5

Modern Church Art

Just as the Roman Catholic Church saw the adoption of a modern municipal architecture as a way to claim an accepted position within British society, the commissioning of modern art for churches could also contribute to achieving a higher social and political status. Art and architecture that adhered to mainstream British culture represented cultural capital, an investment that could repay the Church through an increasing recognition in society of its importance and legitimacy.1 Acquiring cultural capital for conversion into social capital could be particularly urgent for a Church that historically had a marginal status in Britain and a high proportion of whose members were of Irish descent. Modern architects, too, wished to incorporate art in their churches. Yet the Church would only adopt modern art on its own terms, not least because church art had to be functional, satisfying the needs of devotion and liturgical use. Artists therefore also contributed to the production of the church in partnership with architects and clergy.

The patronage of modern artists was an important aspect of modernist architectural culture in this period, even in the service of the post-war welfare state. The use of fine art, and particularly high modernist art, in a public context for such buildings as schools, theatres and civic centres was espoused by architects such as J. M. Richards of the Architectural Review and much debated. It was a persistent theme at the CIAM meeting of 1951 in Hoddesdon entitled ‘The Heart of the City’, whose delegates visited the Festival of Britain, its South Bank site the subject of a comprehensive programme of artistic installations.2 There had already been discussion of the need for the ‘emotions’ of the people to be considered in modern architecture and the role that artists could play in fulfilling this spiritual need.3 It was an argument that was especially allied to the New Empiricism and was sometimes contentious within modern movement discourse. Modern architects in Britain, however, often coming from a background in Arts and Crafts design, frequently took an unproblematic approach to working with modern artists, who welcomed opportunities for collaboration. A pioneering venture in involving artists with architectural projects was established by the London County Council, which, in 1954, decided it had a social duty to provide modern art to the masses and allocated an annual budget for artworks to be provided for new schools and housing estates. Two young artists, Antony Holloway and William Mitchell, were employed to produce art for new public buildings, working with architect Oliver Cox at the Council’s Architects’ Department. It was an important model for the integration of art and architecture, and Mitchell would later undertake significant Catholic commissions in a similar vein at Liverpool and Clifton cathedrals.4 The Arts Council, established on a permanent basis in 1946 to dispense funding to arts organisations and local authorities, was likewise a product of the post-war welfare state’s desire to make high culture accessible to the masses.5 The provision of modern public art was seen as an intrinsic duty of the new socially concerned state: modern architects willingly concurred, and the Church shared in this climate of cultural benevolence.

ART AND THE CHURCH

In church architecture, of course, art had well-established historical precedents. The churches at Assy and Audincourt in France were influential models for a modern approach to integrating church art and architecture. Both were simple basilican buildings designed by Maurice Novarina. At Assy, Couturier invited the best modern artists regardless of their faith to create works of varying degrees of abstraction: Henri Matisse produced an image of St Dominic that was a faceless linear design on ceramic tiles; André Lurçat designed a tapestry depicting the Apocalypse to hang within the apse; Jewish artists Jacques Lipchitz and Marc Chagall were commissioned for further pieces in the 1950s.6 Couturier and his colleagues at L’Art sacré followed Maritain in believing that the artist had to take a spiritual stance in devotional art, but thought that the artist’s creative intelligence and willingness to adopt a Christian attitude were more important than their adherence to religious duties.7 Furthermore, Couturier argued that it was the artist’s accomplished ability to convey a spiritual message through formal composition that made religious art devotional rather than its literal content, opening the way to non-realistic and non-figurative approaches.8 Good modern art was therefore to be preferred to the conventional realism of most pious imagery.

The arguments were controversial and evoked a response from the Vatican. Pius XII’s encyclical Musicae sacrae disciplina, on sacred music, of 1955 criticised the employment of non-Catholic artists in the Church and insisted that artists had to meet the Church’s own expectations, not just the hermetic methods of art.9 The Church’s position on abstraction was more ambivalent: it could be accepted when it might be considered decorative, especially for stained glass, which contributed to a religious atmosphere rather than being an object of prayer; but it was less acceptable for images purporting to represent Christ or the saints, when the Church’s prohibition of distortion applied.10 Abstraction was especially condemned for the sanctuary crucifix, an object of devotion within the liturgy that represented the Incarnation – Christ in the form of a man.11

On the other hand, mass-produced art had long been forbidden from churches by canon law, though the rule was widely ignored. Even the most stereotyped images were frequently therefore hand-made, parishes often purchasing them from craft producers such as Stüflesser in the Italian Tyrol, a firm that specialised in a rococo style of painted wooden statuary and that was endorsed by the Vatican.12 The 1952 ‘Instruction on Sacred Art’ went further than canon law, however, also forbidding ‘second rate and stereotyped statues’ from public veneration, balancing its condemnation of excessively modern art with an equal rejection of kitsch.13 The arguments against kitsch were widely repeated. In the Clergy Review, a British magazine aimed at parish priests and edited by O’Connell, Charles Blakeman, a Catholic artist, condemned the ‘inferior, standardized article’, urging priests to trust artists and to allow them freedom.14 A decade later, when the Second Vatican Council’s ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ of 1963 explicitly endorsed modern art for churches, J. D. Crichton, an English parish priest and liturgical writer, emphasised the sacredness of individual work in the creation of art for the Church:

A picture that is no more than a painted photograph, a statue that is poured out of a mould, made of inferior material by people who have no care for its quality or for its purpose, is incapable of arousing a response from the user, unless it be one of disgust. The Constitution … uses the expression humanis operibus which we may translate as ‘the works of man’s hands’ and we may add that it is because they are the works of man’s hands that they can give glory to God and reflect his beauty. Anything less cannot.15

Popular devotional art was criticised as being sentimental and overly feminine, a view Blakeman extended to other aspects of churches such as typical lace-adorned altars.16 Modern art, by contrast, needed to be virile, and so the ‘hieratic’ figure was advocated: recognisably human, yet sufficiently abstracted and reinterpreted as to possess symbolic qualities, severe enough to inspire devotion without arousing undue emotion.17 Emotional restraint was seen as a quality of liturgical prayer in contrast to popular devotions and was therefore advocated for liturgical art by Romano Guardini in his widely published book, The Spirit of the Liturgy.18 The ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ continued this theme by emphasising the liturgical role of church art, as ‘signs and symbols of heavenly realities’.19 Throughout this period, therefore, the Church demanded a good quality of original art and permitted some aspects of modern styles depending on context, a desire that coincided with the interests of many modern architects who wanted to work with artists.

