9

Ritual and Community

Turner applies the notion of communitas, forged in pilgrimage ritual, to show how pilgrimages and their shrines can also lend themselves to the construction of national identities. Catholicism, he argues, often mobilises national sentiments to stimulate religious practice, while nationalism can receive a sacred status through its endorsement within religion.1 The revived pilgrimages of post-war Britain were overlaid with appeals to communal identities, both Roman Catholic and national. When the faithful engaged in religious rituals in environments overlaid with symbols of national and religious identity, they enacted that shared identity. If this identity-forming aspect of ritual and religious space was true of pilgrimages, it was also true of more everyday religious practices. Benedict Anderson and others argue that the social conformism of ritual lends itself to the imagining of communities: ritual creates a commonality of identity amongst its immediate actors and links them to all those others who share its actions.2 Rituals surrounding the building of a church and those involving civic space articulated communities of the parish and the city and brought them into being.3

Post-war Catholicism in Britain, however, was largely a religion of immigrants and often viewed as un-British. The imaginative geographies of pilgrimage might therefore be seen as attempts to claim a place for the Church within the nation, affirming the identity of a British (or at least a Scottish, English or Welsh) Roman Catholic community in opposition to its perceived foreignness. Meanwhile Irish and other immigrants sometimes sought to display their own national identities in church architecture, sometimes in tension with such British claims. National identities, however, were subsumed into the broader identity of Roman Catholicism, centred on Rome; and communities were also formed around the local centres of the parish and the city. Catholic identity in Britain was fragmented, focused on multiple centres and allegiances and in an uncertain relationship with the modern nation.

PILGRIMAGE AND THE NATION

While Marian pilgrimages such as those at Cardigan and Aylesford comprised locally situated variations on the international cult of the Virgin Mary, pilgrimages were also created around sites considered formative in the Catholic history of the nation. Two case studies illustrate this tendency: the shrine of St Ninian in Whithorn resulted from the revival of a medieval pilgrimage for Scotland, while a pilgrimage in central London manifested the modern cult of the Forty Martyrs of the Reformation in England and Wales. Both promoted the sense of a national Catholic identity through sacred rituals that retold history. One asserted the continuity of modern Catholicism with that of the past, nostalgically eliding the rupture of the Reformation, while the other brought that rupture to consciousness as a point of sacred memorial. Both forms had their place in reconciling Catholics to a nation that had historically rejected them.

At Whithorn on the south-west coast of Scotland a pilgrimage to St Ninian was revived in the early twentieth century under the bishop of Galloway, William Turner, with the encouragement of John Crichton-Stuart, the Marquess of Bute.4 St Ninian was a fifth-century Christian missionary to the Picts, bishop of a diocese dedicated to St Martin and the subject of a major medieval pilgrimage cult until its prohibition in 1581.5 The twentieth-century Catholic revival of this pilgrimage attempted to reinstate an element of the lost ritual landscape of medieval Scotland. Its focus was a cave behind a rocky beach four miles from the town, reputed to have been Ninian’s chapel, while a ruined Norman priory and cathedral on the town’s high street, where the saint was thought to be buried, were further landmarks. On St Ninian’s feast day in September, thousands of pilgrims would gather at the mouth of the cave to attend Mass at a temporary altar and to walk in procession through the town. The cave bore few traces of ancient use and was unlikely to have been a feature of the medieval pilgrimage. Its adoption in the twentieth century romantically evoked the hardships of the early Christian missionary. It was literally a liminal place, sited between land and sea, a space without conventional sacred or secular function, at the edge of the nation and, perhaps significantly, also close to the border with England.

The Catholic church of St Martin and St Ninian at Whithorn was used in these pilgrimage celebrations, but its Victorian iron building was too small for the cult’s growing popularity. The parish acquired a large plot of land on the high street around 1951, and, with the patronage of Crichton-Stuart’s grandson Lord David Stuart, launched a campaign for a pilgrimage church. Stuart commissioned Scottish architect Basil Spence for a design and urged the diocese to embark on a ‘National appeal for a National Shrine of St Ninian’.6 Spence’s design alluded to the mythic cave in a modern architecture tinged with historic and national references (Figure 9.1). The church was to be set back from the street and a stone figure of St Ninian placed before it. Pilgrims would pass through a screen, arriving at a cloistered courtyard paved with stones taken from the beach in front of the cave.7 The church’s long nave had cave-like granite walls curving inwards and daylight entered through slits angled towards the sanctuary.8 Spence’s design suggested the atmosphere of Ninian’s primitive church, and his building would have complemented the pilgrims’ experience of the seashore shrine. It also suggested a Scottish identity in its architecture with a monumental use of masonry and small castle-like windows.

9.1 Basil Spence, design for St Martin and St Ninian, Whithorn, 1951. Photograph of model. Source: © Courtesy of Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Spence, Glover and Ferguson Collection. Licensor, www.rcahms.gov.uk

A model was shown at one of the annual pilgrimages to great excitement, but after the bishop’s death in 1952 the project was shelved, as his successor Joseph McGee disliked Spence’s modernism.9 Nevertheless McGee asked all the parishes of the diocese of Galloway to contribute to a building fund, arguing it was ‘not simply … a matter of supplying the needs of the Catholic community of Whithorn but … one involving the prestige of the Catholic Church in this Diocese and, indeed, in Scotland’.10 Goodhart-Rendel was commissioned for a modest building seating only 200. His design followed Arts and Crafts principles with a local vernacular style, its plain neo-Gothic windows and harled exterior recalling churches of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Figure 9.2).11 In that period, Scottish Catholics could rarely worship in churches of this kind. Goodhart-Rendel’s design therefore implied a nostalgic reminder of underground Catholicism, while also resembling a typical Scottish parish church, perhaps helping to assert a general national allegiance for Catholicism in Scotland. The church’s simplicity avoided competing with the priory opposite, allowing the original medieval structure to retain its authenticity as the real shrine of St Ninian. The new church, opened in 1960, was too small for the crowds of pilgrims, who instead stood on a sloping strip of outdoor space behind it facing a permanent altar built at the church’s rear wall.

9.2 St Martin and St Ninian, Whithorn, by H. S. Goodhart-Rendel, 1955–60. Photo: Ambrose Gillick, 2012

In this attempt at reviving a medieval pilgrimage and creating a national shrine the parish and the diocese shaped a ritual that constructed a modern Scottish Catholic identity for its participants through an enactment of historical narrative. The procession between priory, church and cave revived the medieval pilgrimage so that pilgrims could identify themselves with their ancient forebears. In celebrating a saint who helped convert Scotland to Christianity, they confronted a point of origin of their faith in the history of the nation. Yet the pilgrimage was a re-telling rather than a re-enactment of history. The open-air gathering reinforced the absence of an adequate church; the makeshift altar on the beach made the absence of monuments felt; the medieval priory was in ruins. Though the Reformation was elided, it was everywhere present. The procession through the street, led by a priest in vestments and servers in cassocks, further defined the pilgrims as Catholic, distinct from their contemporary Christians who had abandoned such activities. While the pilgrimage asserted a Catholic claim to Scottish history, it also constructed an identity for modern Catholics around the nostalgic longing for an irretrievable past.

