7.1 St Mary, Dunstable, by Desmond Williams, 1961–64. The altar position has not changed since completion, but it was originally furnished with the tabernacle and six candlesticks along its rear edge. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2013

7.2 St Catherine of Siena, Horsefair, Birmingham, by Harrison & Cox, 1961–65. Undated photograph of Mass shortly after completion of the church. Photographer unknown. Source: parish archive. Courtesy of the Birmingham Roman Catholic Diocesan Trustees

Liturgical movement writers criticised churches with proscenium arches, where the sanctuary seemed like a stage and the liturgy appeared theatrical. By 1950s churches were only occasionally built with such a feature: the Immaculate Conception in Leeds by R. A. Ronchetti, for example, was a simple brick church with passage aisles, where deep brick chancel arches framed the altar and yellow glass transmitted an otherworldly glow to the sanctuary. The most theatrical new churches were, however, those that were intended for temporary use. Early church buildings in the life of a parish were often dual-purpose halls, serving as churches on Sundays and ceremonial occasions and otherwise as social halls, intended for purely secular use once a church was built. Their secular uses often included theatre or music, so a stage would occupy one end opposite the sanctuary or double as a sanctuary on Sundays, as Rex and Moore described. Separate sanctuaries would be closed off by folding partitions. When opened and folded up at the sides, these partitions visually defined the sanctuary like curtains, while screens above closed off the openings in these portal-framed interiors. Such theatrical elements could be interpreted as liturgically desirable. When the parish of St Mary at Levenshulme in Manchester bought a cinema for conversion to a temporary church, their architects Mather & Nutter explained its liturgical advantages. The sanctuary occupied the raised stage and the congregation the auditorium, whose raked floor gave worshippers ‘an excellent view of the Altar from all parts of the Church’. Concealed lighting illuminated the proscenium strip, painted red, ‘which gives richness to the decoration and focuses attention on the Sanctuary’.9

7.3 Sacred Heart, Gorton, Manchester, by Reynolds & Scott, 1958–62. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2013

7.4 St Stephen, Droylsdon, Manchester, by Greenhalgh & Williams, 1958–59. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2012

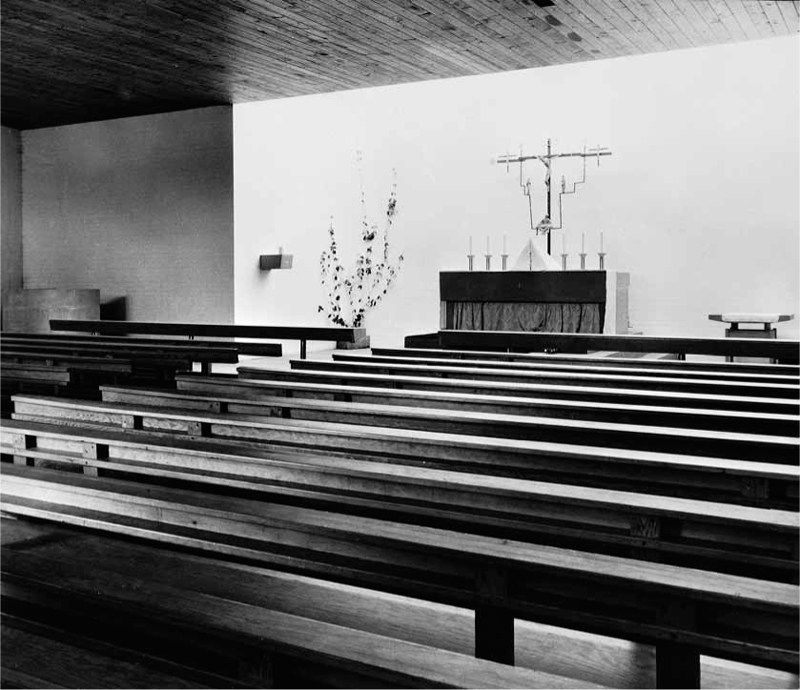

7.5 St Paul, Glenrothes, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1956–58. Photo: William Toomey, c.1958. Courtesy of Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Library Photographs Collection. Source: Glasgow School of Art

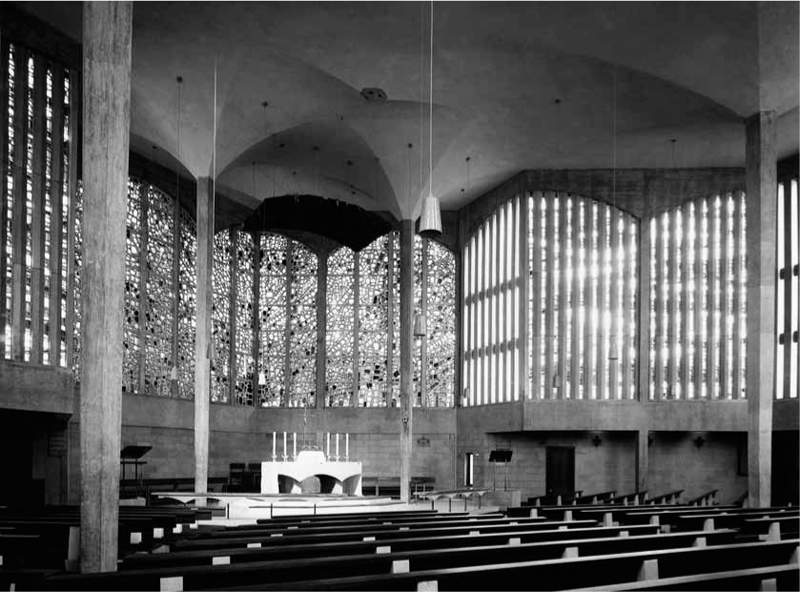

Despite receiving much praise from NCRG members, Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s church of St Paul, Glenrothes was criticised for a theatrical sanctuary.10 Its altar was placed in a taller space than the nave, illuminated from a concealed lantern (Figure 7.5, Plan 2b). ‘The recess in which the altar is placed tends to form a proscenium arch, and to produce a slightly stagey effect’, wrote Edward Mills, an effect he thought was increased by the use of natural light. William Lockett added that this aspect of the design would detract ‘from the congregation/priest relationship’.11 Though they were building for the relatively progressive diocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh, Gillespie, Kidd & Coia were based in liturgically conservative Glasgow without the benefit of a clerical culture of interest in the liturgical movement. Their church of St Bride at East Kilbride, for example, may have been avant-garde in style but was liturgically conventional, with a large altar and tabernacle in a raised sanctuary at one end of a long nave. It was opened in 1964 by the bishop of Glasgow, James Scanlan, with a pontifical high Mass in Latin making no concessions to the Second Vatican Council’s ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ of the year before.12

Patrick Nuttgens gave a talk about St Bride the following year in London, followed by a discussion attended by Coia, Metzstein and MacMillan. Nuttgens praised the church’s architecture, but admitted that the reinforced concrete gallery along one side of the nave created an awkward space underneath it: ‘during Mass’, he noted, ‘the whole area of the church under the side gallery was crowded with people not paying attention’. Its design was also considered too inflexible for the liturgical changes that were now expected. Winkley, then beginning work on St Margaret, Twickenham, ‘suspected that the building was more obsolete than people seemed to realize’. The acoustics were also criticised: electrical amplification was thought to create a distancing effect between clergy and congregation and should have been unnecessary. The architects admitted that their client’s brief had been incomplete and that they had been concerned less with liturgical function than with the creation of a numinous space. Coia concluded that ‘at the end of the day, the church was a place for religious worship and had to feel right for that purpose’.13

By then, however, Metzstein and MacMillan had begun to embrace the liturgical functionalism of the NCRG with more centralised church designs. St Bride had been designed in 1958, before the liturgical movement discourse in architecture had become widespread. When the Architectural Review asked the architects for material for an article on St Bride after its opening, the architects requested publication of another church instead, St Joseph at Faifley in Glasgow, since it was ‘of a more advanced liturgical form’.14 St Joseph, designed in 1960 and opened in 1963, was the firm’s first church to depart from a linear plan, with seating on three sides of the sanctuary, all contained in a single pitched-roofed volume (Plan 2c). Even this building was designed for the old liturgy, however; its altar platform at the far side of the sanctuary platform, and the altar on the far side of its platform, designed for a priest to stand in front of it facing away from the people, gave the church a directional quality (Figure 7.6). The tabernacle was originally on the altar and a conventional heavy pulpit was constructed outside the sanctuary.15 Faifley drew on an awareness of liturgical movement principles, yet without anticipating the new liturgical practices that were soon to become the norm.