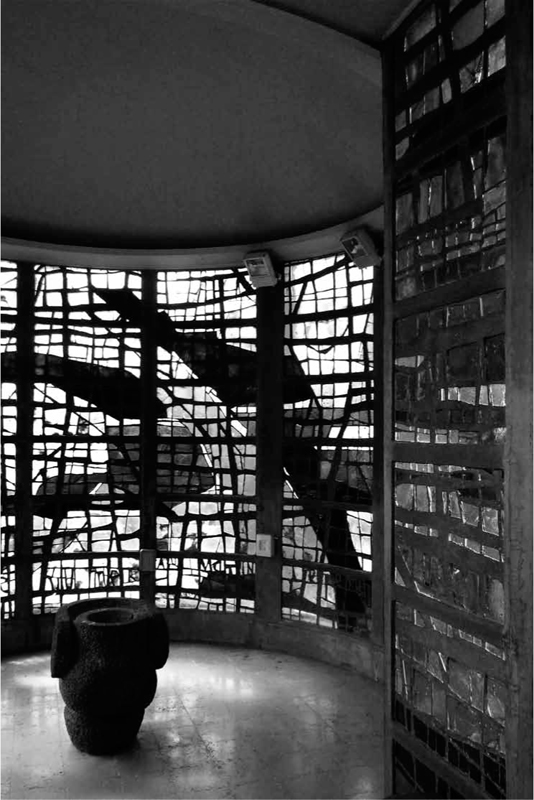

Undeterred by controversy and spurred by sympathetic patrons, Couturier and his colleagues in the Art Sacré movement in France were a major force in popularising modern sacred art and making it acceptable within the Church. Audincourt employed a more unified scheme than Assy: Fernand Léger designed a series of clerestory windows with recognisable but non-figurative emblems of the Passion, while Jean Bazaine created entirely abstract dalle de verre windows for the cylindrical baptistery, dark nervous lines crossing swathes of orange and grey (Figure 5.1). The use of dalle de verre as an element of the church’s modern architecture was an important aspect of this widely published building: in Anton Henze and Theodor Filthaut’s book, Contemporary Church Art, published by Catholic publishers Sheed & Ward, Audincourt’s glazing was said to be unified with the substance of the architecture, ‘technically part of the wall’, a statement of great significance for any modern architects who doubted the desirability of ornament.20 The French model of sacred artistic commissions would become highly influential in Britain in the 1950s.

5.1 Église du Sacré-Coeur, Audincourt, by Maurice Novarina, 1951. View of baptistery with glass by Jean Bazaine. © ADAGP, Paris, and DACS, London, 2013. Photo: Denis Mathieu, 2013

MODERN CHURCH ART IN BRITAIN: COVENTRY CATHEDRAL

Uniting the New Empiricism of post-war British architecture with the concept of the basilica of sacred art inspired by these French models was Coventry Cathedral. Basil Spence won the competition for this Anglican cathedral in 1951 with a design that aroused much controversy in the press for its modernism, despite his insistence on its historical basis, its conservative basilican plan and his intention to build it substantially in stone. Behind the altar Spence planned a magnificent tapestry by Graham Sutherland, while modern stained glass would line the nave and form a dramatic backdrop to the baptistery. Spence visited Sutherland in France to invite him to take on the commission, and the two visited the chapel at Vence decorated by Matisse. Significantly, the subject of Sutherland’s tapestry, Christ in Glory, was interpreted through the book of Revelation, also the source for Lurçat’s apocalyptic tapestry at Assy. Spence had thought of Sutherland because he had seen a crucifixion painting the artist had made for the Anglican church of St Matthew in Northampton, a striking commission from a patron who also emulated the Art Sacré movement, its vicar Walter Hussey.21

For Coventry’s baptistery window, Spence approached John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens around 1955. Part of the attraction of Piper for Spence was that he was a well-established modern painter, and his move into working with stained glass, sympathetically executed by Reyntiens, resembled the trajectory of Fernand Léger when the latter designed the windows for Audincourt.22 Piper and Reyntiens were also keen to emulate modern French stained glass.23 At Coventry, their baptistery window consisted of small panels of leaded glass in an abstract design of a blaze of coloured light: a similar approach to Bazaine’s at Audincourt, though more traditional in technique. Spence modelled Coventry closely on the pioneering French churches, and the cathedral aroused widespread public interest in Britain in modern church architecture and sacred art. Though Coventry was not always well received by architectural critics, it had a great impact on the architectural profession in Britain that was sustained throughout the lengthy process of its building, which only began in 1955 and was not complete until 1962.24 Spence’s concept of a basilica of modern art was adopted and imitated by many Roman Catholic architects and clergy.

5.2 St Aidan, East Acton, London, by Burles & Newton, 1959–61. View of nave: frieze of the Stations of the Cross by Arthur Fleischmann; painting of the Crucifixion by Graham Sutherland, c.1964. Courtesy of the Estate of Graham Sutherland. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

FROM COVENTRY TO CATHOLICISM

Coventry’s connections to subsequent Roman Catholic church art were often literal, as two case studies will show. In Lancaster, the church of St Bernadette, designed by Tom Mellor, was opened in 1958, a New Empiricist building of brick, stone and steel. Shortly after the church was opened, the timber panels of its reredos were daringly painted with an outline figure of Christ in Majesty, flanked by angels and overlaid with bold patches of primary colours, commissioned from John Piper. The church also included artworks by well-known Catholic sculptors Peter Watts and Michael Clark. At St Aidan at East Acton in London, meanwhile, a basilican reinforced-concrete church designed by Burles & Newton was opened in 1961 and subsequently filled with works of art, most of which were planned from the beginning. Behind its high altar was a bright red canvas of the Crucifixion by Graham Sutherland with an emaciated, tortured figure of Christ, while more conventional works adorned the church throughout (Figure 5.2, Plate 5).

Sutherland’s Crucifixion at East Acton was similar to his canvas at Northampton: red, instead of blue, but the same gaunt figure; and it was in fact his third, since another similar scene was woven into the base of the Coventry tapestry. St Aidan’s Crucifixion was the most overtly modern of the three: over the cross was an electric light and at its base a chain-link fence, references to the prison camp that had been only implicit in his previous images, a frequent theme of post-war Crucifixions, including that of Germaine Richier at Assy. Significantly, Sutherland was a Roman Catholic convert, and his work for St Aidan was his first for a Catholic church, answering a complaint that architectural critic Joseph Rykwert had made in France that Sutherland had so far been overlooked by Catholics.25