While this pilgrimage – and a similar revived cult of St Margaret at Dunfermline – contributed to the creation of a modern Scottish Catholic identity, it countered the identity of the Gaidhealtachd, the Gaelic Catholicism of the Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland that had persisted beyond the Reformation. When a 7m high statue of Our Lady of the Isles by Hew Lorimer was erected facing the Atlantic on the coast of South Uist, it was interpreted by the Catholic press and the hierarchy on one hand as marking a distinctively local phenomenon of fidelity to the Virgin and, on the other, as demonstrating Gaelic Catholicism’s continued allegiance to Rome through orthodox devotional practices. Indeed its inauguration on the feast of the Assumption in 1958 linked it to the centenary of Lourdes, celebrated throughout the world.12 Devotion to St Ninian, on the other hand, constructed a less controversial image of a modern Scottish Catholicism of ancient national origin, allied to prevailing Protestant narratives of Christianity though celebrated in a specifically Catholic manner.

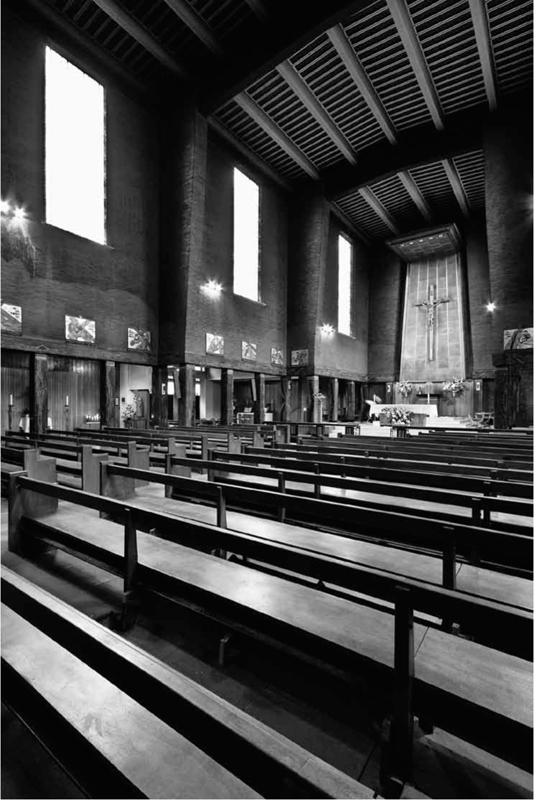

9.3 Tyburn Convent, London, by F. G. Broadbent & Partners, 1960–63. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

While some pilgrimages bridged the Reformation to evoke medieval Christianity, others sought to celebrate a national Catholic identity as one of defiance and martyrdom by remembering the Reformation itself. The Forty Martyrs of England and Wales, executed for their faith in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, became particularly important from 1960 when the bishops of England and Wales decided to press for their canonisation, finally achieved in 1970 under Paul VI. Since canonisation required evidence of miracles, campaigns of prayers and events were organised, including pilgrimages to associated sites.13 One was an annual pilgrimage in honour of the martyrs in central London. A procession began at the Old Bailey court, the site of Newgate prison where many of the martyrs were held, and traced their journey to martyrdom at Tyburn. The landscape of London had irredeemably changed: not only had Newgate disappeared, but Tyburn itself was merely a road junction. This pilgrimage nostalgically reimagined the contemporary environment, inscribing it through ritual with a hidden historical form, sacralising the banal and secular city and claiming it for a Catholic identity.

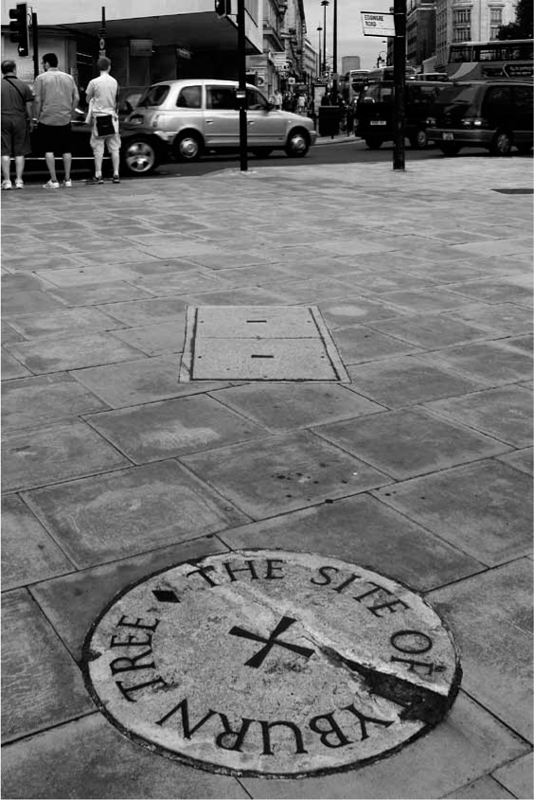

9.4 Plaque at Marble Arch, London, commemorating the site of the Tyburn gallows, laid in 1964. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

Since 1903, part of a Regency terrace on Bayswater Road had been occupied by a convent of French nuns and named after Tyburn.14 Bombed during the war, it was planned to rebuild it in the 1950s as a ‘national shrine’ to over 100 Tyburn martyrs, every diocese in England and Wales claiming at least one of the martyrs as their own. It was speculated that ancient trees in the convent garden might have been used as gibbets, giving them the status of relics, and the foundation stone of the new church, laid in 1961 by Cardinal Godfrey, contained a piece of stone from one of the martyrs’ prisons in the Tower of London.15 The new building was designed by F. G. Broadbent & Partners (Figure 9.3). On the ground floor below the convent chapel was a shrine chapel for pilgrims and visitors containing a life-sized replica of the triangular Tyburn gallows placed as a ciborium over the altar, and reliquaries of the martyrs lined its walls.16 Outside, a balcony became the focus of pilgrimage devotions: it was used at the culmination of the procession for a sermon and for Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament to the crowds who gathered in the street below.17 In 1964, on the traffic island nearby at Marble Arch, assumed to be the site of the Tyburn executions, a stone marker was laid in the pavement, a cross in its centre asserting its religious significance, instantly readable to British Catholics as a place made sacred by the blood of martyrs, consecrating a sacred place in the secular urban landscape (Figure 9.4).