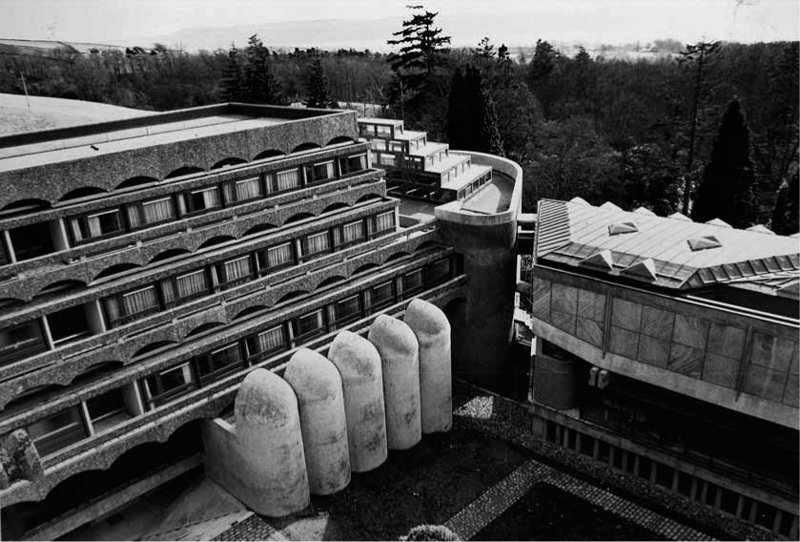

At Glenrothes, Gillespie, Kidd & Coia incorporated a liturgical arrangement common in many other churches across Britain of this period and before, but which would soon be regarded as a solecism: a devotional side altar behind the altar rails and within the space of the sanctuary. Liturgical movement writers, evoking the convention of the altar as a symbol of Christ, advocated only one altar in the sanctuary. Secondary shrines were thought to distract the congregation from the liturgy, and so, as the Second Vatican Council confirmed, they were to be few in number and visually discrete. Yet before the council many new churches were built with side altars inside the sanctuary, even by architects who knew of the liturgical movement in the 1950s, including Greenhalgh & Williams at St Columba and Our Lady of Lourdes in Bolton. Side altars had a necessary function in busy parishes and wherever there were several priests. Until the mid-1960s, priests had to say Mass every day. The result was a great many ‘private Masses’, as they were called, invariably said at side altars with little ceremony. Sandy & Norris’s chapel at Ratcliffe College in Leicester, for example, was dotted with side chapels in niches around the nave to cater for its ordained teaching staff. Even as late as 1967, the chapel by Greenhalgh & Williams at the Salesian school at Thornleigh in Bolton had only one side altar in the body of the chapel in response to the Second Vatican Council, yet a separate priests’ chapel was built behind it with ten small altars where staff could say their private Masses.16 Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, similarly, incorporated rows of silo-like side chapels at their seminary, St Peter’s College at Cardross (Figure 7.7).17

7.6 St Joseph, Faifley, Glasgow, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1960–63. View after early reordering, c.1965, when the tabernacle was moved to an altar behind the sanctuary. Photographer unknown. Source: Glasgow School of Art

In 1964, the first Vatican-approved experiments with concelebration took place, and the rite was soon approved for gatherings of clergy, replacing individual Masses with a liturgy celebrated by several priests around a single altar. Cardross was therefore outdated when it opened. So, too, was Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, its ring of side chapels largely redundant by 1967: the cathedral was opened with a concelebrated Mass, to which its sanctuary was considered perfectly suited. Ample sanctuaries with broad altars were now desired, such as that at Clifton Cathedral, where only one secondary altar was included.

7.7 St Peter’s College, Cardross, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1959–67. The ground-floor chapel was located at the end of the left-hand block, embraced by side chapels in towers. Photo: Thomson of Uddingston, c.1967. Source: Glasgow School of Art

While centralised plan types were being explored in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the prevailing type remained the big basilica with passage aisles or the single-volume rectangular box. Many such churches were built in the Archdiocese of Westminster, where Archbishop Godfrey espoused traditional forms in church architecture even while acknowledging the need for lay participation.18 John Newton of Burles, Newton & Partners built several such churches for Westminster with plain and open sanctuaries for liturgical visibility. Newton’s basilican church of St Aidan at East Acton opened the same year as his church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Hayes, an even larger and more impressive modern basilica seating up to a thousand (Figure 7.8). Constructed in steel, it had a wide nave with sail-like vaults, its aisles filled with seating to maximise capacity. Even as he began exploring liturgically innovative plans, joining the NCRG, Newton continued to design longitudinal churches. Our Lady, Queen of Apostles at Heston, opened in 1964 but designed in 1961, retained seated aisles and framed the sanctuary with paired columns, though its broad interior was stark to focus attention on the liturgy (Figure 7.9).

St Francis de Sales at Hampton Hill was designed before the ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ had been promulgated, but despite its longitudinal plan it could still be interpreted according to the constitution’s principles (Figure 7.10). It had a single nave and wide sanctuary, and only one side chapel, set back and partly screened from the pews. Newton wrote about his design using liturgical movement ideas, saying that he had excluded stylistic mannerisms so that ‘the fabric of the church as an enclosing envelope does not exert itself but only contributes to the worship of the faithful’. One important function was that ‘the Priest is to be seen in the central position in the place of Christ with the people around him and united with him in what is being done by him’. Sanctuary and nave had to remain distinct but yet unified enough to express the unity of priest and people in the Mass.19 A group of parishioners wrote a further interpretation of the church’s architecture in terms close to those of Hammond and Maguire: ‘the important consideration is that the Liturgy can function in dignified surroundings where the people of God form one worshipping community’, they wrote. However, ‘one of the more recent problems of modern church architecture is that the round and D-shaped churches, which were regarded by many people to be the answer to the present demands of the Liturgy, are not fulfilling that function’. Noting that the church had been planned several years before, they nevertheless thought it

7.8 Immaculate Heart of Mary, Hayes, London, by Burles, Newton & Partners, 1958–62. View towards choir gallery over entrance: Stations of the Cross by Arthur Fleischmann. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

7.9 Our Lady, Queen of the Apostles, Heston, London, by Burles, Newton & Partners, 1961–64. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

7.10 St Francis de Sales, Hampton Hill, London, by Burles, Newton & Partners, 1964–67. Nave windows by Jerzy Faczynski and J. O’Neill & Sons; chapel on the right with stained glass by Gilbert Sheedy. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

admirably suited to the new Liturgy. The people of God are gathered in one group and speak with one voice; the free-standing Altar at low level, with the priest on one side and the people on the other … lends itself to the familiar pattern of the Last Supper. Together, very much together, we offer the Holy Sacrifice of worship.

More allegorically still, they thought that the ‘frieze’ – simple timber panels containing the Stations of the Cross – could be considered ‘an extension of the priest’s arms … [seeming] to enfold the whole congregation in the arms of Christ’.20 Though the longitudinal church often did result from liturgical conservatism, therefore, it did not necessarily equate to a passive or devotionally minded laity but could be rich in its meanings and open to liturgical emphasis.21

CANON LAW AND LITURGICAL FURNISHINGS

A perennial obstacle to reform in the Roman Catholic Church in Britain was a legalistic mentality. Every aspect of the liturgy and many aspects of church design were governed by canon law and the rubrics of the Roman Missal. These constraining texts made it hard for those who wished to introduce change to do so; yet the rules themselves could also stimulate creativity, and reading them with liturgical movement principles in mind was one method of reform. The Second Vatican Council cut across this approach by interrupting the continuity of canon law, leaving creativity suddenly unconfined. Before that moment of interruption, architects exercised their ingenuity within and through these strictly held parameters.

The rule-bound attitude in British Catholicism differed from the more contingent approach to canon law that was often seen on the continent. Joseph Rykwert, writing for a French audience, saw the British approach as a barrier to the development of a modern church art and architecture: ‘In England more than elsewhere … Catholics are obsessed by a meticulous liturgical observance’, he wrote. He explained that at an exhibition in London of modern French church architecture ‘even the most receptive critics fixated on one thing: that the candles on the altar are rather low, and that there are too often only two instead of six’.22 Rykwert believed the development of modern church architecture in France had been possible because of a freedom from rigidly applied rules. Such restrictions as the number, style and position of the candlesticks were viewed as formal conventions that architects who took a traditional approach accepted; modern architecture, in contrast, was defined by its desire to transgress past conventions to envision new forms. Architects, however, generally prohibited from making such transgressions, probed the interstices of the text-bound rubrics to exploit their ambiguities and, in the process, revealed their contingency.