Sutherland’s appointment at East Acton was eagerly endorsed by the parish priest, James Ethrington, who evidently wished to assume the role of enlightened patron of modern art in emulation of Hussey at Northampton and, later, Chichester Cathedral. Around 1964, when his church’s artistic commissions were complete, Ethrington published a booklet on St Aidan’s artworks, inviting an art critic for a national newspaper, Terence Mullaly, to contribute an endorsement. Ethrington noted that the booklet was intended to reach beyond Catholics, ‘to draw attention to features of St. Aidan’s Church likely to be of interest to the general public’.26 Its purpose, and therefore also one purpose of the artworks, was to bring this church to a certain level of elite appreciation and to raise awareness of a Catholic artistic culture. Sutherland was here claimed for Catholicism, lending his credentials to the other more conventional artists whose work was placed alongside his: Kossowski, already well known and requested by churches across Britain; Arthur Fleischmann, a Hungarian artist who had made work for the Vatican at its 1958 Brussels Exposition pavilion; Roy de Maistre, an Australian painter who had earlier completed a series of Stations of the Cross at Westminster Cathedral; Philip Lindsey Clark, an eminent sculptor; and several others.27 Mullaly emphasised the importance of this original sacred art in transforming the reputation for kitsch that adhered to Christian and especially Roman Catholic churches: ‘during rather more than the last 150 years religious art has plumbed the depths of sentimentality and triviality’, he wrote; ‘St Aidan’s has broken with this bad old tradition’.28

This was exactly what the Vatican’s ‘Instruction on Sacred Art’ demanded. Had Sutherland’s Crucifixion painting at East Acton been made in the 1950s, it might have tested the limits of acceptability, but by the time of its unveiling in 1963 modern religious art was tolerated by Church and public alike, and the painting was well received. Catholic weekly The Tablet explained its purpose in relation to the new modern architecture and atmosphere of Catholic churches: ‘Clean lines, unpainted wood, and beauty unadorned are the order of the day. Gone are the wedding-cake altars, the sugar-plum statues and sad-eyed madonnas, and many heaved a gusty sight of relief at their departure’.29 Another writer, however, questioned Sutherland’s emphasis on suffering at the expense of other interpretations of the Crucifixion and, interviewing teenage parishioners, thought its devotional purpose not wholly satisfied.30 Yet the fact that such a work could be commissioned without substantial controversy was no doubt largely thanks to Coventry Cathedral. Coventry made modern sacred art acceptable and desirable, motivating Catholics to participate in modern high culture and to welcome it into their churches.

The collaboration of Piper and Reyntiens at Coventry was equally significant to Roman Catholic church architecture. At St Bernadette, Lancaster, the choice of Piper was exceptional, since he was not Catholic (Plate 6, Figure 5.3). The impact of his work in suburban Lancaster must have been potent, though, significantly, it was a young parish. A reporter for the Daily Express, attempting to whip up a scandal, found only praise for Piper: ‘We should feel honoured that an artist of Piper’s quality has been able to paint it for us’, said a ‘church committee man’; the parish priest who commissioned it, Christopher Aspinall, was said to have ‘loved the painting’; and a 29-year-old ‘churchgoer’ added: ‘Some people around here are too old-fashioned. They seem to think no one could pray properly with such a “loud” painting above the altar. But times are changing.’31 Like Sutherland at East Acton, Piper’s mainstream renown lent cultural credibility to the Church. His painting, dominating Mellor’s building though integrated with it, was an act of faith by the parish in the capacity of the artist to speak to modern people about Christian themes in a new way that also inspired devotion.

5.3 St Bernadette, Lancaster, by Tom Mellor, 1958. Reredos painting by John Piper. Courtesy of the Estate of John Piper. Photographer unknown, c.1958. Source: parish archive

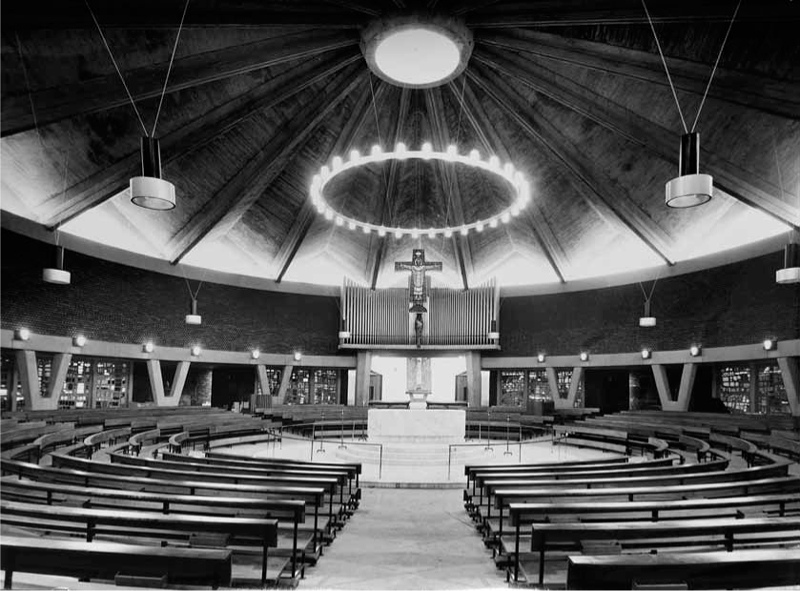

Reyntiens, meanwhile, was a Catholic, a graduate of Edinburgh College of Art who had trained in the stained-glass workshop of Joseph Nuttgens. Following the Coventry commission, Piper and Reyntiens were invited by Frederick Gibberd to provide stained glass in dalle de verre for the Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool. Gibberd had investigated another prolific stained-glass designer of this period, Charles Norris, a Benedictine monk at Buckfast Abbey in Devon. Norris had made an enormous scheme of dalle de verre windows for Our Lady of Fatima in Harlow New Town – a church Gibberd knew well, since he was the architect planner for Harlow. Eventually Gibberd admitted he disliked Norris’s work and recommended Geoffrey Clarke, one of the designers of Coventry’s nave windows.32 Gibberd sent Heenan to visit Coventry, and the decision to commission Piper and Reyntiens followed.33 A Dominican, Illtud Evans, advised Heenan that Reyntiens was ‘an excellent Catholic, with an informed knowledge of his faith which is of such importance in the iconography and design of glass for a sacred building’ and ‘the best stained glass artist working in England today’.34 Reyntiens had already been at work in the Archdiocese of Liverpool for the church of St Mary, Leyland by Weightman & Bullen, where early discussions about commissioning artists also began with reference to Coventry.35 The national prestige that Piper and Reyntiens’s partnership had attained through Coventry Cathedral was a significant factor in the decision to employ them, and Reyntiens’s Catholicism reassured the clergy. Gibberd was impressed by the broad architectonic scale of their work at Coventry, in contrast to Norris’s crowded figurative windows at Harlow, a taste that Piper and Reyntiens amply satisfied with their trinity of sunbursts in the Liverpool lantern (Plate 7).