The campaign of fundraising for the shrine created a sense of national Catholic community, including spectacular pageants performed at football stadiums throughout the country and widespread devotions to support the cause of canonisation. Many churches were dedicated to one or all of the Forty Martyrs. At St Thomas More, Knebworth, for example, Broadbent designed another Tyburn gallows as a ciborium over an altar that represented the block on which its patron saint was beheaded, bringing an element of the London shrine to this village church.18 The cult of the Reformation martyrs celebrated the rupture between the nation and Roman Catholicism, identifying Catholics in Britain with the persecuted saints. The Tyburn pilgrimage could also be adapted to a shared identification with other persecuted Catholics: in 1957, a silent march of 15,000 men from Hyde Park, next to Tyburn, to Westminster Cathedral protested against religious intolerance in eastern Europe, particularly Poland and Hungary, with many exiles taking part in the event. The Tablet reported:

Here, within sight of the spot where so many English martyrs died for the Faith in an earlier century, was being actualised our need to identify ourselves with those members of Our Lord’s Mystical Body who are suffering and dying for the Faith now, in the twentieth century, in other parts of the world.19

NATIONAL IDENTITY

In these cases of the ritual re-telling of history to assert combined national and religious identities for England and Wales and Scotland, few if any commentators ever mentioned the fact that the majority of Catholics in Britain were of Irish ancestry. The shrines at Aylesford and Cardigan owed their success to the efforts of Irish clergy, yet the new pilgrimage landscape promoted native Catholic identities. This apparent contradiction was also sometimes present in parish church architecture.

The strength of Roman Catholicism in Britain by the twentieth century was largely a result of Irish immigration in the nineteenth century, when Ireland had been part of Britain. Throughout the twentieth century, continued immigration ensured that a significant proportion of Catholics in Britain maintained Irish allegiances and a sense of national identity. Parish churches could often become a site for the construction and display of Irish communities. The Church in Britain, however, particularly at the level of the diocese, preferred instead to emphasise its Britishness. The two movements generally coexisted but occasionally came to confrontation. Post-war immigration from other Catholic countries, particularly Poland and Italy, could lead to even greater complexity in the church’s role as a focus for national identities.20

Irish immigration peaked in the mid-twentieth century, becoming increasingly diffuse as new industries and transport attracted migrants to London, Birmingham and Cardiff and to industrial towns such as Coventry and Luton in addition to former strongholds such as Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow.21 With Irish workers came Irish priests, recruited by British dioceses to compensate for a shortage of clergy in Britain and to cater for their countrymen: in the diocese of Birmingham in the mid-1950s, every parish had at least one Irish priest; in Leeds two-thirds of the clergy were Irish.22 Even as Irish identities amongst the descendants of earlier migrants abated, new arrivals sought to sustain a distinctive national culture.

Part of that culture was, for most, an adherence to Roman Catholicism, and the Catholic church was often the hub of immigrants’ social lives. Rex and Moore described the Catholic church in Birmingham as ‘the biggest Irish immigrant organization of all’ alongside lesser urban landmarks such as pubs and cafes. Secular social centres were incorporated into church sites: parish halls often had Irish bars and held Irish-themed events as fundraising ventures, often to fund a church building. Weekly attendance for Mass not only enabled the enactment of a ritual duty exactly as fulfilled in Ireland, but was also a social event.23 Family rituals such as weddings or funerals further reinforced Irish identity through the extensive kinship networks that became visible at these events. In and around and through the church building, the Irish reproduced and performed their identity.24

Church buildings were often given signs of Irish identity. A church’s dedication could celebrate a national saint and would be accompanied by an appropriate image. Many churches across Britain were dedicated to St Patrick in the post-war period – at Walsall, Coventry, Leicester, St Helens, Rochdale and many other places. St Finbar, seventh-century bishop of Cork, was commemorated with a parish in Liverpool. Dedications gave a familiar mark to a parish, extending to secular activities such as clubs and bars, sports teams and schools, where they became public bearers of a Catholic, and often a specifically Irish, identity. They were also associated with cult devotional practices that enabled the continued fulfilment of an aspect of national identity. In Ireland, the Sacred Heart had an especially strong following: a picture would be placed in the house over the fireplace, and the parish priest would dedicate the family to Christ, signing a document of consecration and attaching it to the wall with the picture, where a lamp would be kept constantly lit.25 The Sacred Heart shrine within a church evoked the memory of this family consecration, acting as a site of nostalgic evocation of home. Marian imagery was also prevalent in the home as well as the church in Ireland.26 The Catholic church building in Britain provided for the Irish immigrant a space with familiar resonances in the unfamiliar city.

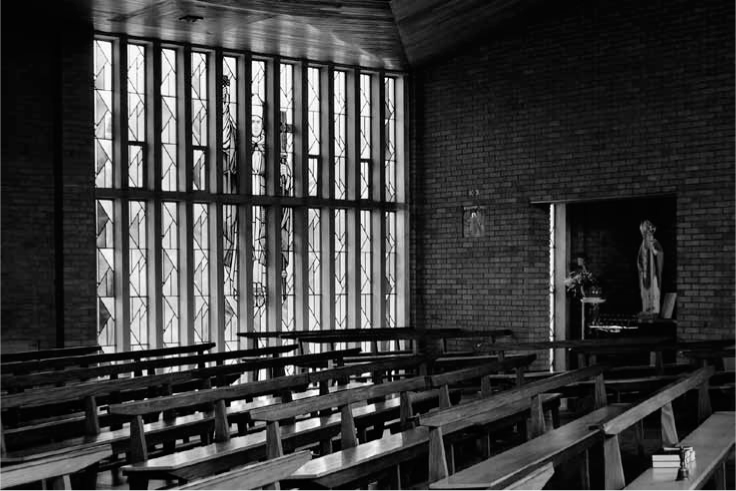

Shrines to St Patrick were also common in post-war Catholic churches in Britain, endorsing devotion to the national saint. They were often positioned near the door – a position of lower status than the saints associated with Christ, but significant perhaps in that the figure of Patrick was seen on entering and leaving the church, a reminder of identity for the Irish faithful at the point where the familiar space of religious custom met the secular and foreign world. At Adrian Gilbert Scott’s church of Sts Mary and Joseph in Poplar, for instance, a statue of St Patrick was placed on a permanent pedestal near the door (Figure 9.5); and in a more modern interpretation, the church of St Patrick in Coventry designed by Desmond Williams around 1967 included a stained-glass panel of the saint lit with electric light and placed in the vestibule (Figure 9.6). Both were parishes with especially high concentrations of Irish immigrants.