O’Connell’s Church Building and Furnishing and articles in the Clergy Review explained and clarified the rules on liturgy and church architecture. His book could be read in different ways. Because it explained the laws in detail, with diagrams and photographs to show the correct forms of liturgical furnishings, it could lead architects and clergy to an especially rule-based attitude, and indeed the book was widely consulted for this purpose. On the other hand it also explained the historical development of liturgical furnishings and the origins of the rules, suggesting their contingent status and arming architects with knowledge that could unlock possibilities for new forms, especially through an understanding of historical precedents that might seem more ‘authentic’ expressions of purpose than the current forms of furnishings. O’Connell accepted the liturgical movement and in setting out the forms and histories of liturgical elements wanted to make them better understood. Canon law did not stipulate general forms for churches other than a vague condition of adherence to tradition, giving wide potential for innovation in church design, but when it came to smaller liturgical components the Church gave detailed prescriptions, mostly derived from liturgical texts. In diagrams and photographs O’Connell showed the acceptable forms for the altar: a stone table top (the mensa) with stone supports that could have an infill to give a solid form and a recess (the sepulchre) to contain relics, all aspects implied by the consecration rite, which required the anointing of the joints between altar and supports and the insertion of relics. Six candlesticks had to be set on the altar and a tabernacle fixed to it in the centre; a stepped platform raised it up and a ciborium or baldachino sheltered it. The altar also had to be covered with prescribed cloths including a frontal and the tabernacle had to be veiled. Finally, there had to be a crucifix, ‘not an accessory, but the principal thing on the altar’.23

The element that would become most passionately debated after the Second Vatican Council was the tabernacle. O’Connell explained how the Blessed Sacrament had originally not been the subject of private devotions and that at first it had been reserved away from the high altar, only becoming associated with the altar in the Middle Ages and fixed upon it from the seventeenth century (except in cathedrals and monasteries where the high altar was used for choral services). Twentieth-century canon law prescribed this arrangement and the Assisi Congress temporarily reinforced it: after delegates had discussed the desirability of alternative locations for the tabernacle, Pius XII’s speech denounced attempts to separate tabernacle and high altar, and the Vatican’s Sacred Congregation of Rites issued a ruling in 1957 restating the existing law and rejecting innovation.24 In Britain such regulations were accepted literally, as the argument between priest and bishop at Our Lady of Fatima in Harlow shows.

Dioceses would often take an interest in liturgical furnishings, censoring anything that seemed incorrect or unprecedented. Archbishop Gray of St Andrews and Edinburgh, for example, visited Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s church of St Mary and the Angels at Camelon in Falkirk on its completion in 1960 and gave a list of alterations to the parish priest Anthony Flynn. The candlesticks, he insisted, had to be separate, suggesting that the architects had designed a combined version that did not comply with the rules. The side altars also had to be repositioned to be centred within their spaces and the baptistery was to be provided with railings according to canon law.25 At St Paul, Glenrothes, a few years earlier the architects had proposed an altar in the form of a single large block, to be told by Gray that, according to O’Connell, the supports and table top had to be distinguished and their joints visible.26 As a result they designed an altar more table-like in form, though usually invisible beneath its frontal. Similarly Archbishop Godfrey of Westminster demanded that architects submit detailed drawings of liturgical furnishings, especially if the design was likely to be unusual. David Stokes, for example, was quizzed over Greenford, asked for a detailed drawing of the altar and baldachino and told to show the parish priest a similar built example.27 In Liverpool, the Sites and Buildings Commission checked liturgical furnishings and scrutinised plans. Not only did the diocese prevent Weightman & Bullen from placing the tabernacle in a separate chapel at St Ambrose, Speke, they also made small modifications to their other designs. At St Catherine, Lowton, the altar platform had to be raised from one step to three in line with convention; at St Ambrose, an initial proposal for a tabernacle raised on legs was swiftly rejected; and at Leyland, the ceramic suspended crucifix by Adam Kossowski was approved but was interpreted as ‘an ornament or decoration’ and a liturgical altar cross was also required.28 In all these cases the architects were attempting to change the normal formulae for liturgical elements, even if only in subtle ways. When architects repeated designs from one church to another, they often did not need to submit drawings for special approval but could simply indicate a precedent that had already been approved. Diocesan scrutiny was therefore a powerful incentive against innovation.

Sanctuaries generally had a familiar appearance, a recognisable Catholic form that varied little from one church to another. Nevertheless there was room for creativity within the rules and a variety of treatments of liturgical objects in modern churches. For example some form of canopy over the altar was a canonical requirement. In traditional guise it might follow the early Christian or Romanesque ciborium. One striking example was that of Hector Corfiato’s St William of York at Stanmore, where art deco style columns in black and gold supported a hat-like confection over the high altar, in a church that the parish priest had asked to be ‘in the style of the Romanesque’ (Figure 7.11).29 The more usual treatment of this feature was an ornamented suspended baldachino such as those at St Stephen, Droylsden, and St Boniface, Salford, elegantly designed to complement the modern architecture of their churches. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was often reinterpreted as a corona. At Massey & Massey’s St Raphael, Stalybridge, for example, a square rig of lights hung from the centre of the dome over the freestanding altar; and at St Teresa of Avila in St Helens by William & J. B. Ellis, opened in 1965 but designed before the Second Vatican Council, a cylindrical crown of timber slats was suspended over the imposing marble altar (Figure 7.12). Gillespie, Kidd & Coia experimented with different approaches: at St Charles in Glasgow and St Bride at East Kilbride, concrete cantilevered projections constituted baldachinos; at their church of the Sacred Heart, Cumbernauld, open coffers in the timber ceiling suggested this form (Figure 7.13). The canonically required feature became a pretext for expressive architectural experiment, in some cases integrated into the structure of the building.

The design of the altar was especially carefully considered. The rule that the front should be covered was often ignored, however, in favour of a permanent decorative treatment of the altar face. Altars were generally made to resemble single heavy blocks, concealing their internal structures with facings of stone, and designed to complement other furnishings. At St Nicholas at Gipton in Leeds by Patricia Brown and David Brown of Weightman & Bullen, for example, liturgical movement aims were clearly stated by the architects, yet the treatment of the altar remained conventional, if stylistically modern: it was broad and deep and placed close to the rear wall of the sanctuary, which was described as a ‘reredos’ and ornamented with pieces of gold mosaic (Figure 7.14).30 The altar had a heavy overhanging mensa, and its base was clad in white marble, its front decorated with slate panels containing gilded crosses. Its scale and richness made the altar a strong visual feature complementing the dramatic modern interior. At the Holy Apostles, Pimlico, London, a modern basilican church by Hadfield, Cawkwell & Davidson, the altar was set against the rear wall. A sandstone mensa rested on a rectangular base with slate panels engraved with gilded symbols, the alpha and omega and a central image of the lamb symbolising the sacrifice of Christ. At both Gipton and Pimlico the treatment of the altar extended to the communion rails: brass and white marble in Leeds, slate with gilded figures of the Apostles in London.

7.11 St William of York, Stanmore, London, by Hector O. Corfiato & Partners, 1960–61. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

7.12 St Teresa, Newtown, St Helens, by William & J. B. Ellis, 1964–65. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2008

7.13 Sacred Heart, Cumbernauld, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1961–64. Stations of the Cross in dalle de verre by Sadie McLellan. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2011

7.14 St Nicholas, Gipton, Leeds, by Weightman & Bullen, 1960. Altar and communion rails: the sanctuary has been partly reordered since completion. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

7.15 St Theresa of Lisieux, Borehamwood, London, by F. X. Velarde Partnership, 1961–62. Photo: Elsam, Mann & Cooper, c.1962. Source: archive of OMF Derek Cox Architects, Liverpool

The symbol of the lamb was frequently used: at St Charles, Kelvinside, for example, where Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s sanctuary was richly decorated in Mexican onyx and other valuable stones, its high altar incorporated a bronze sculpture of the lamb by Benno Schotz. Occasionally the pelican also appeared, a symbol of the self-sacrifice of Christ: engraved onto marble at Weightman & Bullen’s St Catherine of Siena, Lowton, for example, where photographs of the opening ceremony showed the altar in use without a frontal.31 For every case of an altar that received the liturgically correct coverings there was another whose decoration was meant to take the place of such covering. Some rules could therefore be broken, provided the general appearance of the furnishings remained familiar.

In most cases of such a decorative treatment of liturgical elements, the intention was to harmonise each feature with the architecture of the building, and architects often designed minor furnishings such as candlesticks for the same reason. By 1960, the heavy decorative altars typical of this period were questioned. Hammond argued that altars had become little more than shelves for objects and artworks; instead, he approved of the European trend for putting furnishings, including candlesticks, on the floor, leaving altars free to express their functions of sacrifice and of the ‘holy table of the eucharistic banquet’.32 NCRG members thought liturgical elements should be designed to show their functions as objects for human use and particular purposes, made evident in their outline forms rather than through applied ornament. Charles Davis elaborated on the origins of the altar in the table, the meal being the principal aspect of the Christian sacrifice in distinction to pagan sacrificial altars.33 These ideas later led to a preference for smaller altars, often explicitly referencing the table form.

For some architects, a careful study of O’Connell’s historical analysis of liturgical elements led to new forms that obeyed the letter of the rules but also attempted to recover their ancient meanings and purposes. Velarde noted that the earliest altars consisted of ‘a tomb and a mensa’ and thought that these two elements, with a minimum of decoration, were still most suitable.34 Continuing his interest in early Christian church architecture, his practice experimented with the altar form at St Theresa at Borehamwood in London. Here a pillar-style of altar had a thin table top: made only of two relatively small pieces of plain stone, lightly decorated with the symbol of the lamb, it evoked early Christian pillar altars known from Ravenna, adding the mensa to reaffirm the symbolism of the Eucharistic meal (Figure 7.15).