In one point, however, Basil Spence had himself been influenced by a British Catholic precedent for modern religious art. Coventry’s external bronze sculpture by Jacob Epstein of the cathedral’s patron St Michael defeating the devil seemed to hover weightlessly against the sandstone wall, a form that suited Spence’s modernist intentions since it did not appear to be an ornament but an autonomous object. Spence had already seen a similar work at the Catholic convent of the Holy Child Jesus at Cavendish Square in London (Figure 5.4).36 Here Epstein had been commissioned in 1951 to create an external sculpture of the Madonna and Child, a work made of lead salvaged from the rooftops during their repair and suspended on the wall of a bridge linking two convent buildings. The commission came from the architect of the rebuilding of the bomb-damaged convent, Louis Osman, who claimed to have invented the idea of the levitating sculpture. Osman invited Epstein, a Jew, to work on the project without telling the convent’s nuns, who were eventually persuaded to accept the piece through encouragement from art historian Kenneth Clark, alongside a substantial donation from the Arts Council and Epstein’s willingness to be instructed on the subject of the Virgin Mary.37

Epstein had long been interested in Christian iconography, and though many of his pre-war religious figures had been condemned as blasphemous, they had all been speculatively made for sale rather than commissioned. Though they were titled with Christian themes, their intention was to evoke universal principles. His image for Cavendish Square was more theologically specific: the Virgin presented the Christ child to the secular world (literally, since it overlooked Oxford Street, the commercial heart of London); the child’s outstretched arms recalled the Crucifixion, and his horizontal draperies reprised the shroud in Epstein’s earlier figure of the Resurrection. When this sculpture was inaugurated in 1953 by Rab Butler, Chancellor of the Exchequer, it had an electrifying effect: architecture critic Robert Furneaux Jordan thought it the most important public artwork in London for centuries, and Epstein found himself suddenly a celebrity, in demand for monumental and religious sculpture.38 It caused a debate in the Catholic press equivalent to that over Our Lady of Victories: Catholic sculptor Peter Watts, who made the Stations of the Cross at St Bernadette, Lancaster, thought it essentially un-Christian and non-devotional, while Lance Wright countered that the modern artist’s personal interpretation of a religious theme made Christianity accessible to the world in a comprehensible language.39 It was not a work of church art, but it catalysed the acceptance of modern art by the Catholic Church in Britain.

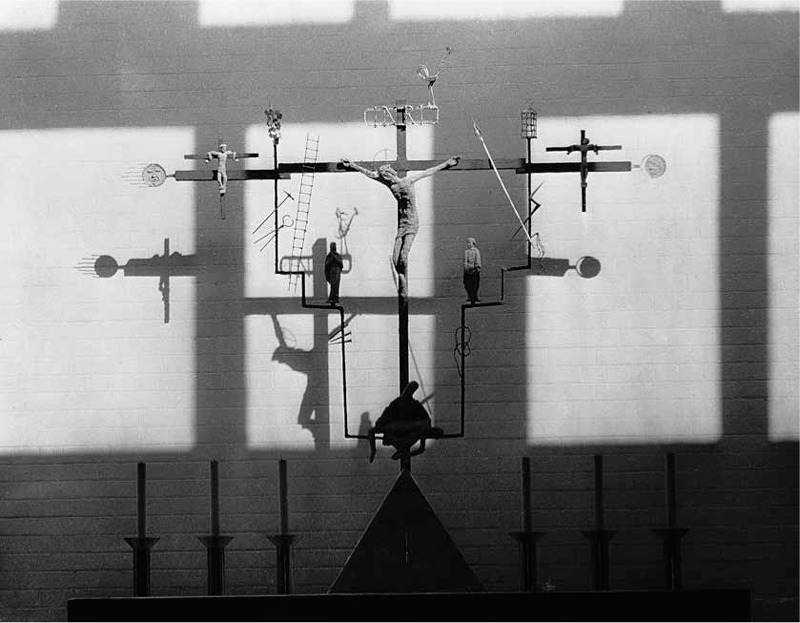

Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s church of St Charles Borromeo in Glasgow drew on this appreciation of Epstein. Sculptor Benno Schotz, a Jewish immigrant often compared to Epstein, was commissioned for major work, his modern figurative sculpture crowding Coia’s Coventry-like church: near-life-size terracotta figures depicted the Stations of the Cross; a bronze angel clapping cymbals held the sanctuary lamp; and a crucifix with bronze figures of Christ, the Virgin Mary and St John stood behind the marble altar surrounded by a halo of golden shards (Figure 5.5). Coia invited Schotz, a colleague at the Glasgow School of Art, to carry out the commissions, which were completed by around 1961. If Coventry was a reference point, however, Coia’s intentions were different: Schotz’s sculpture was to be integrated with the wall rather than detached from it, giving a ‘horizontal wavy movement’, so Schotz used the reinforced concrete beams as a base and chose terracotta to match the brickwork.40 In contrast to Coventry’s mainly symbolic and abstract internal artworks, this commission filled the church with figures intended for devotional use. Schotz’s work was accordingly less challenging to Catholic taste than Epstein’s more radical reinterpretations, yet the fact that these artworks were commissioned from a well-established non-Catholic modern artist was a substantial advance in the spirit of the Art Sacré movement. Schotz worked concurrently for Gillespie, Kidd & Coia’s church of St Paul, Glenrothes, whose parish priest, Pierce Grace, had seen and appreciated Schotz’s work for St Charles. MacMillan, approving his appointment, gave the sculptor a sketch for the crucifix based on photographs of Catalan crosses that he had seen in L’Art sacré. To the arms of the cross Schotz attached symbols of the Passion, like those in Léger’s windows at Audincourt (Figure 5.6). Grace, though he was impressed by the restrained devotional feeling of Schotz’s crucifix, felt unable to inform Archbishop Gray of its authorship in advance, but the sculpture was widely admired on the opening of the church in 1958, and, when he discovered that Schotz was its artist, Gray declared that he thought it was ‘fit for the Vatican’.41

5.4 Madonna and Child by Jacob Epstein at Convent of the Holy Child Jesus, Cavendish Square, London, 1951–53. Photo: Steve Cadman, 2011

5.5 St Charles Borromeo, Kelvinside, Glasgow, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1956–60. Stations of the Cross by Benno Schotz, RSA. Courtesy of the Trustees of the late Benno Schotz, RSA. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

5.6 St Paul, Glenrothes, by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, 1956–58. Crucifixion by Benno Schotz, RSA. Courtesy of the Trustees of the late Benno Schotz, RSA. Photographer unknown, c.1958. Source: Glasgow School of Art