9.5 Sts Mary and Joseph, Poplar, London, by Adrian Gilbert Scott, 1951–54. Statue of St Patrick; one of the Stations of the Cross by Peter Watts is also visible. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

Decorative building materials could also indicate Irishness: one of the most popular, frequently employed for altars and other liturgical furnishings, was ‘Connemara marble’, dark green in colour. At D. Plaskett Marshall’s church of the Sacred Heart in Camberwell, London, of around 1958, the high altar and communion rails were of ‘Irish marble’, and the brick piers of this otherwise austere church were later clad in the material (Figure 9.7).27 Grey-veined Kilkenny marble was also frequently used, at Lionel Prichard’s St Agnes, Huyton of 1965, for instance, where altar, font and holy water stoups were all carved from it.28 Such materials would be proudly listed in opening brochures and newspaper reports for the benefit of parishioners. Sometimes they were specifically requested by the parish priest. At Yeading, the diocese of Westminster hesitated to approve a design for a marble altar and baldachino after finding that the priest had drawn it without the architect Justin Alleyn’s knowledge. The priest, Edward (or Eamon) Scanlan, was an Irish immigrant himself and had previously ministered in parishes with large numbers of Irish residents, at Somers Town and Southall.29 No doubt at his request, Alleyn incorporated broad panels of Irish marble into his otherwise modern design, as reredos-like backdrops for the high altar and Lady chapel (Figure 9.8).30 Marble, however, could also suggest an Italian source, and indeed Italian marble was also often used: St Louis in Brighton of 1965, for example, had an altar described as of ‘green Italian marble with insets of Irish Kellymount’.31 Thus a dual allegiance, to Ireland and to the universal church centred on Rome, could be declared through the fabric of the building at its most sacred points.

9.6 St Patrick, Coventry, by Desmond Williams, 1967–71. Stained glass depicting St Patrick in the vestibule, artist unknown. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church in England, Wales and Scotland, while attentive to the desires of its many Irish faithful, did not want the Church to be seen as Irish.32 Many dedications emphasised connections between Ireland and Britain: St Aidan, for example, a seventh-century Irish missionary who founded the monastery at Lindisfarne as part of the conversion of England to Christianity, was commemorated and celebrated with an external statue at the church at East Acton, an area with strong Irish as well as Polish and Italian communities. Fourmaintraux’s stained-glass panels in the sanctuary, meanwhile, depicted saints associated with English Christianity: on one side were St Mellitus, a missionary from Rome; St Thomas of Canterbury; St Hilda; St Edmund and St Erconwald, an Anglo Saxon bishop of London; facing them were Reformation martyrs (including, however, Oliver Plunkett, an Irish martyr who died at Tyburn) (Plate 5). The iconography of the church illustrated a predominantly native English Christianity with connections to Ireland.

Sts Mary and Joseph at Poplar similarly positioned Ireland within a political scheme emphasising Britishness. Most of its parishioners were Irish, employed at the nearby docks. Despite the church’s octagonal plan, its arrangement followed the familiar pattern, with the traditional layout of shrines, those for the Virgin and St Joseph being most prominent; the Sacred Heart was represented by a window in the sanctuary as well as a statue. St Patrick was depicted not only with a statue but also in a stained-glass window at the base of one of the four piers, but the other three pier windows contained images of Sts Andrew, George and David (Figure 9.9). The building therefore represented Ireland as if it was part of Britain, on an equal footing with the latter’s component countries; St George, however, was placed adjacent to the sanctuary, in the position of highest status. The upper-level windows depicted Sts John Fisher, Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas More and Edward: all English martyrs. Further groups of saints in the transept windows included St Augustine, early Christian missionary to England, flanked by St Gregory, the pope who sent him, and the English St Edmund; Roman saints such as St Peter were also present, articulating the ultimate authority of the Church. The iconography of this church was also a symbolic geography: while Irish visitors were permitted to feel a connection to their home, they were simultaneously reoriented towards an English and British identity.

9.7 Sacred Heart, Camberwell, London, by D. Plaskett Marshall, 1959. Connemara marble cladding added to piers later. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

9.8 St Raphael, Yeading, London, by Justin Alleyn, 1961. Reredos of Connemara marble; Lady chapel and Sacred Heart chapel also showing use of marble; dalle de verre windows by Pierre Fourmaintraux of Whitefriars Studios. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

Since so many clergy were Irish, tensions between the parish and the diocese could be played out in church buildings. Such a conflict arose at St Joseph, Wolverhampton, designed by Jennings, Homer & Lynch around 1965, partly serving a nearby Irish workers’ hostel.33 The parish priest by then was a Father Connolly, ‘whose political views’, complained the auxiliary bishop, ‘have alienated a number of people’, suggesting he supported Irish Republicanism.34 Connemara marble was used liberally throughout the church, including for the altar (Figure 9.10). Though officially dedicated to St Joseph, the church’s foundation stone attributes its patronage to Sts Joseph and Patrick, the latter name seemingly added without diocesan approval. A statue of St Joseph with rough carving and carpenter’s tools depicted St Joseph the Worker, a cult devotion created by Pius XII in the mid-1950s to counter European communism while mimicking some of its forms. In this context, the figure strongly suggests a sympathy with the socialist claims of the Irish nationalist movement at this period. Across the rear of the nave, stained-glass panels depicted St Joseph on one side and St Patrick on the other triumphantly raising a clover leaf (Figure 9.11). In his preface to the booklet accompanying the opening ceremony, Connolly declared a ‘CEAD MILE FAILTE to our Archbishop’, and praised glassmakers Hardmans for following his instructions.35 The depictions of these two saints at Wolverhampton promoted a highly politicised Irishness compared to the subdued forms of other churches. Connolly’s attitude, however, was unwelcome not only to the hierarchy but also to many of his parishioners, and it was an exceptional case.36 The prevailing model was one of coexistent narratives of identity, Irishness displayed in parallel with a Catholic Britishness.

9.9 Sts Mary and Joseph, Poplar, London, by Adrian Gilbert Scott, 1951–55. Stained glass by William Wilson. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

Besides the Irish, there were significant congregations of Catholics from other countries in Britain. Poles were the largest group, many having arrived in Britain during the Second World War. Their contribution to church art and architecture was substantial. The Liverpool firm of Weightman & Bullen recruited some from amongst the Polish architecture students who had arrived at Liverpool University during the war, forming a Polish School of Architecture, notably Stanislaus Pater-Lancucki (known as Stan Pater) and Jerzy Faczynski.37 Adam Kossowski, the ceramicist, had been a notable artist in Poland before the war, teaching at the Warsaw Academy of Art. He arrived in London in 1943 after being released from a Russian prison camp the year before.38 Many of Greenhalgh & Williams’s churches after 1960 were designed by Tadeusz Lesisz, who had been a lieutenant in the Polish navy when it defected to Britain in 1939. He remained after service to train as an architect at the Oxford School of Architecture, his three brothers having been murdered in Dachau and Katyn.39 Altogether 160,000 Poles stayed in Britain after the war, and, by 1960, there were about 100 Polish priests with their own parallel hierarchy and parish structure in England and Wales established with the help of Cardinal Griffin in 1948. The Polish Catholic Mission began in 1947 to provide for the religious and social needs of exiles and to sustain a particular vision of Polish national identity, one of its primary functions being the provision of church buildings.40