Gerard Goalen also used liturgical rules to create meaningful forms. At his church of the Good Shepherd in Nottingham, opened in 1964, the altar was integrated with the architecture, its unusual vaulted form following the geometry of the ceiling vaults (Figure 7.16, Plate 10). It was given a low, veiled tabernacle and six candlesticks as required, and a baldachino was suspended high above it. The communion rails were given the same distinctively vaulted form as the altar. At Harlow, Goalen had written about the relationship of these two elements: ‘The communion rail is similar in design and construction because it is, in a sense, an extension of the altar’.35 O’Connell, too, had pointed out this relationship: ‘the communion rail is really regarded as a continuation of the altar “of which we partake” … when we receive Communion as the completion of the sacrifice’, he wrote, and insisted that, like the altar, it should be covered with a linen cloth, theoretically required by the liturgy’s rubrics though rarely used in practice.36 For Goalen the communion rail became a feature that did not so much divide the congregation from the sanctuary, as was commonly thought, but could actually serve to unite them with the liturgy.

It is clear therefore that the rules of canon law were broadly upheld by parish priests, architects and dioceses in modern church architecture, generally strictly and sometimes with more licence. Altar arrangements differed little between churches, yet there was still scope for architects’ creativity. Enhancing the altar’s visual dominance aimed to concentrate attention on the liturgy, while in some cases careful thought about the rules could prompt new insights into the meanings and purposes of liturgical furnishings.

7.16 Good Shepherd, Nottingham, by Gerard Goalen, 1961–64. Stained glass by Patrick Reyntiens, © Patrick Reyntiens, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013. Photo: Henk Snoek, c.1964. Source: RIBA Library Photographs Collection

All this would suddenly change when the Second Vatican Council revised the very concept of a rule-based church architecture. Liturgical movement writers questioned rule-bound approaches not just in church architecture but in liturgy itself. Liturgy was governed by minute rules about ritual actions whose transgression might threaten the sacred effects of the ceremony.37 The architecture of the sanctuary was governed by a similar fear of failure to adhere correctly to ritual stipulations. Increasingly, however, the liturgy was desired to be a genuine communication between priest, people and God rather than a ritual. In the past, wrote one commentator, the priest ‘had “mechanised” words and gestures to be certain of not breaking the rubrics’; in the revised liturgy, he had to ‘invent authentic gestures’.38 ‘The priest has to keep constantly in mind the style of celebration that is suitable for the community over which he presides’, wrote Lancelot Sheppard. ‘There can be no rule of thumb following of the rubrics, no routine celebration.’39 The same was true of architecture: having followed and explored liturgical conventions, architects and clergy were soon to be confronted with a state of unprecedented uncertainty over liturgical design.

LITURGICAL REFORM

Throughout the period covered by this book, liturgy was reformed in a long process of which the Second Vatican Council was only one crucial stage, with continuing effects on parish church architecture. Pius XII’s reforms of the liturgy did not affect its texts so much as the way it was conducted and understood. His revisions to the Holy Week liturgies from 1951 to 1955 had an especially significant impact and some specific effects on church architecture. On Palm Sunday the congregation was urged to join in the clergy’s procession outside and into the church building. Other Easter services were simplified and their timings changed, aiming to restore them to their supposedly original times.40 With the reforms came a revival of lay interest in the Holy Week ceremonies and a surge in attendance.41

Greater attention to these ceremonies followed in church design. Weightman & Bullen were especially interested in providing processional circuits wide enough for the congregation to participate, as they did at St Ambrose in Speke. They also emphasised baptisteries in a way that was then unusual. At Speke, like several of their other churches of the period (St Mary, Leyland; St Margaret Mary, Liverpool) the baptistery was centred in a space immediately beyond the vestibule, where the Easter Vigil ceremony might be carried out in especially dignified surroundings: the fire would be lit in the porch, the paschal candle brought in procession down the nave and returned to the baptistery for the blessing of the water, when the candle was dipped into the font. The liturgy required this ceremony to be conducted in sight of the congregation whenever possible. The visual prominence of the baptistery in these churches therefore suggests they were designed with the Easter Vigil in mind, the congregation turning to witness the blessing in a space that lent it symbolic significance. Another architectural feature of Holy Week was the need for an altar of repose for temporary reservation of the Blessed Sacrament, which generally took place in a side chapel: in many churches a chapel was designated for this annual use and given a second tabernacle.

A revival of interest in the sacramental ritual of baptism was another reason for prominent baptisteries. The liturgical rubrics stipulated that the font had to be railed off, and the rite itself implied its location: it was a three-part ritual, beginning in the narthex, entering the nave of the church and proceeding to the baptistery to culminate in the pouring of water. O’Connell and many other writers thought that it was important that the baptistery floor was lower than the nave so that movement into it became an enactment of Christ’s baptism and evoked the analogy with death and resurrection made by St Paul.42 In many churches before the council, however, the baptistery was treated like another side chapel, baptism being attended only by close relatives with little ceremony: at St Joseph, Wembley, by Reynolds & Scott, for example, it originally occupied one of the side chapel spaces, stepped down and given a mosaic floor with watery symbolism; even that at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral occupied a chapel, railed off from the nave.43 Similarly, even though architect Richard O’Mahony was keenly aware of the liturgical movement, his early baptisteries were relatively insignificant: that at St Patrick in St Helens was architecturally innovative in material and detailing, but too small for use by any more than a small gathering and barely visible from the nave.

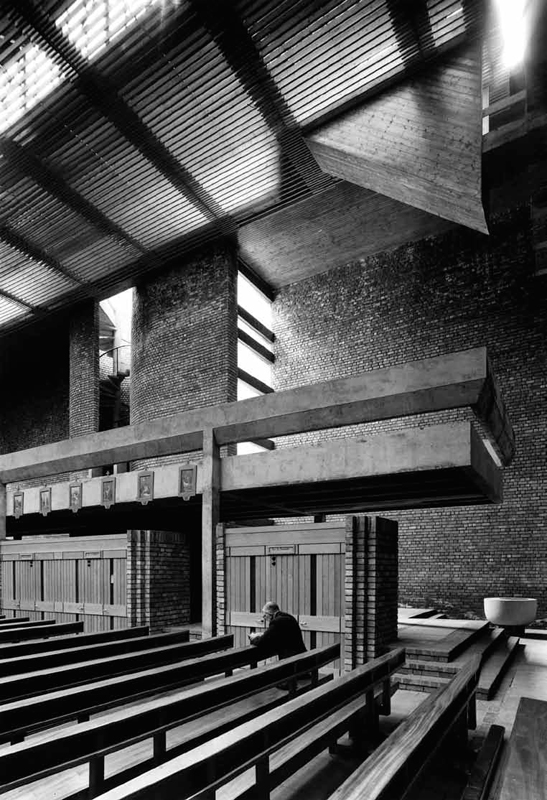

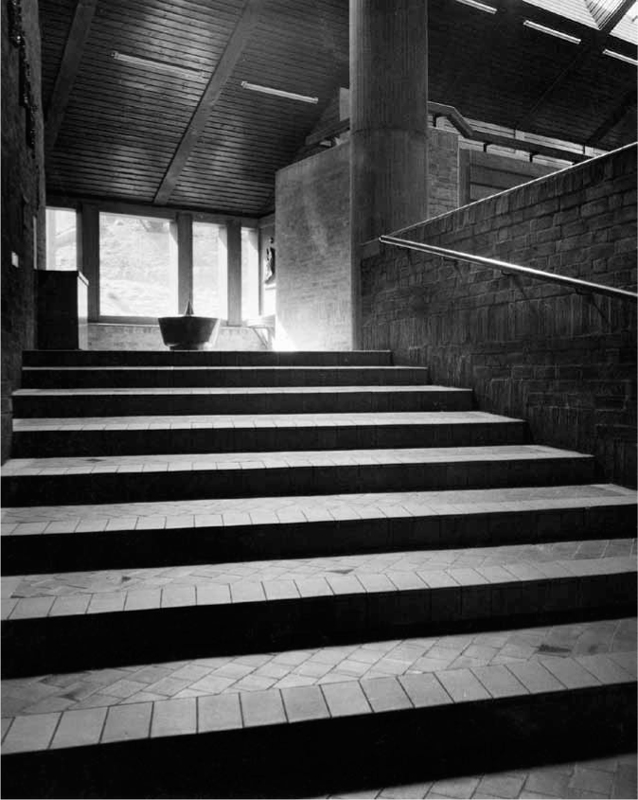

Weightman & Bullen’s churches were thus comparatively significant in their treatment of this feature. So, too, were those of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia: in their churches, the position of the font often became an anchoring point for an orchestrated entrance sequence. At St Bride, East Kilbride, worshippers entering the main door walked under the gallery, turning left to walk to the rear of the building, where the font was visible beyond the gallery, then turning right at the font and up a step before entering the nave (Figure 7.17). At Our Lady of Good Counsel in Glasgow, the door opened to a stepped ramp with the font at its summit; once reached, the nave opened up on turning to the right (7.18).44 These exceptionally well-studied entrance sequences linked the ordinary arrival of worshippers to the ritual of baptism. In the newly prominent liturgy of the Easter Vigil, they would have made the solemn entrance ritual especially dramatic, extended in time and framed within hinged strips of space.