PATRONAGE AND DEBATE: LIVERPOOL AND LEYLAND

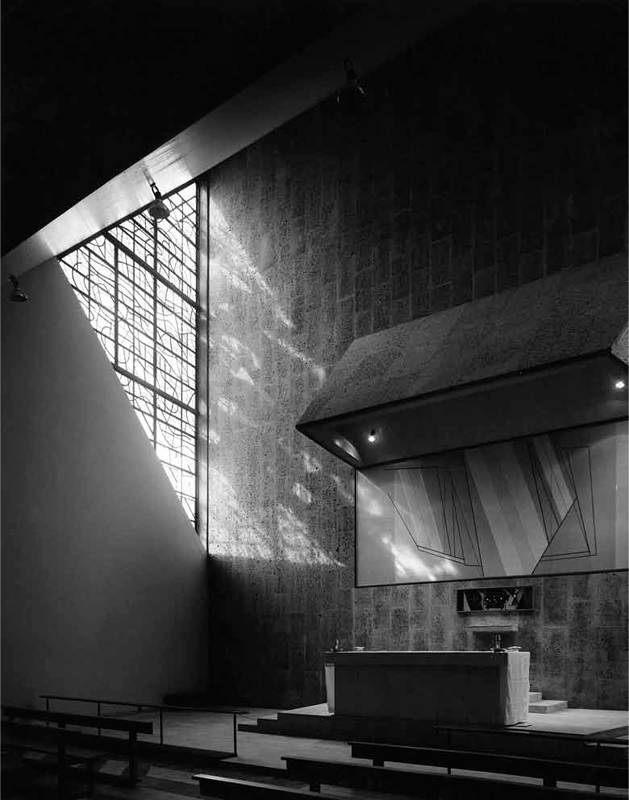

On at least one occasion the Church’s desire for figurative art conflicted with an architect’s preferences. At Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, Robert Brumby was commissioned to make a sculpture of the Virgin and Child for the lady chapel (Figure 5.7). This commission was made by the clergy without consulting Gibberd, who angrily complained when he discovered it. Augustine Harris, auxiliary bishop of Liverpool, defended their action, arguing that Gibberd’s emphasis on abstract art was inappropriate for a figure of popular devotion.42 The clergy on the cathedral committee had already been concerned about Gibberd’s appointment of established abstract painter Ceri Richards for a canvas and designs for the tabernacle and stained glass in the Blessed Sacrament chapel. His yellow and white painting and blue and yellow glass design for Liverpool were entirely abstract, some more overt symbolism entering the tabernacle panels (Figure 5.8). Richards’s work received a mixed reception from the cathedral committee, some of whom could not conceal their disliked of it from Gibberd.43 The choice of artist had been tentatively accepted by Beck, however, who took over from Heenan in 1964, and Beck had personally approved the designs at various stages. Beck had debated the desirability of abstraction with Gibberd, accepting abstract art in certain contexts, but advocating a more conventional treatment for devotional images. Reassured by advice from Reyntiens supporting Richards’s appointment and having inspected some of the artist’s earlier work, Beck approved the commission because it required ‘something which will give a visitor to the Chapel, particularly the ordinary visitor who comes to pray there, a sense of peace, tranquillity and majesty, with some awareness, I hope, of the presence of God’.44 In other words it was specifically the theocentric nature of the Blessed Sacrament chapel that made abstraction possible, and seemingly also a desire to engage non-Catholic visitors.

5.7 Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool, by Frederick Gibberd, 1960–67. Lady chapel: sculpture of Madonna and Child by Robert Brumby; stained glass by Margaret Traherne. By permission of Robert Brumby and the Dean of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2012

5.8 Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool, by Frederick Gibberd, 1960–67. Blessed Sacrament chapel: painting, tabernacle and stained-glass design by Ceri Richards © Estate of Ceri Richards, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013; stained glass executed by Patrick Reyntiens, © Patrick Reyntiens, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013. By permission of the Dean of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King. Photo: Henk Snoek. Source: Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Library Photographs Collection

In contrast, Beck refused Gibberd’s request to appoint Leslie Thornton for the crucifix after viewing samples of this modernist sculptor’s earlier renditions of the subject. Beck wrote to Gibberd:

I do not think it is possible to regard the crucifixes and statues which are placed in our churches simply and solely as works of art, in the sense in which a work of art can be presented in secular surroundings. The purpose of these objects is also to foster devotion, and I would maintain that they are more truly works of art in the measure in which they achieve this purpose. I do not believe that this necessarily restricts the artist to a realistic and representational design, but I think it does exclude the abstract and impressionist presentation.45

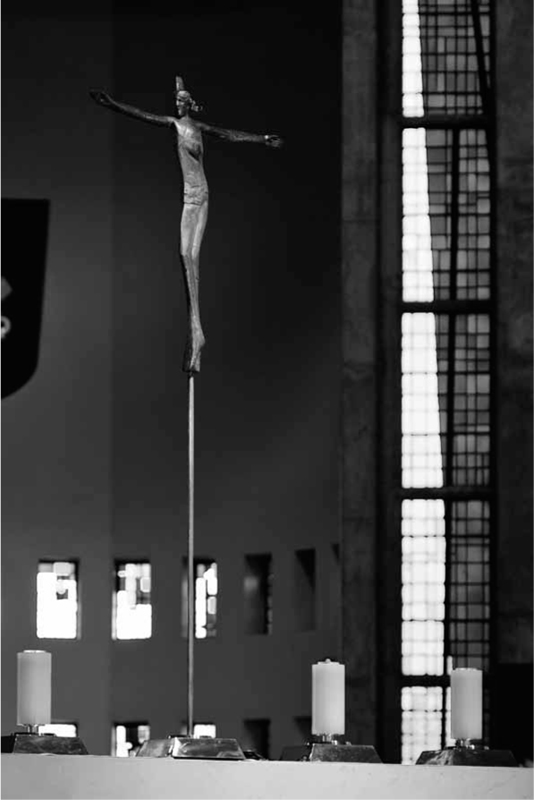

After several prominent artists refused the commission for a crucifix suspended from the baldachino, Elisabeth Frink was asked for a smaller work to place behind the altar, with Gibberd’s approval (Figure 5.9).46 Frink made a thin, barely distinguishable figure whose arms alone formed the cross beam, but despite its novelty the clergy were favourable: ‘We are not sure about the liturgical correctness of the absence of the cross-beam’, wrote Beck, ‘but I, personally, and others of the committee think the symbolism of this is very striking since it portrays a gesture of love for all men, and not merely the suffering of a victim’.47 Frink’s work balanced the requirement for a recognisable crucifixion figure with a novel form and complexity of meaning.