9.10 St Joseph, Wolverhampton, by Jennings, Homer & Lynch, 1967. Connemara marble in the sanctuary on the wall behind the altar and for the altar and communion rails; stained glass of Sts Peter and Paul by Hardman & Co. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

9.11 St Joseph, Wolverhampton, by Jennings, Homer & Lynch, 1967. View to rear of church: stained glass of St Patrick by Hardman & Co. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

One of Lesisz’s first commissions as an architect was for the Polish Church of Divine Mercy in Manchester around 1958. Named after the twentieth-century apparitions of Christ as the Divine Mercy to a Polish nun and the subsequent shrine in Krakow, this church served the Polish community throughout Manchester. It began with the purchase of a Victorian Presbyterian chapel, undoubtedly for reasons of economy but also effectively concealing the presence of a Polish congregation from the outside. The same approach was taken in other cities, most importantly in London, where a former Presbyterian chapel in Shepherd’s Bush was bought and converted for use as the Polish church of St Anthony Bobola.41 Inside, however, these churches were redesigned to evoke a Polish identity tied to Catholicism.42 St Anthony Bobola in London became a repository of Polish national symbols, architect Aleksander Klecki and artist Tadeusz Zielinski working on alterations and new features continuously from 1961 (Figure 9.12). A basement was excavated to create a Polish social centre and café. Above, a new aisle was added with a chapel to contain a celebrated relief of the Virgin, Our Lady of Victories of Kozielsk, named after the town that became a Russian prison camp where it was secretly made by Polish prisoners; the image was accorded sacred status as a symbol of hope for return to Poland after exile. The church was further enhanced with sculpture and artworks. Stained-glass windows commemorated Polish military organisations, and there was a prominent memorial to the dead of the massacre at Katyn. The interior was a setting for ceremonies with a national focus, gathering the Polish community in London for events associated with the Polish government in exile and the military, as well as being a centre of Polish social activity.43 The church created an image of Polish identity in relation to wartime experiences, becoming essentially a multi-faceted war memorial. The exterior of the church was undemonstratively adorned with a modern sculptural panel of angled crosses, hinting at this extraordinary role.

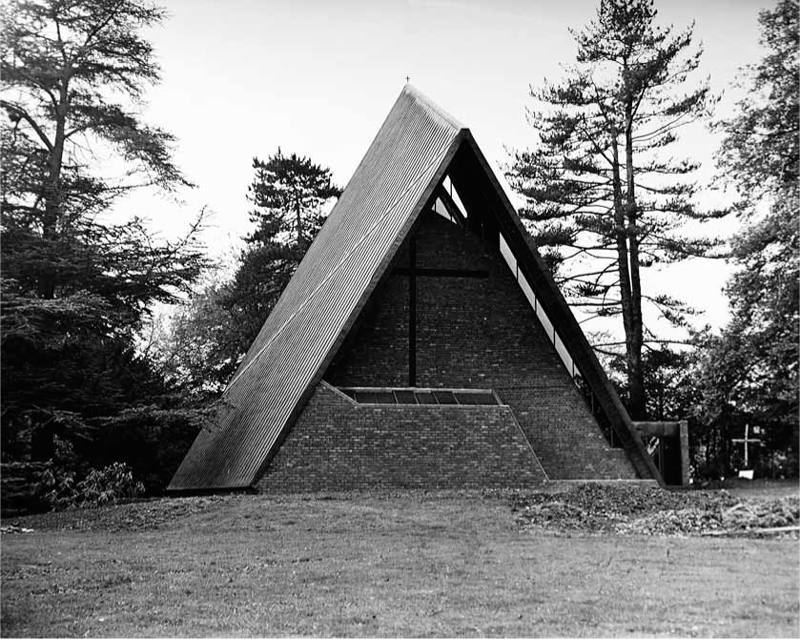

Another Polish architect, George Wladyslaw Jarosz, arrived in Britain after being released from a Nazi prison camp and completed his studies at the Polish School of Architecture, after its relocation from Liverpool to London in 1947, subsequently joining the office of notable modernist architect William Crabtree.44 Jarosz was invited to design the chapel of St Ann at Fawley Court in Buckinghamshire, where a seventeenth-century house had been converted into a school for Polish boys in 1952 by the Congregation of Marian Fathers, a Polish order, under the patronage of exiled Prince Stanislaw Radziwill. The chapel was completed in 1973 for use by the school and the local community, but also served as a memorial to Radziwill’s mother Anna, Princess Lubomirska, who had died in 1947 in a Soviet labour camp. Jarosz’s design had no overtly Polish allegiances, and aimed rather to be sympathetic to its site in a Capability Brown landscape, following the influence of Scandinavian modernist churches the architect had seen, with a tall pitched roof, pine-boarded inside, perched over a brick podium (Figure 9.13).45 Devotional objects and memorial panels, however, formed focal points with national resonances, including a shrine to Christ of the Divine Mercy and the tomb of Radziwill himself, placed in the crypt after his death in 1976 and guarded by gates containing bronze panels of the Polish eagle with the arms of the Radziwill family.46 An external altar allowed for outdoor services for liturgical events involving large-scale gatherings of British Poles. Outside the normal systems of patronage for churches, and indeed outside the city, and therefore in something of a liminal space, this church became one of the most important focal points for Polish exile identity in Britain, a site where its community was created and defined. In 1964, for example, celebrating the millennium of the Polish Christian monarchy and the nation, 7,000 Poles attended a service at Fawley Court. Many wore national dress, and the Mass was followed by traditional songs and dances.47

9.12 St Anthony Bobola Polish Church, London, 1961 onwards, alterations by Aleksander Klecki. Sculpture and stained glass by Aleksander Klecki. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2013

In London two cases stand out as being special types of national church, where the home nation’s involvement in their creation made them showcases of their respective religious cultures. Notre Dame de France near Leicester Square had been built in the nineteenth century by Parisian architect Louis-Auguste Boileau, circular in plan because of its site on a former panorama. Hector Corfiato of the Bartlett School of Architecture rebuilt it in 1955 following war damage, maintaining the circular plan and much influenced by modern French architecture (Figure 9.14). The selection of the architect and the organisation of a scheme of artworks was entrusted by the church’s priest, Francisque Deguerry, to the French embassy’s cultural advisor, René Varin, who used the church to demonstrate contemporary French religious art. Corfiato himself was an alumnus of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. External sculpture was commssioned from distinguished French sculptor Georges Saupique, who had previously worked on churches in France. French decorative arts techniques were demonstrated by a ceramic font and by an Aubusson tapestry depicting a figure of the Virgin by French Benedictine Robert de Chaunac, known as Dom Robert, hung behind the altar. The most daring and original work, however, was commissioned from Jean Cocteau, who in 1960 added a striking figurative fresco to the Lady chapel and its altar.48 Varin must have been aware of the Art Sacré movement, and Cocteau’s commission in London was an act of patronage that brought a taste of this movement to Britain, claiming it as a French national project. Meanwhile the German Catholic church of St Boniface at Stepney was also destroyed by German bombs and was rebuilt with the patronage of the West German government and Catholic hierarchy in 1960 by local Catholic architect D. Plaskett Marshall. German artists Heribert Reul and Gunther Reul created a sgraffito artwork behind the altar depicting Christ and St Boniface, the English Christian missionary to Germany.49