Until the Second Vatican Council, liturgical reform proceeded with caution. In December 1963, however, the ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ was approved by the council, giving official endorsement to the liturgical movement and prompting major reforms. The principle of ‘active participation’ was amplified into an urgent imperative: ‘In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy the full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else, for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit.’45 To achieve this it announced that the liturgy was going to be reformed. New church architecture, it said, had to be ‘suitable for the celebration of liturgical services and for the active participation of the faithful’. Not only would liturgy be revised, but so would the rules on church architecture and furnishing: ‘Laws which seem less suited to the reformed liturgy should be amended or abolished. Those which are helpful are to be retained, or introduced if lacking.’46 Far-reaching change was anticipated in both liturgy and the requirements of church architecture.

The following year the Vatican issued the document ‘On Implementing the Constitution on Liturgy’. Its chapter ‘On Building Churches and Altars for Active Participation’ insisted that this principle be used to plan new churches. This document now permitted Mass to be celebrated facing the people, and altars had to be made suitable for it if necessary. The tabernacle therefore had to be small, but, with the approval of the bishop, the Blessed Sacrament could now be reserved in another part of the church ‘provided it is really dignified and properly ornamented’.47 Crucifix and candles could, if the local bishop approved, be placed alongside the altar. The celebrant now had to have a seat that indicated his role of ‘presiding over the assembly’.48 Side altars were to be few in number and set away from the sanctuary. The choir had to be positioned so that it was part of the congregation, suggesting that galleries were no longer desirable.49 The document implied that a new form of church architecture was now required. A few years later the Vatican’s ‘Instruction on the Worship of the Eucharistic Mystery’ added a new emphasis on the unity of the faithful at the Mass: ‘In the celebration of the eucharist’, it said, ‘a sense of community should be fostered so that all will feel united with their brothers and sisters in the communion of the local and universal Church and even in a certain way with all humanity’.50 It was a passage that would be imaginatively heeded by architects and clergy, and applied not just to furnishings but to churches as a whole.

7.17 St Bride, East Kilbride, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1957–64. View of rear of nave showing font. Photo: Sam Lambert, c.1964. Source: Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Library Photographs Collection

7.18 Our Lady of Good Counsel, Dennistoun, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1962–65. View from entrance towards font. Photo: Studio Brett, c.1965. Source: RIBA Library Photographs Collection

Meanwhile, canon law relating to church buildings was effectively suspended, causing great uncertainty. Many churches were designed before the ‘Constitution on the Liturgy’ and completed after it, and many more were still being designed during this crucial period. Liturgical reform followed only slowly: English was permitted incrementally in the Mass, the Eucharistic canon remaining in Latin, until the new rite was eventually approved and made compulsory in 1969. In the meantime, further documents were issued by the Vatican and by national hierarchies of bishops concerning church architecture and furnishing, while the rubrics of the Missal underwent continual adjustment. The uncertainty of this period gave increasing freedom of experimentation to architects and clergy until the new rite was adopted.

The location of the tabernacle was one of the most contested problems of the liturgical reforms, touching a central point of Roman Catholic belief and practice, the doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the consecrated host that was maintained by Catholics as a defining feature of their faith, enacted through devotional practices. In 1967, the ‘Instruction on the Worship of the Eucharistic Mystery’ advised clergy to place the tabernacle in a chapel away from the main altar.51 If retained in the sanctuary, the tabernacle now required a special arrangement apart from the altar.52 Instead of clarifying the Vatican’s position, however, this document created further uncertainty and unease over the apparent demotion of the Blessed Sacrament from its position of prominence. Architects and clergy often remained cautious. Archbishop Gray, for example, wrote to his finance secretary, ‘I do feel that even if we have a Blessed Sacrament Chapel it should be in such a position that the Tabernacle can be seen from the main Church. … The presence of the Blessed Sacrament largely accounts for the wonderful reverence with which people treat our Churches.’53

These concerns were negotiated in the sanctuaries of churches. Before Mass facing the people was permitted in 1964, architects and clergy sought altar designs that would allow Mass facing in either direction, uncertain of the future. As early as 1958, O’Connell had recommended a double altar, stepped down at the front: a celebrant behind it would stand at a higher level and celebrate across the altar, while the tabernacle was fixed at the lower level, where Mass could be said facing away from the people if required. It would prevent the tabernacle from obstructing the celebrant when it was retained on the altar as the Vatican at first insisted.54 One such altar was built for the church of St Andrew in Dumfries in 1964 by local architects Sutherland, Dickie & Partners, to great interest from the Catholic press.55 Sometimes a new altar was added close to the nave, effected at Westminster Cathedral in 1965, where the original high altar remained intact, and in the new church of St Teresa of Avila at St Helens, where the tabernacle was placed on a shallow gradine at the back of the sanctuary, as if the altar had been split into two parts, the archdiocese having ruled out a second altar.56 This arrangement was considered unsatisfactory by many writers, as it suggested there were two high altars in the church. O’Connell also thought it ‘unbecoming’ for the priest to stand with his back to the Blessed Sacrament.57 One solution was to raise the tabernacle over the head height of the celebrant; or, as at John Newton’s church of St Aloysius at Somers Town in London, to place the tabernacle on one side of the sanctuary in a specially decorated shrine.

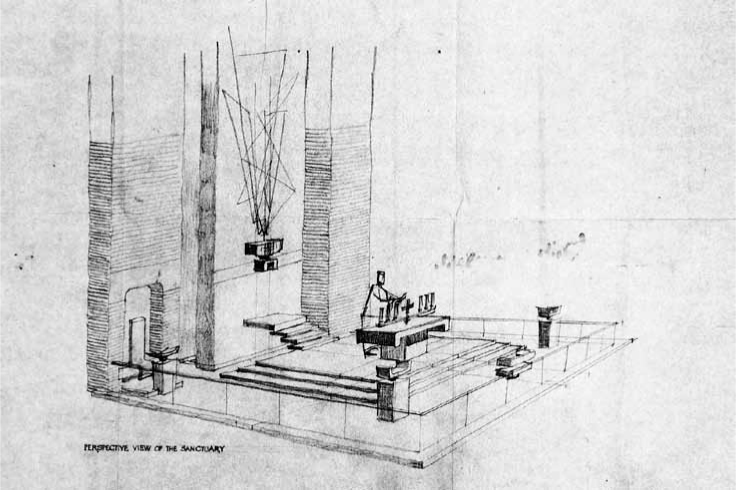

Negotiations over church design could often be lengthy. At Our Lady Help of Christians at Tile Cross in Birmingham, Richard Gilbert Scott tried out different arrangements, submitting sketches to the Archdiocese of Birmingham. His first designs for the church in 1964 showed a T-shaped plan like that of Our Lady of Fatima in Harlow with the tabernacle on the altar. In 1965 he submitted a proposal for a double altar like that at Dumfries (Figure 7.19). To this the diocese responded that it was ‘undignified’. Scott’s proposal for a celebrant’s seat on a platform behind the altar was also questioned, as it was thought to be too much like a bishop’s throne. Scott drew a new sanctuary layout the following month, the tabernacle high on the wall so that it was over the celebrant’s head, reached by cantilevered steps, and a chair in a niche to the left (Figure 7.20). Two ambos were now added at the front of the sanctuary.58 The seat was still thought too prominent: a temporary and movable one was requested instead; and Scott was asked to move the ambos back to address the transepts.59 As completed in 1967, the sanctuary was a single composition in white marble under the soaring concrete tower, the tabernacle placed on axis on a pedestal at the rear, the ambos built in beside it, and the chair made of wood (Figure 7.21). Like many other architects building churches in the mid-1960s, Scott had to counter the clergy’s uncertainty with coherent ideas of his own.