At St Mary’s church in Leyland, a similar and earlier unified programme of modern artworks completed this church in the Archdiocese of Liverpool. The church was run by Benedictines from Ampleforth, who appointed one of their number, Edmund Fitzsimons, as the parish priest. Fitzsimons undertook unusually extensive preparatory studies. Not only did he read about modern church architecture, subscribing to Churchbuilding, but in 1959 he went on a tour organised by the Birmingham University Institute for the Study of Worship and Religious Architecture titled ‘Modern Glass in France and Switzerland’, including visits to Le Raincy, Audincourt and Ronchamp.48 Fitzsimons also took advice on church art from Crichton, who warned him against resorting to ecclesiastical suppliers.49

Crichton attended a meeting in 1961 between Fitzsimons and architect Jerzy Faczynski of Weightman & Bullen, where commissions and schemes for the church’s artworks were decided. Geoffrey Clarke, Charles Norris and Reyntiens were proposed for the stained glass, the latter eventually appointed. The Stations of the Cross were to be ‘based on [a] linear conception such as “wired sculpture” or on “statuette types”’, Faczynski proposing Henry Moore as the sculptor. David John was to be asked for a statue of the Virgin Mary, and, for the external tympanum, Crichton suggested Kossowski.50 Most of this ambitious scheme went to plan (Plate 8, Figure 5.10): Reyntiens made an abstract composition in dalle de verre whose blue and green colours symbolised the Creation and the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary; Kossowski produced one of his most dramatic works, an external ceramic frieze of the Last Judgement and also made a ceramic cross depicting Christ as High Priest to hang over the altar. Faczynski himself designed a tapestry to hang behind the Blessed Sacrament chapel altar, visible from the nave of the church, directly inspired by Sutherland at Coventry, but here with an image of the Crucifixion more orthodox than those of Sutherland. The diocese made little objection to the scheme of artworks. Its one complaint was that Kossowski’s cross was not adequately liturgical and an additional crucifix had to be added for the altar.51

5.9 Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool, by Frederick Gibberd, 1960–67. Crucifix by Elisabeth Frink © Estate of Elisabeth Frink, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013; stained glass behind by John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens, © Patrick Reyntiens, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013. By permission of the Dean of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

5.10 St Mary, Leyland, by Weightman & Bullen, 1960–64. Suspended crucifix in ceramic by Adam Kossowski; Virgin and Child by Ian Stuart; Blessed Sacrament chapel tapestry of the Crucifixion by Jerzy Faczynski, made by the Edinburgh Tapestry Company; stained glass by Patrick Reyntiens, © Patrick Reyntiens, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013. Photo: Elsam, Mann & Cooper, c.1964. Source: parish archive

A Liverpool sculptor, Arthur Dooley, accepted the commission for the Stations of the Cross, producing a striking series in bronze placed in the V-shaped pillars surrounding the nave. Dooley was by then a local celebrity, a Catholic convert and a communist. He used his sculptures at Leyland as an opportunity to explore modern political themes allied to the narrative subjects. ‘St. Veronica of the Stations’, he wrote, ‘embodies the idea of the natural goodness and humanity in the very nature of women (and men)’; and he explained how the figure of Simon of Cyrene not only helped Christ carry the cross but was also the soldier nailing Christ to it: ‘I hope to show by this that in a society where the ruling classes have the power to govern and dictate to the workers, then the ordinary man loses his right to make personal decisions’.52 Christ’s death was announced by a newspaper seller’s billboard; the Roman soldiers were faceless and machine-like, some with swastikas, others with Franco-era Spanish coins embedded in them; the imprint of Christ’s face on Veronica’s veil became graffiti on a brick wall (Figure 5.11); an emaciated child symbolised global poverty.53 This radical commission brought Leyland widespread publicity after it was installed in 1965, a television documentary bringing it to a national audience while the Catholic press delighted in the sensational story.54 Fitzsimons evidently wanted to position Leyland at the summit of Roman Catholic avant-garde art at a time when Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral was still under construction, demonstrating the Church’s modernity and culture to the nation.

5.11 St Mary, Leyland, by Weightman & Bullen, 1960–64. Stations of the Cross by Arthur Dooley (Veronica’s veil); stained glass behind by Patrick Reyntiens © Patrick Reyntiens, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

CATHOLIC ARTISTIC CULTURE

While the use of such notable artists as Schotz, Sutherland, Piper and Dooley made headlines and attracted non-Catholic interest, most church art remained relatively conventional. At St Aidan, Sutherland’s Crucifixion painting contrasted with the more familiar forms of works by Philip Lindsey Clark and Adam Kossowski, and at St Bernadette, Lancaster, the Stations of the Cross were representational, carved in stone by Peter Watts, while other sculptures there were made by Clark’s son, Michael. These artists contributed a wealth of sculpture to new churches across Britain. The inspiration for their approach was Eric Gill. Gill’s most important church work had been the series of Stations of the Cross he produced for Westminster Cathedral from 1915, which, though controversial at the time for their unfamiliar hieratic style, were soon accepted and long remained influential.55 Watts’s Stations of the Cross at Lancaster, for example, used a tough formal style of figure, conveying emotions associated with their subject matter through angular and calculatedly uncomfortable compositions (Figure 5.12). In a similar mode, artist David John produced a great many pieces for churches of all kinds. For F. X. Velarde, he created integrated architectural sculpture at the shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes in Blackpool and sculptural reliefs for the entrance front of St Luke, Pinner. In wood, he carved modern figurative statues, many in churches by Weightman & Bullen, including that at Leyland. One of his most interesting and expressive works was a long frieze of the Stations of the Cross in wood for the church of St Mary Magdalene, Cudworth, in 1961, one of several of his works there for architect John Rochford (Figure 5.13). These artists and others sustained and developed a distinctive culture – even a ‘tradition’ – of twentieth-century Roman Catholic church art owing more to Gill’s version of the Arts and Crafts movement than to avant-garde modernism.

One important means of cultivating the sense of a unified Catholic artistic culture was the Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen, founded in 1929, its name suggestive of a medieval corporation as interpreted by William Morris and Gill, though it was renamed the Society of Catholic Artists in 1964.56 Architects were just as prominent within it as artists. The older generation included Philip Lindsey Clark and Goodhart-Rendel; Alfred Bullen of Weightman & Bullen was its secretary in the 1950s.57 Younger members later took over, including Paul Quail, a stained-glass artist, Lance Wright, Gerard Goalen, David John and Adam Kossowski. Through the organisation of exhibitions and meetings it brought together all generations and disciplines of artists and designers, often with a special focus on liturgical art. In 1960, for example, the guild staged an exhibition, ‘Church Building and Art’, at the Building Centre in London, including Stations of the Cross made for the church of the Holy Apostles, Pimlico, by Philip Lindsey Clark; Graham Sutherland’s Crucifixion painting at Chichester; competition designs for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral by Frederick Gibberd, Denys Lasdun and Lance Wright; and works by Robert Maguire, Francis Pollen, Patrick Reyntiens and others.58 It is tempting to see this exhibition as another catalyst for the acceptance of modern art in Catholic churches in the 1960s.