9.13 Church of St Anne, Fawley Court, Buckinghamshire, by Crabtree & Jarosz, 1973. Photographer unknown. Source: archive of George W. T. Jarosz, London

9.14 Notre Dame de France, London, by Hector O. Corfiato, 1955. Tapestry by Dom Robert, Tabard Workshop, Aubusson, 1955; chapel with fresco by Jean Cocteau of 1960 visible in the centre of the photograph; fresco © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London, 2013. By permission of the Rector and Trustees of Notre Dame de France. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

PARISH COMMUNITIES

National identities, however, were only one amongst several kinds of identity that could be performed in parallel by Catholics in Britain: the construction of local parish and city communities through the church building and associated rituals also contributed to a sense of belonging and a sense of place within the nation. The construction of a parish church itself served as a means of building a parish community through the performance of a shared identity amongst its members. Despite their administrative dependence on the diocese, in theory Roman Catholic parishes had to be financially independent and self-sufficient. Building a church therefore demanded huge efforts at fundraising within the parish. Since most churches were built through bank loans, the debts incurred by parishes required extensive fundraising long after their buildings were completed. While Roman Catholic churches could be dedicated and used as soon as they were finished, they were not permitted to be formally consecrated until the debt had been paid. Achieving the status of a consecrated church was a landmark in the history of every parish, the result of a collaborative project involving virtually every active parishioner, bringing them together in work and entertainment for the benefit of the Church.

Fundraising brought parishioners together in a common aim. While the parish priest and his curates organised much of the work themselves, some parish affairs were delegated to parishioners: parish priest Patrick Waldron of St Francis de Sales, Hampton Hill, in London created numerous lay committees, including a Finance Committee, Entertainments Committee, Liturgy Committee and an Art and Maintenance Committee, all with a role to play in achieving their new church building.50 A church was the ‘dream’ of every parish from its inception, often described as such in parish histories, and it was the product of the whole parish, a manifestation of the parish’s social life and a representation of its community. Buildings would often commemorate this community aspect of their production. Sometimes a ‘golden book’ containing a list of donors would be kept in the church: at the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Hayes, opened in 1961, one such book was kept in a chapel under a plaque listing all the priests who had served in the parish.51 Donations from parishioners towards schemes of furnishing and decoration could also be rewarded by associating donors’ names with objects in the church.

One of the most assiduous of such campaigns took place at St Mary at Failsworth in Manchester, where parishioners collaborated in offering items for the church, listed in the booklet accompanying the church’s dedication. The parish branch of the Union of Catholic Mothers paid for the baptistery, and the font was donated by over 70 ‘ladies of the parish’, including the ‘infant teachers’. The Stations of the Cross were donated by families and painted by a parishioner. Past parishioners were approached to fund the Lady chapel, including those in America and Ireland; its tabernacle and statue were donated, and each panel of its stained glass windows was ascribed to a family. The communion rails were donated by the men’s club. Funds for the sanctuary furnishings were raised by the infants’ school. The pulpit, side chapels, altar linen, sanctuary lamp, Missal and candlesticks were all attributed to donors. The mosaic reredos was donated by the parish priest in memory of his parents, who had also been parishioners at Failsworth.52 This associating of objects in the church with donors was met by overwhelming generosity, as many of the faithful wished to be publicly identified as members of the corporate body of the parish through the embellishment of the church.

The opening or consecration of a church was frequently an occasion for setting out the history of the parish, celebrating the communal achievement of its members, and helping to consolidate the notion of the parish as a social unit. The struggles of parishioners as they forged a Catholic society were vividly described, the new church building represented as the culmination of their efforts. Earlier buildings marked phases in the parish’s growth. The souvenir booklet of St Columba, Bolton, celebrating its combined opening and consecration of 1956, is typical. Before 1931, the residents of the new housing estate at Tonge Moor walked miles to their nearest church. Some land was bought closer to the estate, intended for a chapel-of-ease; then, in 1931, the diocese created a new parish, and a priest arrived: ‘What a task confronted him! All he had was a field’. Mass was said at the cricket club until a temporary church could be built ‘at a cost of £800’. ‘The parishioners pulled together and Father O’Dwyer laboured on’. His successor built a new junior and infants’ school within months of arriving in 1937. A presbytery followed, its cost meticulously documented. ‘With the wholehearted co-operation of the faithful and friends the seemingly impossible was accomplished. The parish was free of debt 20th December, 1942.’ Immediately fundraising for a new church began. An architect was chosen: Geoffrey Williams was a parishioner of St Columba and waived his fee. The foundation stone was laid in a ceremony of 1955. As the building rose, parishioners inspected it every week after Sunday Mass: a photograph in the booklet records the construction site. ‘At a meeting of the men of the parish, one Sunday morning early in 1956, the one and only topic of discussion was our new church – would it be opened by Christmas to celebrate the Silver Jubilee of the first Mass in the “old” church?’ The priest assured them it would. And there was more delight: the possibility that the debt would be paid before it was complete, and the church could be consecrated.53 The consecration and opening ceremonies followed, and the souvenir booklet concludes with a description and photograph of the completed building. This document gives an impression of a parish literally and metaphorically building itself through saving and work.

It is significant that fundraising was motivated by the parish’s history, ensuring that St Columba’s new church was opened on the anniversary of the old. In many church buildings the parish’s history would be literally incorporated into the architecture by integrating a relic from the past. At John Rochford’s church of St Paul at Wood Green, the previous church by Edward Goldie of 1904 was demolished, but its stained-glass windows were kept and inserted into a specially designed entrance corridor (Figure 9.15).54 At their new church of St Catherine, Horsefair in Birmingham, Harrison & Cox incorporated stained-glass windows from the Victorian church that had been demolished by order of the city. At St Peter-in-Chains, Doncaster, the Victorian church’s high altar and reredos, designed by a member of the Pugin family, were rebuilt as a Blessed Sacrament chapel in Langtry-Langton’s much larger church of 1973. The replacement of a parish church was a trauma, eased by incorporating its fragments within the new church to symbolise the unity of a parish over time.