Richard O’Mahony, meanwhile, solved the Vatican’s preference for separating Eucharistic reservation from the Mass with a unique idea: a sliding screen across a Blessed Sacrament chapel located behind the sanctuary. At St Patrick in St Helens, the Archdiocese of Liverpool permitted this arrangement in 1964.60 The tabernacle was contained in its own chapel, its seating concealed behind the sanctuary wall; a large opening on one side made the tabernacle visible to the nave. During the Mass, the screen was drawn across. On it was a fibreglass sculpture of the Resurrection by artist Norman Dilworth, intended as a complement to the Stations of the Cross and to the same artist’s altar crucifix. O’Mahony wrote that this arrangement was especially significant for the Easter liturgy: the screen would be drawn across at midnight when the Easter Vigil Mass began, revealing the image of the Resurrection.61 O’Mahony obtained permission for the same layout at a church in the diocese of Shrewsbury: St Michael and All Angels at Woodchurch was already under construction when it was revised to adopt this layout, the screen being installed some time after its opening in 1965 (Plan 4c).62 Reviewing the church, a writer in the Clergy Review approved the arrangement and recommended it to others, though it never caught on.63

Many of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s Catholic churches were built during this period of transition, before the new liturgy was published. Our Lady of Good Counsel at Dennistoun in Glasgow was designed in 1962 and completed in 1965, its liturgical arrangements modified during construction (Figure 7.22). The position of the altar and the shape of the predella were changed late in 1964 for Mass facing the people.64 The side chapel became a Blessed Sacrament chapel, and the candlesticks were redesigned to be placed on the steps beside the altar.65 The celebrant’s chair was placed under a tall free-standing crucifix, and an ambo was built within the sanctuary, giving different locations for each part of the Mass.66 At St Benedict in Drumchapel, Glasgow, with a C-shaped seating plan on a diagonally oriented square, several proposals were made for the tabernacle: one placed it against a supporting pillar at one side of the sanctuary, and the final layout incorporated it into a low brick screen at the rear, where it could also be seen from a chapel behind.67 Slow progress on the building site allowed time to adjust the interior before the church was opened in 1970, when the new liturgy was fully in use. By now, Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s response to the liturgical movement made their churches increasingly adaptable to new liturgical practices with relatively small modifications.

7.19 Our Lady Help of Christians, Tile Cross, Birmingham, by Sir Giles Scott, Son & Partner, 1962–67. Sketch proposals by Richard Gilbert Scott for a double altar, 1965. Source: Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Birmingham. Courtesy of Richard Gilbert Scott

7.20 Our Lady Help of Christians, Tile Cross, Birmingham, by Sir Giles Scott, Son & Partner, 1962–67. Sketch proposals by Richard Gilbert Scott for sanctuary arrangement, 1965. Source: Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Birmingham. Courtesy of Richard Gilbert Scott

7.21 Our Lady Help of Christians, Tile Cross, Birmingham, by Sir Giles Scott, Son & Partner, 1962–67. View from transept: stained glass by John Chrestien. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

7.22 Our Lady of Good Counsel, Dennistoun, Glasgow, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1962–65. Photo: Studio Brett, c.1965. Source: RIBA Library Photographs Collection

At Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, indecision over liturgical arrangements during the Second Vatican Council resulted in Gibberd’s iconic structure housing relatively informal furnishings. When Gibberd and his assistant Jack Forrest asked about the design of the high altar, proposing a single large block of marble, the cathedral committee deliberated and disagreed over the form the altar should take, acknowledging that the matter was currently in a ‘state of flux’. They passed on to Gibberd the rules of canon law: ‘the Altar should consist of one piece of solid stone table or mensa with a support or supports’, they wrote, noting that the altar would in any case be covered with frontals.68 Gibberd retained his solid block, which he had already ordered, but raised it on a platform. In 1964, after the ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ had announced the suspension of canon law but before any further documents had been published on the subject, the detailed design of the side chapels became urgent. The Blessed Sacrament chapel, it was decided, would be designed for Mass facing away from the people, and the Lady chapel for Mass facing towards them.69 A year later, however, it was clear that the Blessed Sacrament chapel would have to be redesigned to allow Mass facing the people, and hasty revisions were made.70 Gibberd had pressed hard for a decision to avoid temporary furnishings being used in this chapel, something he thought would be ‘visually disastrous’.71 As Paul Walker argues, the indecision of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral’s clergy at a time of suddenly shifting liturgical practices led to a building with a contradictory interior. Some elements were fixed and monumental; others were temporary and movable: the archbishop’s throne and canons’ stalls were of timber; most of the side chapels had temporary altars; and there was no permanent lectern or ambo.72 On a lesser scale, such problems resulting from the Second Vatican Council were felt by Catholic church architects and clergy engaged in church projects all over Britain.

Separate Blessed Sacrament chapels, always a feature of cathedrals, began to become common for parish churches. John Newton’s church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary at Hayes had included one as early as 1962, probably adapting a chapel during construction, placed prominently at the head of an aisle and decorated with stained glass containing Eucharistic symbols. In 1964, Newton included such a chapel in his design for St Anselm in Southall, London, a large fan-shaped church clearly inspired by the ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’, opened in 1968, the tabernacle placed on a pedestal behind an altar at the head of an aisle.73 At St Aidan, Coulsdon in south London, Newton rebuilt an incomplete pre-war church by Adrian Gilbert Scott when a new parish priest, Kenneth Allan, requested a church that addressed ‘the Liturgical thinking of our times’, and while keeping some of Scott’s shell, he created an entirely new plan, roughly a square with seating on three sides of the altar and a separate Blessed Sacrament chapel on one side (Figure 7.23).74 The Blessed Sacrament chapel was this church’s only separate space for devotion.

Looking at this period of transition, it is, perhaps unfairly, easier to locate and examine the sites of progress and reform than it is to acknowledge the sites of resistance to change. In reality reform occurred slowly and unevenly. When Archbishop Beck established a Liturgy Commission at Liverpool in 1968, its members realised that the diocese did not know what liturgical practices were actually in place in its parishes and undertook a survey. Of 102 parishes, only 64 had Mass facing the people; only 39 had any music at Mass on Sunday and, of those, few had congregational singing; only 41 had lay readers, seen as an index of congregational participation.75 The 1960s was a decade of increasing diversity in religious practice: just as new churches were being built that embodied liturgical movement concepts of worship, older churches continued to be used in much the same way as before.76 This situation began to change in 1970, when the new rite of Mass was made compulsory.

7.23 St Aidan, Coulsdon, London, by Burles, Newton & Partners, 1966. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

THE NEW LITURGY: ACTION AND INTIMACY

The new rite of Mass not only used the local language throughout, it included many new actions, drastically simplified the liturgy and changed its emphasis and meanings. Lay readers, encouraged in earlier reforms, were now expected to read the two Epistles. An offertory procession, derived from early Christian liturgy, further required the physical participation of the faithful: members of the congregation brought the bread and wine from the back of the church to the celebrant. The laity also now read ‘bidding prayers’ before the canon. The Mass took place in full dialogue between priest and people, and the canon was said aloud. The new rite took many of its forms from the former high Mass, which had only rarely been celebrated before, including ceremonial movement around the sanctuary between chair, ambo and altar, in contrast to the more customary low Mass largely conducted at the altar. Only one ambo was now required, from where the readings and sermon (now called the ‘homily’) were to be given as part of the liturgy. Several elements were left to local hierarchies to define: so, for example, the British hierarchies decided that communion would normally be received standing rather than kneeling, and the ‘kiss of peace’ that in a high Mass had been a ritualised gesture between the clergy in the sanctuary became an exchange of handshakes amongst the laity.

The intentions of the new rite were declared in its preface and rubrics, the ‘General Instruction on the Roman Missal’. The instruction began by defining the centrality of the liturgy, incorporating the role of the faithful into its first statement about liturgical worship: ‘The celebration of the Mass, as an action of Christ and the people of God hierarchically ordered, is the centre of the whole Christian life.’77 This was already a spatial statement – celebrant and congregation formed one ‘people’ in a hierarchical distribution; and more followed. The instruction required an expressive zoning of the interior by function: ‘the shape of the church ought in some way to suggest the form of the assembly and the different functions of its members’, it advised, while at the same time ‘they should also bring everyone together in a way which shows that the Church is one’.78 Audibility was emphasised. The ambo and the liturgy of the word were given considerable significance: ‘the table of God’s word and the table of Christ’s Body’ formed the two main foci of the Mass, as Christ became present through scripture in a manner related to his sacramental presence in the Eucharist.79 Whereas the rubrics on liturgical furnishings had previously been prescriptive laws about form, the new rubrics were more informal and encouraged diversity: conventional materials for furnishings could be substituted with others relevant to the local context. The capacity of church buildings and liturgical objects to convey meaning was now viewed as contingent on culture and on their reception by the laity.