Perhaps this group’s most important activity for developing an intellectual approach to art as well as for attracting patronage was its annual ‘Visual Arts Week’ at Spode House in Staffordshire. Spode House was a wing of a Dominican priory, and this event took place with the encouragement and organisation of Conrad Pepler, a Dominican priest who had been raised by his father Hilary in Gill’s artistic community at Ditchling. The ‘Visual Arts Weeks’ were well attended by artists, architects, clergy and Catholic intellectuals and involved a brief but often transformative ferment of creative energy. In 1956, for example, delegates engaged in team design projects for a convent chapel and a parish church: an architect led each team, and members designed artworks and liturgical furnishings together.59 The title of the 1962 event was ‘Sacred Art in a Geometric Environment’, and its programme included a demonstration of sculpture by David John and lectures from Joseph Rykwert, architectural critic Colin Rowe and Christopher Cornford, newly appointed at the Royal College of Art.60 Speakers were sometimes invited from France, including theologian Louis Bouyer, who wrote on liturgy and architecture, and Maurice Cocagnac, a Dominican, editor of L’Art sacré and an architect and painter.61 These conferences were evidently vital events both in the development of a Catholic culture of the arts and in its engagement with wider modern culture.

There was an extremely broad range of art and of architects’ collaborations with artists in post-war British Roman Catholic church architecture, from the conventional statuary that many still liked to the thoughtful and comprehensive integration of contemporary art and architecture at Leyland and Liverpool. Modern artists and architects aimed to explore the limits of acceptability in church art by presenting familiar devotional elements in unexpected new forms, forcing the faithful to think more deeply about how their devotions might be interpreted in ways that were relevant in the modern world. At the same time, modern art was commissioned for a wider public audience, intended to demonstrate Catholic participation in modern culture to the world beyond the Church.

5.12 St Bernadette, Lancaster, by Tom Mellor, 1958. Stations of the Cross by Peter Watts (Nailing of Christ to the Cross). By permission of Richard Watts. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2011

5.13 St Mary Magdalene, Cudworth, by John Rochford, 1960–61. Stations of the Cross by David John. By permission of David John. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

NOTES

1 The idea comes from Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, 187–97.

2 Mumford, The CIAM Discourse, 203–13; Jacqueline Tyrwhitt, Josep Luis Sert and Ernesto Rogers (eds), The Heart of the City: Towards the Humanisation of Urban Life (London: Lund Humphries, 1952).

3 Seemingly this is a subject which has not yet been well researched (see for example Robert Melville, ‘Personnages [sic] in Iron’, Architectural Review [Sept. 1950], 147–51).

4 Dolores Mitchell, ‘Art Patronage by the London County Council (L.C.C.), 1948–1965’, Leonardo 10 (1977), 207–12.

5 Nigel J. Abercrombie, ‘The Approach to English Local Authorities, 1963–1978’, in John Pick (ed.), The State and the Arts (Eastbourne: John Offord, 1980), 66–7; John Pick, ‘Introduction: The Best for the Most’, ibid. 9–14.

6 Rubin, Modern Sacred Art and the Church of Assy, 35–7.

7 Ibid. 37–8; Joseph Pichard, L’Art sacré moderne (Paris: B. Arthaud, 1953), 97, 113–14; Régamey was less open to non-Christian artists, but did not exclude them (P.-R. Régamey, Art sacré au XXe siècle? [Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1952], 75–7).

8 Orenduff, Transformation of Catholic Religious Art, 62.

9 Rubin, Modern Sacred Art and the Church of Assy, 70–71.

10 For a substantial and detailed discussion of abstract art in post-war Catholic thought and practice, see George Mercier, L’Art abstrait dans l’art sacré: La Tendance non-figurative dans l’art sacré chrétien contemporain (Paris: Éditions E. De Boccard, 1964).

11 Adrian Fortescue, The Ceremonies of the Roman Rite Described, revd J. B. O’Connell (London: Burns Oates & Washbourne, 1948), 7; J. B. O’Connell, ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 43 (1958), 41; but see id., ‘Questions and Answers’, Clergy Review 46 (1961), 49–50; Orenduff, Transformation of Catholic Religious Art, 135–55.

12 For Stüflesser statuary (though some may have been by Tyrolean competitor firms), see for example St Joseph, Ramsbottom, CBRN (1963), 90–91; Brian Moorhouse, St Augustine’s, Lowerhouse: Centenary, 1896–1996 (1996), 28 (SDA, Parish Files); St Thomas More, Sheldon, in Bryan Little, ‘Four New Birmingham Churches’, Clergy Review 55 (1970), 1009–14 (1014). In many more cases a reference to statuary ‘carved in Italy’ seems to be Stüflesser.

13 Colleen McDannell, Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 171, ch. 6.

14 Charles Blakeman, ‘The Problem of Church Art’, Clergy Review 40 (1955), 22–33.

15 J. D. Crichton, ‘Art at the Service of the Liturgy’, in id. (ed.), The Liturgy and the Future (Tenbury Wells: Fowler Wright Books, 1966), 164–73 (164–5).

16 Blakeman, ‘The Problem of Church Art’, 27; McDannell, Material Christianity, 180–85; for another view, see Susan O’Brien, ‘Making Catholic Spaces: Women, Décor, and Devotion in the English Catholic Church, 1840–1900’, in Diana Wood (ed.), The Church and the Arts: Papers Read at the 1990 Summer Meeting and the 1991 Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society, Studies in Church History 28 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992). Walker notes that anti-kitsch rhetoric had a longer history (‘Developments in Catholic Churchbuilding’, 138–9).

17 McDannell, Material Christianity, 177–8; see also for example Roulin, Modern Church Architecture, 805.

18 Romano Guardini, The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. Ada Lane (London: Sheed & Ward, 1930), 12–19 (esp. n. on p. 12).

19 ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’, in Abbott, The Documents of Vatican II, 174.

20 Anton Henze, ‘The Potentialities of Modern Church Art and Its Position in History’, in Anton Henze and Theodor Filthaut (eds), Contemporary Church Art, trans. Cecily Hastings (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1956), 15–48 (31).

21 Basil Spence, Phoenix at Coventry: The Building of a Cathedral (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1962), 36–8; Garth Turner, ‘“Aesthete, Impresario, and Indomitable Persuader”: Walter Hussey at St Matthew’s, Northampton, and Chichester Cathedral’, in Wood (ed.), Church and the Arts, 524–5.

22 Spence, Phoenix at Coventry, 52–3.

23 June Osborne, John Piper and Stained Glass (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1997), 41–8, 27–33.

24 Spence, Phoenix at Coventry, 88, 105.

25 Joseph Rykwert, ‘Passé récent et problèmes actuels de l’art sacré’, in D. Mathew et al., Catholicisme Anglais (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1958), 291–8 (297–8).

26 James Ethrington, ‘The Church of St Aidan, East Acton, London, W3’, in James Ethrington and Terence Mullaly (eds), St Aidan’s, East Acton: The Church and its Art (London: n.p., c.1964), unpaginated.

27 ‘Biographical Notes’, in Ethrington and Mullaly (eds), St Aidan’s, East Acton.

28 Terence Mullaly, ‘Art at St Aidan’s’, in Ethrington and Mullaly (eds), St Aidan’s, East Acton. Mullaly later wrote an article on the church for The Telegraph, reprinted as ‘Challenge in the Church’, Bulletin of the Society of Catholic Artists (May 1968), 2–4 (ASCA).