Ritual celebrations surrounding new buildings were occasions for symbolic enactments of the Catholic parish in its relationships to both the broader Church and to the secular world. The laying of the foundation stone, the dedication and opening ceremony and the consecration, often decades later, were ceremonies normally performed by the bishop, and were often spectacular displays of the local or national hierarchy. The entire parish would participate, often in public processions, encompassing the grounds of the church, extending through surrounding streets, and in some cases accompanying the transfer of the Blessed Sacrament from its previous location to the tabernacle of the new church. The opening of St Mary, Leyland, in 1964 was one of the most dazzling events of this kind: the procession went through the town from the old church in the centre to the new building a mile away (Figure 9.16). The clergy, including the celebrant Bishop Parker of Northampton (whose brother had been a priest at Leyland), Bishop Beck of Liverpool and the monks of the friary, accompanied by the servers, all in their most splendid vestments, followed 2,000 parishioners, divided into ranks according to their membership of parish institutions. Mothers pushing infants in prams formed one cohort, representing the Union of Catholic Mothers; men formed another; boys and white-dressed girls from the schools and older women in old-fashioned hats made up further groups. Also in attendance was a large delegation from Ampleforth, including its abbot, Basil Hume. The local Member of Parliament and town councillors were invited, showing the parish’s relationship to its civic community.55 A brass band accompanied the procession. Crowds of non-Catholic onlookers lined the streets as spectators. The parish performed and effected community through such a display of unity in public view.

9.15 St Paul, Wood Green, London, by John Rochford, 1965–72. Vestibule passageway containing stained glass from former church of 1904. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

In several cities, particularly in Lancashire, further public rituals defined Catholics specifically in terms of their civic identity. The Manchester Whit Walk was an event that developed during the mid-nineteenth century as a city-wide ceremony. The week following Whitsun was a holiday in Manchester and its surrounding towns, for which the churches organised religious spectacles. On Monday, the children of all Anglican parishes in the city walked from their churches to the city centre, converging on Albert Square in front of the Town Hall. On Friday, it was the turn of Catholics, who did the same. The boys of each parish wore school uniforms, and the girls wore white dresses and carried lilies; they also held banners bearing the names of their churches. Parish groups also joined in, and each parish had its own band. The procession was most famous for the lavish displays staged by the Italian church at Ancoats: the men walked in procession carrying the church’s crucifix and the flower-bedecked statue of the Virgin Mary borrowed from the Lady chapel. Polish and Ukrainian Catholics also participated as distinct groups, many in national dress. The procession filed past the bishop of Salford for over three hours before assembling in Albert Square. In 1949, it was estimated that 20,000 joined in the walk, revived then for the first time after the war.56

This ritual presented Roman Catholics to themselves and their neighbours in the context of the city as a civic group rather than as a diocesan or parochial one. Nevertheless it showed the city’s Catholics in terms of their parishes. Italians and Poles defined themselves as Catholics through their participation, while celebrating their distinctive identities as settlers in the city.57 A similar event took place in Bolton, but, in 1968, after several experiences of poor weather, there was doubt over its future. Bishop Thomas Holland of Salford noted arguments for its discontinuation, including suggestions that developments in Christian unity might be hindered by displays of Catholic rivalry with other denominations. It was also important to consider the increasing secularisation of society and its preference for confining the sacred to a separate sphere. Against such claims, however, he insisted the event proceed: the procession was important as a ‘public witness to our Faith’. ‘We strengthen the ties which link us to our parish and the parishes to one another’, he argued, and ‘we enrich the life of our city’.58 Through this ritual the streets of the city became a sacred space, activated by a spectacular processional movement that enacted relationships between Catholics, their institutions and the city. A Catholic geography of the city was articulated through the convergence of parishes, united at the central point where the city’s corporate identity was embodied. In asserting their ‘right to the city’ by claiming public space for religion, Roman Catholics demonstrated their presence in civic society and brought their communities into being.59

9.16 St Mary, Leyland. Procession at opening ceremony, 1964. Photo: Tony Hart, 1964. Source: parish archive

NOTES

1 Turner and Turner, Image and Pilgrimage, 63–93, 106–35.

2 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991), 145; see also for example Judith Butler, ‘Performative Acts and Gender Constitution’, in Michael Huxley and Noel Witts (eds), The Twentieth-Century Performance Reader (London: Routledge, 2002), 120–34.

3 The theoretical framework for this chapter derives from several sources: Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. Karen E. Fields (New York: Free Press, 1995); summarised by Catherine Bell, Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 24–5; David Parkin, ‘Ritual as Spatial Direction and Bodily Division’, in Daniel de Coppet (ed.), Understanding Rituals (London: Routledge, 1992), 11–25; Roy A. Rappaport, ‘Enactments of Meaning’, in Michael Lambek (ed.), A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion (Oxford: Blackwell, 2008), 410–28; Andrew Parker and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, ‘Introduction’, to eid. (eds), Performativity and Performance (London: Routledge, 1995), 1–18.

4 ‘Pontifical Mass in Scots Cave’, Catholic Herald (25 Sept. 1953), 1; ‘Whithorn Pilgrimage’, St Andrew Annual: The Catholic Church in Scotland (1960–61), 93.

5 J. Stopford, ‘Some Approaches to the Archaeology of Christian Pilgrimage’, World Archaeology 26 (1994), 57–72 (60–61); Francis Hindes Groome (ed.), Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Survey of Scottish Topography, Statistical, Biographical and Historical, vol. 6 (Edinburgh: T. C. Jack, 1882–85), 484–6.

6 David Stuart to William Mellon (bishop of Galloway) (27 Sept. 1951) (SCA, DG/54/2).

7 Basil Spence to Joseph McGee (bishop of Galloway) (5 Feb. 1954) (SCA, DG/54/2).

8 Design drawings and photographs of model (Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland, Edinburgh, Spence, Glover and Ferguson Collection, SGF 1950/66/1, SGF 1950/42/1/8); see also Clive Fenton and David Walker, ‘The Modern Church’, in Louise Campbell, Miles Glendinning and Jane Thomas (eds), Basil Spence: Buildings & Projects (London: RIBA Publishing, 2012), 104.

9 McGee, circular letter to diocesan clergy (3 Feb. 1956) (SCA, DG/54/3).

10 McGee, circular letter to diocesan clergy (3 Feb. 1956) (SCA, DG/54/3).

11 H. S. Goodhart-Rendel to McGee (21 Dec. 1955) (SCA, DG/54/2).

12 Ray Burnett, ‘“The Long Nineteenth Century”: Scotland’s Catholic Gaidhealtachd’, in Raymond Boyle and Peter Lynch (ed.), Out of the Ghetto? The Catholic Community in Modern Scotland (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1998), 179, 184.

13 ‘Joint Pastoral on 40 Martyrs’, Catholic Herald (1 July 1960), 1.

14 T. F. T. Baker, Diane K. Bolton and Patricia E. C. Croot, A History of the County of Middlesex, vol. 9: Hampstead, Paddington, ed. C. R. Elrington (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 259–60, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=22675 (accessed 6 Dec. 2012).