This was a different conception of liturgy to that prevailing before the council. Commentators felt that the Mass would no longer be as fixed as it had been: ‘The whole spirit abroad in the Church … is quite opposed to the mentality that would seek to impose a rigid uniformity of eucharistic celebration on all for a long time to come’, wrote Sheppard.80 Experimentation and change were seen as inevitable after a decade of transformation. The participation of the faithful was seen as crucial for the effectiveness of liturgy. The prayerful silence of the preconciliar liturgy would give way to a liturgy of acclamation and action, as, it was claimed, had been its original mode of performance.81 The church architecture that would make possible this new kind of liturgy had been set out by the Catholic hierarchy of England and Wales the previous year in a booklet of 1968, the Pastoral Directory for Church Building. It endorsed recent developments in church architecture, virtually insisting on new plan types: the ‘assembly of the faithful should embrace the sanctuary’, it said; and it even instructed architects on a design method for liturgical architecture: ‘It is of first importance to locate in the sanctuary the centres of action in their ordering of priority and to consider the movements of all in the sanctuary’; the congregational seating plan would follow logically, and furnishings ‘should be integrated with the architectural concept of the whole building’. The congregation had to be able to see, hear and join in worship with the celebrant.82

Ideas about the rite of baptism also changed: while the liturgical movement led to a renewed emphasis on baptisteries, later reforms made baptism more liturgical by assuming a witnessing congregation, symbolising the incorporation of the individual into the Church represented by the gathered parish. The ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ had already hinted that baptism would be integrated into the Mass. By the mid-1960s, even churches by O’Mahony, Goalen and Winkley were criticised for having separate baptisteries ill-suited to congregational celebration.83 A new, simplified rite of baptism was published in 1969, making it a more public event. The baptistery now had to be capable of holding a congregation or to be ‘in clear view of the faithful’, and if that was not possible baptism was to be performed outside it in a more suitable location.84 Fonts were therefore increasingly placed near the sanctuary. At St Michael in Wolverhampton, Desmond Williams placed the font here as early as 1968 to emphasise ‘“reception” rather than entry into the church and … for occasional public baptisms’ (Figure 7.24).85 Nevertheless the desire for a symbolic place near the entrance remained. Winkley resolved this tension at St Elphege at Wallington by siting the entrance near the sanctuary at the front of the church in view of the congregation, the font placed beside the entrance on an extended sanctuary platform (Figure 7.25).86

As the new decade approached, modern church architecture settled into established forms. Square and oval plans with curved seating around an open sanctuary with the altar placed well forward became the norm. Side chapels were few and often contained the tabernacle. Churches also became smaller, not only because of dwindling congregations and decreasing funds but also because it was felt that large churches were unable to provide the level of intimacy that the new liturgy demanded. Altars also became lower, smaller and simpler. Candlesticks became small and unobtrusive, and decorative cloth hangings were often dispensed with in favour of a single white cloth. The ambo and celebrant’s chair had to be specially designed and related to everything else. Amongst typical churches of this period was St Thérèse of Lisieux at Sandfields, Port Talbot, by F. R. Bates, Son & Price, designed around 1969 (Figure 7.26).87 The plan was a semicircle, and the sanctuary was a lobe-shaped platform of green marble, its material distinguishing it as a separate space as required by the ‘General Instruction on the Roman Missal’. Ambo and altar were of the same material, linking them as the primary liturgical centres, while the celebrant’s chair was of wood so its position could be changed. The tabernacle was originally placed in a chapel to the left of the sanctuary. Other side chapels were placed behind the congregation so that they were not visible during the Mass. Overhead, reinforced concrete folded vaults splayed out from the sanctuary to express the unity of the congregation.

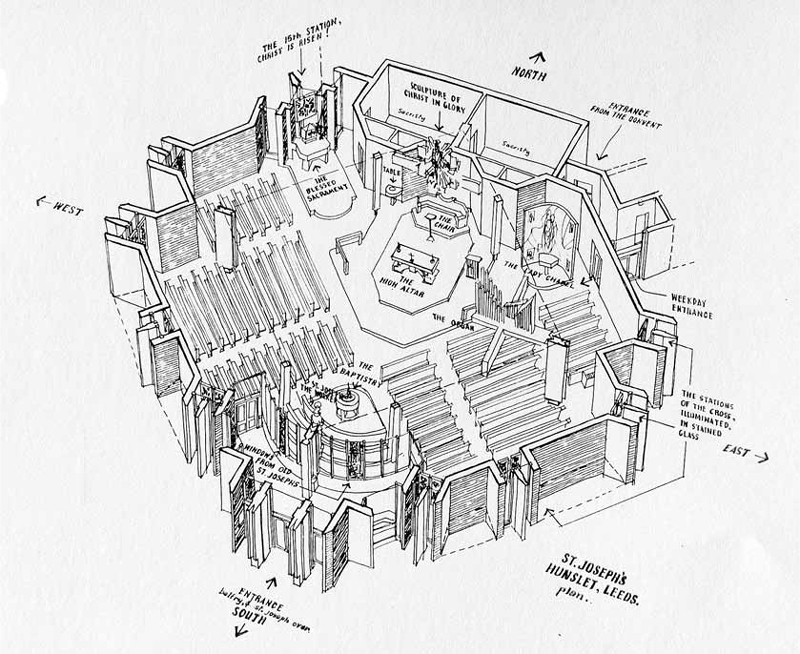

Circular churches continued to be built but became more carefully considered in terms of liturgical function after the criticisms of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. The church of Corpus Christi at Stechford in Birmingham by Ivor Day & O’Brien had a central altar, but it occupied a sanctuary that extended to the rear like a thrust stage, backed by a plain brick reredos with the tabernacle on a pillar.88 The congregation was arranged in a horseshoe shape; the altar was small, and there were no communion rails. A pine-boarded ceiling and corona emphasised the unity of the interior. The square plan on a diagonal axis was more commonly used for new churches in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with many possibilities for detailing and liturgical arrangement. At Cantley in Doncaster, John Black designed a small square church on this plan, castle-like on the outside, intimate inside, its simple table altar at the front of the sanctuary and the tabernacle a decorated aumbry in a side wall.89 The Bradford father-and-son firm of Langtry-Langton favoured this plan type, building it at large and small scales. St Peter-in-Chains, Doncaster, was a big town-centre church designed by J. H. Langtry-Langton, planned around a geometry of two overlapping angled squares: ‘An ideal grouping was … drawn at the sketch plan stage, and when this had been achieved, a geometric structure was transposed over it’, claimed the architect.90 St Joseph at Hunslet in Leeds by Langtry-Langton’s son Peter was a variant on the diagonal square plan whose motivating factor, he argued, was the centrality and closeness of the altar amidst the congregation (Figure 7.27). The celebrant’s chair occupied a special platform linked to the sanctuary. The tabernacle was set in a niche at one side in an arrangement that the bishop of Leeds, William Wheeler, thought was an ‘ideal placing … giving it a position of the highest dignity and availability’.91 The altar was made of plain Yorkshire stone in a departure from conventional decorative materials to relate this church to its locality. Even smaller was Langtry-Langton’s rural church of St Margaret Clitherow at Threshfield, a pyramidal tent-like building with two small groups of curved pews close to a small, rubble-stone altar.

7.24 St Michael, Wolverhampton, by Desmond Williams, 1965–67. The liturgical furnishings, including font, are mostly original: reredos, tabernacle, candlesticks, altar and font inserts by Robert Brumby. By permission of Robert Brumby. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

7.25 St Elphege, Wallington, London, by Williams & Winkley, 1969–72. The font is visible beyond the altar, next to the main entrance door. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

7.26 St Thérèse, Port Talbot, by F. R. Bates, Son & Price, c.1969. The tabernacle was originally housed in a chapel to the left of the sanctuary. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2012

In London, the churches of Our Lady and St Peter in Wimbledon and St Paul, Wood Green, made similar uses of the angled square plan with a monumental employment of brick and reinforced concrete. In Wimbledon, Tomei, Mackley & Pound’s design was capped with a pyramidal roof and bright lantern over a high central space and lower secondary seating areas (Figure 7.28). At Wood Green, much the same plan was given brutalist expression by John Rochford & Partners with a reinforced concrete grid in-filled with brick inspired by Schwarz’s churches of the 1950s (Plate 11). A deep concrete beam over the sanctuary concealed a lantern that washed light over it, defining the sanctuary without dividing it from the nave, the altar and ambo projecting out beyond it. In both these churches the tabernacle was placed in a chapel to one side of the sanctuary where it could be accessed by the celebrant while giving a place for devotion outside the liturgy. In Glasgow around the same time, Gillespie, Kidd & Coia used the diagonal square plan that they had previously employed at Cumbernauld for their only Catholic church designed specifically for the new liturgy, St Margaret in Clydebank (Plan 2d). Here, raked seating descended to a broad sanctuary with the liturgical elements arrayed in a sculptural composition around the altar. Rippling walls of brick and a red-painted steel space-frame roof embraced sanctuary and nave in an expression of unity. By the end of the decade, architects and clergy had reached a consensus on the forms and principles of church design and on the theological ideas they wished to convey.