29 ‘From Our Notebook’, The Tablet (23 Feb. 1963), 200.

30 Anthony P. Kirwin, ‘A Way Through the Weeds: Graham Sutherland’s “Crucifixion” in East Acton’, The Tablet (11 Jan. 1964), 181–2.

31 ‘Should This Painting be Rubbed Out?’, [Daily] Express (n.d.) [newspaper clipping] (LRCDA, parish file for St Bernadette).

32 Minutes of meeting of the Cathedral Executive Committee (12 Oct. 1961); Frederick Gibberd, ‘Report on Progress and Points for Discussion with his Grace the Archbishop and the Cathedral Committee’ (11 Jan. 1961) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/XI/A/2).

33 Frederick Gibberd, Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool (London: Architectural Press, 1968), 69.

34 Illtud Evans to Archbishop Heenan (9 Dec. 1961) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/IX/A/93).

35 ‘Notes on a Meeting with Dr. J. D. Crichton, Fr. B. E. Fitzsimons and J. Faczynski at Manchester, 10th August, 1961, concerning the art works for the new Church’ (parish archive, St Mary, Leyland, ‘New Church: Art Works’); Libby Horner, ‘Patrick Reyntiens’ Autonomous Panels: Myth, Music and Theatre’, Decorative Arts Society Journal 35 (2011), 63–80 (64–7).

36 Spence, Phoenix at Coventry, 68.

37 Jonathan Cronshaw, ‘“This Work Has Never Been Commissioned At All”: Jacob Epstein’s Madonna and Child’, Art and Christianity 66 (Summer 2011), 5–7; Evelyn Silber, The Sculpture of Epstein (Oxford: Phaidon, 1986), 55, 209; Jacob Epstein, Epstein: An Autobiography (London: Hulton Press, 1955), 235–6.

38 Spence, Phoenix at Coventry, 68; Epstein, Epstein, 236; Silber, The Sculpture of Epstein, 55.

39 For example Peter Watts, letter to the editor, The Tablet (31 Apr. 1952), 442; Iris Conlay, letter to the editor, The Tablet (7 June 1952), 465; Peter Watts, letter to the editor, The Tablet (14 June 1952), 482; W. E. Pattin, letter to the editor, The Tablet (14 June 1952), 482; Lance Wright, letter to the editor, The Tablet (21 June 1952), 502; Peter Watts, letter to the editor, The Tablet (21 June 1952), 502; Lance Wright, letter to the editor, The Tablet (28 June 1952), 524.

40 Benno Schotz to Jack Coia (24 Mar. 1961) (GSAA, GKC/CHK/1/7); Benno Schotz, Bronze in My Blood: The Memoirs of Benno Schotz (Edinburgh: Gordon Wright, 1981), 208–9.

41 Schotz, Bronze in My Blood, 210–12.

42 Augustine Harris to Gibberd (29 Oct. 1966) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/X/A/114).

43 Gibberd to Monsignor Thomas G. McKenna (Aug. 1966) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/X/A/108).

44 Beck to Gibberd (29 June 1965) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/X/A/75).

45 Beck to Gibberd (4 Mar. 1965) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/X/A/82).

46 Gibberd to Beck (20 Jan. 1967) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/X/A/123).

47 Beck to Gibberd (27 Feb. 1967) (LRCAA, Cathedral Collection, S2/X/A/125).

48 Frank Harrison, St Mary’s, Leyland: The History of a Catholic Community (Preston: n.p., 1995), 92–3; Edward Corbould, ‘St Mary’s Priory Church, Leyland’, Churchbuilding, 13 (Oct. 1964), 3–9 (3); see also George G. Pace, ‘Review of New Church: St Mary’s Priory, Leyland’, Clergy Review 50 (1965), 81–8. At the time of research, the parish archive of St Mary’s ‘New Church: Art Works’ box contained, amongst other things: a postcard and leaflet of Audincourt; a programme and papers from a conference on ‘New Church Architecture’ at Liverpool University of 1960, including papers by for example Robert Maguire and William Lockett on ‘New Church Buildings in France and Germany’, with Fitzsimons listed as a delegate; a leaflet on Gabriel Loire’s dalle de verre glass in France; and the itinerary for the Birmingham tour, dated 1959, including visits to Le Raincy, Audincourt and Ronchamp; an article on Pierre Fourmaintraux (Marian Curd, ‘Playing With Light’, Catholic Herald [12 May 1962]); an unreferenced newspaper cutting on modern churches in Mexico, including work by Felix Candela; copies of Churchbuilding; newsletters from the University of Birmingham Institute for the Study of Worship and Religious Architecture; correspondence with artists.

49 J. D. Crichton to Edmund Fitzsimons (9 July 1959) (parish archive, St Mary, Leyland, ‘New Church: Art Works’).

50 ‘Notes on a Meeting with Dr. J. D. Crichton, Fr. B. E. Fitzsimons and J. Faczynski at Manchester, 10th August, 1961, concerning the art works for the new Church’; Jonah Jones to Fitzsimons (26 Jan. 1962) (parish archive, St Mary, Leyland, ‘New Church: Art Works’).

51 Sites and Buildings Commission (19 July 1960) (LRCAA, Finance Collection, 12/S3/III).

52 Arthur Dooley, ‘Stations of the Cross’ (n.d.) (parish archive, St Mary, Leyland, ‘New Church, Art Works’).

53 Simon Caldwell, ‘One Man’s Passion’, The Universe English edn (26 Nov. 1995), 7.

54 A transcript of the BBC film, A Modern Passion (broadcast 7 Apr. 1966), is present in the ‘New Church, Art Works’ box of the parish archive of St Mary, Leyland.

55 Roulin, Modern Church Architecture, 34–5; Rykwert, ‘Passé recent et problèmes actuels’, 295–6.

56 Bulletin of the Society of Catholic Artists (Dec. 1964) (ASCA).

57 For example A. Bullen (Weightman & Bullen) to David John (5 Nov. 1956) (ASCA).

58 Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen, ‘Church Building & Art’ [exhibition notice] (Nov.–Dec. 1960) (ASCA); Iris Conlay, ‘Patronage the Only Answer’, Catholic Herald (9 Dec. 1960), 5.

59 Paul Quail, newsletter (June 1956) (ASCA). The following year the idea was extended to a design project for a ‘Catholic City Centre’: Conrad Pepler (Spode House) to Paul [Quail] (honorary secretary, Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen), 13 July [1956]; Paul Quail, typed news sheet (June 1957) (ASCA).

60 Programme for ‘Visual Arts Week’ (1962) (ASCA).

61 David John, telephone interview with Ambrose Gillick (12 June 2013); Louis Bouyer, Liturgy and Architecture (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1967).