15 ‘Shrine Will Rise on Tyburn Ruins’, Catholic Herald (4 Jan. 1952), 1; ‘From Our Notebook’, The Tablet (25 Nov. 1961), 1127.

16 ‘From Our Notebook’, The Tablet (19 Mar. 1960), 273; ‘Tyburn’s New Shrine’, Catholic Herald (25 Mar. 1960), 1; ‘£25,000 Debt on Shrine’, Catholic Herald (29 May 1964), 1.

17 Advertisement, ‘Annual Tyburn Walk’, The Tablet (15 Apr. 1961), 367.

18 G. C. Davey, ‘A Tyburn Tree for Knebworth’, Catholic Herald (12 May 1961), 6; CBRS (1963), 49–53.

19 ‘From Our Notebook’, The Tablet (13 Apr. 1957), 355; see also ‘Exiles’ Candles Symbolises the Silent Church’, Catholic Herald (12 Apr. 1957), 1.

20 The framework for the analysis that follows is provided by Anne-Marie Fortier (Migrant Belongings: Memory, Space, Identity [Oxford: Berg, 2000]).

21 Enda Delaney, The Irish in Post-War Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 89–109; Jackson, The Irish in Britain, 11–19; see also Hornsby-Smith, ‘A Transformed Church’, 8–9.

22 Delaney, Irish in Post-War Britain, 145.

23 See Sharon Lambert, Irish Women in Lancashire, 1922–1960: Their Story (Lancaster: Centre for North-West Regional Studies, 2001), 63.

24 This section on Irish national identity is adapted from Robert Proctor, ‘Religion and Nation: The Architecture and Symbolism of Irish Identity in the Roman Catholic Church in Britain’, in Raymond Quek, Darren Deane and Sarah Butler (eds), Nationalism and Architecture (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2012), 39–51.

25 Lambert, Irish Women in Lancashire, 46.

26 On the similar role of devotions to the Virgin Mary, see Bronwen Walter, Outsiders Inside: Whiteness, Place and Irish Women (London: Routledge, 2001), 18.

27 CBRS (1958), 88.

28 CBRN (1965), 62–3.

29 ‘Obituaries: Valuable Participant at Vatican II’, Catholic Herald (8 Jan. 1993), 3; ‘Father’s Farewell’ [newspaper cutting] (c.1986) (parish archive, St Raphael, Yeading, London).

30 [Derek Worlock] (private secretary to William Godfrey, archbishop of Westminster) to B. Kent (assistant to finance secretary, diocese of Westminster) (30 June 1960) (WDA, Godfrey Papers, Go/2/132).

31 CBRS (1965), 88.

32 Hickman, Religion, Class and Identity, 12, 204, ch. 5.

33 Visitation Report (7 Feb. 1949) (ARCAB, Parish Files, P316/T5).

34 Joseph F. Cleary (auxiliary bishop), visitation report (1972) (ARCAB, Parish Files, P316/T5).

35 St Joseph, Wolverhampton, opening souvenir brochure (4 Dec. 1967) (ARCAB, uncatalogued).

36 Cleary, visitation report (1972) (ARCAB, Parish Files, P316/T5).

37 Patricia Brown and David John Brown, interview with Ambrose Gillick, York (3 Apr. 2012).

38 Martin Sankey, ‘An Interview with Adam Kossowski, 1978’, in Read et al., Adam Kossowski, 65–80.

39 Michael Dembinski, ‘Tadeusz Lesisz: Pole who Sailed with the Royal Navy and Saw Action on D-Day and in the Battle of the Atlantic’, The Independent (12 Oct. 2009), http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/tadeusz-lesisz-pole-who-sailed-with-the-royal-navy-and-saw-action-on-dday-and-in-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-1801365.html (accessed 2 Jan. 2013).

40 Nick Gill, ‘Pathologies of Migrant Place-Making: The Case of Polish Migrants to the UK’, Environment and Planning A 42 (2010), 1157–73 (1164).

41 Walker, ‘Developments in Catholic Churchbuilding’, 345.

42 CBRN (1959), 94–7; see also CBRN (1968), 79–81.

43 See Andrzej Suchcitz (ed.), Kronica Kościoła św. Andrzeja Boboli w Londynie, 1961–2011 (London: Polish Catholic Mission Hammersmith, 2012).

44 Wladyslaw Jarosz to Robert Proctor (13 Jan. 2013).

45 Wladyslaw Jarosz, interview with Robert Proctor, London (11 Feb. 2013).

46 ‘Church of St Anne, Fawley Court’ (28 Sept. 2009), English Heritage, http://list.english-heritage.org.uk/resultsingle.aspx?uid=1393459 (accessed 4 Jan. 2013).

47 ‘7,000 Poles Rally at Henley’, Catholic Herald (22 May 1964), 3.

48 D. Raabe, P. O’Reilly and G. Dumas, Notre Dame de France (London: n.p., 1965), 24.

49 For example ‘Destroyed – Rebuilt’, Catholic Herald (18 Nov. 1960), 5; ‘Sleek, Neat and Modern’, Catholic Herald (26 Aug. 1960), 7.

50 Ann Kimmel, ‘Go-Ahead Priest with Go-Ahead Parishioners’, Catholic Herald (16 Dec. 1966), 3.

51 ‘Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish, Hayes Middlesex’ [parish history] (n.d.), 14–15 (parish archive).

52 ‘St Mary’s, Failsworth: 1845–1964’ (parish archive).

53 ‘Souvenir to Commemorate the Consecration, 12th December, 1956 and Solemn Opening, 16th December 1956, of St Columba’s Church, Bolton’ (parish archive).

54 A. P. Baggs et al., A History of the County of Middlesex, vol. 5: Hendon, Kingsbury, Great Stanmore, Little Stanmore, Edmonton Enfield, Monken Hadley, South Mimms, Tottenham, ed. T. F. T. Baker and R. B. Pugh (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976), 355–6, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=26994 (accessed 31 Jan. 2013); CBRS (1970), 72–3.

55 ‘Mile Long Procession’, Catholic Pictorial [souvenir supplement] (12 Apr. 1964), 8; Leyland Guardian [souvenir supplement] (10 Apr. 1964) (parish archive, St Mary, Leyland).

56 ’20,000 Walk in Whit-Friday Procession’, Catholic Herald (17 June 1949), 7.

57 George Andrew [Beck], draft foreword to programme (16 Apr. 1962) (SDA, Building Office papers, 094).

58 Thomas [Holland], foreword to Bolton Annual Catholic Procession, 1968, Sunday, June 9th, Official Programme (archive of Thornleigh Salesian College chapel, Bolton).

59 See Tovi Fenster, ‘Non-Secular Cities? Visual and Sound Representations of the Religious-Secular Right to the City in Jerusalem’, in Justin Beaumont and Christopher Baker (ed.), Postsecular Cities: Space, Theory and Practice (London: Continuum, 2011), 69–86.