These churches could nevertheless be seen as ultimately conventional in their concept of the liturgy. Their liturgical arrangements were generally fixed in permanent materials, despite expectations of further changes to come. Their architects and clergy retained a pre-conciliar idea of the church as a monumental and devotional sacred space for ritual, even if the ritual of the Mass was now no longer the performance of a single celebrant but the action of a community. An alternative approach already becoming significant in the 1960s was to accept instability and intimacy in worship as new conditions of the Church, embedding these qualities into church design. Flexible churches, with moving partitions and furnishings, previously only considered temporary, started to become theologically and architecturally appealing in their own right, offering spaces that could be adapted for future changes and for different congregations. In the 1970s, Winkley argued that churches should be small and that the fixed arrangements of the previous decade were a hindrance: ‘Our intention now should be to develop freer plan arrangements where people can move, see and be seen’, he wrote, adding that the use of chairs rather than pews would assist such movement.92 A new and further reform of church architecture was now being suggested that addressed the fundamental principles of what a church was, not just its liturgical layout – a reform that will be considered in more detail in the final chapter.

7.27 St Joseph, Hunslet, by J. H. Langtry-Langton & Partners, 1968–71. Diagram of plan by Peter Langtry-Langton, c.1971. By permission of Peter Langtry-Langton. Source: souvenir booklet accompanying church opening, 1971, Leeds Diocesan Archives

7.28 Our Lady and St Peter, Wimbledon, London, by Tomei, Mackley & Pound, 1970–73. The tabernacle was originally placed in the chapel to the right of the sanctuary. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

One such experimental church had a particular significance in relation to liturgical development in Britain. The church and pastoral centre of St Thomas More at Manor House in London was always much more than a parish church: its parish priest, Harold Winstone, established a Centre for Pastoral Liturgy for the Archdiocese of Westminster there in 1969. Winstone wrote widely about liturgy, becoming involved in the Liturgy Commission for England and Wales under Archbishop Grimshaw of Birmingham from 1963. The centre at Manor House was intended as an educational and experimental facility for the liturgy, including the creation of national publications and demonstrating liturgical forms, particularly new music, to others. It was the first church in the Archdiocese of Westminster to implement new rites as they were published and tested new translations, rites and music.93 John Newton, its architect, became a member of the Liturgical Commission of the archdiocese which oversaw the centre’s activities.94

Built around 1974, St Thomas More occupied a small site in a street of Victorian terraced housing and was domestic in appearance. On the ground floor was a social hall and offices for the liturgical centre; above was the church (reminiscent of the ‘upper room’ of the Last Supper), its sanctuary in a cantilever; on top were flats for Winstone and his assistant. The presence of Catholic West Indians in the parish was a pretext for Winstone to experiment with adapting the liturgy to their needs through ‘spontaneous forms of worship’.95 Accordingly the space of the church was flexible, with sliding partitions that could be drawn across secondary spaces to unify the nave or divide it into more intimate areas (Figure 7.29). The liturgical furnishings were made of timber, including the altar and tabernacle stand, so that the space could be reconfigured whenever desired.96 The building was designed to accommodate experiment and continual change in liturgy, as well as to minimise effects of ritual by reducing any appearance of formality or artificiality, hoping thereby to engage the congregation more effectively in the liturgical celebration.

7.29 St Thomas More, Manor House, London, by Burles, Newton & Partners, c.1974. View of the chapel. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

The process of reform in liturgy and church architecture from the 1950s to the 1970s was complex and often fragmented. While the shape of the church building changed dramatically across this relatively brief period, ideas about its liturgical function and actual liturgical practices shifted at different rates: architecture and religion had parallel trajectories, but different speeds and changes of gear. Yet Roman Catholicism in this period was even more complex than this focus on liturgy would suggest. The NCRG and the liturgical movement before it argued for a primary focus on the Eucharist, and were also concerned with the sacraments, especially baptism; but this emphasis shifted attention from an area of religious practice that remained of great importance in Roman Catholic culture, namely non-liturgical devotions. Popular devotions of all kinds were significant in Roman Catholic religious practice in Britain throughout this period, and, as I will show in the next chapter, were often given special prominence in new church buildings, despite and alongside liturgical reform. However important in both architectural and religious narratives of this period, therefore, liturgical reform must be seen as one amongst many other factors behind the Church’s making of itself through architecture.

NOTES

1 Crichton, ‘The Liturgical Movement from 1940 to Vatican II’, 68; Walker, ‘Developments in Catholic Churchbuilding’, 61 n. 47; Lancelot C. Sheppard, letter to the editor, The Tablet (16 Mar. 1957), 258.

2 J. B. O’Connell, ‘The New Instruction of the Congregation of Rites’, 97–8; press reports suggest its novelty (for example Mary Crozier, ‘A Dialogue Mass’, The Tablet [14 Mar. 1958], 249).

3 ‘Dunbar Church Re-Opened’, St Andrew Annual: The Catholic Church in Scotland (1960–61), 56.

4 P. G. Walsh, letter to the editor, The Tablet (10 Nov. 1962), 1084.

5 Photograph (parish archive).

6 Leo XIII, ‘On the Recitation of the Rosary’ (1884), art. 4, http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/leo_xiii/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_30081884_superiore-anno_en.html (accessed 10 Aug. 2012); James R. Reynolds, letter to the editor, The Tablet (15 Oct. 1955), 379; H. E. Calman, letter to the editor, The Tablet (22 Oct. 1955), 410; Terence J. Howes, letter to the editor, The Tablet (29 Oct. 1955), 438; R. G. Webb, letter to the editor, The Tablet (12 Nov. 1955), 486; see also J. B. O’Connell, ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 45 (1960), 300–301. A further article by O’Connell suggests it was current in Liverpool in 1962 (J. B. O’Connell and L. L. McReavy, ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 47 [1962], 497–8).

7 A. M. Wood, letter to the editor, The Tablet (29 Sept. 1962), 915.

8 John Rex and Robert Moore, Race, Community, and Conflict: A Study of Sparkbrook (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), 175.

9 CBRN (1957), 98–100.

10 It was praised, for example, in Hammond, Liturgy and Architecture, 105.

11 Mills and Lockett, ‘Plans of Churches Here and Abroad’, 13.

12 Solemn Opening: St Bride’s Church, East Kilbride [souvenir brochure] (East Kilbride: n.p., 1964) (GRCAA, Y/15).

13 ‘St Bride’s: An Appraisal’, RIBA Journal (Apr. 1966), 170–79 (172, 179).

14 Isi Metzstein (Gillespie, Kidd & Coia) to J. M. Richards (editor, Architectural Review) (23 June 1965) (GSAA, GKC/CEK/1/7); see also Proctor, ‘Churches for a Changing Liturgy’, 305–6.

15 Proctor, ‘Churches for a Changing Liturgy’, 311–12.

16 CBRN (1967), 48.

17 Watters, Cardross.

18 William Godfrey, foreword to CBRS (1960), 33.

19 John Newton, ‘The Catholic Church, Hampton Hill’, in St Francis de Sales, Hampton Hill, Middlesex: Souvenir Brochure (London: n. p., 1964), 7 (parish archive).

20 Parishioners [sic], ‘Our Church’, in St Francis de Sales, 7 (parish archive).

21 See esp. Kieckhefer, Theology in Stone, 18.

22 Rykwert, ‘Passé recent et problèmes actuels’, 297.

23 O’Connell, Church Building, 129–203 (202).

24 J. B. O’Connell, ‘The Care of the Blessed Sacrament’, Clergy Review 43 (1958), 11–18 (17).

25 Anthony Flynn (parish priest, St Mary and the Angels, Camelon) to Jack Coia (Gillespie, Kidd & Coia) (4 Dec. 1960) (GSAA, GKC/CCF/1/7).

26 Pierce Grace (parish priest, St Paul, Glenrothes) to Gordon Gray (archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh) (24 Jan. 1958); Gray to Grace (4 Feb. 1958) (SCA, DE/59/202).

27 A. Rivers (financial secretary, Archdiocese of Westminster) to David Stokes (11 Aug. 1959) (WDA, Go/2/132).

28 Minutes of meetings of the Sites and Buildings Commission, Archdiocese of Liverpool (16 Dec. 1958; 19 July 1960) (LRCAA, Finance Collection, 12/S3/III).

29 CBRS (1960), 54; (1961), 63–5.

30 CBRN (1961), 120.

31 Parish archive.

32 Hammond, Liturgy and Architecture, 38–9.

33 Charles Davis, ‘The Christian Altar’, in Lockett (ed.), Modern Architectural Setting, 13–31.

34 Velarde and Velarde, ‘Modern Church Architecture’, 519.

35 Gerard Goalen, ‘A Place for the Celebration of Mass’, in Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow: Opening Souvenir Booklet (Harlow: n.p., 1960), 38 (BDA, I3).

36 J. B. O’Connell, ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 41 (1956), 304.

37 Kieran Flanagan, Sociology and Liturgy: Re-Presentations of the Holy (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991), 150–85.

38 Llewellyn, ‘The Congregation Shares in the Prayer of the President’, 104–5.

39 Lancelot Sheppard, ‘The New “Ordo Missae”’, in id. (ed.), New Liturgy, 37.